Most Military Times readers believe they’ve been targeted with disinformation from malicious groups, politicians and news media, and they think the responsibility to stop its spread falls to everyday people, a recent survey found.

Readers are dubious about information posted to social media and confident in their ability to spot disinformation — but they don’t have faith in their neighbors or in politicians to do the same, the results said. In a test designed to see whether readers could differentiate between real and false information online, about 90% succeeded.

While most respondents called out false claims about the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol being a “PsyOp,” or psychological operation carried out by the government, there were still hundreds who answered that the claim was credible, said Scott Parrott, a professor in the journalism department at the University of Alabama who helped put together the questionnaire.

“What the results are telling me is that they’re skeptical,” Parrott said. “They’re skeptical of news media, they’re skeptical of politicians and they’re skeptical of social media.”

However, a “disturbing” number of people still indicated support for the most extreme principles of QAnon and the “Great Replacement” theory — conspiracies that have prompted violence in recent years, researchers said.

Military Times and the University of Alabama conducted the survey with Military Veterans in Journalism to discern how readers perceived disinformation and extremist beliefs ahead of the November presidential election. More than 2,400 members of the military community participated, including veterans, service members, contractors and family members. Their political ideologies were split: one-fourth identified as Republicans, 14% as Democrats and 52% as Independents.

Most readers could spot disinformation

The World Economic Forum declared disinformation as the most severe risk over the next two years, writing in its annual report in January that the spread of false information could undermine the legitimacy of newly elected governments across the globe and result in violent protests, hate crimes and terrorism.

Researchers are already seeing instances of Russian interference in the U.S. this year, including a coordinated effort around the Texas-Mexico border crisis to amplify calls for a civil war, according to Kyle Walter, head of research at Logically, a British tech company that uses artificial intelligence to monitor disinformation around the world. Walter said Russia is likely to increase its spread of falsehoods in the run-up to the November election, likely focusing on immigration and the U.S. economy.

“The perception at times is that Russia is seeking to help one candidate win an election over another candidate,” Walter said. “What they’re really trying to do is create chaos and make people question the process and validity of the democratic process and the integrity of the election.”

Election deniers are specifically recruiting veterans and service members this year to exploit their social capital and bring legitimacy to the cause, argued Human Rights First, a nonprofit human rights organization. In a report, the nonprofit urged veterans to be wary of calls to “restore election integrity” or “catch the cheaters in real time” and instead leverage their credibility to counter conspiracies about the democratic process.

In the survey, 57% of Military Times readers said they had personally been targeted with disinformation, and another 23% were unsure. They believe disinformation is spread mostly by malicious groups seeking power, followed by the news media, politicians and independent actors.

“It’s a bad sign that so many people have been targeted, and a good sign that so many people recognize at least part of the time when they’ve been targeted,” said Rachel Goldwasser, a senior research analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

When asked about who’s responsible for stopping disinformation, 87% of respondents said U.S. adults as individuals bear that burden. Of the respondents, 73% said members of the mainstream media also share responsibility, and about half think government and community leaders, academics and social media companies should help stop the spread of disinformation. Only 17% said foreign government agencies are responsible for stopping it.

Overwhelmingly, Military Times readers said they could identify disinformation — about 92% were confident they could spot it. They generally believe their friends and family members can identify disinformation, too. About 64% think their friends could identify it, and 61% think their families can.

Just over half of respondents said veterans as a population can identify disinformation, but they were less confident in politicians and people in the towns where they live. About 42% think politicians can discern real and false information, and 30% think their neighbors can tell the difference.

“It’s common for people to overestimate their ability to identify disinformation,” said Wendy Via, a co-founder of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism.

Parrott described that as the “third-person effect,” referring to a theory coined in the 1980s that states individuals perceive others as being more influenced by mass-media messages than they are.

“It’s almost as if you think better of yourself, like ‘I’m not affected. I can figure it out. I can parse it,’” Parrott said. “But when it comes to family or friends, they say, ‘They can parse it, too, but not as well,’ and then it gets to townsfolk and they say, ‘No, they can’t.’”

