WASHINGTON — When he pulled the plug on the American war in Afghanistan, President Joe Biden said the reasons for staying, 10 years after the death of al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden, had become “increasingly unclear.” Now that a final departure is in sight, questions about clarity have shifted to Biden’s post-withdrawal plan.

What would the United States do, for example, if the Taliban took advantage of the U.S. military departure by seizing power? And, can the United States and the international community, through diplomacy and financial aid alone, prevent a worsening of the instability in Afghanistan that kept American and coalition troops there for two decades?

RELATED

The Biden administration acknowledges that a full U.S. troop withdrawal is not without risks, but it argues that waiting for a better time to end U.S. involvement in the war is a recipe for never leaving, while extremist threats fester elsewhere.

“We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal, and expecting a different result,” Biden said April 14 in announcing that “it’s time to end America’s longest war.”

A look at some of the unanswered questions about Biden’s approach to the withdrawal.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THE TROOPS ARE GONE?

Predictions range from the disastrous to the merely difficult. Officials don’t rule out an intensified civil war that creates a humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan which could spill over to other Central Asian nations, including nuclear-armed Pakistan. A more hopeful scenario is that the Kabul government makes peace with the Taliban insurgents.

RELATED

At a Senate hearing Thursday, a senior Pentagon policy official, David Helvey, was asked how he could remain optimistic when, in just the first few weeks of the U.S. withdrawal, hundreds of Afghans were killed.

“I wouldn’t say that I’m optimistic,” Helvey replied, adding that a peace agreement is still possible.

HOW WILL AFGHAN FORCES HOLD UP?

The administration says it will urge Congress to continue authorizing billions of dollars in aid to the Afghan military and police, and the Pentagon says it is working on ways to provide aircraft maintenance support and advice from afar. Much of that work had been done by U.S. contractors, who are departing along with U.S. troops. The U.S. military also might offer to fly some Afghan security forces to a third country for training.

But none of those things — the training, the advising or the financial backing — are assured.

RELATED

Also unclear is whether the U.S. will provide air power in support of Afghan ground forces from bases outside the country.

The Afghan air force is central to the ongoing conflict, yet it remains dependent on U.S. contractors and technology. The Afghans, for example, have drones but not the kind that are armed, making them less effective in battle.

WILL THE TALIBAN ENLIST OR ASSIST AL-QAIDA?

In a February 2020 agreement with the Trump administration, the Taliban pledged to disavow al-Qaida, but that promise is yet to be tested. This is important in light of the Taliban’s willingness during their years in power in the 1990s to provide haven for bin Laden and his al-Qaida colleagues.

Joseph J. Collins, a retired Army colonel who has studied the U.S. war in Afghanistan since it began, notes that as recently as two years ago the Pentagon was alerting Congress to enduring links between al-Qaida and the Taliban. In a June 2019 report, the Pentagon said al-Qaida and its Pakistan-based affiliate, al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent, “routinely support, train, work, and operate with Taliban fighters and commanders.”

Collins is skeptical that the Taliban have genuinely renounced ties to al-Qaida.

“I don’t think that leopard has changed its spots at all,” he said in an interview.

Earlier this month, the U.S. government watchdog for Afghanistan reported to Congress that al-Qaida relies on the Taliban for protection. The report, citing information provided by the Defense Intelligence Agency in April, said, “the two groups have reinforced ties over the past decades, likely making it difficult for an organizational split to occur.”

WHAT BECOMES OF U.S. COUNTERTERRORIST EFFORTS?

The Pentagon says that all U.S. special operations forces will leave no later than Sept. 11. That will make counterterrorism operations in Afghanistan, including the collecting of intelligence on al-Qaida and other extremist groups, more difficult but not impossible.

The administration’s answer to this problem is to continue the fight from “over the horizon.” This is a concept familiar to the military, whose geographic reach has expanded with the advent of armed drones and other technologies.

RELATED

But will it work? The administration has yet to make any basing or access agreements with countries bordering Afghanistan, such as Uzbekistan. So it might have to rely, at least at the start, on forces positioned in and around the Persian Gulf, meaning response times will be much longer.

