WASHINGTON and MERSIN, Turkey — A Russian amphibious assault is underway in Ukraine, pushing thousands of Russian naval infantry from the Sea of Azov onto land west of port town Mariupol, according to a U.S. defense official.

It’s a scenario for which Russia has been laying the groundwork for years. Ukraine has been training to defend against such an event since its naval fleet was decimated in 2014 after Russia took Crimea, the peninsula that separates the Sea of Azov from the larger Black Sea.

But an attack from the sea was something Ukraine was particularly vulnerable to — even if Russian forces have so far relied primarily on sending land forces across borders to attack Ukrainian cities.

Wading in

There’s only one way in and out of the Black Sea. Russia regularly sends its ships and submarines in and out of the sea, surging forces there or sending its Black Sea Fleet into the Mediterranean Sea for local operations. Ukraine, unlike Russia, has no other fleets elsewhere, so there’s no backup coming from outside the Black Sea.

Which leads to the question: Who else may come and go from the Black Sea?

Due to Montreux Convention rules regarding the Bosporus and Dardanelles that connect the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, countries that sit on the Black Sea have unlimited access. Nonresident countries may only send ships in for short stints and are limited by ship size. So although NATO is not intervening militarily on Ukraine’s behalf, the Black Sea was always going to be a vulnerable spot for Ukraine.

In other words, if there were ever a body of water well suited for bullying your neighbor, it would be the Black Sea.

Encircling the waterway are Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Georgia and Russia — three NATO members, two who want to join the alliance and then the nation currently invading Ukraine.

That political dynamic was always bound to create tension. But since 2014, the Black Sea has become increasingly strategic and contested. Crimea, located in the northern part of the sea, formerly housed the main hub of Ukraine’s naval force.

Ukraine’s depleted naval force

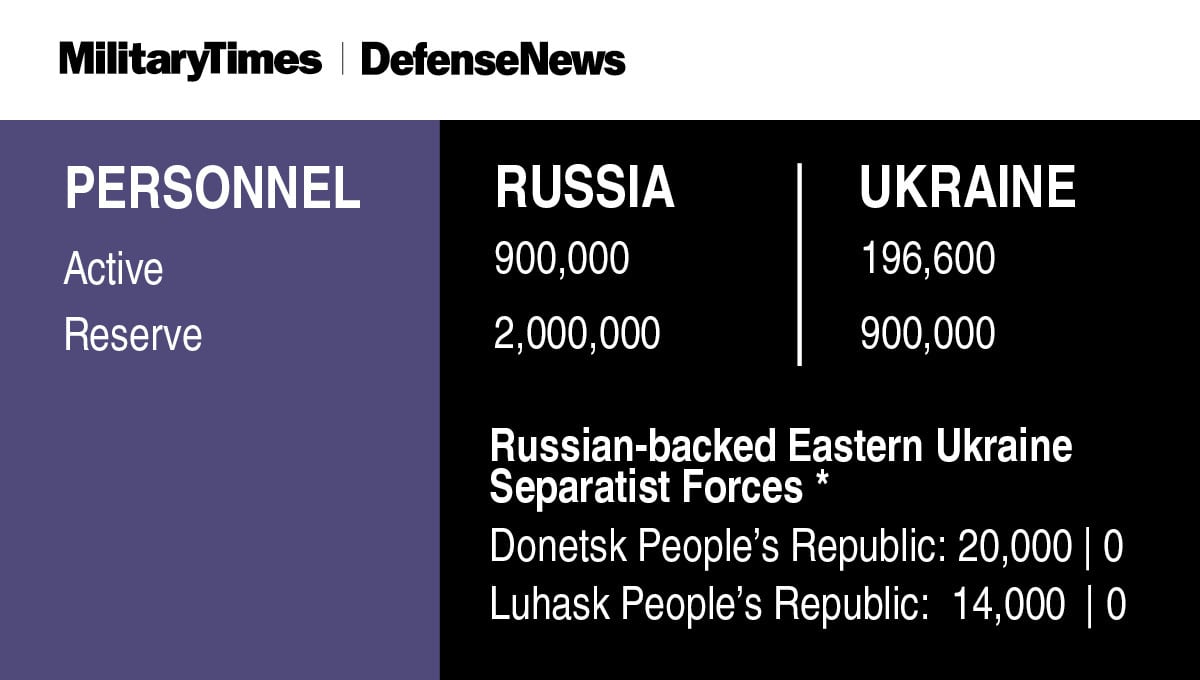

Russia’s annexation of Crimea caused several challenges: first and foremost, about three-quarters of Ukraine’s naval fleet was based there at the Sevastopol Naval Base, and Russia took the ships, their repair yards, helicopters and any sailors willing to fight for Moscow.

