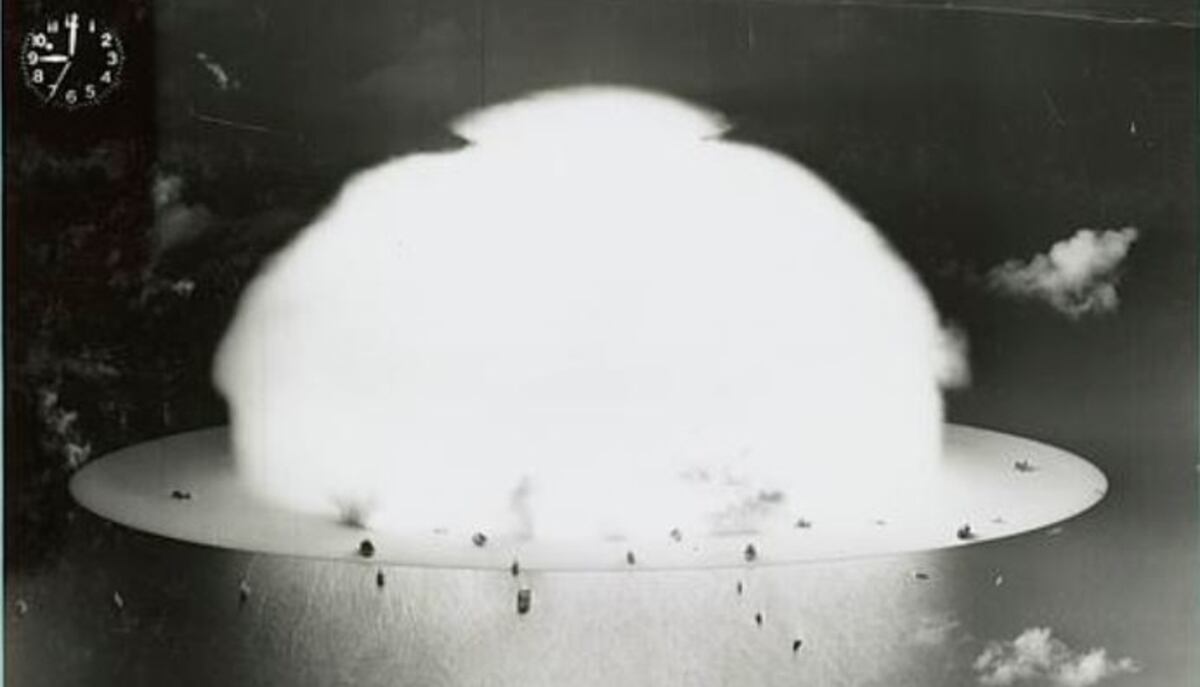

DANVILLE, Va. — First, there was a blinding light. Next came rolling heat and the sight of a mushroom cloud.

It was Nov. 1, 1952, and Junior Jennings had just become a part of history when he participated in Operation Ivy — the United States’ first test of the hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean.

"I was behind a gun turret with my head between my arms with my eyes closed," Jennings, 86, recalled in a written statement. "This blast sent a light brighter than the noonday sun through my arms. I noticed afterward a heatwave came, then they told us we could look at the mushroom cloud."

