ST. PAUL — For Lee Pao Xiong, the plight of thousands of Afghan interpreters facing an uncertain future as the U.S. war in Afghanistan ends resurrects memories of decades past, when his own family also faced abandonment by erstwhile American military allies and bloody revenge from their countrymen in Laos.

Back in the 1970s, Xiong’s family and countless other Hmong watched U.S. forces depart Southeast Asia after a similarly long and grinding American war in Vietnam that was similarly full of mission creep and dubious promises of progress from military brass and politicians alike in Washington, D.C.

Xiong grew up the son of an artillery captain in the CIA-backed Hmong guerilla force that fought the Laotian “secret war” against communists and the North Vietnamese Army over portions of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a vital supply route for the anti-American Vietcong fighters to the south. The formal U.S. campaign in Vietnam raged across the border to the east.

“Basically, nobody was supposed to be in Laos, but everybody was in Laos,” said Xiong, 55, now the director of the Center for Hmong Studies at St. Paul’s Concordia University.

Before he arrived in Minnesota and raised a family, before he became a professor and the de facto curator of history for the Hmong diaspora, Xiong first encountered Americans as a child in the mountainous jungles of northern Laos.

American helicopters would land on soccer fields near his home and toss the kids candy. U.S. pilots shot over Vietnam sought refuge there as well.

“They were encouraged to fly into Laos so that we would be able to rescue them,” he told Military Times this spring. “If they were shot down in Vietnam, they would be captured by the enemy.”

Xiong’s childhood home was Long Tieng, a CIA-funded military base-slash-town of about 40,000 Hmong, nestled in the mountainous north and also known as “Lima Site 20A.”

Those days were marked by hiding in bunkers when the North Vietnamese attacked, playing with flare parachutes and once stumbling across three dead attackers early one morning as he searched for those flares.

“There was nobody around me and it was all quiet,” he recalled. “I saw that these dead enemies are real.”

But when America finally pulled out of Vietnam in 1975, ending assistance to the Hmong fighters in the process, Xiong’s family faced the same grim and murky future now facing the Afghans who helped U.S. forces during the war there over the past two decades:

What would become of them once their superpowered benefactor was no longer on the ground? Would the American government do right by them and provide a new life in the United States?

“We were being used as pawns…and we lost a lot of people because of that,” Xiong said. “As we look at Afghanistan, it’s the same thing.”

Today, roughly 18,000 Afghans who have worked alongside the American military — mainly as translators — have requested visas to move to the United States. But as those visa requests await a U.S. State Department verdict, these allies in America’s latest long war fear a violent death at the hands of Taliban extremists who have seized increasingly larger chunks of the embattled country.

Marine Corps Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, the head of U.S. Central Command, told Military Times this month that his team has drafted up “workable plans” to evacuate Afghan interpreters if needed.

McKenzie said he has talked with Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin about such contingencies, but that the final decision lies with the State Department and levels above.

“The Department of Defense is prepared to undertake any tasks that we would be required to do in coordination with a presidential decision,” he said.

America’s treatment of local allies who made overseas military campaigns possible came to define the course of Xiong’s younger years.

Similar decisions will — for better or worse — define the lives of many Afghan families in the coming decades as well.

Forty-six years ago in Laos, Xiong’s family faced potential doom. Fortunately for them, they were among the several thousand Hmong airlifted out of Long Tieng in May 1975, part of an impromptu evacuation stood up by a rogue U.S. Air Force officer.

The remaining Hmong allies of America who could not get on those flights, those who were unable to cross the Mekong River and reach sanctuary in Thailand to the west, were killed by Laos’ communist forces, he said.

Tens of thousands died.

The saga of Xiong’s life, his family’s alliance with the United States decades ago and their fraught path to a different world, also offer a reminder of how war and immigration have intertwined in America’s past.

Xiong and his family eventually made their way to Minnesota and have lived and thrived in the Twin Cities ever since, claiming their own square of the immigrant tapestry that characterizes Minneapolis-St. Paul today, a handful of the nearly 200,000 Hmong taken in by the United States, according to the non-profit Migration Policy Institute.

“For Hmong, we’re loyal to America to the end,” Xiong said. “We have children that fought in Iraq, in Kuwait, in Afghanistan, people that died over there. We have children that are a part of that.”

