NAVAL AIR STATION LEMOORE, Calif. — From the air control tower at the center of the U.S. Navy’s largest jet base, the roar of fighter engines is inescapable.

It’s coming from the rows of F/A-18E/F Super Hornets — and, increasingly, F-35C Joint Strike Fighters — on the flight line, going through routine maintenance before hitting the skies.

It’s also coming from the runway, as jets speed by with chest-rattling force as they return from practicing flight formations over the surrounding farmland.

It’s a reassuring sound to Navy leaders — a sign the squadrons’ maintainers and the depot artisans at Fleet Readiness Center West are turning jets around so pilots can get back in the air for training and deployment preparations.

But as the service’s F-35C fleet expands here in Lemoore, both the Navy and a government oversight group worry the Joint Strike Fighters aren’t available for missions often enough. And to make matters worse for the fleet, it’s costing more than expected to sustain the aircraft.

The Joint Strike Fighter program stands in contrast to most other military aircraft programs: Lockheed Martin plays an outsized role in jet readiness, with the company responsible for maintenance planning and management, distribution of repair parts and supplies, engineering, maintenance training, and more. The government’s F-35 Joint Program Office, or JPO, oversees the global fleet of F-35 jets and manages the facilities and people that support maintenance.

This leaves the services with little control over ensuring their own readiness. But the Joint Strike Fighter Wing in Lemoore, which oversees all Navy F-35Cs, is taking extra steps to directly improve readiness by drawing lessons from the service’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornets.

In 2018, then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis ordered the military branches to hit an 80% mission-capable rate for all fighters in fiscal 2019. With Super Hornet mission-capable rates barely above 50% for much of 2008 through 2018, the Navy kicked off a data-driven effort to analyze its processes, facilities, supply practices and more, dubbed Naval Sustainment System-Aviation. By the end of FY19, the service surpassed 80% and has sustained that readiness since.

Now, the Joint Strike Fighter Wing is working with its F-18 counterparts to adopt proven practices on operation-level maintenance to boost readiness and lower costs. As part of this effort, the Navy is particularly bolstering its data collection and communication efforts.

Those efforts are yielding results: The Navy’s F-35C community has higher readiness rates and fewer aircraft awaiting supply parts than the rest of the global F-35 fleet’s average, a service leader told Defense News.

That improvement on readiness and cost matters, given the threat of a high-end fight in the Pacific and mushrooming procurement costs.

“From a budget standpoint, it is simple economics: The more it costs to buy and maintain aircraft, the fewer we can procure in a tight fiscal environment and the more onerous it will be to repair them,” Rep. Rob Wittman, R-Va., the vice chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, told Defense News.

“We also cannot go to war, especially against an adversary with advanced [anti-access/area-denial] capabilities, without our most advanced fifth-generation aircraft,” he added.

Slow repair times, lower aircraft readiness

In a September report, the Government Accountability Office detailed the failures in Joint Strike Fighter maintenance and availability of spare parts.

The watchdog’s report noted that in March 2023, 55% of planes were considered mission capable, meaning they were able to fly and conduct at least some warfighting missions. It attributed this low readiness to maintenance challenges at the squadron and depot levels.

The report detailed the unique maintenance setup: Other programs like the Navy’s Super Hornets are repaired through operational-level maintenance by squadrons, intermediate-level work by the Navy’s fleet readiness centers located at the jet bases, and depot-level work at select fleet readiness centers.

But the F-35 program does not include any intermediate-level maintenance; instead squadrons must undertake more work on the flight line with help from contractors, while farming out more work to industry at depot locations and at the original builder’s facilities.

In the case of the Super Hornet, the Navy controls all three levels of maintenance and signs its own contracts for support and parts. In contrast, the F-35 program gives significant responsibility to manufacturer Lockheed Martin and to the Joint Program Office, leaving the services with little ability to change or improve the supply system and contractor-led maintenance.

At the operational level, the GAO report noted, squadrons lack some technical data and training experience needed to efficiently conduct maintenance — a challenge that will only grow if the JPO decides to shift more work from industry to the services by adding intermediate-level maintenance to the plan.

At the depots, it noted the JPO is now 12 years behind schedule in standing up some of its repair capabilities, or “workloads.” As of last spring, 44 of 68 workloads were activated.

