WASHINGTON — The day President Joe Biden ordered a Chinese spy balloon shot down, sailors at Naval Expeditionary Combat Command began thinking through their potential involvement in recovering debris.

They didn’t know if the military could successfully shoot down the balloon and, if so, what debris might remain. They didn’t know where it would fall, and they didn’t know what hazards might be present among the wreckage.

But the command had salvage divers and explosive ordnance disposal divers on ready-to-deploy orders, and so those teams began gathering their unmanned underwater drones, remotely operated vehicles and dive gear.

On the evening of Feb. 3, two days after Biden’s order, they deployed south from their home base at Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story in Virginia toward the Carolinas.

The next evening, they were in the water bringing up the first pieces of debris.

The head of the command, Rear Adm. Brad Andros, and the leader of Explosive Ordnance Disposal Group 2, Capt. Chuck Eckhart, spoke to Defense News on Feb. 19, shortly after the recovery effort formally ended. They explained how it took a mine countermeasures team and a salvage diving team to carry out this unusual mission.

‘Nobody had seen this before’

The U.S. Navy’s EOD Group 2 is the explosive hazards clearance group for the Atlantic fleet. Like their EOD counterparts in the joint force, these sailors can operate on land; uniquely, they are also certified to dive, allowing them to search for, identify, and neutralize mines and other hazards in the water and on the seabed.

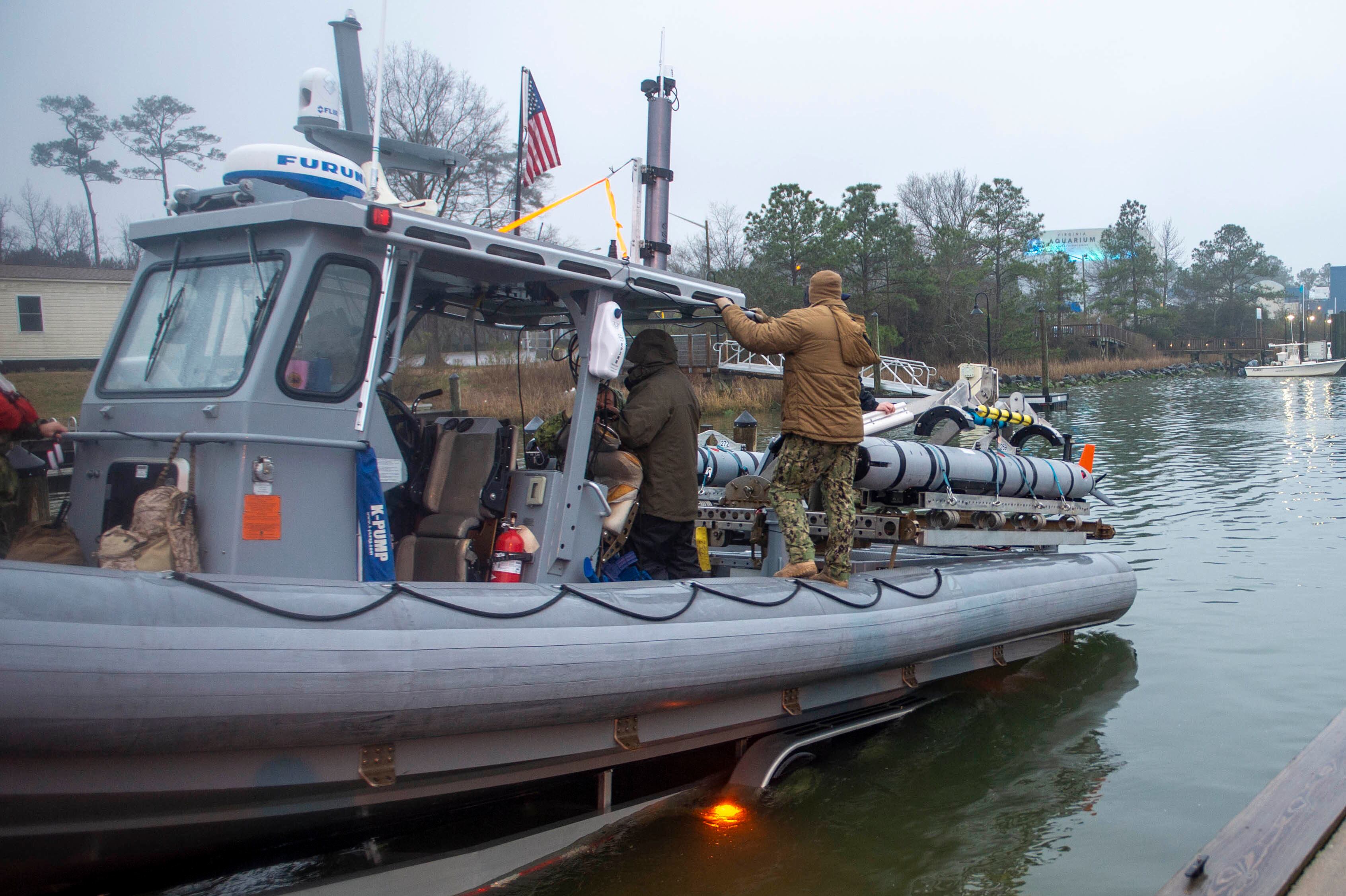

The Navy in recent years has invested in its expeditionary mine countermeasures companies, small organizations within the EOD Groups that conduct mine-hunting clearance operations using divers and unmanned vehicles at sea on small craft.