“I assumed that winning the Vietnam War would be no problem.”

If a coup in the Laotian capital of Vientiane hadn’t been successful in 1960, six years before Xiong was born, he might not be a Minnesotan today.

Such is the butterfly effect of American foreign policy.

After the coup, President John F. Kennedy authorized the recruitment of Laos’ ethnic minorities, including the Hmong, to take part in covert operations to stem the spread of communism in southeast Asia.

That same year, a CIA agent named Bill Lair would meet with a young Laotian military officer, Vang Pao, and recruit him to run the anti-communist paramilitary Hmong effort in the country’s mountainous north.

Thus began a clandestine partnership that would span more than a decade and eventually land Xiong in St. Paul.

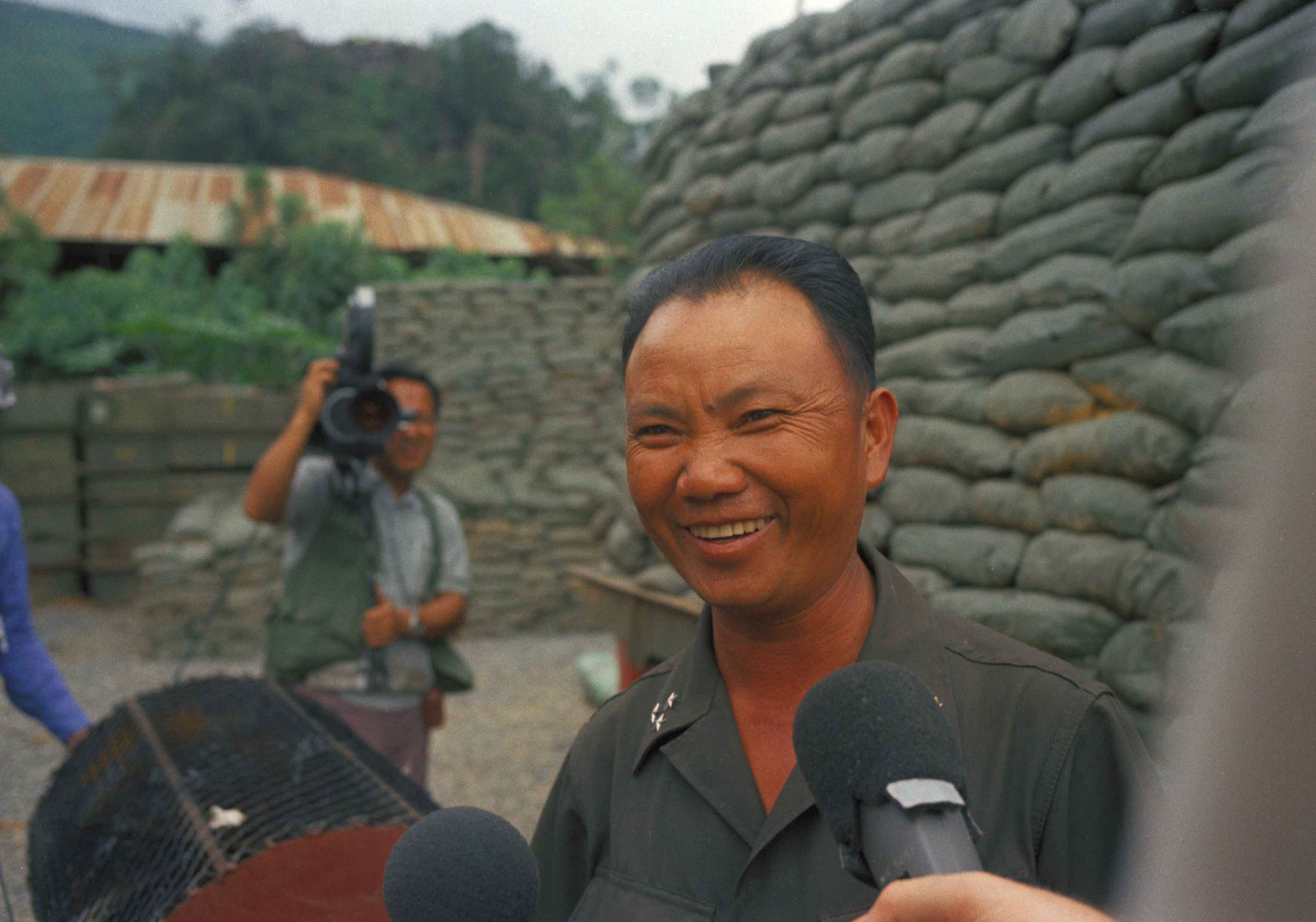

Junior officer Vang Pao would ascend to become Gen. Vang Pao, leader of the Hmong guerilla units that included Xiong’s elders and the future Hmong diaspora in America.

“A sharp increase in the number of Hmong troops, supported by American military and CIA advisers, along with huge drops of military supplies, signaled the start of what is now called the Secret War,” according to an account by the Minnesota Historical Society.

At a press conference in 1961, President Kennedy insisted that Laos was not merely “a Cold War pawn,” and that America wanted peace and stability there.

Communism was “pouring into Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam,” Vang Pao said in a 2006 interview in St. Paul. He allied with America because the mighty country had won two world wars.

“I assumed that winning the Vietnam War would be no problem,” he recalled.

