The annals of U.S. military valor feature scores of heroes who concealed part of their medical history to serve their country.

Consider President John F. Kennedy. As a young man, he suffered a host of painful, disqualifying physical ailments, such as back pain and ulcers, but leaned on his father’s connections to get around the required Navy medical exams.

Lt. Kennedy went on to command a patrol torpedo boat that a Japanese warship sheared in half during World War II, and he later received a Purple Heart and Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

In recent decades, the lies told to enlist haven’t approached those extremes.

Nonetheless, fudging medical histories has been a key step on many troops’ path from applicant to recruit, according to a group of active-duty military recruiters who spoke with Military Times for this story.

“What it takes to get in the Army is, quite frankly, a lot of fraud and perjury,” one recruiter said.

But this tacit tradition — technically a crime — largely stopped in 2022, the same year the military’s recruiting numbers fell precipitously and today’s recruiting crisis came to the fore.

That year, the Defense Department brought a new medical records platform, known as Military Health System Genesis, online at Military Entrance Processing Stations, where applicants are medically examined before they can sign up.

Now, a year after Genesis was first used by MEPS, some military leaders acknowledge the new system has hindered recruiting.

RELATED

Multiple recruiters on the ground, from different services and locations, are more blunt in their assessments. They say Genesis has ended an applicant’s ability to gloss over or knowingly ignore minor medical issues, such as past use of ADHD meds or inhalers, before signing up.

In the process, those recruiters say, it has turned the military’s stream of applicants into a trickle and made a recruiter’s already-difficult job even harder.

“Nobody says it out loud in the wrong company, but the whole DoD knows that before Genesis we were able to put people through with a lot of different things, within reason, because whatever that applicant decides to disclose is whatever that applicant decides to disclose,” Joe Brown, a Marine Corps recruiter and staff noncommissioned officer in the South, told Military Times. “Now that Genesis exists, we can no longer hide things.”

Five recruiters who spoke with Military Times were given pseudonyms in this report and granted anonymity for fear of reprisal.

Broad concern

The recruiting crisis has evoked concern among leadership and on Capitol Hill. The Army missed its fiscal 2022 goal by 15,000 soldiers, and the other branches, except for the smaller Space Force, barely made quota or had to pull extensively from their pools of delayed-entry applicants.

Officials told lawmakers this month that they expect the shortfalls to worsen this fiscal year.

RELATED

Political leaders and partisan pundits blame today’s recruiting crisis on everything from so-called “woke” diversity training to kids these days being too fat and lazy to cut it.

Military brass have blamed an under-educated public, a roaring civilian jobs market and bad perceptions of service fueled by negative headlines.

But multiple recruiters who spoke with Military Times blame Genesis above all else.

