WASHINGTON ― A day after the U.S. formally pulled out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, Defense Secretary Mark Esper said he wants to deploy a conventional ground-based missile that could travel within the agreement’s prohibited range “sooner, rather than later.”

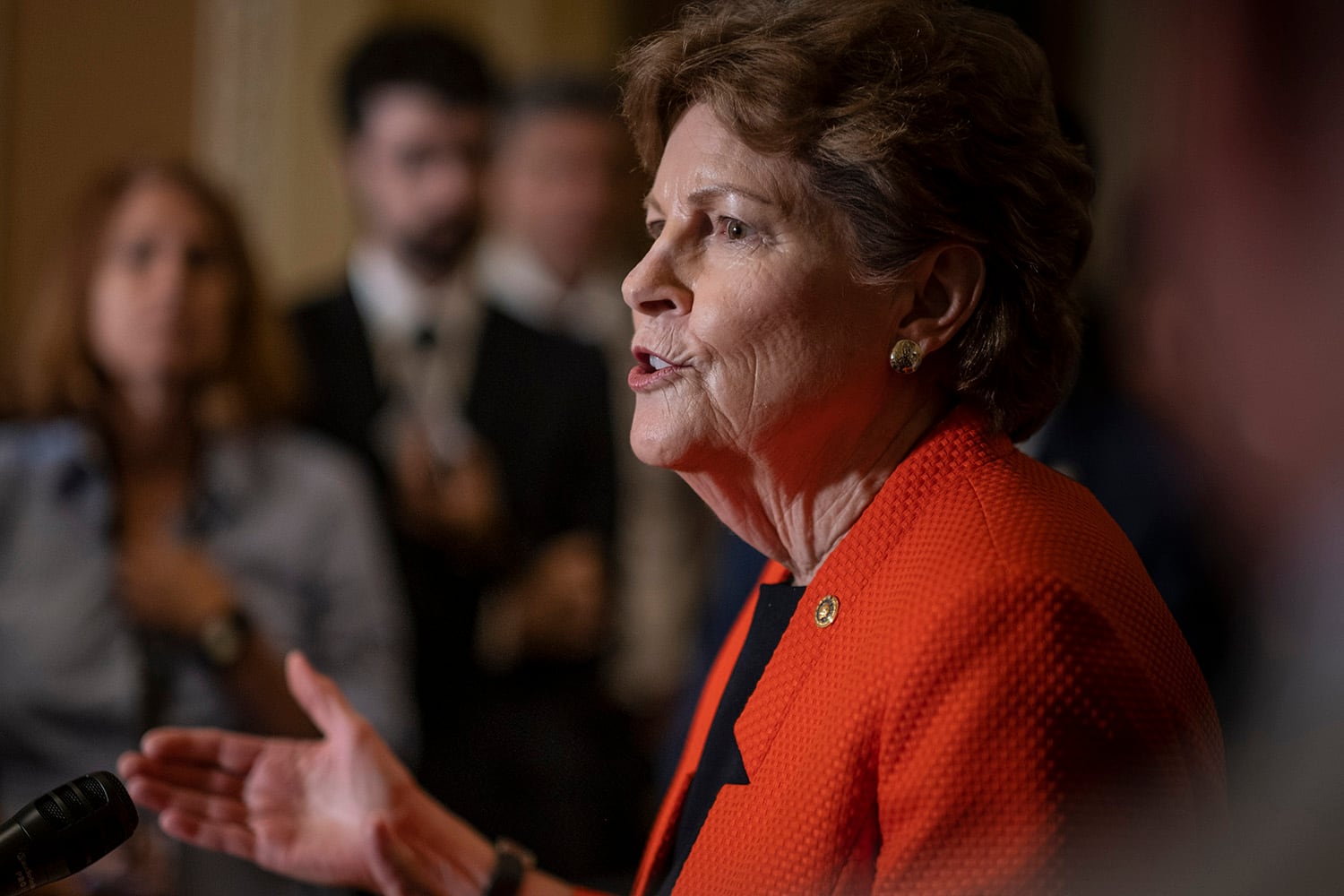

Beyond the thorny international politics, the Pentagon would also have to successfully navigate a divided government on Capitol Hill, where Democrats have criticized President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the treaty and his administration’s argument for new missiles.

