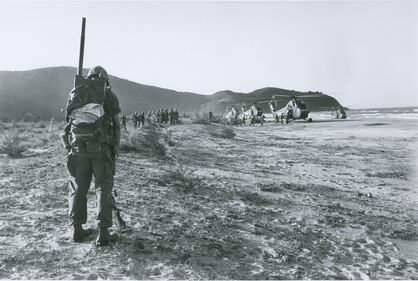

When mortar shell shrapnel exploded from a booby trap that hit Marines close to Chu Lai, Vietnam, a combat photographer was near the front.

A civilian buried with full military honors, Wisconsin native Georgette “Dickey” Chapelle was the first female war correspondent to die in combat.

Recently she was celebrated with the title of honorary Marine at the United States Marine Corps Combat Correspondents Association banquet in San Diego. In October 2016, Commandant Gen. Robert Neller approved the title for the award-winning war correspondent.

She was a five-foot-tall trailblazer who covered conflicts from World War II, to the Cold War, and finally, to Vietnam.

A writer and photographer, Chapelle’s photos had been featured on the covers and pages of Life, National Observer, Cosmopolitan, Reader’s Digest and National Geographic magazines.

One of her photos, which originally appeared in National Geographic in 1962, shows Vietnamese children responding to mortar fire. Another, which won the 1963 Photograph of the Year Award from the National Press Photographers Association, depicts Marine crew chief Nelson West and South Vietnamese soldiers on patrol near Vinh Quoi, Vietnam.

Iraq veteran and Coast Guard Reserve captain John Garofolo “heard about Dickey Chapelle completely by accident,” and was enticed by her story.

Chapelle was with Marines on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and met Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, “who allowed her to travel with a Forward Marine Medical Unit, until the Navy realized she wasn’t on the hospital ship she was assigned to and pulled her off the island and withdrew her military press accreditation,” Garofolo said.

Ten years later then-Commandant Shepherd “helped her regain her military press accreditation.”

In his book “Dickey Chapelle Under Fire,” Garofolo shares stunning photos — comprised after 24 years of digging and research — taken by Chapelle during her time as a combat photographer embedded with U.S. troops.

It follows the story of how she “abandons her studies at MIT, marries, and persuades the Navy — despite objections from every side, and at the time, meager credentials — to let her cover the front lines from the Pacific.”

“Chapelle overcame gender bias, a cheating husband, and ultimately earned the respect of the military and her media peers … in pearl earrings and cat-eye glasses, no less,” according to a media release.

The Wisconsin Historical Society houses some forty thousand photographs and written letters and works from Chapelle.

It includes a series of personal letters from then-Commandant Gen. Wallace Greene, whom she was quite close with — Greene had once given her an Eagle, Globe and Anchor pin from his uniform, Garofolo said. At times, Chapelle even talked Vietnam strategy with him.

“Imagine a reporter today writing the commandant of the Marine Corps and giving him advice on military tactics.”

The commandant sent Chapelle a letter after she was hospitalized for an injured knee after a parachute jump with Army Airborne troops:

“I’m delighted to hear this and to be reassured that you will soon be ‘fit for duty’ and in condition to try to outrun my Marines again.

Meanwhile, I want you to know that I and the many other Marines who claim you as a special friend are thinking of you and wishing you the speediest recovery.”

The night before her death, she had dinner with Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt, Marine Commander in Vietnam, Garofolo said, and “told him that when she dies, she wanted to be on patrol with the Marines.”

Image 0 of 11

She was near the front of a patrol as part of Operation Black Ferret with the 7th Marine Regiment when a Marine activated a tripwire. Shrapnel went through Chapelle’s neck and hit her carotid artery.

French Associated Press photographer Henri Huet was there to capture a hallowing image of a Navy chaplain delivering her last rites. Huet was later also killed in Vietnam.

Chapelle died on November 4, 1965. On that day, Gen. Greene sent a Marine-wide message, “She was one of us, and we will miss her.”

In her last few moments on Earth, Chapelle reportedly had murmured: “I knew this was bound to happen.”

After her death, Lt. Gen. Walt placed a plaque near the place of her death, Garofolo said. Her body was returned to the U.S. by a six-Marine honor guard.

Her photos live on — and finally she has her official title of ‘Marine’.

Andrea Scott is managing editor of Marine Corps Times. On Twitter: @_andreascott.

Andrea Scott is editor of Marine Corps Times.