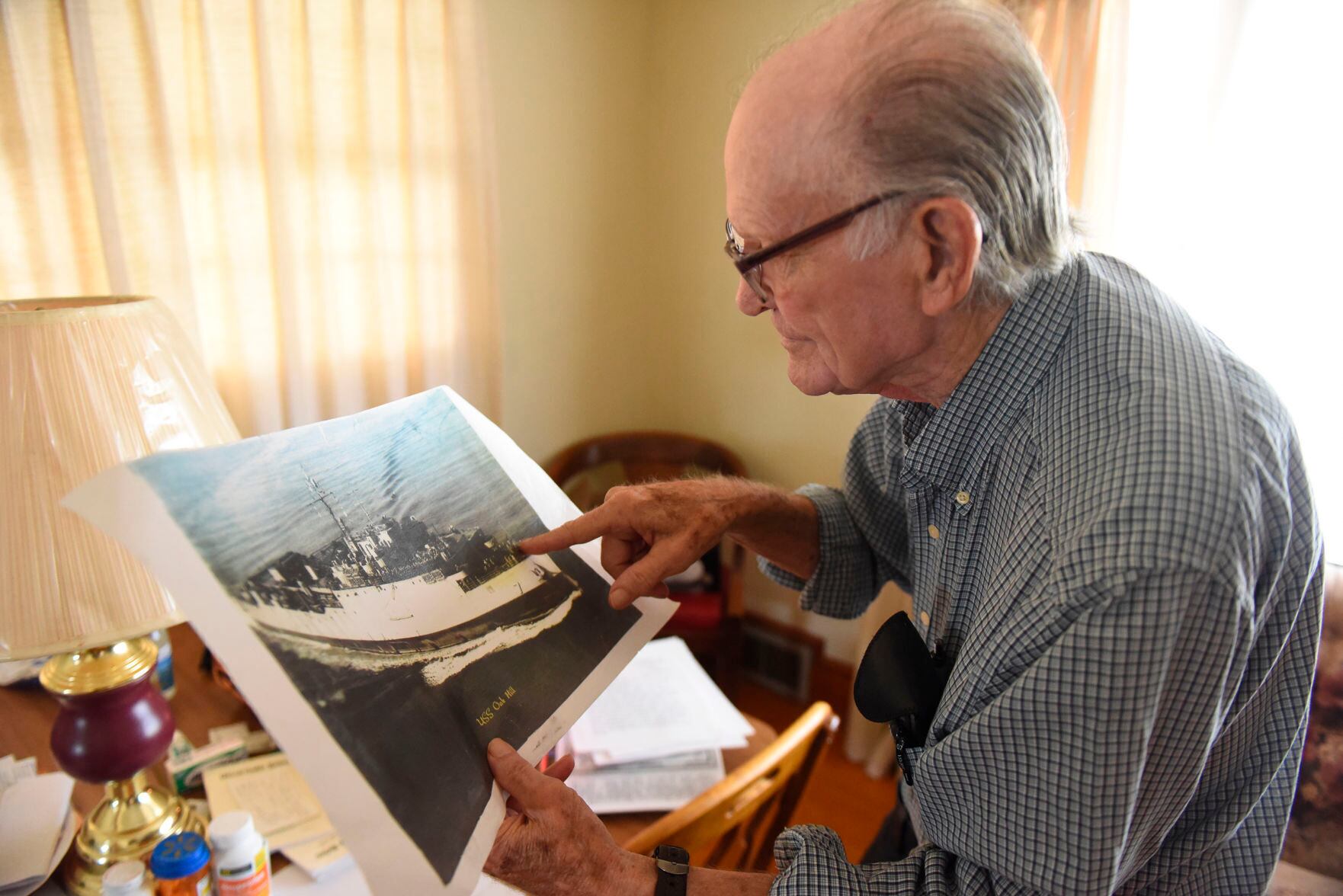

Jennings was in the U.S. Navy, on the Ashland-class dock landing ship Oak Hill, which was named in honor of President James Monroe’s estate in Virginia.

The ship was 15 miles away from the bomb when it was detonated 67 years ago.

"It would have blinded us if we would have looked at it," he said from his Chatham Drive home in Danville.

Jennings was part of a crew of about 200 and their ship was closest to the operation. The scientist who was to set the bomb to go off was on board, he recalled.

"We were the last ship to leave the lagoon at Eniwetok," he wrote. "The scientist went to this island, set the world's first hydrogen bomb to go off, then they returned to our ship."

The hydrogen bomb was developed by Edward Teller, who was part of the Manhattan Project tasked with building the atomic bomb for the Allies during World War II.

Teller, however, wanted a hydrogen “super bomb,” instead.

The test in 1952 provided the U.S. a temporary advantage in the nuclear arms race over what then was the Soviet Union.

Development of the hydrogen bomb accelerated after the Soviet Union’s successful detonation of its own atomic device in September 1949.

The hydrogen bomb was about 1,000 times more powerful than conventional nuclear devices.

Jennings' son, Daniel Jennings, recalled hearing teachers mentioning detonation of the hydrogen bomb when he was in school.

“I’m sitting in the classroom like, ‘Wow, my Dad was there,’” Jennings said at his father’s house on Oct. 23.

Daniel enjoyed hearing about the event from his dad while growing up.

"It's an interesting perspective learning from a first-hand account," he said.

RELATED

Junior’s step-daughter, Sharon Eldridge-Bohannon, said it took a lot of courage for him and everyone on the ship to participate.

"It's something he has never forgotten," she said. "It's nice to have a family member who took part in this historical event."

Junior Jennings, who served on active duty in the Navy from 1951-55 and another four on inactive reserve, joined the Navy instead of the Army because he didn't want to go to Korea.

The Korean War was happening at the time.

"That was the best decision I made," he said at his home. "I'd rather have three warm meals a day."

He got to travel the world during his service, exploring countries including Japan, France and Italy, where he saw Pompeii. He also got to visit Mars Hill — where the Apostle Paul is believed to have preached — in Greece.

"It was amazing," he said of seeing Pompeii, the ancient Roman city buried in volcanic ash when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D.

Jennings returned home and worked at Dan River Inc. for 46 years before retiring in 2002.

Nearly seven decades after that test, Jennings expressed support for our country's development of nuclear weapons.

“We have to defend ourselves,” he said. “We’re sort of bluffing those other nations to keep them from using their bombs.”

RELATED