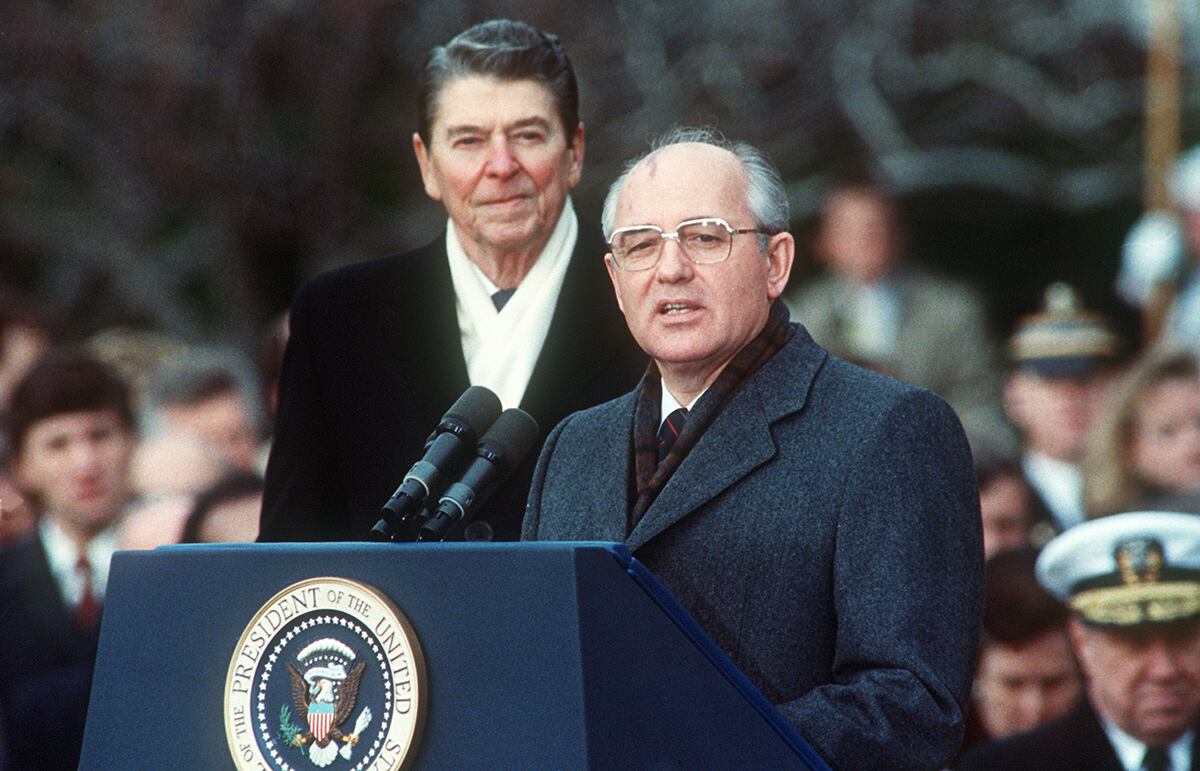

The U.S. on Friday formally suspended its compliance with the landmark INF Treaty, a 1987 pact with the former Soviet Union that banned ground-launched nuclear and conventional ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,000 kilometers. The U.S. and Russia had traded accusations of treaty breaches for more than a decade.

Critics of the withdrawal said the administration did little to preserve the treaty and that its demise could spark an arms race. Supporters said the pact needed to be scrapped because Russia had long flouted it and that it limited efforts to compete with China, which never joined the treaty.

On Capitol Hill, a flashpoint in the fight is $96 million the administration requested to research and test ground-launched missiles that could travel within the agreement’s prohibited range.

The House passed a spending bill that would deny the funding ― and a defense authorization bill that would deny it until the administration shares an explanation of whether existing sea- and air-launched missiles could suffice, among other information.

RELATED

When the House bills are reconciled with their Senate versions, Senate Republicans are expected to push back. It’s unclear how the Senate defense spending bill will address the matter because it hasn’t been written, but the Senate authorization bill supports the administration’s request for new weapons.