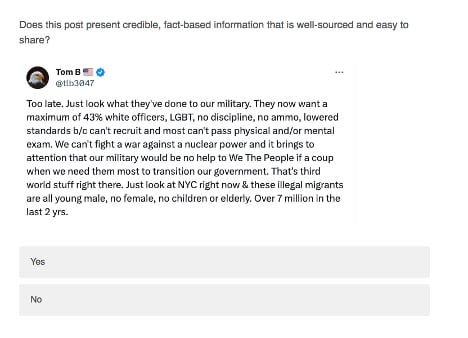

The survey put readers to the test. It asked respondents to identify several posts on X, formerly Twitter, as being real or false information. Many of them were correct with their responses, but there was confusion among hundreds about what was real or false.

Via, who has conducted extensive research on disinformation and extremism, said voluntary surveys were a helpful way to understand people’s thinking, but it was important to take into account the demographics of who responded.

“For the folks who are willing to sit down and take a survey online, it’s usually because they have something to say,” Via said.

Of the respondents in this survey, 86% were men, 92% were white, 49% had earned master’s degrees and 68% had completed combat deployments. Participants were spread across the U.S., but the highest number of people, about 30%, were located in the Southeast. The Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard and National Guard were represented in the pool of respondents, with the highest concentration — about 37% — serving in the Army. The average length of their military service was 19 years.

A concerning embrace of the Great Replacement

To determine whether disinformation had influenced readers, survey organizers asked for their beliefs about various extremist groups and prominent conspiracy theories. While most respondents reject key tenets of QAnon and the Great Replacement theory, those who do agree still amounted to a “disturbing” number, said Freddy Cruz, a researcher with the nonprofit Western States Center, a nonprofit that monitors political extremism in the U.S.

The Great Replacement theory is a baseless idea that lenient immigration policies are being designed to replace the power and culture of white people in the U.S. The survey asked respondents how strongly they agree or disagree with the notion that a group of people in the U.S. is trying to replace native-born Americans with immigrants and people of color who share their political views.

While 1,770 people completely or mostly disagree with that notion, 438 respondents, or 18%, said they mostly agree, and 223 people, or 9%, completely agree.

“There seems to be some embrace of the Great Replacement narrative, which has been linked to several violent incidents in the U.S.,” Cruz said. “That’s one of the things that stood out to me as one of the more disturbing aspects of the survey.”

The conspiracy theory went from fringe to mainstream in the past couple of years, as conservative media outlets and some elected officials have amplified the message, Cruz said. The theory fueled racist violence and motivated multiple mass shootings, including the 2022 killing of 10 people in Buffalo, New York, and a shooting in El Paso, Texas, that left 23 people dead in 2019.

A poll organized by the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2022 found that one-third of Americans believe the Great Replacement theory. The findings from Military Times and the University of Alabama were on par with a similar poll conducted by the federally funded think tank RAND Corp. in 2023, which found that 29% of veterans believe it.

“The responses for ‘completely agree’ and ‘mostly agree’ with the Great Replacement theory were extremely high,” said Goldwasser, who has studied militia groups for nearly a decade. “This is a theory that was really created and used by white supremacists, so the idea that it’s moved into the mainstream to the point where Army veterans believe it is alarming.”

When asked about their thoughts on Nazis, 83% of survey respondents indicated they think the group is a threat to national security — a figure that surprised Cruz because of the embrace of the Great Replacement theory.

“In the survey, it looks like people overwhelmingly agree that white supremacy is bad, Nazism is bad, but then there’s a smaller group of people who seem to actually embrace Great Replacement, and it’s a weird discrepancy,” Cruz said. “I think it speaks to the GOP doing an excellent job of dissociating the theory from white supremacist beliefs.”

Another cause for concern was the acceptance of QAnon, Goldwasser said. QAnon is an umbrella term for several conspiracy theories that falsely allege a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles run the world. Only 2% of respondents said they completely agree and 7% mostly agree with the theory, but Goldwasser argued those amounts were concerning based on how the question was posed.

