NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — The U.S. Navy plans to operate a fleet of crewed and unmanned platforms within the next 10 years — an ambitious timeline that will require the service to quickly develop and mature autonomous systems, while ensuring confidence in the technology.

In the air, for example, the Next Generation Air Dominance family of systems set to replace the Super Hornet fighter fleet will include a combination of the piloted F/A-XX fighter with drones dubbed loyal wingmen. This is something the Navy already budgeted for, even as it’s only barely scratched the surface of testing how a large UAV can interact with the air wing.

Still, the Navy is confident unmanned technology will be central to nearly everything it does in the future, according to Vice Adm. Scott Conn, the deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities. Indeed, the chief of naval operations has called for six D’s — more distance, deception, defense, distribution, delivery and decision advantage — and unmanned can play a role in most or all of those.

Conn told Defense News in an April 4 interview that early operations of large unmanned aircraft, surface systems and underwater vessels will likely be tethered to a manned platform as the Navy learns to trust the technology. A fighter pilot by trade, Conn likened unmanned systems to the smart weapons affixed to fighter jets.

“I’ve carried a lot of them, and I’ve employed a few of them. Not one of them was very smart; they were obedient. They did what they were told,” Conn said at the Navy League’s annual Sea-Air-Space conference.

Similarly with unmanned systems, he added, “how do we assure that those — whether it’s in the air, on the surface or in the subsurface — are going to be obedient in terms of what they’re programmed to do in a complex environment? And until we have a full understanding of that level of obedience, then they’re probably going to be tethered to a ship [or] another aircraft.”

Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday made similar remarks to reporters later that day, discussing the potential use of unmanned vessels for resupplying Marines in the Pacific.

“We do see great potential in leveraging unmanned in a lead/follow-like manner … to sustain a force forward. If you think about what we’re doing in the air with Next Generation [Air Dominance], where you would have a quarterback that would be a manned [tactical aircraft] with unmanned as his or her wingmen, same kind of approach,” Gilday said.

Conn said the Navy views its modernization efforts as a three-FYDP process, referring to the Future Years Defense Program that lays out budget plans five years in advance. In this first FYDP, from fiscal 2024 through fiscal 2028, the Navy is investing in buying and testing unmanned prototypes. In the second FYDP, from FY29 through FY33, the manned-unmanned fleet will become reality.

That means the service needs to modify aircraft carriers now so they can accommodate the MQ-25A Stingray unmanned aerial tanker, which Conn called this decade’s “pathfinder” for the Next Generation Air Dominance drones that will join the air wing.

On the ocean surface, that schedule means the Navy must stress the hull, mechanical and electrical systems on unmanned surface vessel prototypes to ensure they can operate for weeks and months without human intervention. The service must also gain confidence in the sensing and autonomy technology of the USVs through operations in complex environments. And the Navy needs to develop networks, combat systems and payloads to make these USVs operationally effective.

Several leaders at Sea-Air-Space presented updates on key unmanned programs. Here are a few:

Large USV

Gilday outlined a path to award a construction contract on the first Large Unmanned Surface Vehicles in FY25.

“The [capability development document] is being developed right now. It will deliver in ’23, and it actually lays out the specific requirement for LUSV,” he said during a lunchtime speech April 4.

Meanwhile, the Navy is turning to industry to begin tests on engineering plant designs that are reliable enough to operate for a month or more at sea without human intervention.

He told reporters after his speech that “within two months, we’ll be doing land-based engineering testing” at commercial test locations. Rather than wait until the Navy finalizes requirements and selects a vendor to put its design through round-the-clock operations ashore, the service plans to start testing multiple industry offerings now.

Defense News previously reported the Navy would begin industry-led testing even as the service builds a test site at Naval Surface Warfare Center Philadelphia Division in Pennsylvania.

Following a year of testing at these industry sites, the Navy will “decide how we’re going to put that engineering plant together and then make the investment in a land-based test site up in Philly, where we’ll run that engineering plant just like we’ve done with [destroyers], just like we intend to do with frigate[s],” Gilday said.

Gilday noted the service will complete the requirements document by the end of FY23; the land-based testing at commercial sites will begin in the next two months and wrap up in FY24; and the Navy will select an LUSV builder by the end of FY25.

The Medium USV program — for which there are seven prototypes in the water or on contract to be built — will follow behind the LUSV program. As Gilday explained, LUSV is paving the way in maturing the hardware for unmanned vessels and the software for autonomous behavior.

