When Navy Lt. Cmdr. Edward Lin was first arrested at the Honolulu airport in 2015 on a flight to China, military investigators thought they had uncovered an espionage case of epic proportions – a Mandarin-speaking Asian-American military officer accused of leaking highly sensitive U.S. military secrets to Chinese and Taiwanese officials.

After two days of intense interrogation, Lin confessed to telling a recently retired Taiwanese naval officer and others some highly classified details about the U.S. Navy's weapons programs, including the Long Range Anti-ship Missile under development, the high-speed rail gun and the Laser Weapon System being tested in the Persian Gulf, according to statements made at a recent motion hearing in a courtroom in Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia.

So military investigators likely thought they had a key witness when they sat down to depose that retired Taiwanese naval officer, Justin Kao, who is also a Virginia Military Institute and Penn State grad and who worked at the unofficial Taiwanese embassy in Washington.

However, according to a copy of Kao's Aug. 2 deposition transcript that was obtained by Navy Times, Kao told investigators very little that would help convict the U.S. Navy officer.

Did Lin ever share information about the Navy's laser weapon? Kao said no.

Did Lin say anything about the anti-ship missile program? Kao said he'd never heard of it.

Did Lin disclose information about the rail gun? Kao said Lin mentioned it once, at a barbecue at Lin's house, when Lin casually recalled a visit to the Navy research test lab when one of the technicians gave Lin a fragment from a test target as a souvenir. Lin seemed to be showing off to a friend rather than disclosing military secrets, Kao said, according to the deposition's transcript.

As Lin's trial date in March approaches, Navy lawyers have a problem: There's very little evidence of any espionage by Lin and there is growing doubt that the government can prove that Lin was a spy, according to a trove of documents obtained by Navy Times and a series of interviews with officials inside and outside the military.

At a court hearing here in November, government attorneys conceded that, despite Lin's initial confession, they had no direct evidence corroborating much of what Lin supposedly confessed to. Furthermore, there is little or no evidence he transferred classified information to Taiwanese officials aside from two emails that were classified "secret" after the fact.

A copy of the report from the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, obtained by Navy Times, found no evidence that Lin was receiving any kind of payment for the alleged spying. The redacted NCIS report obtained by Navy Times appears to reveal a wide gap between the most damning crimes Lin was originally accused of and the evidence prosecutors have in hand now.