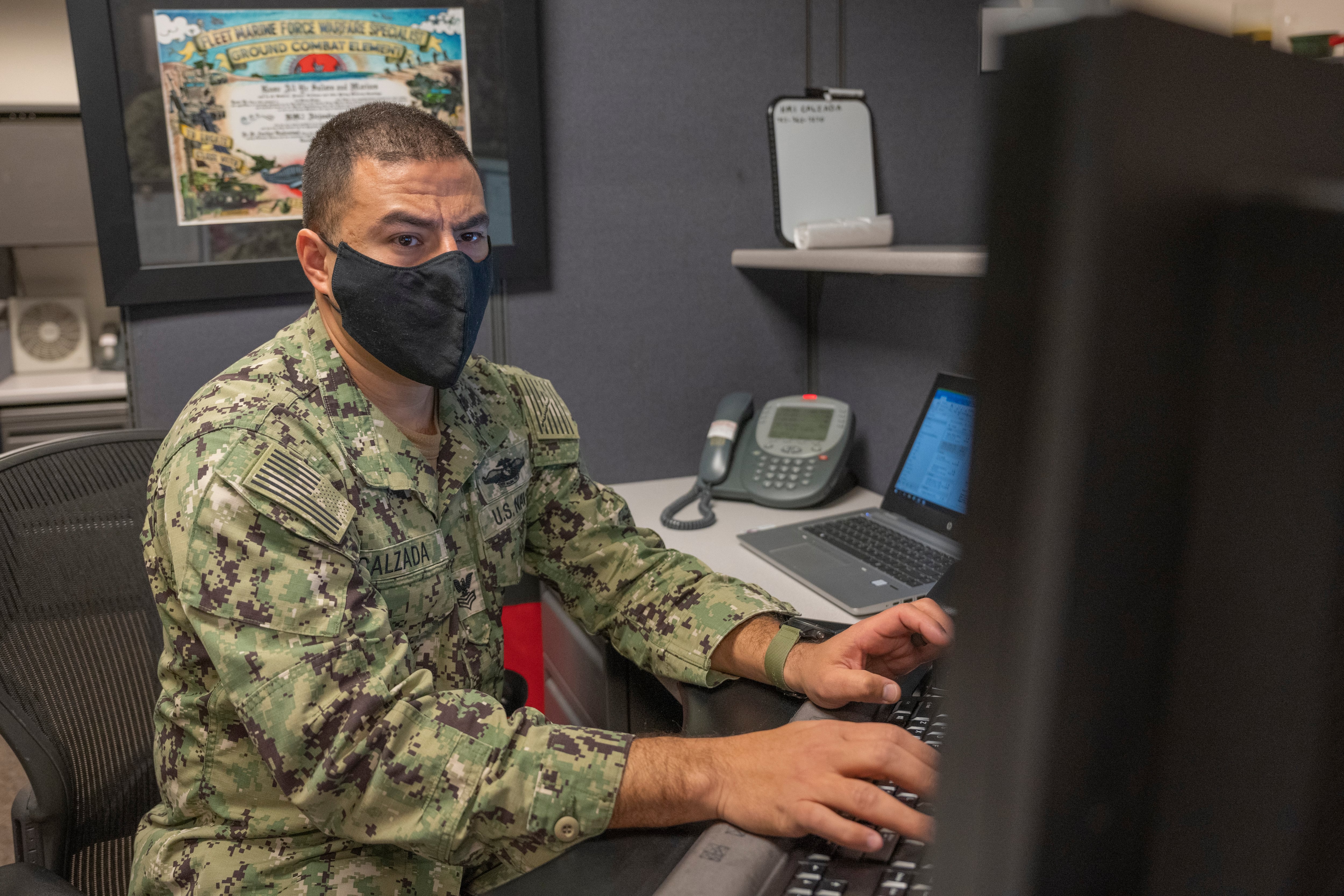

“When Genesis hit the scene, it was a night-and-day difference,” Navy recruiter Peter Harris, a petty officer, noted.

Once an applicant signs their consent, Genesis vacuums up the entirety of their medical history, flagging past and present health issues.

That makes it harder, some recruiters say, to squeeze applicants through despite past maladies they did not disclose — such as ADHD, depression or a years-old broken bone. Recruiting numbers suffer as a result. Previously, such applicants could enlist if they concealed, or genuinely had forgotten about, these issues.

Genesis is, broadly, a medical records system for service members, families and veterans that aims to make it easier for doctors to share medical information. It came about as part of a congressional mandate that the Defense and Veterans Affairs departments digitize health records. The contract for Genesis, awarded to Leidos, is worth $5.5 billion, according to the Government Accountability Office.

In the context of recruiting, the system allows processing stations to look at applicants’ civilian medical records, including hospital visits and prescriptions.

Genesis came to the military’s 67 MEPS locations in March 2022, when the head of U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command heralded it as “a leap in medical modernization.”

“The new electronic health record will follow applicants from the moment they walk through ‘Freedom’s Front Door’ into active duty, and eventually into the VA system,” Col. Megan Stallings, the command’s leader, said in a release at the time.

While multiple recruiters told Military Times that the system is flagging more applicants, Pentagon spokeswoman Lisa Lawrence said in an email that Genesis “does not reduce the population of qualified applicants.”

“Prior to screening at (MEPS), an individual has, or does not have, disqualifying medical conditions,” she said. Genesis “merely confirms the physical and mental readiness of applicants by enabling authoritative review of their health history.”

Lawrence said Genesis “is not the root cause behind the Services failing to meet their recruiting mission,” but she did not respond by Military Times’ deadline to emailed follow-up questions directly asking if the Pentagon believes Genesis was playing a role in the recruiting crisis.

Lawrence blamed, in part, low willingness of young people to serve, as well as “the residual effects” of the COVID pandemic that prevented recruiters “from meeting with youth and their influencers in our high schools.”

But data provided by the Pentagon shows each service exceeded its recruiting goals in fiscal 2020 and 2021, when pandemic-related lockdowns and disruptions to everyday life were far more prevalent.