LUSV is to serve as an adjunct magazine, hauling around missiles that a crewed ship could remotely launch. MUSV will carry sensing and non-kinetic weapons payloads.

Even as this programmatic work on LUSV continues, Gilday said, the Navy must also invest in making the Large and Medium vessels operationally useful. He noted the service will experiment with underway refueling, remote firing, and new payloads for surveillance, electronic warfare, anti-submarine warfare and more.

“We’re going to improve our ability to command and control this ocean of things that a manned and unmanned navy brings to the fore,” he added.

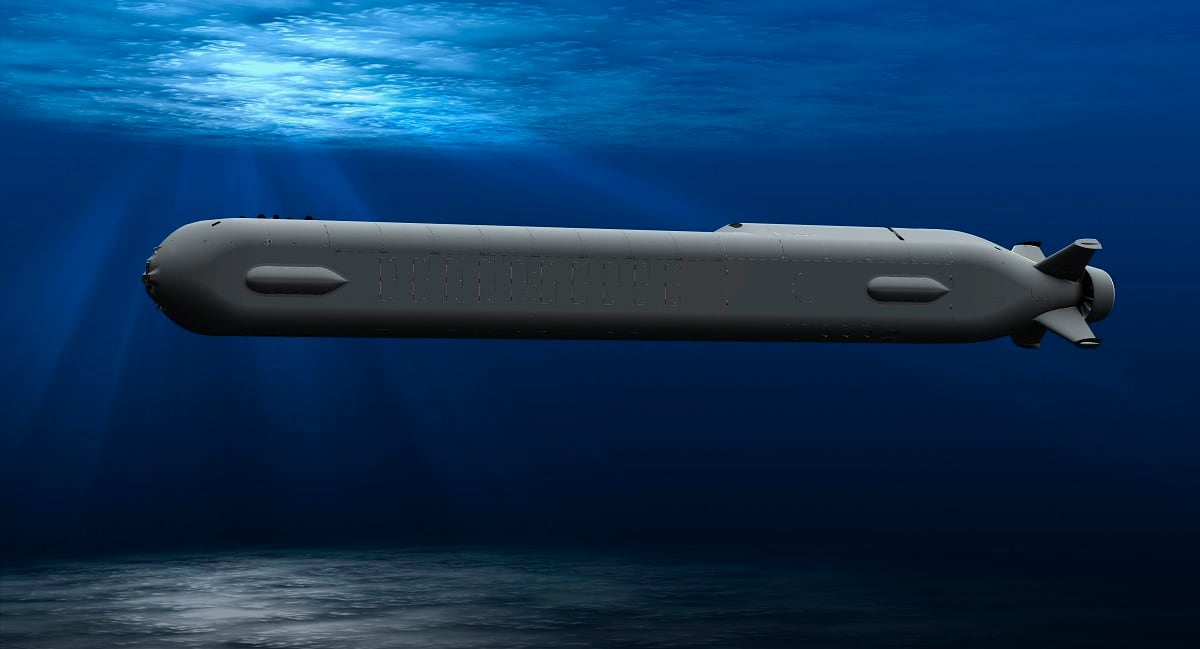

Orca XLUUV

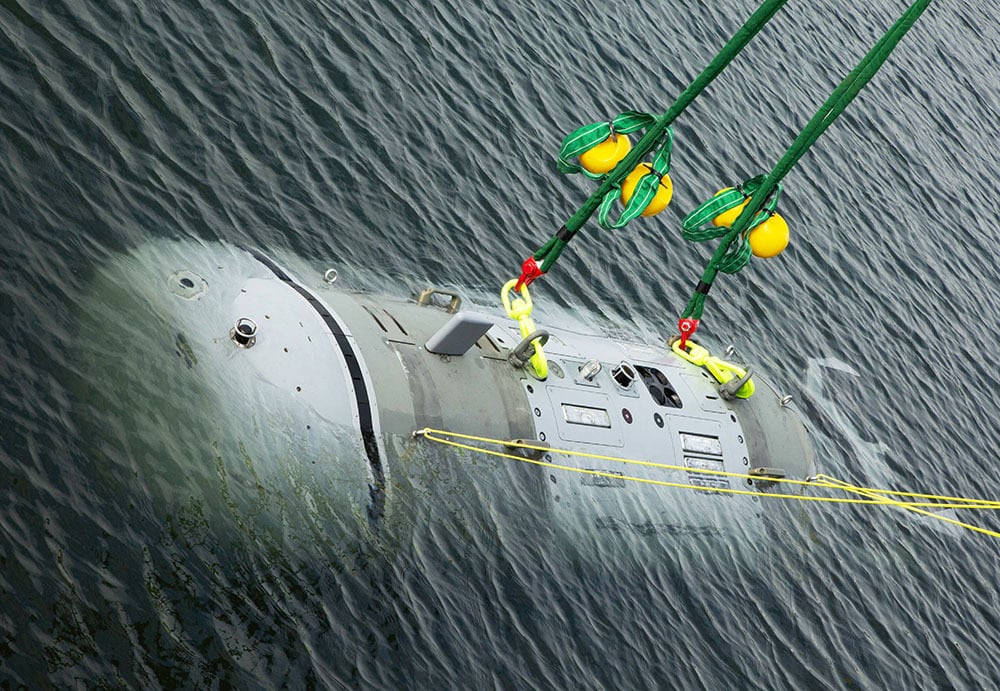

The Navy’s first Extra Large Unmanned Underwater Vehicle hit the water in March for testing, after years of delays to the program.

The Government Accountability Office wrote in a November 2022 report that “the XLUUV effort is at least $242 million or 64 percent over its original cost estimate and at least 3 years late. The contractor originally planned to deliver the first vehicle by December 2020 and all five vehicles by the end of calendar year 2022. The Navy and the contractor are in the process of revising the delivery dates. But both expect the contractor to complete and deliver all five vehicles between February and June 2024.”

Capt. Scot Searles, the unmanned maritime systems program manager at the Program Executive Office Unmanned and Small Combatants, acknowledged it took a while to work through technological and production challenges on what he called a first-of-kind, 85-ton, diesel-electric submarine.

Searles said the tech challenges are solved, though some industrial base and supply chain issues remain.

The first delivered XLUUV, called XLE-0, will serve as a test asset. After hitting the water last month, the “initial results are good,” Searles explained, though he warned testing is still in its nascent stage.

The purpose of this test vehicle is to rapidly “test, fix, test” and allow builder Boeing to insert changes into the five Orcas in production.

“Instead of building it very quickly fives times wrong, let’s go build it once, figure out is it right or is it wrong, figure out how to make it better, and then implement all those changes before you start final assembly” on the five vehicles, he said during an April 4 program update at Sea-Air-Space.

