WASHINGTON — Flying under the cover of darkness in mountainous, unfamiliar terrain was something the Army avoided in early deployments to Afghanistan, where helicopters played a vital role in the fight.

But all that changed with greatly improved night-vision capabilities, more training and better tactics, techniques and procedures. Now the Army prefers to operate in what used to be an impossibly dangerous environment for a helicopter pilot.

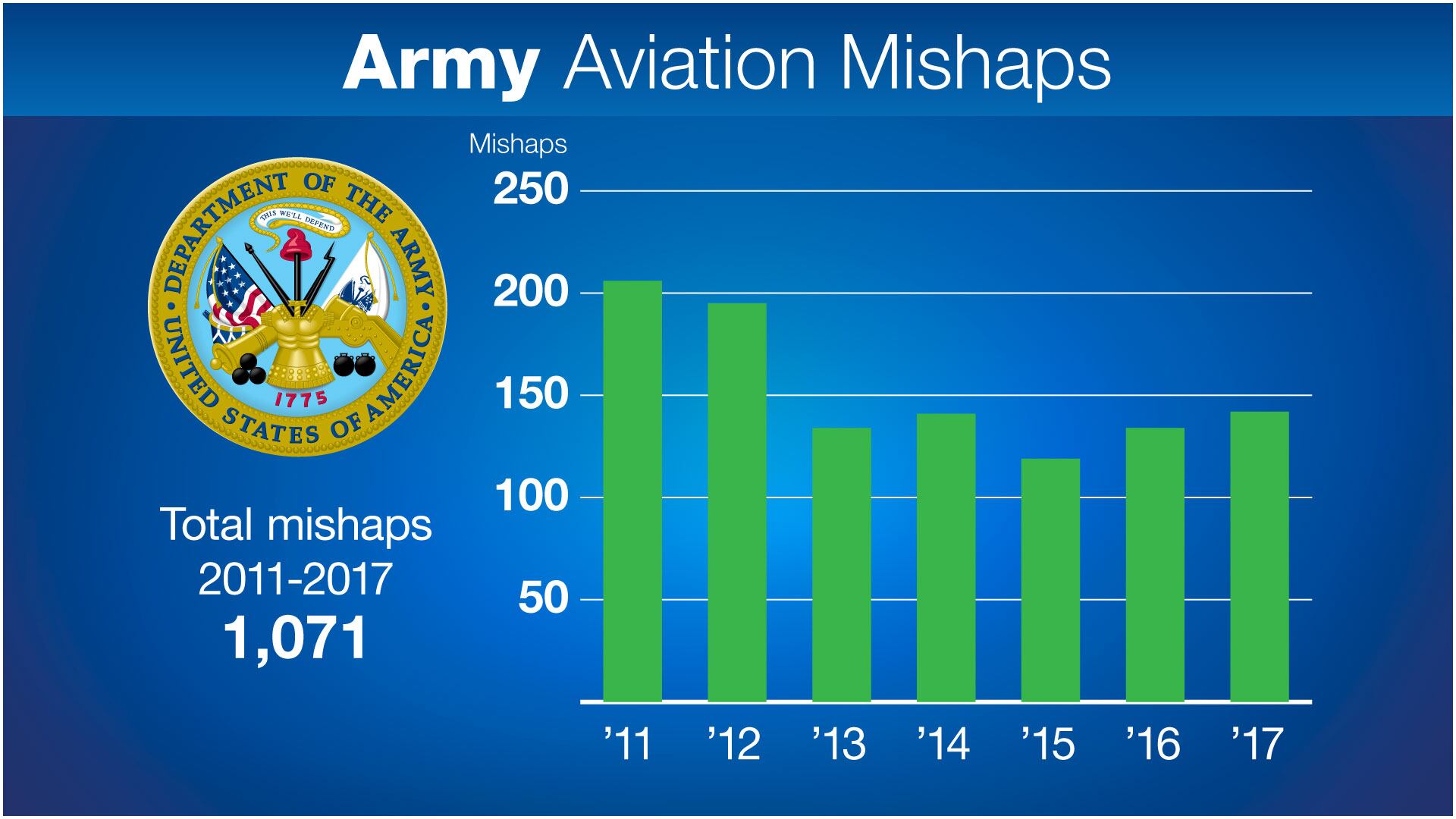

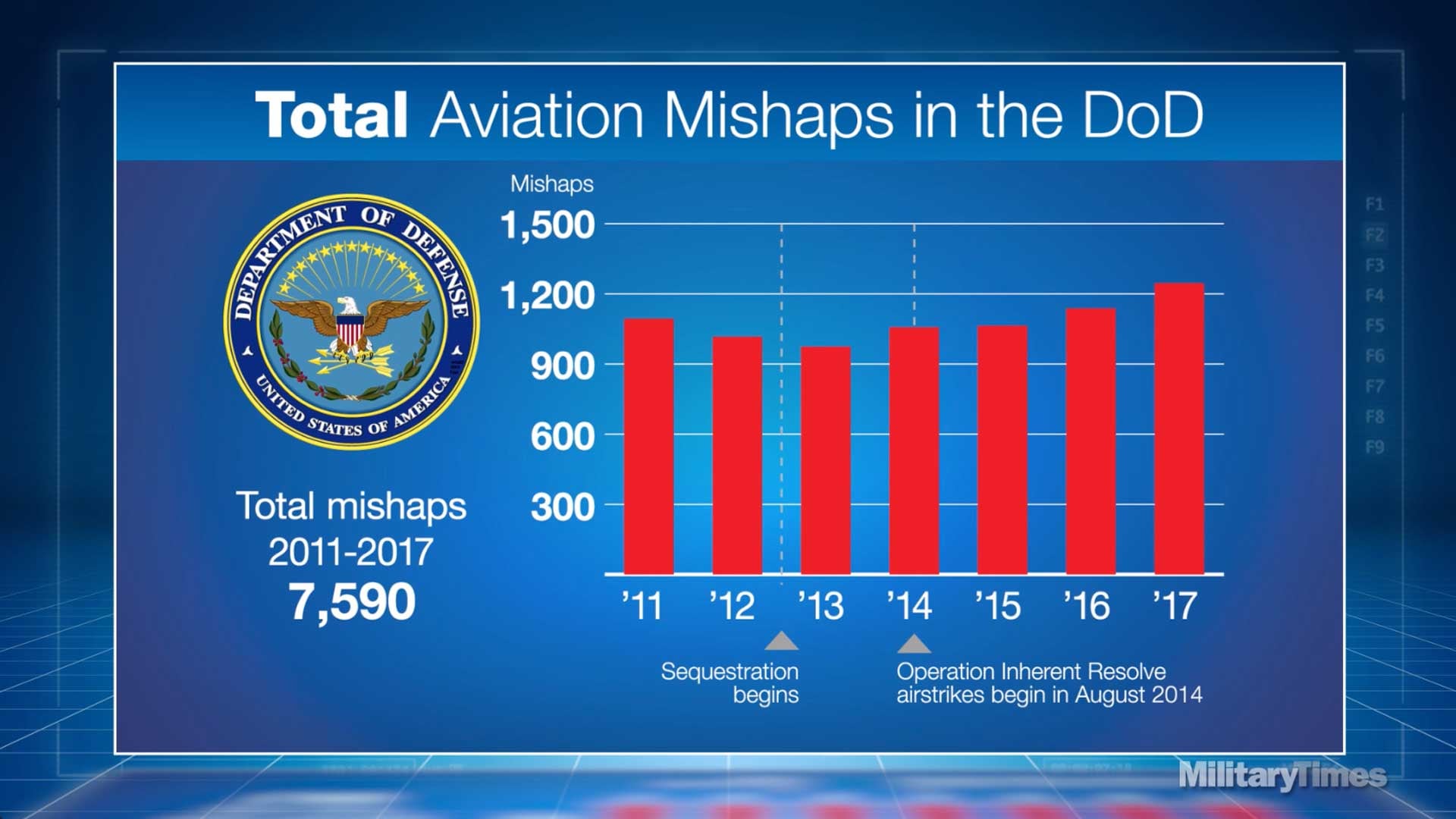

With technological improvements and changes in how the Army manages its pilots and crew, the service has seen the number of aviation accidents in the years following congressional budget cuts — from 2013 to 2017 — hold relatively steady, a significant contrast to the rest of the military’s aviation community where mishaps have steadily climbed in recent years.

RELATED

Army aviation mishaps rose 6 percent during the five year period from 2013 to 2017; and among the Army’s most-used manned rotary aircraft, total mishaps fell slightly, according to a new database of aviation mishaps published by the Military Times.

The accidents in the database range from Class A mishaps — the major accidents involving millions of dollars in damage or that cause fatalities or major injuries — down to more minor incidents that cause minimal damage costing more than $50,000 to repair or resulting in troops missing a day of work, known as Class C mishaps.

The decline in helicopter mishaps does not appear to be directly related to operational tempo changing after the wars in the Middle East shifted course. The Army is busier than ever, flying in Europe and Asia as well as the Middle East to address a wide range of missions.