In a nod to the current recruiting reality, the Pentagon in November began a pilot program that updated regulations for 38 medical conditions that would allow some recruits to join as long as they met certain timelines for previous treatment and diagnosis. The pilot will be in effect through June, Lawrence said, and then the DoD will analyze whether it would make sense to extend the program.

To ease the ongoing recruiting crisis, senators have urged the DoD to allow applicants who had sought treatment for some mental health issues.

“We disqualify young men and women if they’ve seen a psychiatrist or if they’ve been on medicine for mental health, and yet we want them to try to improve themselves,” Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, said during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing in March.

“There are still people who are eager to join — it’s just really, really hard to actually get them in,” said Harris, the Navy recruiter. “Because, you know, they can see their medical history. I think that would be the biggest issue as to why recruiting numbers are so terrible.”

New hurdles

Smith, a soldier who has spent the last few years recruiting, admitted he helped applicants massage their medical history to get them in before Genesis — up to a point. He wouldn’t, for example, allow someone with asthma to get through.

But of the 30 applicants he recruited, he said, “only one was clean as a whistle.” In some cases, the problem wasn’t medical; a history of marijuana use was also something he would “grease wheels for.”

The recruiter also lied about his own medical history to enlist.

As Smith went through the applicant pipeline, officials requested medical paperwork for a procedure he underwent years ago, but he had no way to get those records.

“My recruiter, for me to get in, just made up medical paperwork, made up a doctor and submitted it,” Smith said. “And that’s how I joined. That’s what it takes, or else I would never be in.”

He’s not the first Army recruiter to speak out about Genesis’ impact on the mission. Three other Army recruiters voiced similar concerns to Task and Purpose in September.

Some young people whom Genesis flags acquire waivers and go on to enlist.

At least one in six military recruits received waivers to enter service in fiscal year 2022, the highest proportion in at least 10 years, according to service data.

But some, dispirited by delays caused by Genesis, back out entirely, while others end up unable to join, recruiters say.

Meanwhile, recruiters say they still face the pre-Genesis pressures to make their quotas, despite the new hurdles.

“I’ll walk around Walmart at 11 o’clock at night just begging someone to sit down in my chair so I can go home,” said Jon Johnson, a Marine recruiter. “I’ve got a wife and two kids. This sh-t’s not it.”

Yes means ‘your enlistment stops’

Recruiters have a tongue-in-cheek saying about how an applicant’s answers to yes-or-no questions on the military’s medical history questionnaire decides their fate.

The form requires yes or no answers. Hay fever? A change of menstrual pattern? Broken bones?

“Yes” stands for “your enlistment stops.” “No” stands for “numerous opportunities.”

“You never had asthma. You never had ADHD,” the Navy recruiter said. “You broke your leg when you were six? “Don’t talk about it.”

In the Air Force, Genesis’ arrival is disqualifying more applicants during the medical process, while making medical screenings longer, Maj. Gen. Edward Thomas, head of Air Force Recruiting Service, told Military Times in February.

Applicants don’t formally sign up until they’re cleared, and that longer process gives them more time to back out.

“Genesis is the right thing to do — it’s mandated by Congress,” Thomas said. “But it wasn’t ready for deployment in recruiting.”

“If MHS Genesis had not been implemented in recruiting at the same time that the recruiting market had a sharp downturn, it would have been far more manageable,” he added.

The Army did not directly answer questions about whether Genesis is driving recruitment challenges, but Army Recruiting Command spokesman Maj. Tom Piernicky acknowledged that sorting through the medical records Genesis flags “is time consuming and labor intensive, and has added an element of complexity to the accessions process for initial entry applicants.”

“The Army is committed to maintaining high enlistment standards, and MHS Genesis has helped the Army to better determine an applicant’s suitability for Service from a health and safety standpoint,” Piernicky said. “With regard to current challenges, the Army, along with the other services, continue to face unprecedented recruiting conditions due to a combination of factors.”

Navy Recruiting Command spokesman Cmdr. Dave Benham said the access to additional information that Genesis provides increases “average processing time,” but that the system allows the Navy to make more informed decisions regarding an applicant’s medical history.

“It also means fewer cases of Sailors entering the Navy that later go through medical review boards for pre-existing conditions that were not disclosed at accession,” he said. “Our recruiters are working hard to consider the entire person and to reduce barriers to enlistment where possible, while still ensuring we deliver on that mission.”

