CARACAS, Venezuela — President Donald Trump’s talk of a “military option” in Venezuela risks alienating Latin American nations that overcame their reluctance to work with the Republican leader and had adopted a common, confrontational approach aimed at isolating President Nicolas Maduro’s embattled government.

Well before Maduro himself responded, governments in Latin America with a long memory of U.S. interventions were quick to express alarm over what sounded to them like saber-rattling. Even Colombia — Washington’s staunchest ally in the region — condemned any “military measures and the use of force” that encroach on Venezuela’s sovereignty.

Maduro has long accused Washington of having military designs on Venezuela and specifically its vast oil reserves, the world’s largest. But those claims were dismissed by many as an attempt to distract from his government’s failures to curb problems such as widespread shortages, spiraling inflation and one of the world’s worst homicide rates.

“For years he’s been saying the U.S. is preparing an invasion, and everyone laughed. But now the claim has been validated,” said Mark Feierstein, who served as President Barack Obama’s top national security adviser on Latin America. “It’s hard to imagine a more damaging thing for Trump to say.”

The timing of Trump’s remarks could not be worse, coming on the eve of a four-nation Latin America trip by Vice President Mike Pence intended to showcase how Washington and regional partners can work together to promote democracy in the hemisphere.

This week in Peru, foreign ministers from 12 Western Hemisphere nations condemned the breakdown of democracy in Venezuela and refused to recognize a new, pro-government assembly created by Maduro that is charged with rewriting the constitution but is seen by many as an illegitimate power grab.

The United States did not take part in the meeting, a show of deference to countries historically mistrustful of heavy-handed policies out of Washington. Suspicion and resentment linger in many corners of the region, a reflection of years past when U.S. troops did in fact invade parts of Latin America to oust leftist leaders or collect unpaid debts.

Yet a number of leaders, amid prodding from the Trump administration, have lately been overcoming their reluctance to intervene in a neighbor’s internal political affairs after looking the other ways for years on Venezuela.

For the first time, leaders have started using the D-word — dictatorship — to describe Venezuela’s government and have recalled their ambassadors from Caracas in protest. Peru on Friday went so far as to expel Venezuela’s ambassador, and last week the South American trade bloc Mercosur suspended Venezuela for violating the group’s democratic norms.

Even more surprising, with the exception of close ideological allies such as Cuba and Bolivia, no country spoke out against Trump’s decision to slap sanctions on more than 30 Venezuelan officials, including Maduro himself, despite past criticism of similar unilateral actions.

Not even the frustration over Trump’s decision to partially roll back Obama’s opening to Cuba — a diplomatic thaw that was applauded across the region’s political spectrum — or his constant talk of building a border wall to keep out immigrants got in the way of presenting a united front toward Maduro.

But the swift reaction to Trump’s “military” remarks shows there is no appetite in the region for U.S. troops to get involved.

On Saturday the nations of Mercosur, which includes Brazil and Argentina, issued a statement saying “the only acceptable means of promoting democracy are dialogue and diplomacy” and repudiating “violence and any option that implies the use of force.”

RELATED

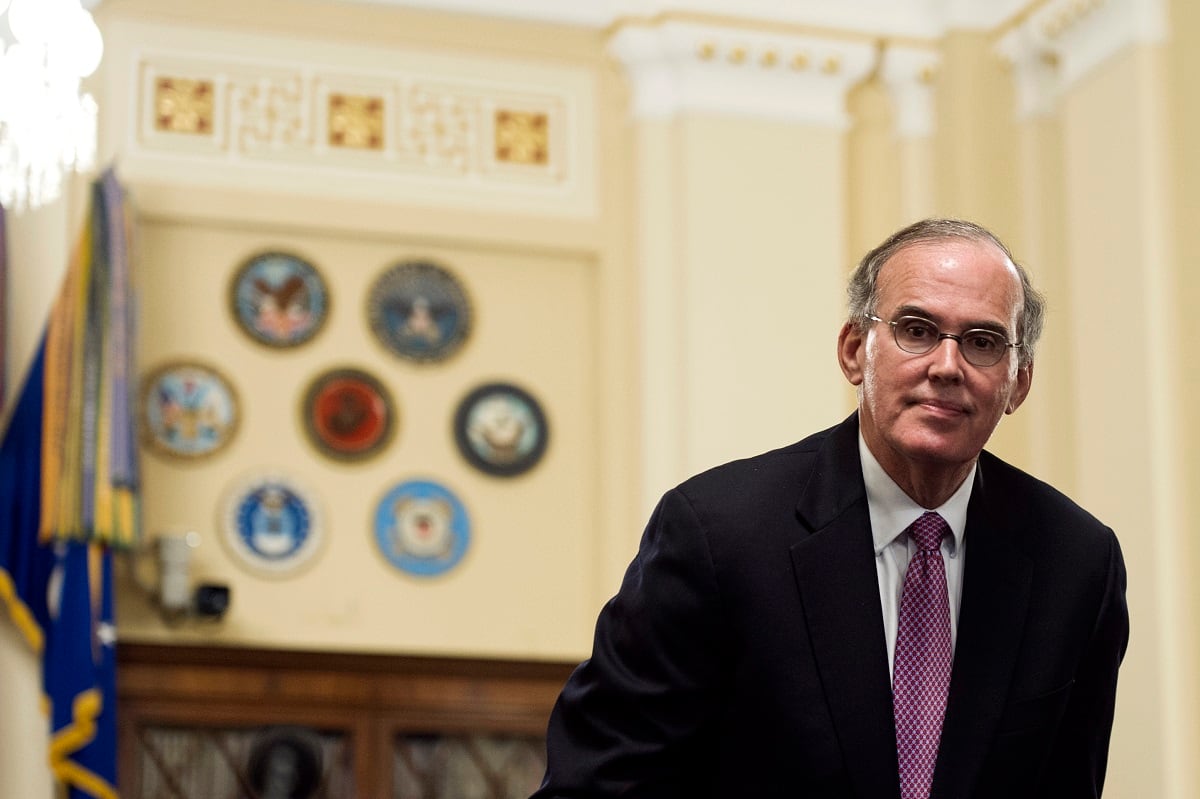

U.S. engagement with other countries has not been constant and may have benefited more from the deteriorating situation in Venezuela than any concerted diplomatic outreach. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson skipped a key meeting of the Organization of American States in June, depriving some Caribbean countries that depend on Venezuelan oil shipments of the political cover they were looking for to abandon their support for Maduro.

Under the advice of Pence and Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio, Trump appears to have taken a personal interest in Venezuela and even met at the White House with the wife of a prominent jailed opposition leader. That in turn has emboldened Maduro opponents who have been protesting for four months demanding he give up power.

Their efforts could be undermined if Maduro expands his crackdown on dissent, arguing as he has in the past that their tactics are a prelude to a U.S.-backed coup. Only this time he can point to Trump’s words as evidence.

Pence arrives in Colombia on Sunday to begin his Latin America tour, during which discussions on how to deal with Venezuela were expected to feature prominently. Instead he may now be forced to do damage control, said Christopher Sabatini, executive director of Global Americans, a website focused on U.S. policy in the region.

“He’s about to get an earful,” Sabatini said. “The eagerness of Trump and some people around him to mouth off without any idea of context is really damaging not only to U.S. policy but also regional stability.