On Nov. 12 the European Space Agency's Rosetta Mission landed on a comet more than 300 million miles away.

But while this technological marvel and the spectacular pictures it has beamed back to earth have reminded the world of the incredible things achieved in space exploration, the last few weeks have also been a reminder of the risks. A pilot on a test flight of Virgin Galactic's sub-orbital space plane died when the aircraft broke apart in flight over the Mojave Desert. Another pilot survived but was seriously injured.

And three days earlier, on Oct. 28, an Antares rocket on an unmanned resupply mission to the International Space Station exploded on the launch pad at NASA's Wallops Island flight facility in Virginia.

Few men on earth know more about the hazards of space flight than distinguished naval aviator and NASA veteran astronaut of the NASA space program retired Capt. Jim Lovell. Lovell logged more than 7,000 flight hours during his naval career and more than 715 hours in space.

He served on Gemini 7 and 12, and as mission pilot on Apollo 8: the first voyage to the moon. He is best known as the mission commander for Apollo 13, during which Lovell and his crew – brilliant engineer and test pilot Jack Swigert and Air Force Capt. Fred Haise – successfully returned to Earth after a crippling explosion on their way to the moon. The events were chronicled in the film, "Apollo 13," with Tom Hanks playing Lovell.

Lovell, 86, is now leading a new mission: leading a fundraising campaign for the Smithsonian's venerable National Air and Space Museum. Lovell sat down with Military Times two days after the Antares rocket explosion.

Q. What were your thoughts watching the Antares rocket explode?

A. That was quite a spectacular explosion. This is a new era for NASA or, I should say, for our space efforts. NASA has had contracts with three different [companies]organizations: SpaceX, Orbital Sciences and Boeing has been doing some work in the space field. It's a setback for Orbital Sciences. I don't think they are planning any manned mission. Boeing and SpaceX are. But they are doing unmanned missions and this one didn't go so well.

Q. What's your take on the state of the space program, now that NASA has no shuttle program?

A. Well, I'm somewhat disappointed in the space program. I think we'd have been a lot further if we had kept the Constellation Program in favor of the commercial outfits like SpaceX.

One of the things that concerns me is that back when I was in the program, we hadve very strict oversight and safety regulations for man-rated vehicles. Look at what happened this week. Now Orbital Sciences doesn't do manned flights, but it raises questions: What kind of control and did NASA have? Luckily it doesn't look like any of NASA's equipment was damaged too badly.

Q. As the space program goes forward, what do you think military members bring to the endeavor?

A. Several things. First of all, they are good people who follow instructions and know how to lead in stressful circumstances. Second, most folks in the military have an engineering background of some sort, whether it's working with equipment or from their education background.

Third, well if you look at the early groups, we were test pilots; we kind of lived our lives on the edge. We were used to taking risks — calculated risks.

Q. You were part of the legendary Apollo missions to the moon. What is the next big leap?

A. I'd like to see us go back to the moon. First we need to continue to go back to the International Space Station. But as far as outer space goes, the moon is going to be the prominent thing. We barely looked at it and we could do a little bit more exploring. That would give us the confidence and infrastructure back that we once had.

Once we do that, we'll have the confidence and the technology in place to go to Mars.

