JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-RANDOLPH, Texas — Brig. Gen. Jeannie Leavitt hasn’t been in charge of Air Force Recruiting Service for long, but there’s one thing she is certain of: The Air Force can’t keep recruiting the way it’s been doing it.

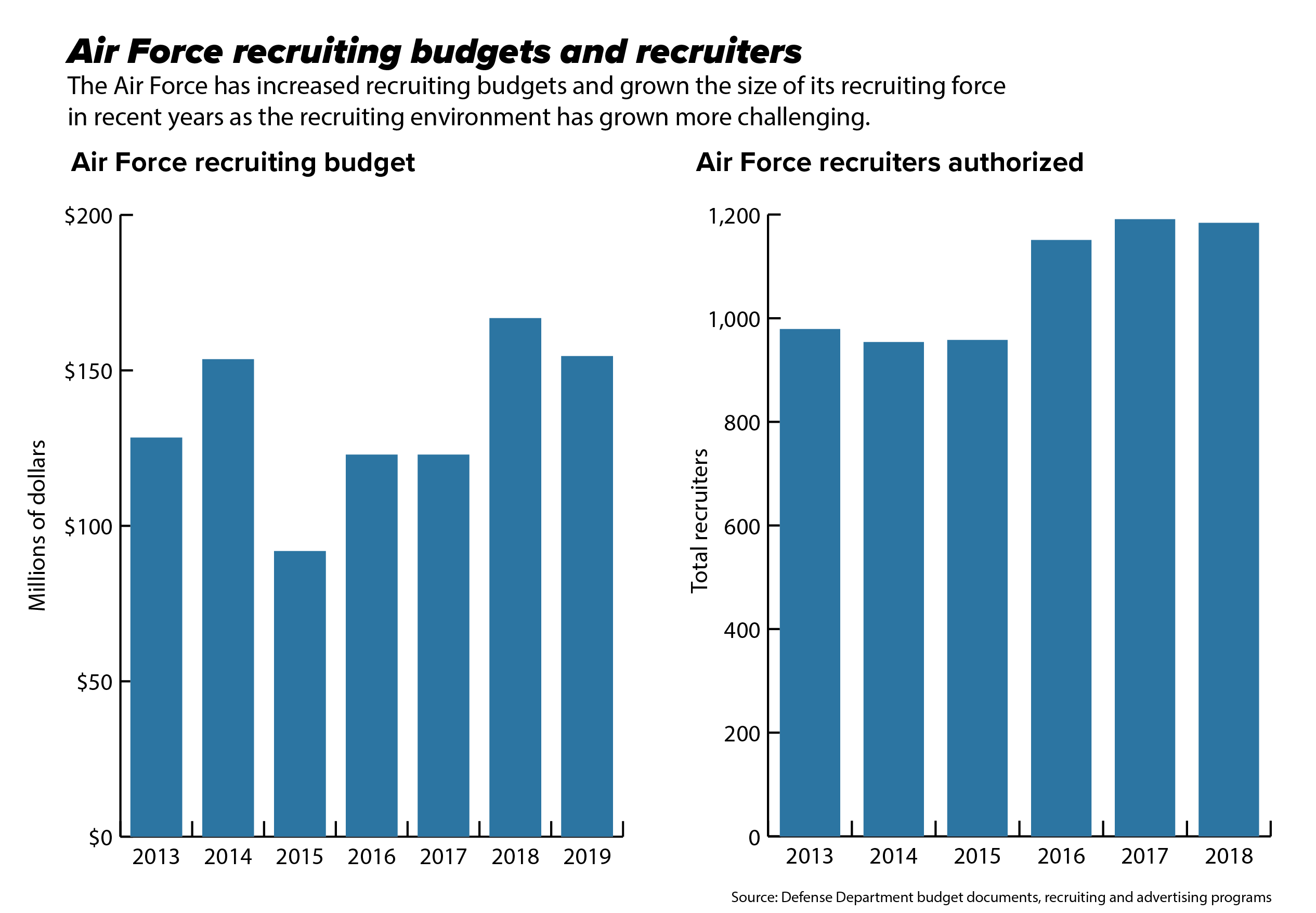

Too many recruiters are hamstrung by too many outdated procedures and “dead ends,” Leavitt said in a July interview at AFRS headquarters here in Texas. This has left the Air Force’s 1,184 recruiters — about 100 short of what they’re authorized to have — responsible for bringing in an average of 2.1 new recruits per month. That’s a far tougher expectation than recruiters from other services.

