U.S. counter-terrorism missions will soon place more emphasis on a little-known Pentagon program designed to help “surrogate forces,” rather than traditional allied units that are dependent on U.S. training, advice and assistance.

The shift comes as the Defense Department implements the 2018 National Defense Strategy, which prioritizes near-peer adversaries like China and Russia ahead of violent extremist organizations like the Islamic State.

“This evolving counter-terrorism [CT] operation construct will place even greater emphasis on successful programs, such as the 127 Echo program, which provides us viable surrogate forces designed to achieve U.S. CT objectives at relatively low cost in terms of resources and especially risk to our personnel,” Maj. Gen. James Hecker, vice director for operations from the joint staff, said during a congressional testimony Wednesday.

“The small-footprint approach inherent in 127 Echo ... in addition to lessening the need for large scale U.S. troop deployments, fosters an environment where local forces take ownership of the problem,” Hecker added.

The 127 Echo program is rarely discussed, but it involves shifting a greater share of the burden of waging war onto local partners, while allowing Americans to retain operational control over missions.

In a Politico exposé from July, one active-duty Army Green Beret officer described 127 Echo programs as “less, ‘We’re helping you,’ and more, ‘You’re doing our bidding.'”

The program is derived from U.S. Code Section 127e, which funds classified programs to use units from African governments as surrogate teams in direct action and reconnaissance missions, Politico reported. This is in contrast to other types of U.S. special operations missions, in which Americans assist African forces to accomplish their own objectives, and not those of the U.S.

Under U.S. Code Section 127e, the legal authority that is itself not classified, the secretary of defense and his chiefs can spend up to $100 million during a fiscal year to support “foreign forces, irregular forces, groups, or individuals” combating terrorism.

The approach pairs well with the Pentagon’s desire to reduce troops in Africa over the next three years.

In order to fully realize the 2018 National Defense Strategy, the U.S. military needs to pull troops from places where they’re focused on fighting violent extremist groups and shift them to focus on great power competition in places like the South China Sea or Eastern Europe.

To address that in Africa, the Pentagon came up with an “Africa optimization model” to identify how many troops can be re-tasked and from which areas, Hecker told Congress.

“We’ve done that with Africa, and we’re going to do that throughout the rest of the world,” Hecker said. "And realize as we pull troops, we’re going to use partner forces, as well as the 127 Echo programs that we talked about, to try to maintain pressure on the enemy.”

Hecker said that the distribution of forces across the counter-terrorism fight will be reviewed “monthly basically” to make sure the proper amount of pressure is applied in the right places to keep “U.S. and Western interests safe.”

The effort will focus on violent extremist groups capable of plotting and carrying out attacks against Western targets, both in Europe and the U.S.

Al-Qaida, which carried out the terror attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, is one example of a group the Pentagon wants to target. But that terror group, as well as newer and sometimes more violent ISIS affiliates, are not geographically confined to any one country.

RELATED

Hecker would not directly say in an open hearing where 127 Echo programs and U.S. counter-terror operations would be focused.

“There’s a couple different places,” he said. “Right now, we sit in a decent spot because we have maintained the pressure on a lot of the folks, al-Qaida, [and] ISIS in particular. ... So those are the areas that we look at."

ISIS has attracted pledges of loyalty from pre-existing terror groups across the globe. Its affiliates in Africa, for instance, include al-Shabaab splinter groups in Somalia and Boko Haram entities in West Africa.

How much counter-terrorism pressure, to include the 127 Echo program, will be applied and in which African countries, is yet to be definitively seen.

As for the presence of violent extremist groups in the Middle East, questions also remain.

“We’ve been issued an order to deliberately withdraw [from Syria],” Owen West, assistant defense secretary for special operations and low-intensity conflict, said at the hearing.

West had been asked by Congress why the U.S. was drawing down in Syria even though ISIS has the capacity to regroup.

“I do believe that [if] we look at the outset of ISIS, we were doing remote advise-assist,” he said. “And we do not need to be co-located to keep the pressure on the enemy.”

