This is the second story of a two-part series on how the U.S. submarine force is participating in the trilateral AUKUS alliance. Click here to read the first story.

Australia won’t take possession of its first nuclear-powered submarine until 2032, but Australia and the United States are already training the officers and sailors who will operate that Virginia-class attack boat and the civilians who will maintain it.

“We have eight and a half years to create an Australian [commanding officer] that normally takes 16″ years, said Dan Packer, the director of naval submarine forces for AUKUS.

Given the stakes — the U.S. selling a nuclear-powered boat to another country for the first time, and Australia making its first foray into using nuclear power — Packer said it’s important not to rush the officers’ training and development. It must move forward deliberately, with little down time between at-sea assignments, he noted.

Australia has eight officers in the inaugural training cohort that began in 2023. Three of those eight will be moved into an accelerated training pipeline, and one will eventually be the first Australian Virginia-class commanding officer — though the navies don’t yet want to decide who that will be, Packer said during an April 4 embark aboard the Virginia-class sub Delaware.

“They’re going to finish the pipeline this year. And then they’re going to go to their first boat for a two-year tour,” he said. Next, “we’re going to take them back to Groton, [Connecticut], to go back to department head school, and then they’re going to go right back to another boat. Normally, people do a sea/shore rotation,” but shore tours have been largely eliminated from the accelerated training pipeline.

These three officers will then do a two-year tour in Australia, attend the Australian and American command courses — and then, in 2032, one will be the commanding officer of the submarine that will sail from the U.S. to Australia, lower its American flag, raise an Australian flag and become the lead ship in a sovereign Australian nuclear-powered fleet.

“Right now, the Australian submarine force is about 800 people. We’re going to build it to 3,000,” Packer said. “We understand exactly how many people we need to ingest [into the American training pipeline]. This year, we’re going to ingest 17 officers, 37 nuclear enlisted and 50 non-nuclear enlisted. And we’re going to up that number every year.”

Packer said the impressive part of this training plan isn’t its quantity. It’s the fact that these sailors and officers will be fully integrated into American attack submarine crews until such time that Australia can stand up its own training pipeline at home.

At some point, he said, the U.S. Navy will have 440 Australians on 25 attack submarines, with each crew including two or three Australian officers, seven nuclear enlisted and nine non-nuclear enlisted sailors.

“This is something that has never happened before,” he said. “We are completely, 100% integrating them into our crew, from a complete and utter perspective. They will do everything that we do” while operating aboard the subs.