Respondents were asked whether they agreed with the idea that the government, media and financial world in the U.S. were “controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation.”

“The fact that people made it all the way to the end of that sentence and agreed with every single one of those statements is disturbing in the grand scheme of things,” Goldwasser said. “It really got to who the true believers were.”

Other surveys over the past few years have tried to ascertain how many U.S. adults overall believe in the QAnon theories. A poll by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2021 found that 15% believe it, and a poll by Yahoo in 2020 pegged acceptance of the theories at 7%.

Where readers get their information

Respondents turned to local news outlets most for accurate information. About 77% of people said they trust their local news either “a lot” or “some.” However, local news is facing a crisis. About one-fourth of local newspapers in the U.S. have shut down in the past 15 years, creating news deserts and driving more people to social media, where disinformation is rampant, according to research from the Center for Information, Technology and Public Life.

Among the Military Times readers surveyed, 59% trust national news outlets, and 29% of respondents trust the news they received through word of mouth. Social media garnered the least support, with only 14% of people trusting the information they received there. Nearly 50% said they didn’t trust information from social media at all.

The lack of trust in social media surprised Parrott, who expected more people to turn to sites like Facebook, X, YouTube and Instagram for their news. A study from Pew Research Center at the end of 2023 found that 19% of U.S. adults overall often get their news from social media, and 31% sometimes do.

“They were skeptical of news, especially on social media, which I think is really interesting,” Parrott said. “I expected more people to be getting their news there.”

Of the survey respondents who do get their news from social media, they most often turned to Facebook, followed by YouTube and X, the survey found. For people who do get their news on those platforms, Parrott suggested several questions they should try to answer to determine whether information is true, including: Does the person posting have a headshot and actual name? How long has the account been active? What other sources can you consult? Is the source objective or biased? Does the post share information that target a social or political group?

“Who’s the source? Where’d they get the information from? Are they real? Has it been confirmed? These are little things you can check,” Parrott said. “If it elicits strong emotions from you or others, if it’s enraging, that’s a sign you might want to check that out.”

Instead of social media, 53% of respondents said they get their information most often from news websites, followed by 37% who turn to television news the most.

Goldwasser warned that it’s unclear what respondents might’ve meant by “news websites.” Fake news sites have flooded the internet over the past several years and have increased in number since the advent of generative AI, which allows users to quickly create content to post online. NewsGuard, which tracks misinformation, found 725 AI-generated fake news sites in operation as of last month.

“This is something I have seen a number of times in a variety of circumstances, where people think it’s a news website, but actually, that might not be accurate,” Goldwasser said. “I think it evokes almost a sigh of relief, like, ‘OK, they get their news from news websites. That’s great.’ But actually, it might not be quite as great as it sounds.”

The survey asked about 14 news outlets specifically, including a few that skewed conservative or liberal, based on the media bias chart from the media watchdog Ad Fontes. Respondents could indicate either that they trusted the outlet, didn’t trust it or didn’t know how to feel about it.

The outlet with the most outright distrust was Fox News, with 57% of people saying they don’t trust it. About 30% said they do trust Fox News.

The Daily Caller garnered the fewest number of people who said they trusted it. Only 5% of respondents trust its news, while 48% don’t trust it and the rest don’t know how to feel about it.

Army Times, which distributed the survey through its morning newsletter, was predictably the most trusted, with 64% of people responding that they trust news found on the website. CBS followed with about 40% of respondents indicating they trust the outlet. About 27% trust USA Today, 31% trust CNN, 22% trust MSNBC and 37% trust The New York Times.

This story was produced in partnership with Military Veterans in Journalism. Please send tips to MVJ-Tips@militarytimes.com.

Nikki Wentling is a senior editor at Military Times. She's reported on veterans and military communities for nearly a decade and has also covered technology, politics, health care and crime. Her work has earned multiple honors from the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, the Arkansas Associated Press Managing Editors and others.