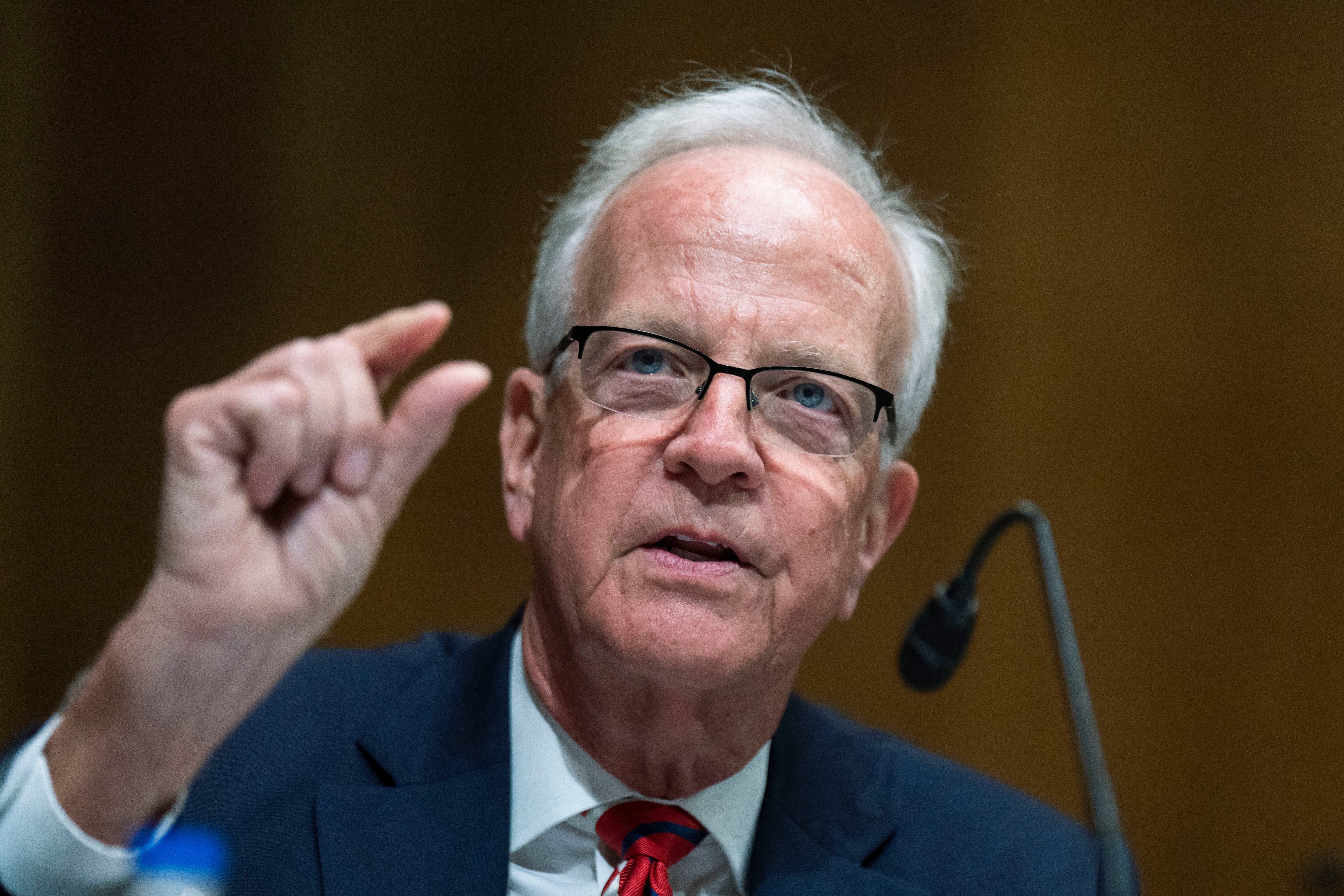

The 127 Echo program is the grandchild of similar initiatives from the mid-2000′s called Section 1206 and Section 1208, Washington state Rep. Rick Larsen noted during the hearing.

Back then, the funding was much more limited, at roughly $10 million. Now that the 127 Echo program has grown to $100 million, Larsen remained concerned that it hasn’t yielded more results in ending violent extremism.

“It seems to me that maybe we ought to be doing something different,” Larsen said, adding that the problem may come down to the local units used by these partner force programs. “Some of the countries that we work with maybe don’t have our history, our culture, our commitment to civil rights, human rights, and that causes a big problem for us when we are trying to create these partners."

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.