Marine Corps spokesman Jim Edwards blamed the same societal factors as the Pentagon and other services, as well as “media inflation,” for the struggle.

Genesis, Edwards said in an email, “has extended the contracting timeline for some applicants, but it is not the sole or main factor driving recruitment difficulties.”

“Our hard-working Marine recruiters continue to accomplish the assigned recruiting mission and we remain on track to accomplish the FY23 accession mission,” he said.

Delayed gratification

Recruiters said common holdups for applicants include ADHD medication, antidepressants and counseling. Mental health was also a common reason that applicants sought medical waivers in FY22, according to data provided by DoD.

Diagnoses of mental health conditions are higher for Gen-Z than for older generations. The American Psychological Association reported in 2019 that Gen-Z and millennials are more likely to report their mental health as fair or poor, and more report receiving treatment or therapy, compared to Gen-Xers or baby boomers.

RELATED

Recruiters were quick to add that Genesis creates hurdles even for applicants who do what’s legally required of them: honestly report what they remember of past medical conditions. Some applicants have forgotten about issues that left no long-term effects but require additional documentation once they pop up in Genesis.

Don Wilson, a Marine staff NCO recruiter, said he thinks a screening system like Genesis has benefits in ensuring that only applicants ready for the rigors of the military can join.

But he wishes applicants didn’t get flagged for having attended counseling after a difficult life event or being prescribed an EpiPen years ago.

Recruiters say the increased disqualification of applicants caused by Genesis makes it that much harder for them to hit their monthly quotas, exacerbating the long hours and grueling sales pitches that have long defined military recruiting.

Such applicants can still make it into the military if they provide additional medical documentation or secure waivers for certain conditions, but recruiters say that is often easier said than done.

Marine recruiter Johnson and others said Genesis increases the time between a potential enlistee walking into his office and shipping to boot camp, even if they are fully qualified.

And when dealing with impatient teenagers, time isn’t a resource recruiters can afford to waste.

Johnson recalled a 17-year-old girl who came into his office and who was clearly in outstanding shape and healthy enough to ship off to Marine basic training.

Yet health records pulled by Genesis showed that she had sprained her wrist as a child, an injury that hadn’t required surgery, stitches or painkillers, Johnson said.

He had to chase down documentation proving she was good to go, and it took two months to get her processed, Johnson said.

Recruiters for other services echoed the Marine’s take: that Genesis makes processing too long, allowing kids to back out or change their mind before they have signed their contract.

“I had to battle the disinterest” of the teen, Johnson said. “For most people, they’re looking for instant gratification. That’s also a common trend we’ve seen out here: If I can’t get them something now, they generally leave.”

“It comes to the point where they’re like, ‘This is too much work, I’m just gonna go apply at Starbucks,’” Navy recruiter Harris said.

Adapting and overcoming

Factors besides Genesis make it challenging to recruit.