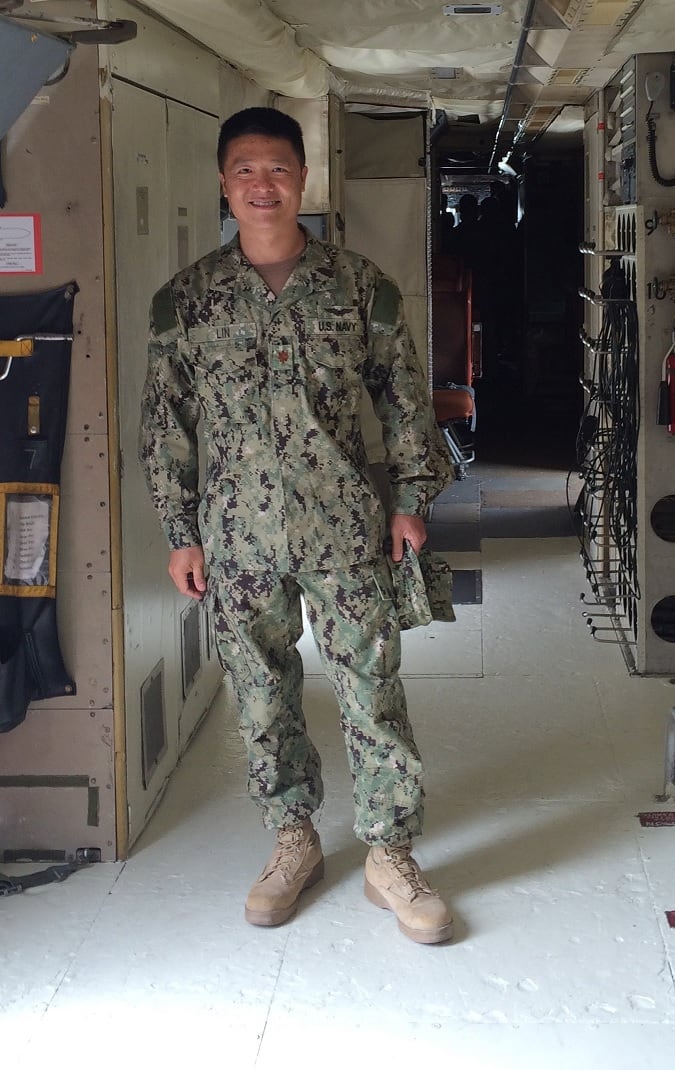

Lt. Cmdr. Edward Lin is facing charges of espionage and attempted espionage, but a Navy Times investigation found scant evidence that Lin was a spy.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the family of Edward Lin

Lin, a Taiwanese-American who has been an U.S. citizen for nearly two decades, remains locked up in the Chesapeake Brig, charged with espionage and attempted espionage, charges that could result in a life sentence.

For now, the government's spy case against Lin appears to boil down to two emails sent to a Taiwanese political lobbyist named Janice Chen — a representative of Taiwan's pro-U.S. and pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party — that U.S. Pacific Command deemed classified after the fact. Lin's attorneys will likely question whether those emails should have been classified at all.

Another pillar of the case against Lin involves his series of encounters with the undercover FBI agent Katherine Wu, according to statements made at the hearing and interviews with several people familiar with the case who declined to speak on the record fearing government retribution.

Given the lack of evidence corroborating some of the things Lin is said to have confessed to, Lin's defense team could focus on a claim that the incriminating statements he himself made were false and coerced, said Tim Parlatore, a former surface warfare officer and New York defense attorney who handles military cases pro bono.

"There is a lot of information out there about false confessions and there are expert witnesses who can explain the psychology of why someone would confess to something that they didn't do," said Parlatore, who is not directly involved in the Lin case but reviewed documents from the case at the request of Navy Times.

A confession is a powerful piece of evidence, but most people don't understand the circumstances under which people confess to crimes they didn't do, often under intense interrogation by law enforcement, Parlatore said. And military members are uniquely susceptible to confessing crimes they did not commit, he added.

"We are indoctrinated into the idea that when you are confronted for a mistake, you take responsibility, you fall on the sword and you ask for mercy," Parlatore said.

Lin's relationship with NCIS

Lin had a security clearance higher than Top Secret and had access to some of the Navy's most sensitive secrets. At the time of his arrest, he was working for an airborne signals exploitation squadron called Special Projects Squadron 2. Lin is also a former enlisted sailor who started his career in the nuclear force.

There is no doubt that the investigation of Lin revealed some highly unusual activities. Lin had many contacts with high-ranking Taiwanese officials that he should have — but failed to — disclose to the U.S. Navy.

Yet, his story is complicated by evidence that Lin had a prior and undisclosed relationship with NCIS and the FBI years before the spying allegations. The nature of that relationship is unclear, but it could have involved Lin and his rare Mandarin language skills in a shadowy intelligence or counter-intelligence operation.

According to an investigation report obtained by Navy Times, part of Lin's official duties with the FBI and NCIS included maintaining contact with Taiwanese officials at the Taiwanese diplomatic outpost in Honolulu and Taiwan.

Lin was stationed in Hawaii with U.S. Pacific Fleet between 2007 and 2009, according to his official bio.

The investigation shows clearly that Lin did not cease contact with Taiwanese officials after he left the program. In fact, during his time as a congressional liaison in 2012 and 2013 while working in the Navy's Pentagon budget shop, the investigation documents nearly 50 emails to and from Taiwanese officials.

Most of the email exchanges are with Kao, and the contents are hardly earth-shattering. Kao asks Lin about U.S. Navy customs and uniform items. In one exchange, Kao asked Lin about the U.S. military's transition to an all-volunteer force after Vietnam, and Lin forwarded him a Congressional Budget Office report on the subject.

Lin's failure to disclose contacts

Lin's friendship and repeated contacts with Taiwanese officials raised questions because he did not report them to his security clearance managers — a major misstep for an officer with his level of access, experts say.