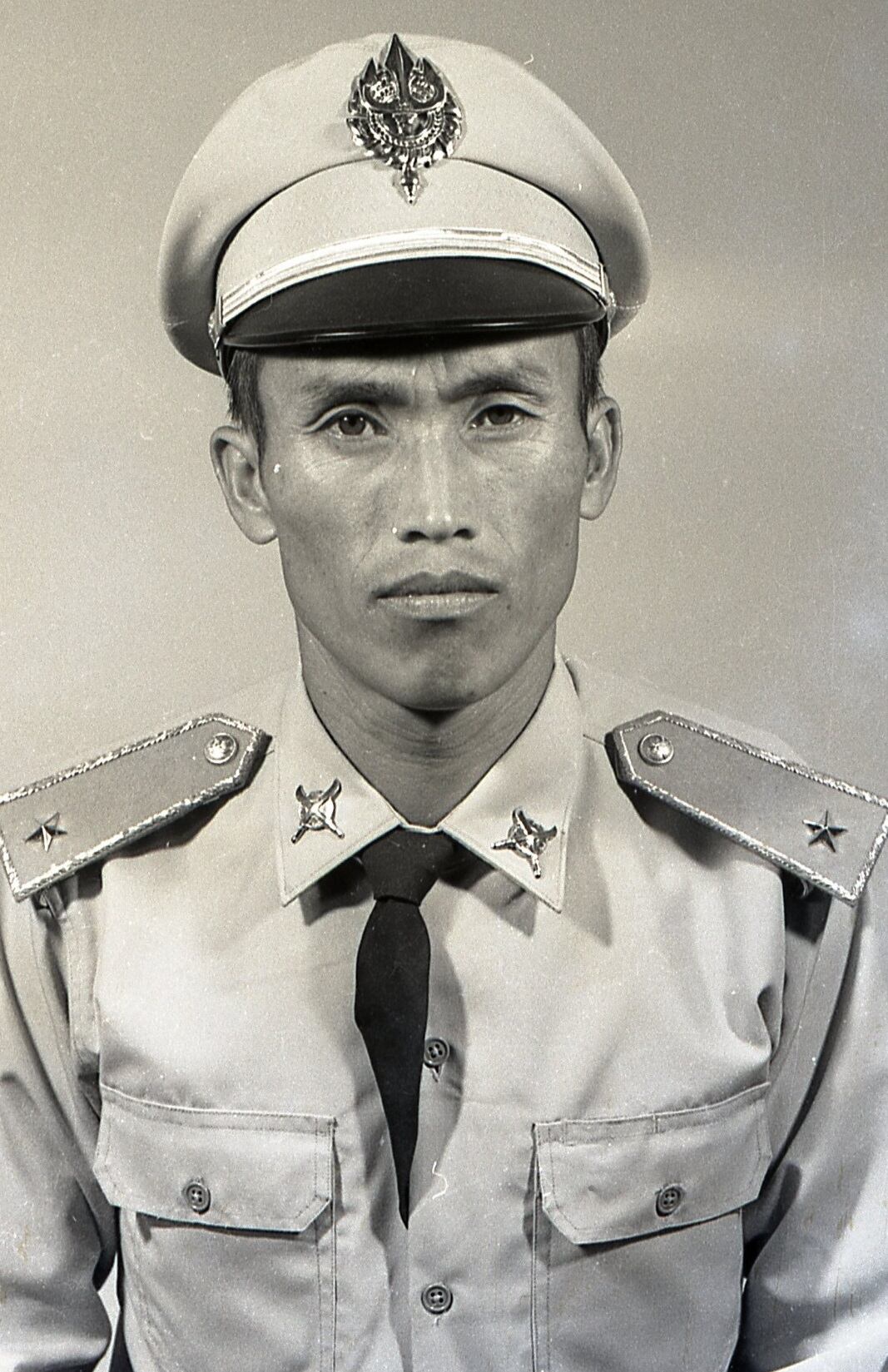

As the Vietnam War boiled to the east that decade, Xiong’s father, Capt. Song Khoua Xiong, a heavy artillery unit commander, and other Hmong fighters battled the North Vietnamese Army over portions of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Capt. Xiong and men like him, armed and funded by the United States, fought several NVA battalions in north Laos, “so that they wouldn’t go down to South Vietnam to fight against the Americans,” Xiong said.

Roughly 35,000 Hmong perished in the fighting, Xiong said.

“If it wasn’t for the Hmong, more than 50,000 Americans would have died as well,” he added.

According to declassified records, 728 Americans died in Laos, most believed to be CIA members.

The U.S. military dropped two million tons of ordnance on the country from 1964 to 1973, and 200,000 Laotians were killed in the war, Harvard Prof. Fredrik Logevall wrote in the Washington Post in 2017.

Another 20,000 Laotians were killed and thousands more maimed by unexploded cluster bombs in the ensuing decades, Logevall wrote.

Shortly after Vang Pao signed on with Lair and the Americans, the CIA helped stand up Long Tieng, where Xiong was born.

Xiong’s first nine years were colored by North Vietnamese attacks, plane crashes and dead bodies.

“They sent [North] Vietnamese commandos in to raid the town,” Xiong said. “Helicopters flying in every day, planes flying every day. Even our toys…we would fashion knives out of those metal straps that they wrap ammunition boxes in.”

But the limestone mountains on three sides of the secret city provided a stout natural defense.

“If you were to fire…(155-millimeter artillery) into the airfield, you’ll hit the side of the mountain,” Xiong said. “If you fire it too far, it will hit the other mountain.”