Military Times and Defense News reviewed data received from a Freedom of Information Act request for details on all military aviation mishaps from 2011 to 2017. The Army experienced a total of 366 mishaps within its helicopter fleet.

Breaking down the numbers

The Army’s worst year in the timeframe was 2012 with 71 mishaps among all major helicopter platforms. The lump sum of accidents were among the UH-60A and L Black Hawk utility helicopters and the AH-64D Apache attack helicopters.

The Alpha-model Black Hawk had 14 accidents, with one Class A mishap. That mishap resulted in a fatality, but had nothing to do with pilot error. A soldier operating in Guatemala was mortally wounded while attempting to film hoist training when a branch broke free from a tree from rotor wash and struck the soldier.

RELATED

The Lima-model experienced 12 accidents with three Class A mishaps. Two of the mishaps were crashes during missions in Afghanistan and in the third mishap, an interpreter was killed when his helmet came into contact with the main rotorblades of the aircraft.

The AH-64 D-model had 14 accidents of which three were Class A. One mishap description indicates human error while the other two indicate mechanical failure. All took place in Afghanistan.

But 2012 wasn’t the worst year for Class A mishaps. A total of 14 class A mishaps took place in 2014. Six of those accidents involved AH-64Ds. Most of those appear to be related to pilot error, including crashes into wooded areas during stateside training flights. One of those crashes involved night-vision training.

RELATED

A couple of years into sequestration, budget cuts and planned troop reductions — 2015 — the Army ‘s relative trend downward was disrupted. The Army experienced 60 crashes, mostly old UH-60 Alphas and Limas, as well as a whopping eight MH-6 Little Bird mishaps. That included 11 Class A mishaps.

The Little Bird is a small helicopter used by special operations forces. Army special operations has wanted to replace the airframe for many years but is now planning on keeping the aircraft until Future Vertical Lift aircraft begin replacing legacy helicopters. A light helicopter likely won’t come online until at least the mid 2030s.

Yet, the MH-6 has experienced only one accident since 2015.

The aircraft that experienced the most accidents over the seven-year period was the AH-64D, with 86 accidents. Of the 86 mishaps, 20 were categorized as Class A. Those mostly had to do with pilot error.

Runner up for most accidents is the UH-60 Alpha-model, with 75 accidents total. Seven of those were class A incidents. The UH-60 Limas also experienced their fair share of accidents with 63 total, of which, nine were class A mishaps.

Also noteworthy is that legacy fleet aircraft lead in mishaps over newer models. The CH-47D Chinook cargo helicopter had 13 accidents in 2011 and eight in 2012 before it was taken out of the fleet. The CH-47F has seen five or fewer accidents from 2011 through 2017.

The AH-64 Echo-model, which is replacing the older Delta-model, has seen only a few accidents each year it’s been flying — since 2014. The Echo-model’s first year was a tough one, with four accidents, two of which were Class A. But since then, it has had only one accident per year. Both accidents in 2015 and 2016 were Class A, including a crash that resulted in two fatalities at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The 2015 accident is unrelated to the aircraft. While in Afghanistan on a reconnaissance mission, a crew fired on Afghan police perceived as hostiles.

And UH-60 Mike-models have an average of four mishaps a year while UH-60L has an average of over seven accidents a year and UH-60A has an average of over 10 per year.

A culture change

The good news is the Army has seen a relatively consistent reduction in accident rates year after year over the last 10 years, Brig. Gen. Frank Tate, told Defense News in a recent interview at the Pentagon.

“There are several large categories and then lots of subtleties as to why we think we have been successful in that regard,” Tate, the director of Army aviation, said.

One of the major changes the Army has made is to codify risk mitigation into mission planning. The Army changed its practices in that regard in 2005 and “you can literally see the difference in our accident rates from when we developed that system and codified it to where we are today, so we feel very confident that has played a big part of it,” he said.

While risk mitigation is a broad term, one primary mitigation, for example, is how the Army now conducts crew selection.

The Army used to use whatever crew was next in line for a mission based on fighter management cycles, according to Tate, but the service realized if it became more flexible and ensured the right crew was in the cockpit for specific missions under specific conditions, the risk would go down exponentially.

“We had to develop a culture where we were literally willing to change crews if need be because we’ve now assessed the risk and what the factors were contributing to that risk and then we say, ‘You know what, that crew is not the right crew for that mission,’” Tate said.

For instance, on a perfect day with perfect weather, when the entire crew has had enough sleep, a crew with less experience can respond to a mission. But if the mission has to be conducted at night or in bad weather and the mission suddenly has more challenging elements to it, it would make more sense to ensure the pilot and crew have more experience.