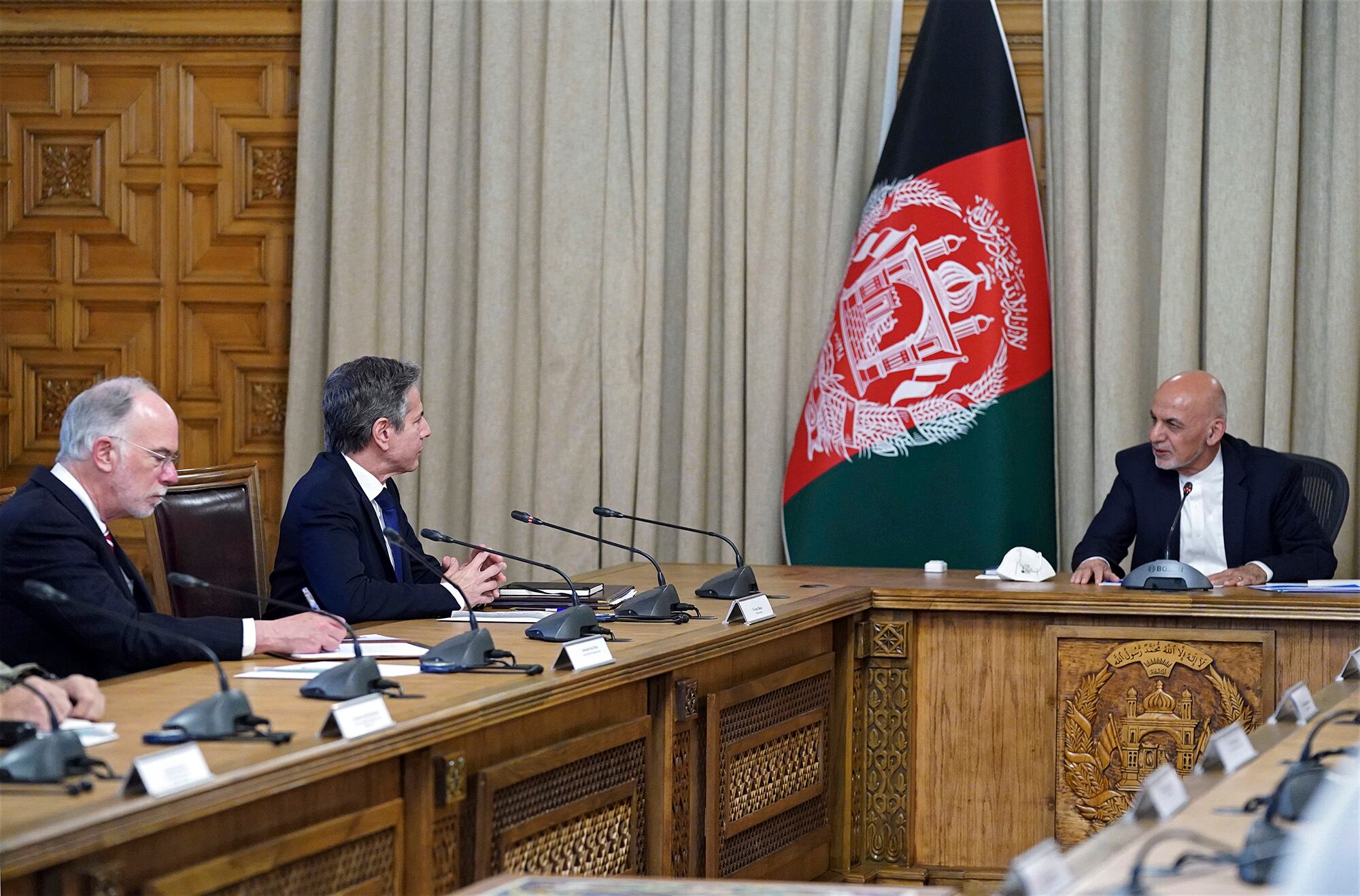

WHAT ABOUT DIPLOMACY?

The administration says it will retain a U.S. Embassy presence, but that will become more difficult if the military’s departure leads to a collapse of Afghan governance.

Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters this past week that securing access to the Kabul international airport will be key to enabling the United States and other nations to maintain embassies. He said the U.S. and NATO allies are considering an international effort to secure that airport.

A related problem is the fate of Afghan civilians who might be targeted by the Taliban or other groups for aiding the U.S. war effort. Interpreters and others who worked for the U.S. government or NATO can get what is known as a special immigrant visa, or SIV, but the application process can take years.

Washington’s special envoy to Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, has told Congress the administration wants to protect those civilians, but that it is trying to avoid the panic that might erupt if it appeared the United States was encouraging “the departure of all educated Afghans” in a way that undermined the morale of Afghan security forces.