Hmong pilots flew World War II-era American T-28s from Long Tieng, Xiong recalled. These days, when he hears a plane’s engine rumbling overhead, those childhood memories return.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, I know that sound,’” he said. “That sound is very therapeutic.”

When the 9/11 attacks happened in 2001, Xiong remembered the smell of blood and burning flesh, “because I was at another crash site in Laos.”

“Who will you take?”

After the U.S. military left Vietnam and Saigon fell in 1975, after the communist conquering of nearby Cambodia, Capt. Xiong and the Hmong force’s other soldiers were on edge. The enemy was closing in.

Word spread in May that the Americans were readying evacuation flights for Gen. Vang Pao, other brass and their families.

That effort was largely due to Air Force Brig. Gen. Harry Aderholt, believed to have been the last American general on the ground in Southeast Asia by that time and who led an air commando wing earlier in the war that conducted low-flying raids over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in North Vietnam and Laos.

Xiong reckons he and others in the Hmong diaspora are alive today because of Aderholt, though the role of Aderholt — who died in 2010 — at Long Tieng is not mentioned on his official Air Force biography.

Through the course of his research, Xiong said it appears as if Aderholt largely acted alone and the planes had their U.S. military markings removed.

“When you look at the documents and try to piece history together, you get pissed off,” he said. “The United States had no plan to evacuate the Hmong. It was not a concerted United States effort to evacuate us.”

Aderholt secured a C-130 and two C-46 aircraft for the frantic airlift of Long Tieng over a few days that month, mainly to evacuate Vang Pao and Jerry Daniels, his CIA case officer.