“Delays in standing up the F-35 program’s depot repair capacity has had several effects, including slow repair times, a growing backlog of components needing repair, and lower aircraft readiness,” the report found.

GAO projects the total fleet’s mission-capable rate could have been at 65% instead of 55% last spring if not for the lack of depot repair capacity.

The lack of depot capacity is also increasing the cost.

With the depots now facing a backlog of 10,000 components to repair, “the F-35 Joint Program Office has purchased new parts instead of repairing the parts it already has in inventory. According to [Department of Defense] officials, this is a practice that program officials do not believe is a sustainable solution.”

Those officials said the approach keeps the aircraft flying, but it results in “higher sustainment costs because buying new parts generally costs more than repairing existing parts.”

Hard-earned lessons from the F-18

In remote Lemoore — where fighter jet squadrons are based a six-hour drive from the admirals in San Diego and a six-hour flight from the JPO in Arlington, Virginia — the captains are in charge.

Joint Strike Fighter Wing Commodore Capt. Barrett Smith and Strike Fighter Wing Pacific Commodore Capt. Michael Stokes are part of a “council of captains” that work together to manage aircraft readiness, facilities, personnel and families at Lemoore.

Smith and Stokes leveraged this close collaboration to boost the Joint Strike Fighter Wing’s primary contribution to F-35C readiness: operational-level maintenance performed by each squadron.

Stokes said the Navy in 2018 brought in the Boston Consulting Group to make recommendations as part of the effort to get F-18s to an 80% mission-capable rate.

He said one of the most consequential results was the creation of the Maintenance Operations Center, which monitors aircraft status daily. The center uses that data to prioritize distribution of parts, provide technical assistance, and identify potential broader changes to boost readiness or reduce cost.

Smith said the F-35C joined the center in October 2022 as part of its own effort to boost the readiness of its planes.

This data can point to problems in real time — for example, a supply issue that’s holding up several planes in a single squadron that has a major exercise coming up — and can also reveal trends over time that might make a squadron reconsider its workflow or whether maintainers need additional training, Smith said.

Stokes said one seemingly simple change recommended by the Boston Consulting Group was to put a whiteboard by each aircraft undergoing maintenance in the squadron hangar or down the road at Fleet Readiness Center West. Each whiteboard would note “the lead person and all of the outstanding items so you can see it in front of that aircraft,” he said.

The two say these practices are yielding results.

On a Feb. 15 visit by Defense News, the Navy had 347 mission-capable Super Hornets, well above the Navy’s requirement to maintain a monthly average of 333.

(The Navy previously had a goal of 341 and then 360 mission-capable Super Hornets, to reflect Mattis’ 80% goal. The inventory of Super Hornets is smaller today, as some squadrons have transitioned to the F-35C. Stokes said the 333-plane goal still equates to an approximately 80% mission-capable rate.)

