Marine Corps aviation accidents have jumped 80 percent over the past five years, a Military Times investigation has found.

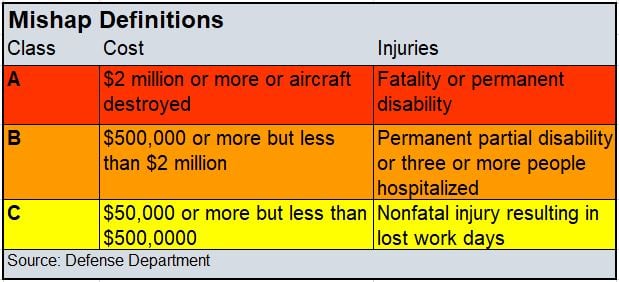

From fiscal years 2013 through 2017, the total number of Marine Corps aviation accidents rose from 56 to 101 per year. Most of the increase came from Class C mishaps ― accidents that cost between $50,000 to $500,000, or resulted in lost work days due to injury.

The Marine Corps is still looking for the “why,” said Marine Corps Col. Anthony Bianca, head of aviation plans and programs.

RELATED

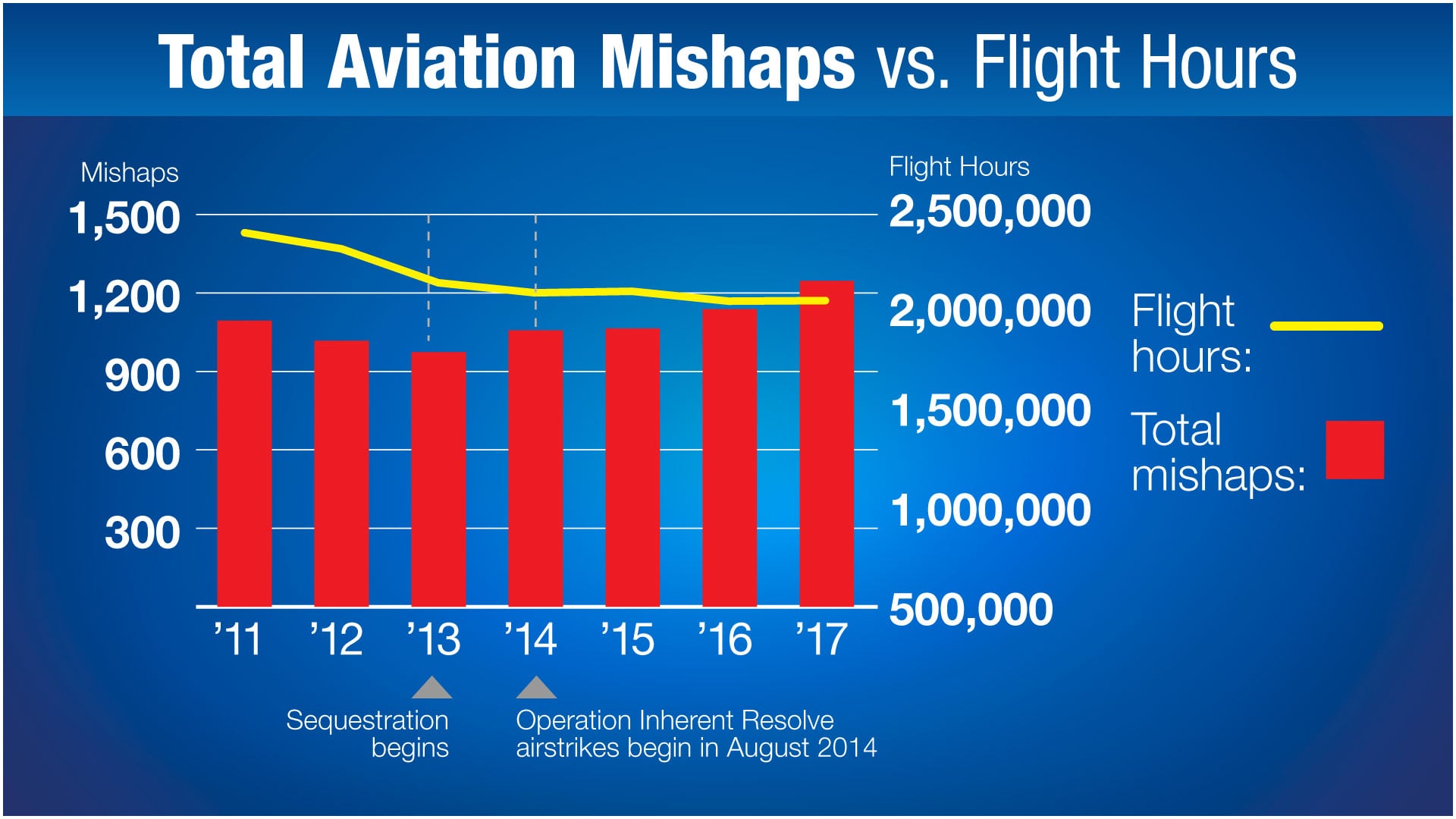

Like the other services, the Marine Corps’ latest spike in mishaps began in 2013, the same year that the automatic budget cuts known as sequestration took effect.

With a smaller budget, the Marine Corps cut overall flying hours; its manned attack helicopters, tiltrotors, fighter jets and cargo aircraft flew 60,000 hours less in fiscal 2017 than they did in fiscal 2013, according to service data. The Corps also cut skilled maintainers as part of mandated personnel cuts and lost experienced supervisors on its flight lines.

Less than a year later, the security landscape changed dramatically. In 2014 the U.S. began a three-year air campaign against the Islamic State. China began militarizing man made islands in the South China Sea. To respond, the Marines pushed the most ready aircraft forward. Marine Corps mishaps began to rise, jumping 20 percent between 2013 and 2014.

Impact of cuts

The Marines have not found a direct tie between accidents and funding, Bianca said. If a jet isn’t ready, it won’t fly, he said, so it wouldn’t have a mishap.

However, defense analysts point to other factors in play, particularly the loss of experience in both pilots and maintainers.

Marine Corps aviators are now averaging 14 to 16 flight hours a month, the service said, but Bianca acknowledged that number is generated by taking the average of all flight hours across the service.