Second, it gave Russia control of both sides of the Kerch Strait, which leads from the Black Sea to the Sea of Azov. Ukraine still has legal claims to the Sea of Azov and controls much of the northwestern shores of the sea; but Russia controls land on the east and west sides of the strait, making it easier for the Kremlin to harass, block or take as hostage Ukrainian ships in the area.

And third, it significantly complicated claims to territorial waters within the Black Sea, with the Russian-controlled Crimean Peninsula jutting out into waters that would otherwise be clearly Ukrainian territorial waters under other circumstances.

Last summer, when U.S. Navy destroyer Ross was in the Black Sea for Ukraine-hosted naval exercise Sea Breeze 21, the ship hewed to Ukrainian and international waters only. Defense News embarked on the ship for three days to observe the drills. Despite the ship’s careful course, Russian naval forces near the Crimean Peninsula radioed to the ship — an unusual move in and of itself — to tell Ross to turn around. It was approaching Russian waters, they claimed, and a Russian naval exercise was taking place.

Ross continued its operations, though with three to four Russian ships tailing it at any given time and Russian jets flying overhead.

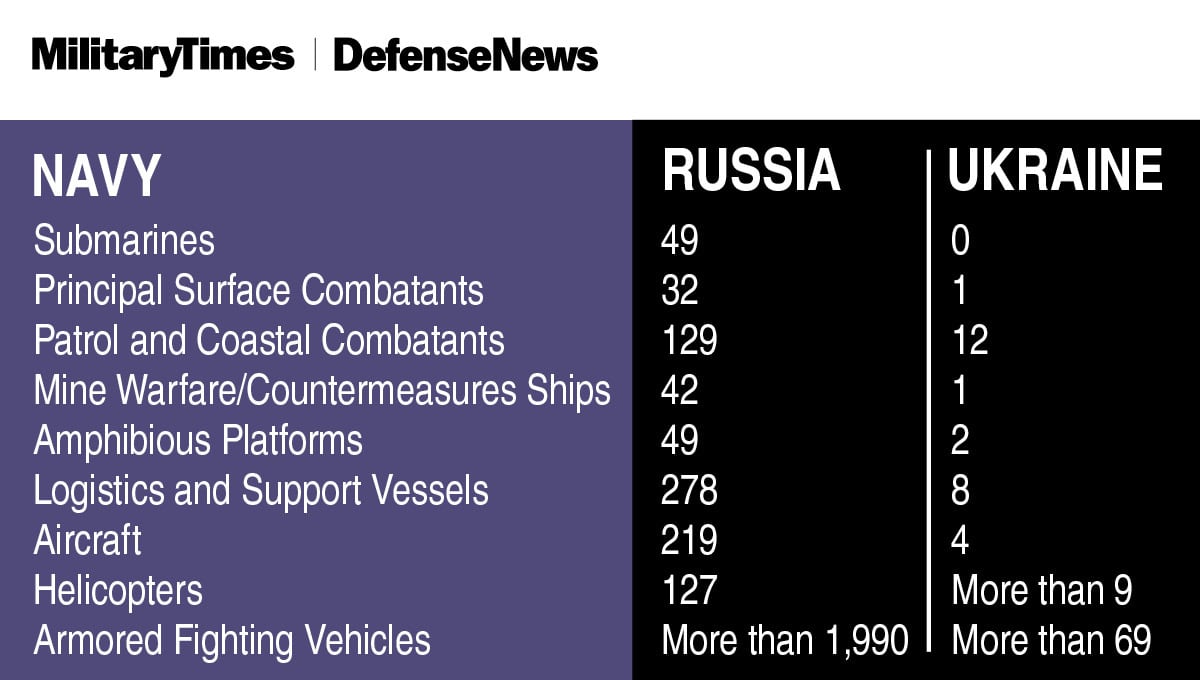

Ukraine has done its best to rebuild its naval power since 2014, though it was left with one frigate as its only “large” warship. It’s taken a “mosquito fleet” approach, trying to build up a number of small vessels that can protect the waters close in to the shore. Eventually, the Navy planned to grow in size and skill set, buying larger ships that could patrol the more open waters of the Black Sea.