Also housed within EOD Group 2 is a mobile diving and salvage unit, with divers specifically trained to clear harbors of underwater obstacles or retrieve things like downed aircraft. The team sent on the balloon recovery mission primarily consisted of an expeditionary mine countermeasures company from EOD Mobile Unit 2, as well as a command-and-control element from Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2. They received assistance from MH-53 aircraft from Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 15.

Though expeditionary mine countermeasures divers and salvage divers typically wouldn’t work together, Andros and Eckhart said this mission required both sets of expertise.

Andros explained that salvage divers typically have a more precise location, such as a latitude and longitude associated with a jet crashing into a body of water.

On the other hand, with mine countermeasures missions, the divers must search and clear a wide area — and with a high degree of certainty they’ve found every single piece of hazardous material, otherwise they’re putting their fellow sailors at risk when ships pass through those waters.

Eckhart said the balloon recovery mission was a mix of both, involving an initial location where a large piece of debris fell, but without the certainty of knowing “if that was the everything. So we started there, then we kind of shifted into mine countermeasures, and then the team did come down and do a salvage op in the middle of a mine countermeasures.”

Tough weather conditions dragged out the mission, with heavy winds and seas pausing dive operations multiple times throughout the two-week effort. Because of shallow waters, bad weather on the surface churned up the seabed and moved around debris.

The team from EOD Group 2 searched an area of about 4 square miles, Eckhart said.

Thankfully, Andros added, the team didn’t have to clear the water to the same level of certainty as they would for a mine-clearance operation. Instead, they searched until the FBI was satisfied it had enough debris to study.

“Unlike other missions, there wasn’t the pressurization of time,” he added, whereas with mine clearance the rest of the fleet cannot proceed with their operations until an area of the water is cleared.

Another key difference in this mission was the uncertainty about what sailors needed to find, Andros and Eckhart said.

“It was an unknown thing. Nobody had seen this before. We couldn’t go to the intelligence community and get very specific” information on what they were searching for, Andros said.

Send in the drones

Eckhart said mission participants found a lot of items on the ocean floor during an initial scan, including what appeared to be a telephone pole. But the team relied on unmanned underwater vehicles’ sonar and video to look for human-made objects, typically something that looked out of place or featured sharp corners.

Naval Expeditionary Combat Command and U.S. Fleet Forces Command — acting in its role as U.S. Naval Forces Northern Command — held daily meetings with the FBI and intelligence officials from several government agencies to review what divers brought up and what more the FBI wanted.

“As we handed things over to the FBI, they would then sync up with this organization and give us the feedback of, ‘Hey, we don’t think that you’re finding the right stuff’ or ‘Hey, thanks, this was the right stuff,’ ” Andros said, noting that information was passed down to Eckhart’s team in the water.

When searching a new area, Eckhart said, the team would first use the Mk 18 Mod 2 Kingfish underwater drone, which weighs about 600 pounds and launches from a rigid-hull inflatable boat. The captain praised the system for its long endurance as well as sonar and video technology.

Based on information from the Kingfish, the team would then send down the Mk 18 Mod 1 Swordfish, a smaller underwater drone that weighs about 150 pounds and can be carried into the water by a couple sailors. Eckhart said this small system is more maneuverable and could get a better look at a specific item of interest.

These two vehicles have been in use for more than two decades, and the Navy is replacing them with newer unmanned underwater vehicles in the small- and medium-size categories.

The team also had a remotely operated underwater vehicle that could take a final look at an item if needed, before divers would go into the water to retrieve it.

What did they discover?

Though the balloon-recovery mission was similar enough to the divers’ typical missions, it was different enough to generate lessons that could guide future training.

The recovery “really took the breadth of our capabilities,” explained Eckhart, adding that in future training “we need to plan a little bit more for the unknown, as we’re using our forces more and more outside of what they’re normally applied to go do.”

Naval Expeditionary Combat Command had already started doing this, first by pairing up its Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 2 and the Seabees’ Underwater Construction Team 1 in Ukraine in 2021. And later that year, the command worked ashore, on the water and undersea during a massive wartime scenario for Large Scale Exercise.

“I like the term that some of my mentors have used: that we’re just good problem-solvers,” Eckhart said. “As soon as we get some information, we can start putting it into our planning, adjust our plan on the fly to be able to go forth and do something.”

Andros said the successful mission off the South Carolina coast “speaks to the agility and the flexibility of the force.”

“If you look at the mission: ‘Hey, we have something that just fell in the sky from tens of thousands of feet, and we had no way of tracking it to give you a specific location, but we can give you a general one. Go in and then go find it,’ " Andros said. “[It’s] analyzing right from the get-go of what we think it looks like as it was falling; to going through and saying these are probably the things we’re looking at and the sizes that we’re looking at; to then finding it and adjusting on the fly.

“It really says a lot about the sailors and how they’ve adapted the technology we have on hand right now.”

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.