“That’s an average, right? Our deployed guys are way past that,” Bianca said. “So when we say average flight hours, that’s a really watered-down number.”

Capt. Chris Harrison, a Marine Corps spokesman, said deployed squadrons generate roughly 50 percent more flight hours per month than the 14- to 16-flight-hour average, which bumps up the hours across the fleet.

One F-18 pilot who asked not to be identified described the 14- to 16-hour average as “total bullshit.” Instead, the non-deployed squadron had a 30-day average of 3.5 hours, and its 60- to 90-day average was worse, the aviator said.

“A deploying unit gets its flight hours and it gets its pilots and gets it airplanes,” Bianca said. Just-returned units, on the other hand, “are flight-time deprived.”

RELATED

Senior maintainers were cut, too.

“The cuts weren’t necessarily across the board and blind,” Bianca said. “We did try to set criteria, but it turns out we weren’t anchoring, at least from an aviation maintenance point of view,” all of the additional experience and qualifications not captured by a person’s occupational code.

An experienced flight engineer, with additional qualifications in tire maintenance, or oil analysis, “they’ve done a lot of maintenance, they start to know things,” Bianca said. The MOS didn’t capture which of those flight engineers were also qualified to inspect the work of more junior flight line maintainers.

“We never recorded that,” Bianca said. “We lost a lot of our good, solid lower-level leadership. And so we seek to train that back.”

Experienced depot contractors could not take up the slack, either, Bianca said.

“A lot of the engineers got out during the sequestration,” Bianca said. “Then we said, ‘We can hire you back.’ And they said, ‘Thank you very much ― no, you are not reliable enough for me, government.’ ”

RELATED

“So we couldn’t get the experience back,” Bianca said. “I think the Air Force will tell you the same thing. So that meant that airplane that sat in the depot, it should have sat for six months. It turns out, it’s in the depot for 18 months.”