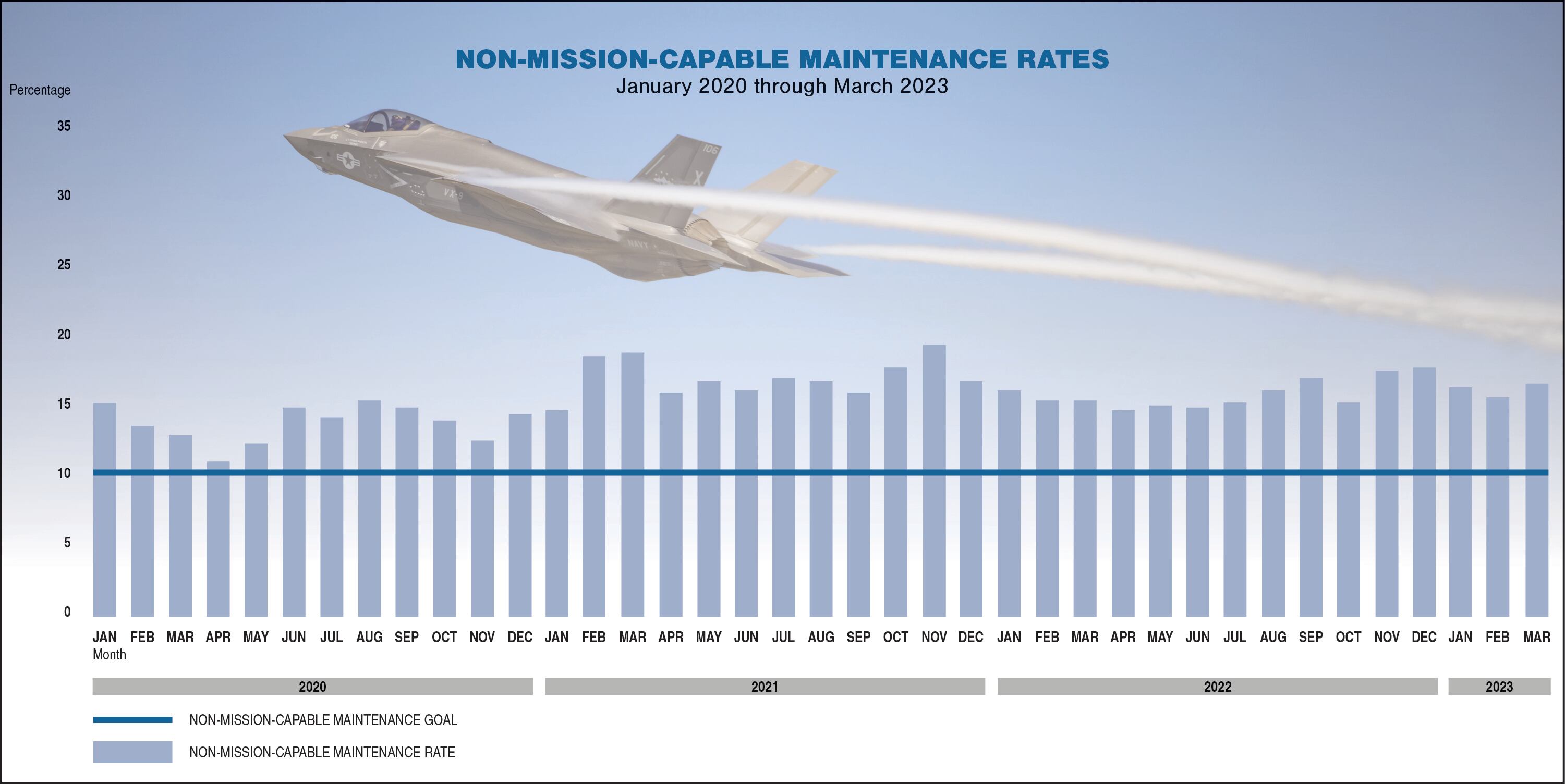

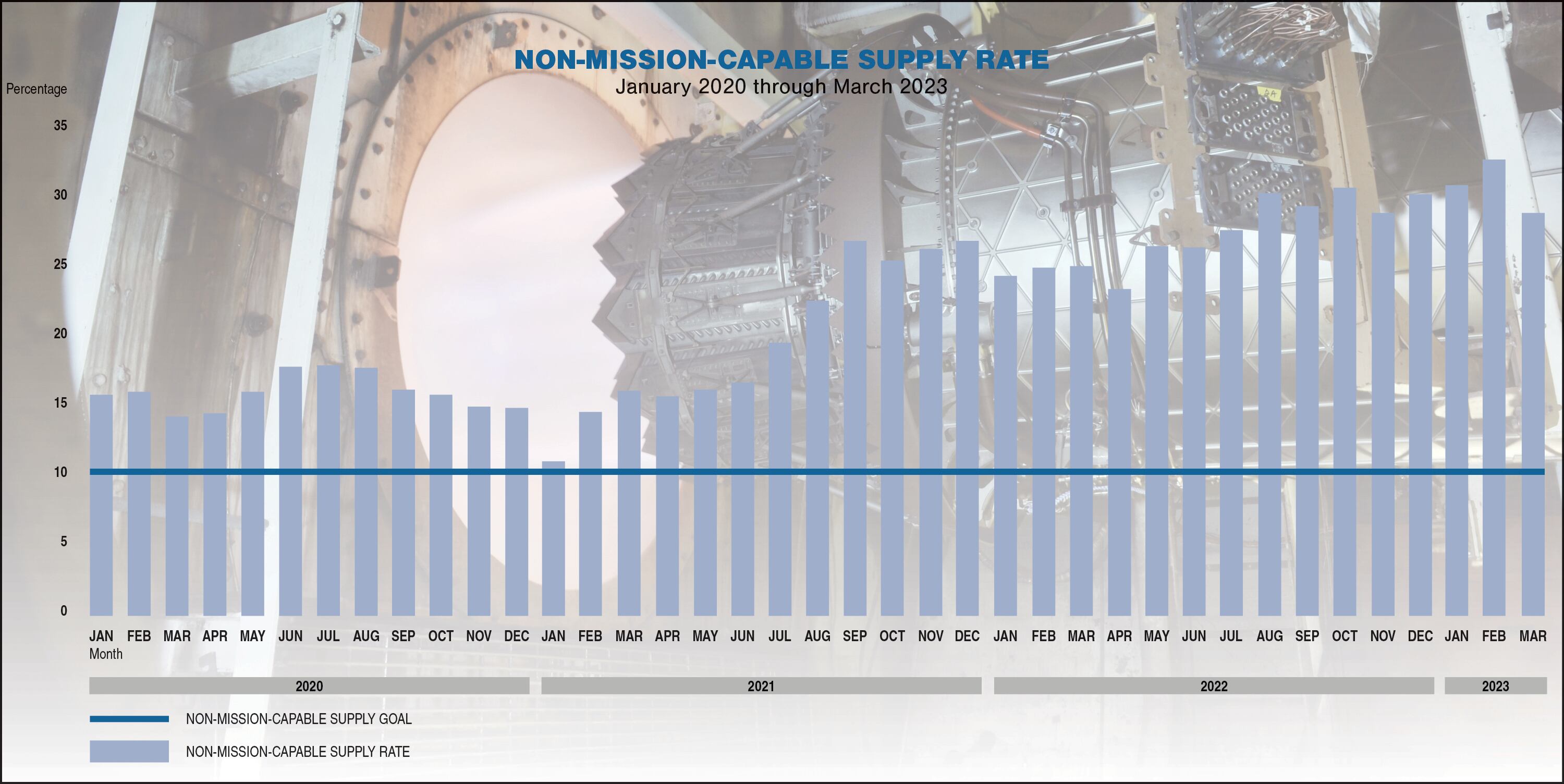

On the Joint Strike Fighter side, the F-35 JPO wants to see 64% of its planes mission capable, 21% non-mission capable due to waiting on supply parts, and 15% non-mission capable due to waiting on maintainers to do a job. Those numbers will eventually shift to have more planes ready and fewer planes waiting on parts and maintenance work.

Smith’s fleet of Navy F-35Cs is already beating those goals. He told Defense News his wing already surpassed the 64% mission-capable goal. In addition, it’s had a non-mission-capable maintenance rate — the only rate the wing can truly affect on its own — below 15% from January 2023 through March 2024.

‘Ebbs and flows’

Even as Smith and his Joint Strike Fighter Wing do what they can from Lemoore to boost readiness, some things are out of their hands.

Smith is stymied by the same parts challenges outlined in the GAO report.

“Parts availability ebbs and flows,” he said. However, the JPO has a Lightning Sustainment Center with a Navy representative on staff, who Smith can call when there’s a delay in getting a needed part flown to Lemoore.

To increase communication, Smith said that Lightning Sustainment Center representative also sits in on Maintenance Operations Center meetings. He noted cross-community meetings were a big part of the 2018 Naval Sustainment System-Aviation reforms.

Warren Scovell, the director of fleet readiness at the F-35 Joint Program Office, said the organization is closely tracking feedback regarding which parts cause the biggest headaches for the fleet.

The JPO had a top 10 list of readiness degraders, which was later expanded to 20 and then 40. Over the last year, Scovell said, the office eliminated 13 of the top 20 degraders — in many cases, replacing parts with more reliable ones that won’t break as often and therefore won’t be such a drag on the supply system.

Though some parts have remained thornier than others — Defense News reported last year canopies and the electro-optical distributed aperture system were two tough ones that affected all three models of the F-35 jet — Scovell said the fleet can get down to the goal of 21% non-mission capable supply by the end of this year, and then reduce that even further. That rate shows how many planes are down while awaiting supply parts.