And while AFRS is planning to grow its ranks of recruiters by about 157 over the next five years and expand its offices to cover more ground across the country, the budget simply isn’t there to further swell the ranks.

So Leavitt, who assumed command June 15, wants AFRS to start figuring out faster, better and more technologically advanced ways to identify leads on potential recruits, convincing them to join up, and swiftly moving them through the process of becoming airmen.

“We have to take a fresh look at it and see if there’s more innovative ways to do things to optimize our recruiters’ time, as opposed to just adding more money and more funding to try to solve the problem,” Leavitt said. “While we’re happy that we’re increasing our numbers of recruiters to take some of the pressure off, we’ve also got to look at the innovation to help recruiters, not just more money.”

To do that, AFRS stood up an “innovation cell” in mid-July to dissect how the Air Force recruits, how it can do it better, and how it can find new ways to engage with the next generation of potential airmen. The team — which is working with the Austin, Texas, office of the Air Force innovation hub known as AFWERX, and has consulted with Air Education and Training Command — is still in the very early stages. But later this year, Leavitt said, she hopes it will have some suggestions on ways to improve.

But AFRS is already eyeing certain outdated aspects of the recruitment process for technological upgrades. For example, when the security clearance process begins for a potential new recruit, it’s currently the recruiter’s job to enter that recruit’s data in. AFRS wants to shift that responsibility to the recruit, who would plug in that information into a mobile app or online portal.

That way, the recruiter would have more time to carry out his primary mission of visiting schools, talking to potential recruits about the benefits of a career in the Air Force, or other necessary recruiting activities.

“One of our recruiters does not need to be the person inputting data,” Leavitt said. “A potential recruit could very easily do that. We take some of these administrative tasks, or tasks not directly related to recruiting, off the recruiter so they can concentrate on their primary mission.”

Leavitt also said AFRS is working on a lead refinement center, to help recruiters concentrate their time on the potential recruits who are most likely to qualify to serve, and follow through with enlisting in the Air Force. The refinement center could rate potential recruits from one to five stars, based on the candidates’ responses to questions, she said, and recruiters would concentrate on the four- and five-star candidates. That way, the recruiters don’t waste time they don’t have on someone who wouldn’t meet the physical standards or has something disqualifying in their background.