By 2016 the Marines were reporting only 31 percent of their F/A-18 Hornets and 29 percent of their CH-53E fleet was able to fly.

The combined loss of skilled maintainers and pilot hours increases the chances a mishap will occur, defense analysts said. It also increases the chances that a potentially low-level incident could escalate to a Class A, when there’s a death, total destruction of the aircraft, or damage totaling $2 million or more. From 2013 to 2017, 49 service members were killed in Marine Corps aviation accidents.

“The compounding impact is there,” said John Venable, a senior defense fellow at The Heritage Foundation and former F-16 command pilot with more than 4,400 flight hours.

“This is where your mishap rate grows,” Venable said. “You got worse at everything if you flew two or less times a week. And the average units have been flying two or less times for five years. It lulls your ability to handle even mundane things.”

Mishaps rose as flight hours fell

Across the Marine Corps fleet;

♦ CH-53E Super Stallions flew 7,000 hours less in fiscal 2017 than in fiscal 2013, but mishaps rose from 10 to 17 in that time frame.

♦ F/A-18 A through D Hornets flew 5,500 hours less in 2017 than 2013. Hornet mishaps spiked in 2015 and 2016; then dropped in 2017. However, the overall numbers were still slightly higher than when sequestration began ― eight incidents in 2013 compared with 10 in 2017.

♦ C-130s flew 6,000 hours less in 2013 compared with 2017. Mishaps rose slightly during that time frame, from three per year to five.

RELATED

Almost half of the lost hours came from two aircraft the service is phasing out: the AH-1W Super Cobra and the AV-8B Harrier.

♦ Super Cobras flew 17,000 fewer hours in 2017 than they did in 2013, but incidence rates rose from two to four a year in that time frame

♦ Harriers flew 7,500 hours less in 2017 than 2013. Mishaps spiked to 10 accidents each in 2014 and 2016, but overall the mishap rate has held steady, from five incidents in 2013 to four in 2017.

On the other hand, the flight hours of MV-22s rose over the past five years as more aircraft came online.

♦ Ospreys flew 7,200 hours more in 2017 than they did in 2013 ― however, mishaps rose, too. from 10 incidents in 2013 to 17 in 2017.

Class C Mishaps

From October 2013 to September 2017, Class C mishaps ― accidents costing $50,000 to $500,000, or resulting in lost work days due to injury ― rose from 40 to 69 a year, accounting for the largest portion of the overall increase. Most of those Class Cs involved CH-53E Super Stallions, F/A-18 Hornets, MV-22 Ospreys, RQ-21A Blackjack drones and UH-1Y Venom helicopters.

Bianca said some of the rise can be attributed to the fact that the Marines’ airframes have become more expensive and complex, so a relatively minor incident can quickly meet the $50,000 threshold. The Marines’ smaller fleet of aircraft also means that it does not take many incidents to register a large percentage increase in accidents.

The narratives in the mishap data, one-liners that describe the incidents, did not reveal one primary cause of the additional Class Cs. Aircraft were struck by lightning during carrier operations; towing and flight deck collisions occurred during taxi maneuvers, maintainers sustained injuries by falling or or getting struck by airframe components.

Bianca said what the Marine Corps noticed was a rise in “unforced errors,” like a towing collision that occurred at home station, where there was not the added pressure of airstrike launches.

“A lot of the Class Charlies weren’t dangerous,” Bianca said. “What we found in our independent readiness review [on] the air ground mishaps was nobody had a heightened sense of what‘s going on.”

The rising mishaps have the Marine Corps’ attention now, Bianca said, and the service is trying to improve maintainer awareness and working on other initiatives to address the issue. The Corps also will begin spending the extra money in its budget, of course, but due to the time it takes to build replacement aircraft, it may take a while for that to have an impact.

He cautioned against assuming the increased accident rate is tied directly to funding, but noted that the Marine Corps is looking at how to better mitigate the impact if forced budget cuts return.

“What we can’t do is accept that effect” of rising mishaps, Bianca said. “Anyone taking a long view [on the budget] will say that [cuts] will probably happen again in the future.”

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.