“If you don’t have a codified process to even identify those risks and consciously have to think through it and apply a crew to it, then you might miss that and then later in the accident investigation you are explaining why you had such a junior crew flying a more challenging mission and it’s not satisfying to say, ‘Well they were on the schedule,’” Tate said.

“The other big risk mitigation is just the basics. Discipline in a unit, high standards in a unit,” Tate said, enforced across the whole formation.

Pilot meetings even down at the company- and battalion-level don’t just focus on taking lessons from accident reports, but from near-misses down in the unit, Tate said.

“If you foster an environment within a unit where you come together in the weekly pilots meeting and those aviators get up and tell their story about how they almost killed themselves and what they could have done differently about it, it helps you develop tactics, techniques and procedures in the unit that is specific to what the unit is doing at that time and what theater they are in and what operations they are on,” Tate said.

Culture has also changed to emphasize that while risk cannot be completely eliminated when it comes to Army aviation, pilots and crew should breed a culture of taking only necessary risk.

“I think we’ve consistently done a better and better job with that,” Tate said. But, he added, “every once in a while you will see a commander put his whole unit down for a day or two because he’s starting to get a feeling that culture’s not right.”

That’s not a bad thing, Tate said, because it’s resetting the unit before it gets too cocky or too confident. That can play a role in a long combat rotation where missions are flown daily. It’s not random that most accidents happen early on or late in a deployment. Either a unit is building experience or they are getting too comfortable at the end, Tate explained.

Dust, mountains and darkness

The Army also aggressively pursued environment training based on a lot of brown-out accidents in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 2000s.

In addition to the dust, Army helicopter pilots also found themselves flying at high altitudes in the mountains of Afghanistan, so the service began sending all of its aviation units to Colorado for high-altitude training, according to Tate.

And when the Army first deployed to Afghanistan in 2001, it was flying helicopters where almost all of them had analogue cockpits “with no systems really to help the pilots outs with these things and their overall situational awareness,” he said.

The one-star added that when first deployed to Afghanistan, they were still using fold maps, “in zero illumination night and you are zipping along through the mountains and you are doing 90 knots with a finger on the map trying to keep track of where you are and at the same time deal with everything else.”

[Army aviation leaders: If we don’t modernize, we risk more crashes, declining readiness]

Now with digital, glass cockpits in the majority of helicopters in the fleet, a pilot’s situational awareness has increased in a more digestible way.

The Army is still working to convert old UH-60L analogue cockpits into UH-60 Victor-models with digital cockpits identical to the M-model.

Systems such as one installed in the CH-47F have allowed the aircraft to essentially land itself in brown-out conditions, which has been a game-changer.

Tate said he believed the Army has experienced only one brown-out Class A accident in an F-model ever. Of the four Class A mishaps in CH-47Fs since 2011, none appear to be related to brown-out or other degraded visual environment conditions.

The Army continues to be dedicated to developing systems that will help offload the burden on the pilot in degraded visual environments, Tate added.

‘Optimally’ manned

As the Army continues to modernize its aviation assets and bring a future family of vertical lift aircraft into the fleet in the 2030s, many of the accidents that still occur could be preventable down the road using artificial intelligence and autonomy.

The Army wants what it’s calling “optimally-manned” aircraft, which keeps a pilot in the loop but removes much of the cognitive burden of flying from the equation, leaving the pilot to focus on the mission.

“Right now the only thing that keeps the aircraft from hitting something in the night is the pilot,” Tate said.

And while many accidents identify pilot error as a cause, it’s not often because the pilot just lacked experience, didn’t train enough or was negligent. There are other factors such as spatial disorientation that can affect even the most seasoned pilots, Tate said.

Spatial disorientation is among the causes of some of the most deadly aviation accidents. A pilot loses his or her proper reference with the earth and what their position is relative to the earth, Tate explained. There are instruments that help to orient the pilot, he added, but they only work “if you look at it.”

But spatial disorientation is “a powerful thing, once your mind has decided that light on a boat on the ocean below you is actually the taillight of another aircraft that you thought you were following and your mind is sure of that, it is extraordinarily difficult to break that mindset,” Tate said. “And it only takes between one and four and five seconds from when you get badly spatially disoriented to when you are crashing.”

The Army is definitely moving torward optimally manned, supervised autonomy and for some missions even full autonomy, Tate said.

While the Army’s Future Vertical Lift aircraft might not have all the capability to prevent a pilot from making a deadly mistake, the Army will gradually plug in capability that will further offload the pilot and will have a huge influence on safety, according to Tate.

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.