Investigators found evidence that Lin repeatedly left the country despite routinely putting his home address in northern Virginia down on his leave chit — including a trip to Taiwan with his wife when he met with the Taiwanese Chief of Naval Operation, Vice Adm. Richard Chen. Lin knew the Taiwanese CNO from Lin's time working at the U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters in Hawaii, according to Kao's deposition.

Also raising red flags with the government, however, was Lin's request that Kao not tell American diplomats in Taiwan about his meeting with Chen.

"The problem is that he had these foreign contacts he was communicating with and he didn't report them" said Bryan Clark, a retired submarine officer who has at various points in his career acted as the security officer in charge of managing security clearances for commands. "And not reporting the contact opens you up to all sorts of criticisms."

According to the 65-page transcript of Kao's deposition, Kao and Lin met from time to time for lunch, visited each other's houses. According to the investigation the most damning evidence appears to be an email about a Navy weapons program — specifically about submarine-launched torpedo test results. But the government found no evidence that Lin shared the information and, in fact, Lin seemed to suggest Kao to go through official channels for the information because it was classified, according to the investigation.

Kao described a cordial relationship between himself and Lin: They'd meet for barbecues and occasionally emailed Lin about open-source information he was having trouble locating online.

Kao said his job at the unofficial Taiwanese embassy was to glean open-source information and pass it to Taiwan's military intelligence division — most of what he'd do is translate press clippings into Chinese.

Kao's job also frequently required that he interact with the U.S. Navy's office of International Engagement — N-52. If Kao had trouble getting something from N-52, he'd email his friend Lin who'd occasionally find stuff buried on the Navy's unclassified websites and pass it along.

"Move on to real crimes"

Legal experts who reviewed the documents for Navy Times disagreed on the strength of the government's case against Lin.

David Sheldon, a Washington-based attorney with experience in military law said the contacts Lin maintained and didn't report, as well as his sharing information with his contacts, did raise a lot of red flags.

"The fact is, you have a senior Naval officer providing significant information to representatives of the Taiwanese military establishment and government (both here and abroad), socializing with these individuals, traveling to Taiwan on multiple occasions, failing to disclose multiple contacts with foreign nationals and travel to Taiwan, as well as ostensibly providing classified information." Sheldon said.

But another military attorney was more skeptical. Jeffrey Addicott, a retired Army lawyer who now teaches at St. Mary's University School of Law in Texas, said that it seemed the prosecution was far more aggressive than the evidence warranted.

"Even though the initial suspicions of the investigators turned up nothing of great significance that would warrant a criminal trial, the system is unwilling to admit this — particularly after expending two years of investigation efforts — and chooses instead to press forward," Addicott wrote in an email. "I have seen this pattern manifest itself many times in my experiences. If they would only sit back, take a deep breath, and pursue justice, they would be able to move on to real crimes."

What is clear is that last year's sensational headlines were far from accurate. Unnamed government officials told reporters that Lin was suspected of spying for China and Taiwan, despite there being no evidence in the NCIS investigation that Lin ever exchanged sensitive information with anyone from China.

Other accusations of misconduct attributed to unnamed officials included an April 11 article in the Daily Beast with the headline " Did an Accused Navy Spy Trade Secrets for Sex?" which cited defense officials speculating that Lin was paid in sex for government secrets. The Navy later dropped Lin's initial charges of prostitution and adultery.

In a statement to Navy Times, Lin's civilian attorney maintained his client's innocence.

"Lt. Cmdr. Lin's trial was never about 'sex for secrets' or 'spying for China' as inaccurately described by unnamed Navy and government officials last year," Larry Youngner said. "Lt. Cmdr. Lin's case is about a patriotic U.S. sailor who would never harm his country. Eddy loves the USA. That is why Lt. Cmdr. Eddy Lin pleaded not guilty. His Defense team looks forward to confronting the remaining government case against him."

When asked to describe what evidence the government had that tied Lin to the espionage charges, a Navy spokesperson declined to comment.

"We cannot disclose the elements of the case that you are requesting – the facts of the case will be presented during the trial, not before through the press, in order to preserve the integrity of the judicial process, to ensure LCDR Lin's right to a fair trial by an impartial jury, and to protect the interest of the US Government," said Fleet Forces Command spokesperson Lt. Cmdr. Stephanie Turo.

David B. Larter was the naval warfare reporter for Defense News.