SHADDADI, Syria — The Iraqi government is expected to bring home about 100 Iraqi families from a sprawling camp in Syria next week, a first-time move that U.S. officials see as a hopeful sign in a long-frustrated effort to repatriate thousands from a site known as a breeding ground for young insurgents.

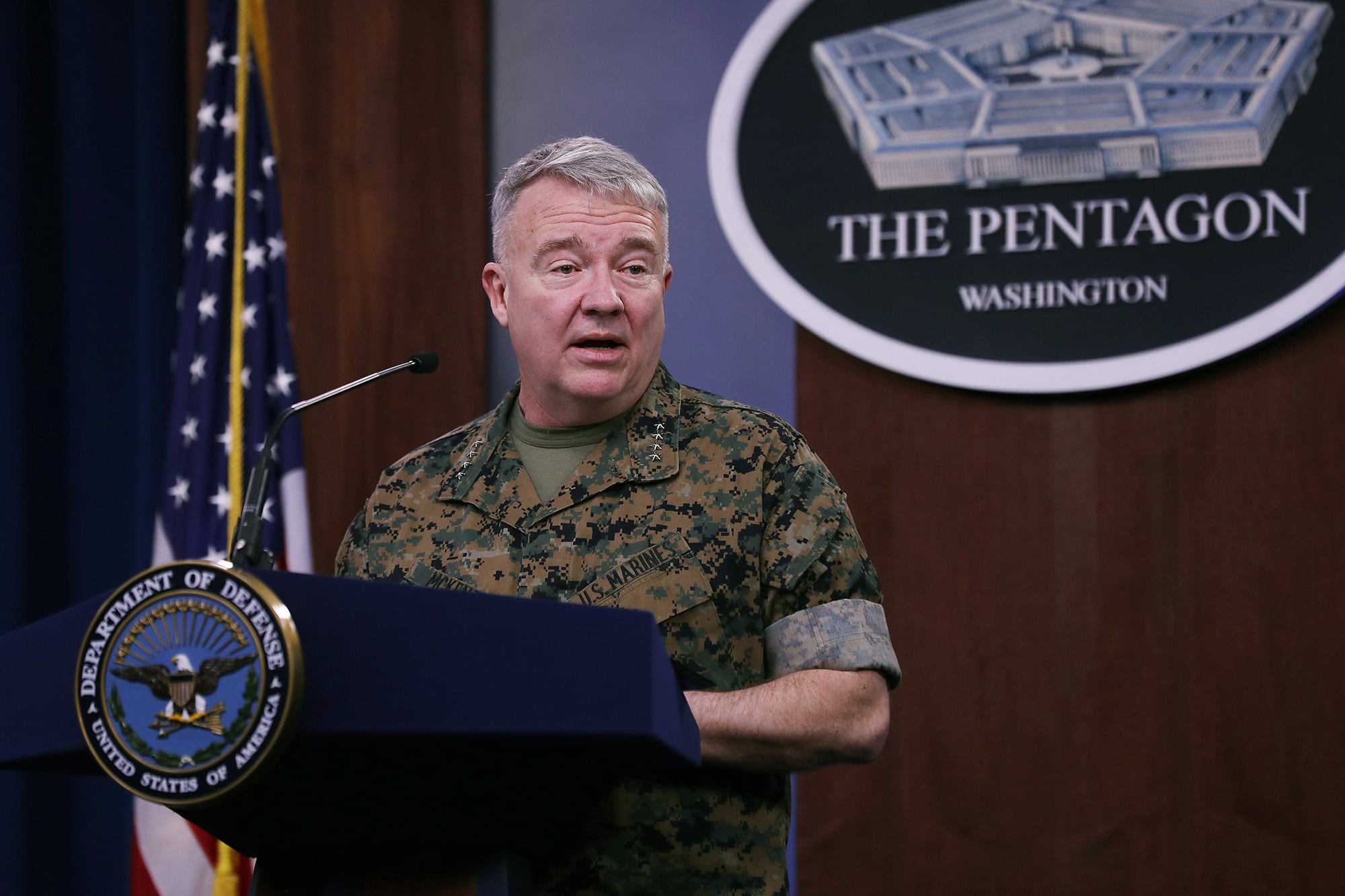

During a visit Friday to Syria, where he met with troops and commanders, the top U.S. general for the Middle East expressed optimism that the transfer from the al-Hol camp will happen. Marine Gen. Frank McKenzie has repeatedly warned that the youth in the camps are being radicalized and will become the next generation of dangerous militants.