Short-term wins in a long-term effort

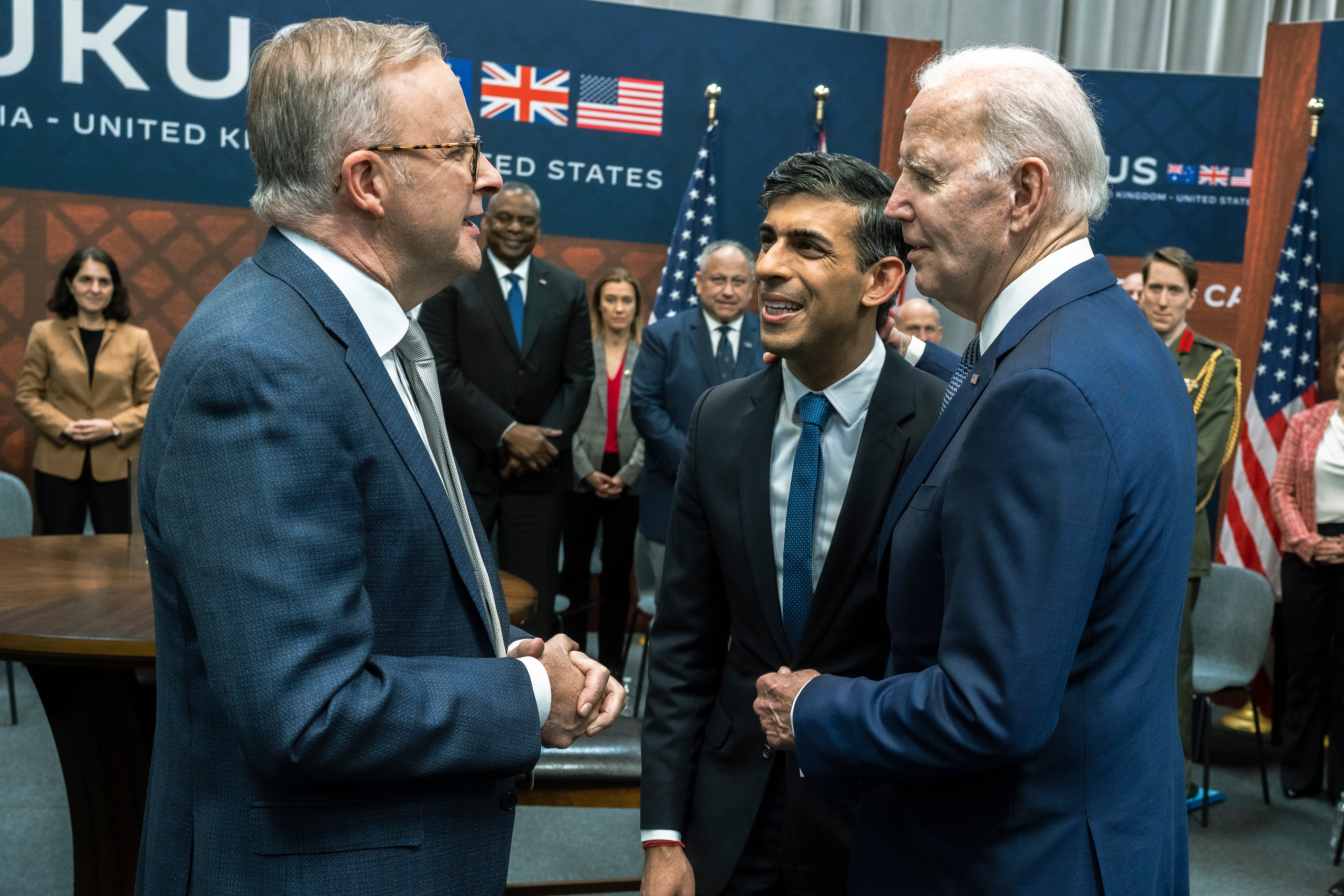

Training the uniformed personnel is just one piece of a flurry of industrial, legislative and acquisition activity that’s taken place since the AUKUS three-phase plan was laid out in March 2023.

Leaders cautioned patience during a recent panel discussion, saying that three countries with separate legislative and budgetary processes were all trying to work in parallel to lay the foundation for a successful trilateral submarine alliance.

“It’s very easy to get dragged down to the short term. But these are long-term goals,” U.K. Royal Navy Second Sea Lord Vice Adm. Martin Connell said.

He added that the upcoming AUKUS milestones can’t wait until all the money and authorities are in place; “we’ve got to move sensibly” and accomplish anything that can be done now, while the rest moves through legislative bodies and budgetary processes.

For example, in industry, “you can see components that are going to go into SSN-AUKUS” in the late 2030s, he said, referring to the attack submarine design both the U.K. and Australia will build.

Australian Defence Industry Minister Pat Conroy added during the panel that his country already committed to spend AU$4.7 billion (U.S. $3.1 billion) to reduce the backlog at Rolls-Royce’s factory, which builds nuclear power plants.

“When people get frustrated, I say there are already parts being produced now for a submarine that won’t be in the water [until] 2042. And I think the budget and the wills of the governments are there; we’ve just got to, in a steady and methodical way, deliver on them,” he said.

There are several more items that were accomplished in the past year:

- In December, the U.S. and Australia finalized a Foreign Military Sales case to procure submarine training devices, including simulators, to support the 2027 establishment of Submarine Rotational Force-West in Australia’s HMAS Stirling base. According to an April joint statement, the first trainers were put on contract in April. The systems will support American sailors assigned to the rotational force and Australian sailors learning to operate the Virginia-class boats ahead of the 2032 sale.

- The U.S. Congress passed several vital measures in the fiscal 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, including the AUKUS Submarine Transfer Authorization Act allowing the sale of boats to Australia. Australia, too, took some important legislative steps: The Australian Naval Nuclear Power Safety Bill 2023 and Australian Naval Nuclear Power Safety (Transitional Provisions) Bill 2023 were introduced to the Australian Parliament in November but have not yet been passed.

- In March, the first group of 20 Australian industry personnel completed a three-month training placement at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Hawaii.

- In January, 37 Australian sailors reported to American submarine tender Emory S. Land in Guam to prepare for the ship’s deployment to HMAS Stirling — where this summer it will conduct a first maintenance availability on an American sub with a combined American and Australian maintenance team.

- Even though U.S. President Joe Biden gave the order to sell nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, there’s still been some heartburn about second-order effects, Packer said, including the need to give Australia the accompanying “cryptographic equipment or electronic warfare libraries or targeting data or even bathymetry.” Packer and his team have been working with other government agencies to pave the way to share these sensitive items and information with Australia, such that they can fully use the submarines they’ll buy and receive next decade.

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.