“Basically, Aderholt paid these pilots on their way out,” Xiong said.

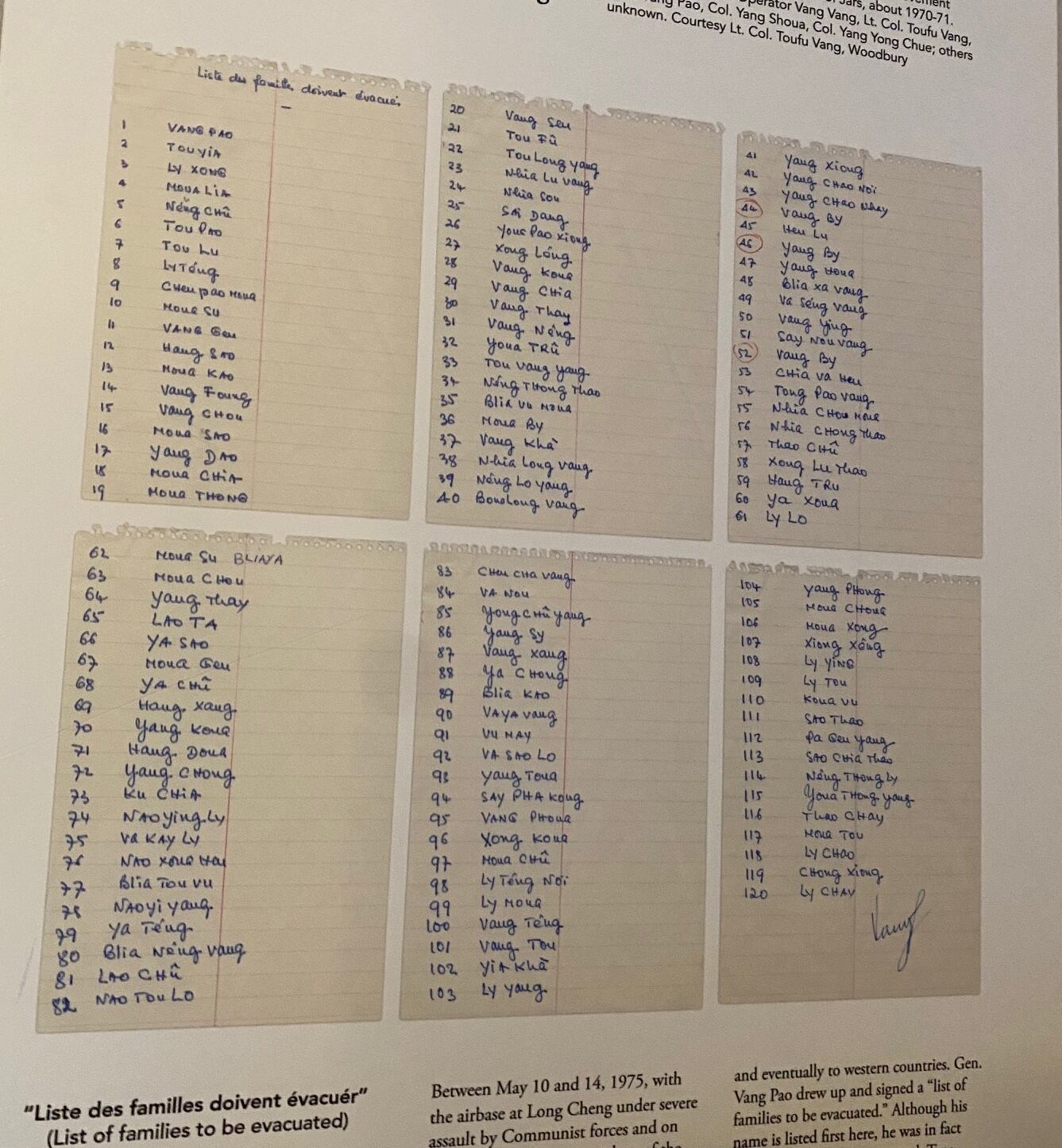

At the Center for Hmong Studies that he oversees in St. Paul, a replica list of Hmong officers cleared to get on those flights hangs on the wall.

Capt. Xiong’s name was not among them, he was too low-ranking, but he was determined to get his family on those birds.