Asked if that would drive down cost, he replied: “Absolutely yes.”

“The No. 1 focus is always to keep parts on wing longer. So whenever you can do that, you will absolutely drive down cost,” he added.

Similarly, Smith and the head of Fleet Readiness Center West, Capt. Joseph Hidalgo, agree they’d like the center to perform intermediate maintenance on F-35s instead of outsourcing that to industry. However, that’s up to the JPO.

In the meantime, Smith is trying to apply Naval Sustainment System-Aviation principles to monitoring depot performance data, if only to demonstrate to the JPO what the Navy is experiencing at industry-led depot availabilities and how it affects F-35C readiness.

Scovell said the JPO is working on a new sustainment strategy that would move more work away from industry and to the services. He said that effort is ongoing and declined to provide a timeline for its release, but noted it would allow fleet readiness centers to play a bigger role in F-35 sustainment, including uniformed personnel conducting more maintenance and the services buying their own spare parts.

In a statement, Lockheed Martin said it stands “ready to partner with the government as plans are created for the future of F-35 sustainment.” The company noted it is working with the government to “accelerate depot activations to increase repair capacity” and said that since 2015, the firm has lowered its portion of the F-35′s cost per flight hour by 50%.

Keeping costs low

The naval aviation budget is tight this year and expected to remain that way.

In fiscal 2025, the Navy asked for 13 F-35C jets, down from a recent 19-per-year rate to reflect congressionally imposed spending caps. That number is expected to grow as high as 24 jets a year later this decade — but that comes as aviation procurement needs will balloon by 34%, ship procurement 35%, and weapons procurement 71% in the coming years, according to Navy FY25 budget materials.

It’s unclear if the Navy will be able to secure that kind of funding to grow its fleet. And even if it does, it then has to pay to sustain the new platforms.

“The entire naval aviation enterprise is acutely aware of the burgeoning costs required to sustain air operations and remains focused on increasing lethality and readiness through process improvement and driving efficiency at all levels of the organization,” according to a Navy budget document.

When F-35C sustainment overruns its estimates, the Navy has to reconsider the whole portfolio.

“There is not a single bill-payer for higher-than-expected F-35C maintenance costs. The Navy evaluates cost increases through the lens of the larger Navy priorities and balances the budget in accordance with strategic guidance; this can result in reductions in other areas of the budget,” a Navy spokesperson told Defense News.

The spokesperson noted the cost per tail to operate the F-35C has decreased as the aircraft inventory grows, and that both the JPO and naval squadrons are finding ways to improve performance and lower cost.

Stokes and Smith said they are seeking to minimize mishaps: engines sucking up debris that damages them from the inside, crew damaging planes while towing them, canopies being scraped during operations and more. When they can avoid these mishaps, they pay less to repair the damage.

Hidalgo and Smith are closely monitoring F-35C corrosion and looking to take early intervention steps, after corrosion proved to be a costly challenge with the Super Hornets and the legacy Hornets before them.

Scovell said the JPO is about 90% complete in writing a structural repair manual to send to squadrons so they can do more of their own maintenance on the flight line. He said the squadrons doing this work themselves would be faster and cheaper than waiting on contractor maintenance.

Wittman, who also chairs the Tactical Air and Land Forces Subcommittee, said the Navy and Air Force are now turning to unmanned wingmen — also known as collaborative combat aircraft — to achieve “affordable capacity” in tight budgets.

He said the U.S. military cannot afford — monetarily or operationally — to lose out on F-35 readiness.

“The combined force in the Indo-Pacific will rely on F-35s in a near-peer fight: South Korea, Japan and Australia all operate the aircraft,” he noted. “Losing that capability from readiness delays, or not achieving the required aircraft capacity due to cost overruns, will inevitably hamper our ability to respond to threats and aggression in the region.”

Wittman also said he hopes the services learn from the F-35′s cost and readiness challenges when pursuing future programs.

“Contractor-led sustainment of the aircraft will eventually phase out in the coming years as it transitions to service-led governance,” he said. “Although contractor-led sustainment was the primary acquisition strategy initially, we are watching setbacks of that original acquisition sustainment strategy play out in real time.”

Correction: A previous version of this story erroneously described the meaning of the bar graphs. Their respective captions have been updated.

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.