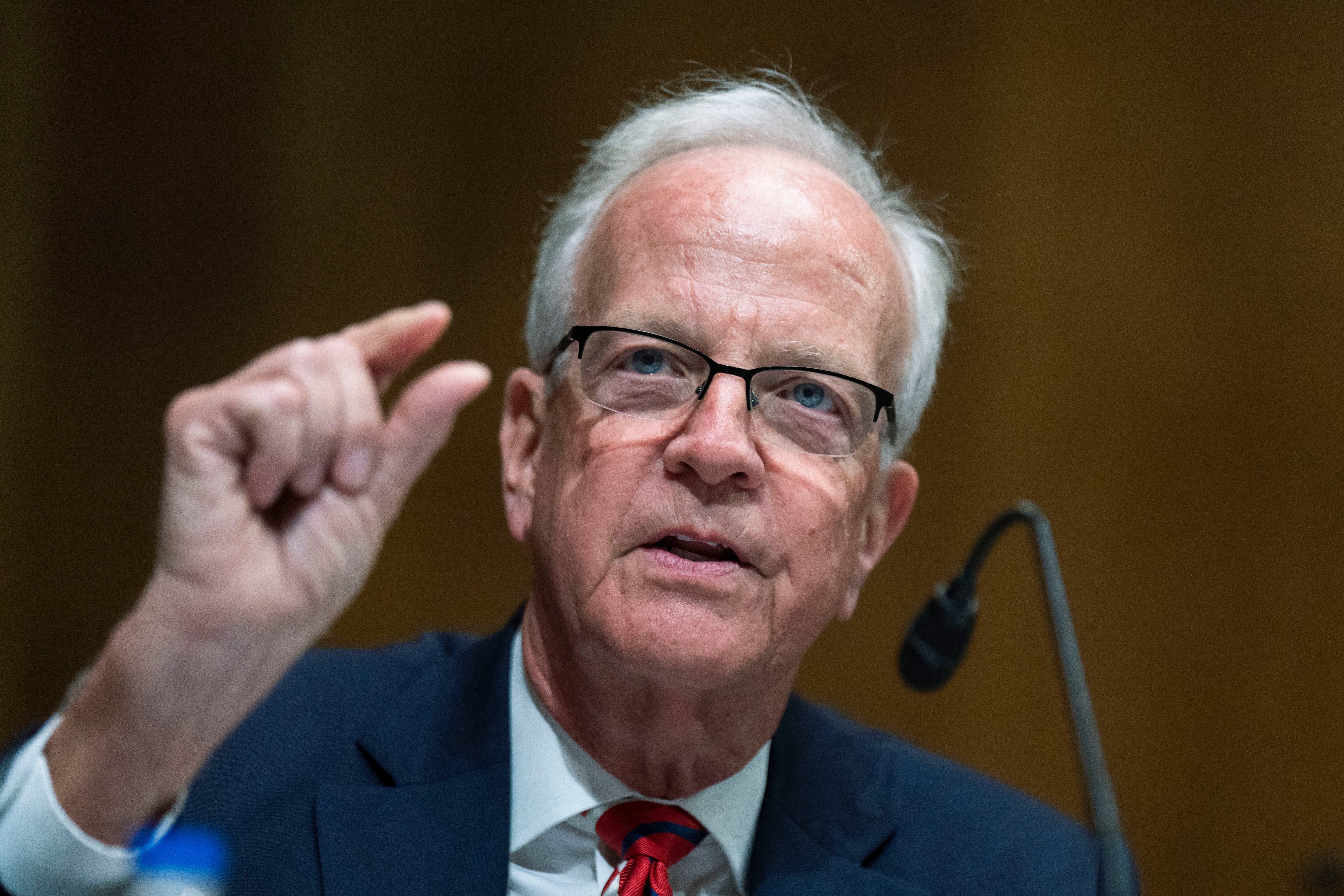

Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., and the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Airland Subcommittee, will be one lawmaker to watch. He has criticized the treaty and pushed for funding to research missiles outside its limits, mindful that China already has such weapons.

“We have tens of thousands of American troops and families in range of Chinese missiles,” John Noonan, counselor to Cotton on military and defense affairs, said this week. “INF is dead. Russia killed it. Congress should work together on this. Any system that complicates Beijing's ability to plan and prosecute an attack should be taken seriously and pursued aggressively.”

Critics warned that the costs of deploying the missiles outweighs the benefits, and said the administration lacks a plan to mitigate the risks to stability in Europe and Asia from withdrawing from the treaty.

“Developing and fielding U.S. INF Treaty-range missiles is militarily unnecessary, would force difficult and contentious conversations with and among allies, and would likely prompt Russia and China to take steps that would increase the threat to the United States and its allies,” said Kingston Reif, director for disarmament and threat reduction policy at the Arms Control Association.

Indeed, China said Tuesday it “will not stand idly by” and will take countermeasures if the U.S. deploys intermediate-range missiles in the Asia-Pacific region.