While the mosquito fleet patrols close-in waters, alongside the Sea Guard that falls under the State Border Guard Service (akin to the U.S. Coast Guard under the Department of Homeland Security), Russia freely deploys amphibious warships, missile frigates and more throughout the Black Sea.

Ukraine is at both a significant disadvantage and a significant threat right now as it relates to the Black Sea. It lacks the firepower to engage the Russian fleet in any meaningful way. The U.S. Navy and its European partners tried to help Ukraine learn to create maritime domain awareness by netting together sensors; the exercises were still focused on creating a common operating picture shared across at-sea and ashore personnel, not using that picture to pick out and prosecute targets.

Although Russian President Vladimir Putin hasn’t made his final intentions known, Ukraine’s coastal areas seem to have a target on their back. He has already pushed forces from Crimea into the Ukrainian town Kherson. From there, it’s not far across the coast to a naval base in Ochakiv and then onto port city and naval base Odesa. Putin has also pushed forces from the Sea of Azov toward Mariupol — and from there, it would be just a short push northward to connect to Russian forces and Russian-backed fighters in Donetsk and Luhansk.

Pursuing all these lines of effort would connect Russian-held areas in such a way that Putin’s forces could easily resupply themselves from the sea, whereas Ukraine would be cut off from maritime commerce and military opportunities. It would also give him nearly half the Black Sea coastline and allow him to claim significantly more area as territorial waters.

The rules of the sea

Part of Putin’s advantage in the Black Sea is that his ships can come and go as they please, when few other navies have the right or ability to do so.

Ukraine’s ambassador to Turkey asked that the NATO member close the pair of straits to Russian ships to prevent Moscow from bolstering its Black Sea Fleet. Under the Montreux Convention, Turkey manages the movement of commercial and military ships in and out of the Bosporus and Dardanelles.

Turkey said it cannot stop Russian ships accessing the Black Sea due to a clause in the rules that allows vessels to return to their home base, according to Reuters. The country has carefully implemented the Montreux Convention of 1936, which is a critical component of Black Sea security and stability, for more than seven decades. While the convention governs the transit regime across the straits, the most important aspect is defining the principals of military ships transiting the straits and deploying to the Black Sea.

The convention adds to Russia’s advantage there because it prohibits non-Black Sea states’ aircraft carriers and submarines from passing through. Only submarines from bordering, or riparian, states are permitted to pass through the straits, either to rejoin their base in the Black Sea for the first time after construction or purchase, or to be repaired in dockyards outside the Black Sea. However, though Russia has bent these rules in the past to deploy its Black Sea Fleet submarines to Mediterranean waters off Syria and elsewhere.

The Montreux Convention also limits non-riparian states’ naval power in the Black Sea in terms of deployment duration and armada tonnage. Non-riparian states may have a maximum aggregate tonnage of 45,000 tons in the Black Sea. In this regard, one non-riparian state may have a maximum aggregate tonnage of warships in the Black Sea of 30,000 tons. Furthermore, warships from non-riparian countries are not permitted to stay in the Black Sea for more than 21 days.

While the convention generally promotes freedom of navigation through the straits, Turkey retains the right to close the straits to warships from belligerent countries in the event of war or the threat of war. In wartime, Turkey is required by Article 19 of the treaty to close the straits to belligerent warships: “In time of war [v]essels of war belonging to belligerent Powers shall not, however, pass through the Straits except in cases arising out of the application of Article 25.”

Turkey arguably has the authority to close the straits under the principles outlined in the convention. However, there are some political issues. Turkey holds the convention in high regard and has carefully implemented regime rules because it regards the convention as an important component of the security and stability of the Black Sea.

As a result, if Turkey agreed to Ukraine’s request, Russia could make requests of its own, or even accuse Turkey of breaching its neutrality and retaliate.

According to Reuters, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu argues the country can’t stop Russian warships from coming back to their home base — meaning it could stop Russia from sending ships into the Mediterranean, which is a non-issue right now, but it couldn’t stop Russia from flowing more ships to the Black Sea in the name of sending them back to their home port.

Russia could also further bolster its Black Sea Fleet by sending its Caspian Flotilla through the Don-Volga waterway. That force consists of two frigates and seven corvettes, the majority of which are armed with Kalibr missiles.

Because closing the straits is likely to have little impact on Russian capabilities in the Black Sea but would put Turkey at risk of retaliation, or at least lose the appearance of neutrality, it’s unlikely Turkey will take action under the rules of the Montreux Convention.

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.

Tayfun Ozberk is a Turkey correspondent for Defense News.