Boeing has about 90% of the material on hand for the five vehicles. The remaining 10% is caught up in supply chain backlogs. Resulting delays “are in the order of about 12 weeks,” Searles said.

Despite delays and ongoing supply chain concerns, Searles said the Navy plans to push an XLUUV forward for operations by FY26.

Snakehead LDUUV

The Navy’s Snakehead Large Displacement Unmanned Undersea Vehicle was all but canceled in FY23, given the service didn’t ask for funding, and Congress didn’t provide it.

Searles said this was due to a decision that made Snakehead less useful in the short term: The LDUUV was supposed to be compatible with the Virginia Payload Module inserted into the Block V Virginia-class submarines, allowing the subs to launch and recover these drones underwater. But that submarine-UUV interface was dropped from the Virginia Payload Module design, Searles added, meaning the Navy’s next chance to pursue it wouldn’t come until the Navy designs and builds its next-generation attack submarine, SSN(X), in the 2030s.

So the Navy nixed Snakehead.

But members of the House and Senate Armed Services committees agreed there was a place for a large UUV in the fleet, and they told the Navy to keep the program hanging by the barest of threads.

“We understand significant advances in commercial technology have occurred since the start of the Snakehead LDUUV program and believe commercially available LDUUVs operated independently from submarines could be rapidly fielded to address current Department of Navy mission needs and capability gaps,” according to a statement accompanying the FY23 National Defense Authorization Act.

The law directed the Navy secretary to conduct analysis and experimentation “with the objective of identifying commercially available LDUUVs that could be fielded as rapidly as possible and deployed at scale as early as fiscal year 2024.”

Searles said Snakehead was revived — sort of. The Navy is now using the last of its FY22 funds to wrap up some experimentation. There was no funding in FY23, but the service did ask for about $7 million in FY24 to continue Snakehead experimentation.

If Congress grants that money, the Navy wants to begin testing Snakehead in deeper waters, having only operated it in shallow waters to date, Searles said.

The captain added that the congressionally mandated market research is underway. As the Navy understands what large UUVs are on the market, it will determine a formal path forward.

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.