“It would be the first step in many such repatriations, and I think that’s going to be the key to bringing down the population in the al-Hol camp, and indeed in other camps across the region,” McKenzie told reporters traveling with him, “Nations need to bring back their citizens, repatriate them, reintegrate them, deradicalize them when necessary and make them productive elements of society.”

RELATED

A U.S. official said the transfer of people from the camp in northeast Syria is one of a number of issues the U.S. and Iraqi governments are discussing as they work out a road map for future diplomatic and military relations. The issue came up during meetings on Thursday, when McKenzie stopped in Baghdad, the Iraqi capital. The official was not authorized to public discuss internal deliberations and spoke on condition of anonymity.

Iraqi leaders earlier this year talked about repatriating some of their citizens, but did not follow through. So the plans for next week have been met with a bit of skepticism, and it appeared unclear whether it might be more than a one-time deal.

The al-Hol camp is home to as many as 70,000 people — mostly women and children — who have been displaced by the civil war in Syria and the battle against the Islamic State group. As many as half are Iraqis. About 10,000 foreigners are housed in a secure annex, and many in the camp remain die-hard ISIS supporters.

Many countries have refused to repatriate their citizens who were among those from around the world who came to join ISIS after the extremists declared their caliphate in 2014. The group’s physical hold on territory was ended in 2017, but many countries balk at repatriating their citizens, fearing their links to ISIS.

In late March, the main U.S.-backed Kurdish-led force in northeast Syria conducted a five-day sweep inside al-Hol that was assisted by U.S. forces. At least 125 suspects were arrested.

Since then, McKenzie said, security has gotten better at the camp. But, he added, security has no real impact on the radicalization of the youth there.

“That’s what concerns me,” he said as he stood at a base in northeast Syria, not far from the Turkish border. “The ability of ISIS to reach out, touch these young people and turn them — in a way that unless we can find a way to take it back it’s going to make us pay a steep price down the road.”

As McKenzie crisscrossed eastern Syria, stopping at four U.S. outposts, his message was short and direct: U.S. forces remain in Syria to fight the remnants of ISIS, so the militants can’t regroup. Pockets of ISIS are still active, particularly west of the Euphrates River in vast stretches of ungoverned territory that are controlled by the Syrian government led by President Bashar Assad.

Out there and in the camps, the underlying conditions of poverty and sectarianism that gave rise to ISIS still exist, said British Brig. Gen. Richard Bell, the deputy commanding general for the coalition fight against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, who traveled with McKenzie.

McKenzie said it was important to keep the pressure on ISIS because the militants still have “an aspirational goal to attack the United States homeland. We want to prevent that from happening.”

He spoke to reporters from The Associated Press and ABC News who agreed because of security concerns not to report on the Syria trip until they left the country. As he spoke, a row of M-2 Bradley fighting vehicles were lined up behind him — a reminder of clashes U.S. forces had last year with Russian troops in the north. At the time, McKenzie requested and got more troops and armored vehicles to deter what the U.S. said was Russian aggression against patrols by U.S. and Syrian Democratic Forces.

But he said they also represented America’s continued commitment to the mission in Syria, to assist the SDF in the battle against ISIS.

“Look at the Bradleys behind me, look at the base that we’re sitting in right now,” McKenzie said. “I think it’s a pretty strong testament to our commitment.

Bell said the ongoing coalition commitment is a concern the SDF asks about. The answer, he said, is a political decision for nation’s leaders, but the coalition is in Syria to ensure the enduring defeat of ISIS.

“They are attempting to reconstitute themselves,” Bell said. “Until the last remnants are completely defeated, and that their will is also broken to stop them from trying to come back, then I think there’s going to be requirements to assist our partner forces.”

RELATED

But when asked how long U.S. troops will stay, he quickly says it is up to President Joe Biden.

During his daylong visit, McKenzie met with the SDF commander, Mazloum Abdi, at an undisclosed military base in eastern Syria. In a tweet Saturday, Abdi said they discussed security and economic challenges in the region. He added that “we have received messages about the continued presence of Coalition forces, joint cooperation to combat ISIS & efforts to protect & stabilize the region.”

Biden has ordered a full withdrawal from Afghanistan, but so far has said little about the close to 1,000 U.S. troops in Syria and the roughly 2,500 in Iraq. America’s presence in Syria is part of a global posture review now being done by the Pentagon.