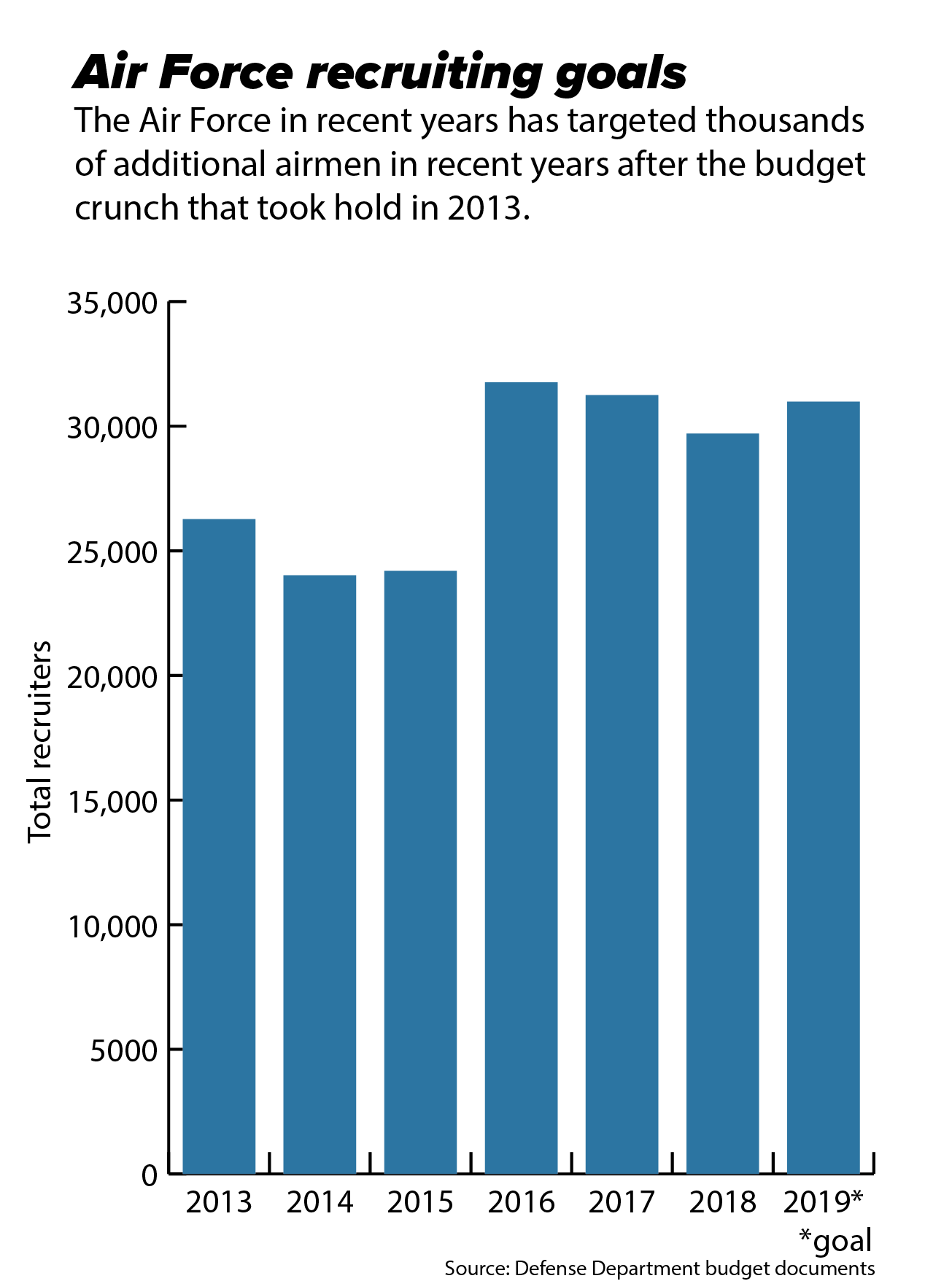

The Air Force has met, or come very close to, its recruiting goals for at least the last five years, and in 2016, brought in 31,507 airmen — the most since the Vietnam War. The Air Force recruited 29,831 new enlisted airmen in fiscal 2018, slightly beating its goal of 29,700. Leavitt said the Air Force is happy with the quality of recruits entering the service.

AFRS can do more to use technology to match new recruits up with jobs that best suit their talents, Leavitt said. If airmen are better matched with their ideal jobs based on their level of education, aptitude, and interest level, she said, they’ll be happier and more productive.

This could be as simple as steering a teen who enjoys working on his car toward a maintenance career field, she said. But in many cases, people don’t always know what they’re good at or interested in. So AFRS might create programs or apps designed to learn a particular recruit’s natural skills or interests, even if they’re hidden.

AFRS is just starting to look at ways to do this, she said, and is consulting with Air Education and Training Command and AFWERX. But she hopes “to move as quick as we can” to get it in place.

But the recruiting environment is getting more diffcult across the country. According to internal Defense Department surveys of young people people ages 16 to 21, interest in joining the Air Force has fluctuated a lot in recent years. In the months after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the number of young people who expressed serious interest in joining the Air Force jumped from 7 percent to 11 percent. That fell back down to 7 percent a few years later as the war in Iraq became unpopular. After the economic recession of 2008, interest rose again to 10 percent.

But the most recent surveys from last year show interest has again fallen again to 7 percent. With the economy and job market improving, the Air Force is facing more competition for talented young people.

To stay competitive, Leavitt said the Air Force has to focus on why airmen choose to serve the nation as it makes its pitch to potential recruits.

“We are doing something that has purpose,” Leavitt said. “When we go engage with folks, that sense of purpose and the why is going to be more of a draw than just the money. Being able to do something meaningful, with purpose, will resonate with a lot of people.”

And for some airmen, that means sharing their own, unique stories of service to help inspire young people to follow in their footsteps. Leavitt herself tells the story of how she made history in 1993 when she became the first female fighter pilot in Air Force history, as well as speaking about other airmen whose life improved as a result of joining.

It also humanizes the people wearing the uniforms, and makes it easier for potential recruits to see themselves doing the same.