The flights began on May 12.

As colonels and their families drove military trucks onto the American aircraft, the crowd began to realize they didn’t plan to evacuate everybody.

“People realize they’re being tricked,” Xiong recalled.

The mass of Laotians, which Xiong estimates was 5,000 to 10,000, began mobbing every American plane that landed, scrambling to get onboard.

At one point, a colonel drove across the airfield, warning everyone to back up because the North Vietnamese were going to bomb the runway.

Incensed that only high-ranking officers were being allowed to escape on the wings of their onetime benefactors, Capt. Xiong soon made his move.

“My dad pushed my mom, myself, along with two brothers onto the plane,” Xiong said. “He got left behind. We were all packed like sardines.”

They landed at Royal Thai Air Base Nam Phong, which had been used by U.S. Marine Corps aviators during the Vietnam War.

They waited most of the day and Xiong watched his father come off one of the last C-130 flights out.

“It was a very chaotic scene,” Xiong said of the escape from Long Tieng. “But we were able to get out.”

Xiong’s family left on May 13, and Gen. Vang Pao departed the next day.

“When Gen. Vang Pao was evacuated, that was it,” he said.

Who escaped via the sheep-dipped airborne beneficence of Aderholt felt like a cruel calculus.

Those left behind were furious, Xiong added, and “started firing at the airplanes.”

“America is leaving,” he said. “You can’t take everybody. Who will you take?”

Aderholt’s efforts saved the lives of roughly 2,000 Hmong. But many more were left behind.

“The running dogs of the Americans”

The rest fled the communists across the Mekong River into Thailand.

“We lost 30,000 during the war,” Xiong said. “We lost 50,000 after the war because the communists were coming after us.”

Those Hmong allies who didn’t make it to Thailand were sent to reeducation camps, what Xiong said are called “seminar camps.”

“Some never came back,” he said.

Xiong knows a woman who tried to cross the Mekong River with her family.

On the Thai side, authorities turned them away.

The communists captured them in Laos and executed her family after giving them 10 minutes to say goodbye to each other, Xiong said.

The girl survived and “stayed with her dead mother’s body for three days,” Xiong said. “Another group came and saw her and brought her across the river.”

She now calls Minnesota home.

“We have another girl who was 14 at the time,” he continued.

She paid a boatman money to cross, but the boatman tipped the boat in the middle of the river to drown everyone, Xiong said.

“She survived because she got stuck on a rock with her brother on her back,” he said.

The girl let go of her brother so she could swim across to safety.

Xiong’s pastor lost his wife after another boatman tipped their boat.

“He tried three times to save his wife and he couldn’t,” Xiong said. “So he swam across and he made it out.”

“There’s a lot of stories like this.”

“So just imagine the United States leaving Afghanistan,” he continued. “That’s what we’re doing.”

After U.S. passage of The Indochina Migration and Refugee Act in 1975, a path was paved for Xiong’s family to relocate to America.

The family spent time at several refugee camps in Thailand before making their way to the states.

During the interview process before heading to the states, authorities grilled Capt. Xiong and others about their commanding officers and where they fought.

The captain, a heavy artilleryman, was also quizzed on whether he fired 105-millimeter, 150-millimeter or 155-millimeter rounds.

“If you say 155, unless you are embedded with the Thai, only the Vietnamese fired 155-millimeter,” Xiong said. “So they would ask trick questions to see whether you are a true military person.”

In 1979, after a few years in Morgantown, Indiana, where Capt. Xiong — who once fired his artillery so hard his ear bled — worked as an elementary school janitor, the family settled in the Twin Cities.

Today, the Hmong community is an integral part of the state.

But Capt. Xiong cannot get back into Laos. His son has returned and faced extensive questioning from the authorities.

And to this day, Hmong rebels still hide out in the Laotian jungles.

Earlier this year, Radio Free Asia reported a renewed offensive by the communist government against those holdouts.

“They were classified as the running dogs of the Americans,” Xiong said.

Correction: an earlier version of this article misstated the alternate name for Long Tieng. It was also known as Lima Site 20A. An earlier version of this article also misidentified a man in a photo. He is Phi Noi Xuwicha.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.