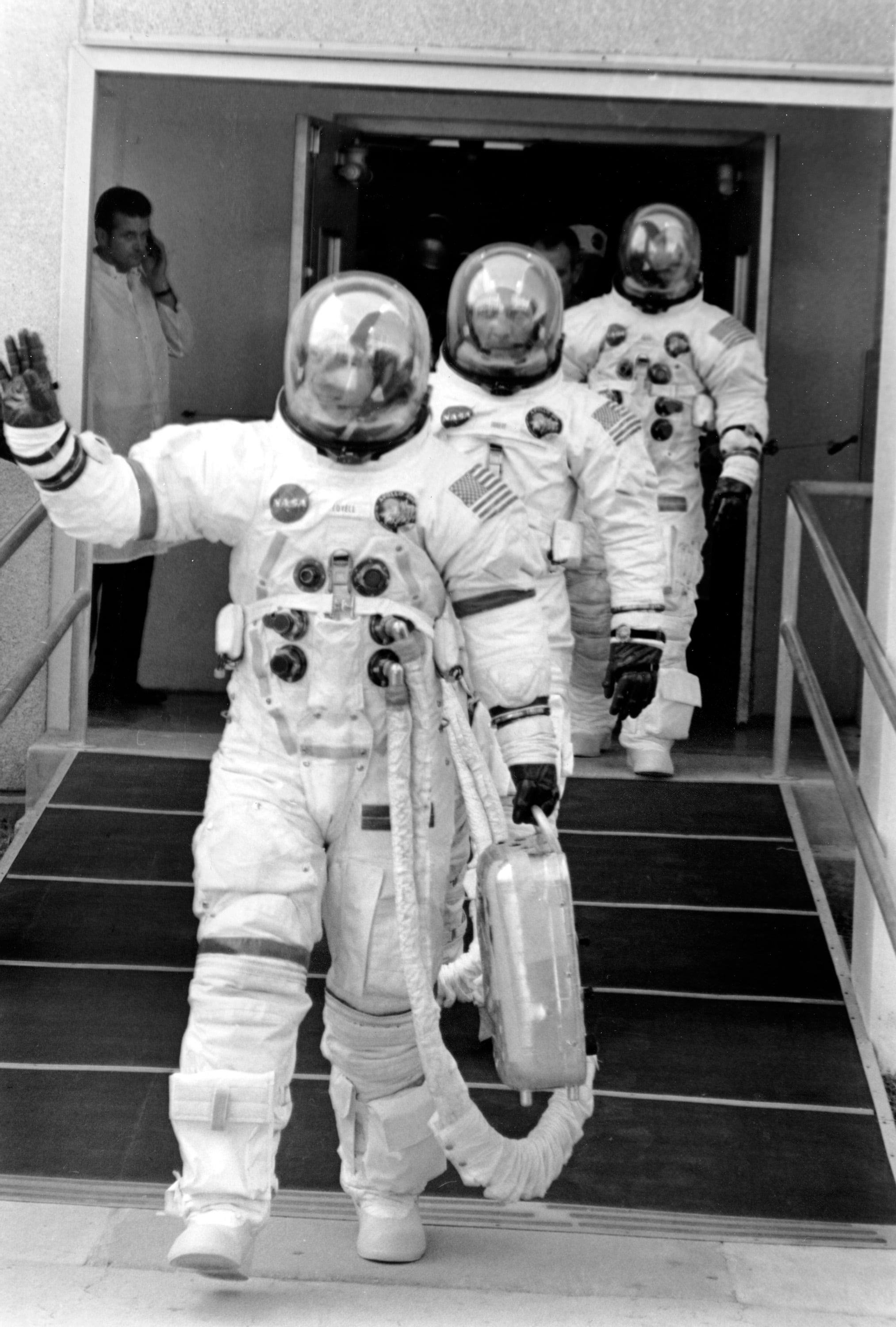

Flight Commander Jim Lovell waves as the crew of the Apollo 13 lunar landing mission moves to the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970.

Photo Credit: AP photo/NASA

Q. You have spent about a month of your life in space. That's a long time. But the one-way trip to Mars is likely to take at least 300 days. Can humans physically handle that?

A. Submarine sailors stay in the water for up to six months, so we know it's possible. As far as the zero gravity environment, I found that once you get used it, it is a tranquil, almost lethargic atmosphere. The problem is you have to stay in shape, so there would have to be equipment to do that on the spacecraft.

One problem would be the radiation. We don't really know what the effects would be of being outside [our atmosphere] for so long.

As for me, to tell you the truth, I haven't [had any lingering effects]. According to Einstein, I think it added about seven-hundredths of a second to my life

For the young pilots out there who might want to become astronauts, what advice would you offer them?

Well it was a great program for me, one where you do a lot of engineering work to make a flight happen. What kind of advice I'd give? I don't know because I'm not sure what's going to happen to the space program.

Things are slowing down and they might have to wait a long-long time to do what they want to do. Aviators like to fly and there are plenty of planes on earth to fly. As an astronaut, it might be a long time between flights.

David B. Larter was the naval warfare reporter for Defense News.