“Everywhere I go, I run into these people with amazing stories, that really inspire you – wow, I want to be part of that,” Leavitt said. “It’s amazing how telling the stories really connects with the audience.”

The Air Force has had difficulty finding women to enter battlefield airmen jobs since all combat jobs were opened up to women in December 2015. The few female airmen who have attempted to join specialized career fields like Tactical Air Control Party have not yet been successful.

Leavitt said many people likely simply don’t know those jobs are now options for interested women after decades of being off-limits, and that the Air Force needs to keep pushing to educate the public.

“There’s a lot of people who don’t realize women can fly fighters,” Leavitt said. “It amazes me. [People say], we just thought that was something from Hollywood.”

Battlefield airmen needed

The Air Force is concerned about its overall ability to recruit enough new airmen into battlefield airmen jobs.

In June, the Air Force stood up the 330th Recruiting Squadron to focus on bringing in new airmen to serve in hard-to-fill special operations and combat support roles. It’s the latest attempt to fix the process of bringing on board new battlefield airmen since the service first realized it was broken 21 years ago, 330th commander Maj. Heath Kerns said in another July 23 interview.

“You can’t mass-produce them,” Kerns said. “There’s a very select few that have the right balance of skills and will and opportunity that will see them through an incredibly arduous two- to three-year pipeline of the toughest schools in the military.”

The 330th found that the most successful battlefield airmen recruits had one to two years of college – often with an affinity for history courses – and extensive athletic backgrounds in arduous, contact team sports like football and lacrosse, as well as cross country, swimming and wrestling.

So instead of trying to recruit people straight out of high school, the 91 recruiters of the 330th are trying targeting more mature young people in their first few years of college. Community college athletic programs are also fertile sources of recruitment, he said.

And since there are many opportunities for battlefield airmen recruits to drop out over their first two to three years, Kerns said, it’s important to recruit people who have already been through arduous physical training, like athletes, and are less likely to quit.

It’s a tough challenge. The 330th has 91 recruiters, Kerns said, tasked with bringing in almost 1,700 new battlefield airmen each year. That means each recruiter is responsible for finding 18 or 19 new airmen annually.

With the Air Force already short of enough battlefield airmen, it can’t afford to loan them out to serve as recruiters – aside from Kerns, a special tactics officer. So its recruiters partner with “developers” – retired special operators who act as coaches and mentors and help candidates learn mental resiliency and with their professional skills.

And recruiters at the 330th get out on the range, train and embed with special operators to know what they go through, Kerns said – and better tell potential recruits what to expect. That includes getting on the mic to call in close air support strikes, rucking, riding on a helicopter, and going through a one-week battlefield airmen preparatory course.

“You can’t have that depth of knowledge when you’re recruiting for all 160 jobs in the Air Force,” Kerns said. “We saw our people really have to focus in on this, to know what those cultures are, to start recognizing those things and be able to speak to [recruits] smartly. Not just because they had brochures that they read from, but because they lived it.”

It hasn’t been easy. Some colleges aren’t wild about recruiters trying to lure their best students away, Kerns said, or are suspicious of the military in general.

And there’s a branding problem, Kerns said, further complicating recruitment. Few members of the public even know the Air Force has special operators, let alone know what airmen like combat controllers do. Navy SEALs, on the other hand? Everybody knows them.

Leavitt is concerned that the post-9/11 security increases at bases – while understandable for force protection – had the unintended side effect of closing the military off from broader parts of society. And as a result, she said, many citizens don’t have as much interaction with people serving in the military, and don’t consider jobs such as battlefield airmen.

Leavitt also said said there are no further possible changes to serving requirements in the works since the last time they were changed a year and a half ago.

In January 2017, the Air Force dramatically loosened its standards on tattoos, which previously barred anyone with more than 25 percent of an exposed body part inked. Under the old rules, one in every five potential Air Force recruits had tattoos that required a review or could have disqualified them. But the new policy meant that airmen could serve with full sleeve tattoos on their arms or large back pieces.

The Air Force also relaxed its policies on marijuana use, to no longer disqualify potential recruits based on how many times they had smoked pot in the past, and reviewed its medical accession standards at that time.

When asked if the time has come for a new slogan or brand for the Air Force, Leavitt said that’ll be up to the service’s branding experts. But she thinks “Aim high” continues to resonate, and works on both literal and figurative levels, as far as setting lofty goals and meeting them.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.