The director of the Chinese Foreign Affairs Ministry’s Arms Control Department, Fu Cong, also advised other nations — particularly South Korea, Japan and Australia — to “exercise prudence” and not allow the U.S. to deploy such weapons on their territory, saying that would “not serve the national security interests of these countries.”

Esper, during a tour of Indo-Pacific Command’s theater this week, told reporters he is seeking non-nuclear missiles in these ranges to “deter conflict” within “months,” but could not immediately say which ally would host them or when they could be built.

Esper later clarified that he had not asked any allies on the trip, that none have declined and that the process might take “a few years.”

“Somehow this got spun along to a point where I guess some people thought we’d deploy missiles next week, or something like that,” Esper said. “We are quite some ways away from that. It’s going to take, again, a few years to actually have some type of initial operational-capable missiles — whether they are ballistic, cruise, you name it — to be able to deploy."

There would have to be “a lot of dialogue” with regional commanders and “with our partners: Where is the best place to deploy these systems?” Esper said.

The battle on the Hill

To develop and deploy such a new missile over years, or even months, requires the Pentagon to also obtain buy-in from lawmakers over multiple budget cycles.

The current fight over $96 billion in medium-range missile funding includes two pots of money: $20 million that comprised the Army’s request for mobile, medium-range missile research; and a $76 million “classified reduction” from an unrelated “prompt global strike capability development” line item.

The funding would cover tests for three systems, according to a congressional source. The $20 million Army system is meant to be ballistic or hypersonic, and the $76 million could be for a land-based cruise missile and ballistic system.

House Democrats passed an amendment to the annual defense authorization bill to withhold all of it until the Pentagon presents a proposal to replace the INF Treaty; details military requirements for INF Treaty-range missiles; identifies a country in Europe or Asia willing to host the missiles, and presents an analysis of whether existing sea- and air-launched missiles could suffice.

Even before the bill reached the floor last month, House Armed Services Committee Chairman Adam Smith, D-Wash., removed the $76 million in his draft of the bill, with the note, “Lack of justification — awaiting policy.” His committee later defunded the Army’s $20 million during its markup.

The reduction was not intended to set policy against the entire category of ground-based conventional systems, according to one HASC staffer. “Our view is we didn’t get the information to justify that program,” the staffer added.

Which Asian ally would accept American road-mobile, conventional missiles is no small matter, as that country would risk economic and diplomatic retaliation from Beijing, according to an analysis by Pranay Vaddi of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

South Korea, which seemed unenthused Monday, was informally sanctioned by China after its 2016 deployment of a U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense battery to help defend against North Korean missiles.

On Capitol Hill last month, House Democrats also defeated an amendment that would have restored the $96 million to the lower chamber’s spending bill. It failed 203-225, despite the argument from HASC member Mike Gallagher, R-Wis., that the research was not prohibited under the treaty and the missiles are vital to protecting U.S. troops stationed in the Asia-Pacific region. (Gallagher’s amendment attracted 13 Democrats.)

Republicans urged their colleagues to quickly face up to China’s arsenal of conventional ground-based missiles ― which outrange the ground-based missiles available to U.S. troops in the region and are much cheaper than America’s ships, fighters and bombers.

“Going forward, I would love to see some kind of treaty between the U.S., Russia and China. But that’s not in the works,” the HASC Readiness Subcommittee’s ranking member, Rep. Doug Lamborn, R-Colo., said during in a floor speech last month.

The Pentagon has not yet announced a development track for any future mobile, ground-based missiles in the INF Treaty range.

One potential system is the future Precision Strike Missile, or PrSM, meant to replace the Army Tactical Missile System in the field in 2023. Though it’s designed to travel 499 kilometers, Army officials have said both competitors ― Raytheon and Lockheed Martin ― could modify their offerings to fly further.

Esper, formerly the secretary of the Army, said the service is prepared to begin extending the missile’s range. To reach an “effective range, that would take quite some time. I honestly can’t recall whether it’s 18 months or longer, but my sense is it would likely take longer," he said.

Beyond PrSM, Lockheed Martin’s Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile, or LRASM, and Raytheon’s Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile could be modified and fielded as ground-launched theater-range missiles within years, according to a report by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

Jen Judson in Huntsville, Ala., and The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Joe Gould was the senior Pentagon reporter for Defense News, covering the intersection of national security policy, politics and the defense industry. He had previously served as Congress reporter.