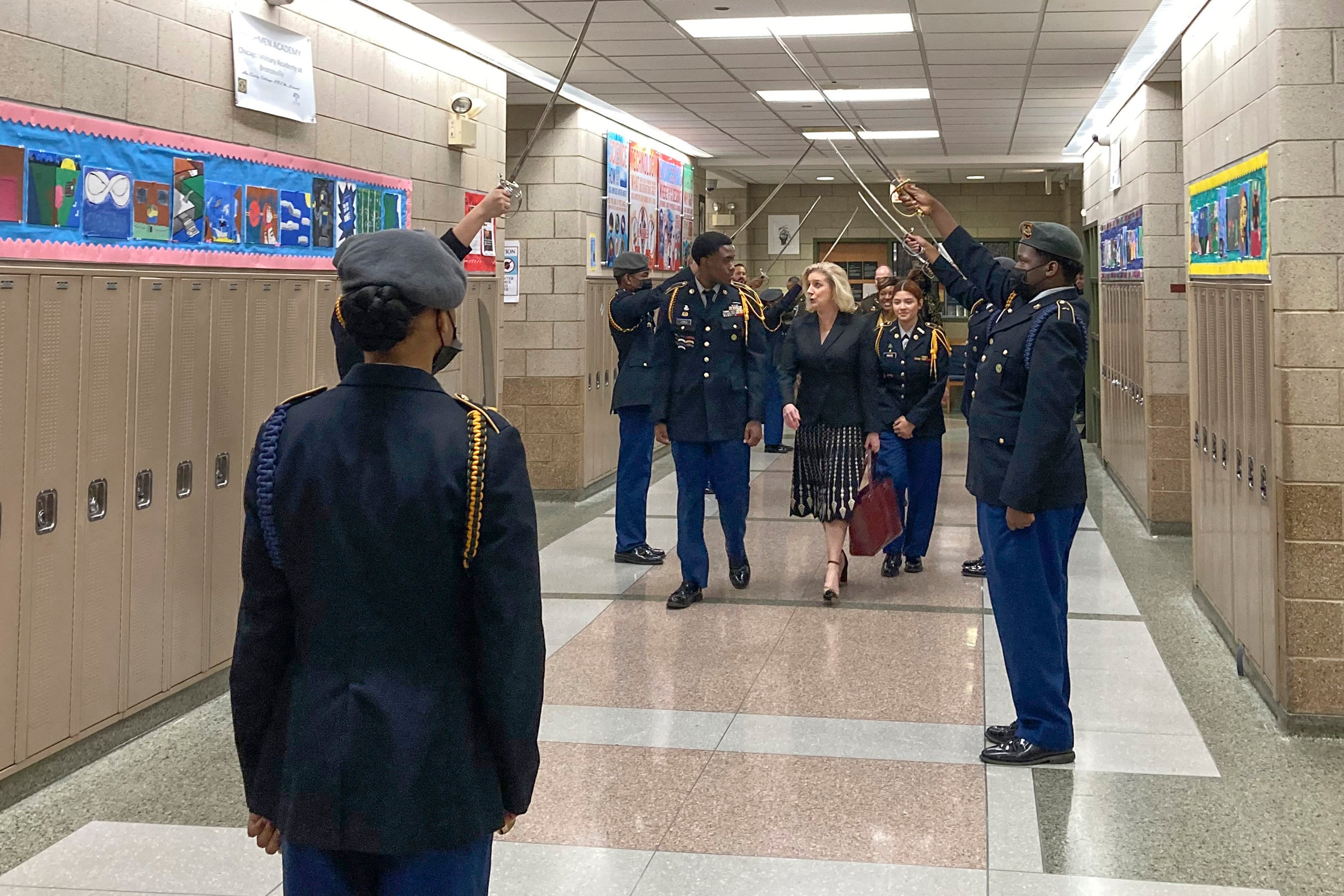

In addition to poor fitness and low desire to serve in the military among teenagers, recruiters said many schools do not welcome them onto their grounds, a challenge exacerbated by the pandemic. Some parents don’t want their babies to take on the military’s risks.

But these problems existed long before today’s recruiting crisis, the Marine recruiter Brown noted.

“Since the Marine Corps existed, there’s been obese people,” he said. “There [have] been low test scores. That’s something we’ve always dealt with.”

What’s new is Genesis.

Before 2022, Brown said, he had never missed a monthly target during his four years as a recruiter.

Then came Genesis. He started missing his goals, and it took him a few months to get back on track.

Meanwhile, the services are working to adjust to the longer recruiting timelines associated with Genesis.

The Army last year activated some of its Reserve doctors to deal with a backlog in waivers.

In addition, the Army and Air Force have instituted a Genesis “prescreen” so that applicants and recruiters can better understand what parts of a medical history will be relevant and require documentation at MEPS before they arrive at the processing station, according to service officials.

Navy and Marine Corps officials said that, as was the case before Genesis, recruiters review an applicant’s medical history with them to determine if they have any medical conditions that will need to be addressed at MEPS.

Still, several recruiters told Military Times that their leaders’ response to recent shortfalls has been to tell them to work harder. Make more calls. Improvise, adapt, overcome.

Brown said he used to work about nine hours a day as a recruiter. Now it’s up to 12, plus weekends. He said that’s less than most of his peers.

These days, Harris, who has been a Navy recruiter since before Genesis, said many recruiters he knows are on antidepressants — one of the very things for which Genesis screens applicants.

Military Times reporters Rachel Cohen, Davis Winkie and Meghann Myers contributed to this report.

Irene Loewenson is a staff reporter for Marine Corps Times. She joined Military Times as an editorial fellow in August 2022. She is a graduate of Williams College, where she was the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.