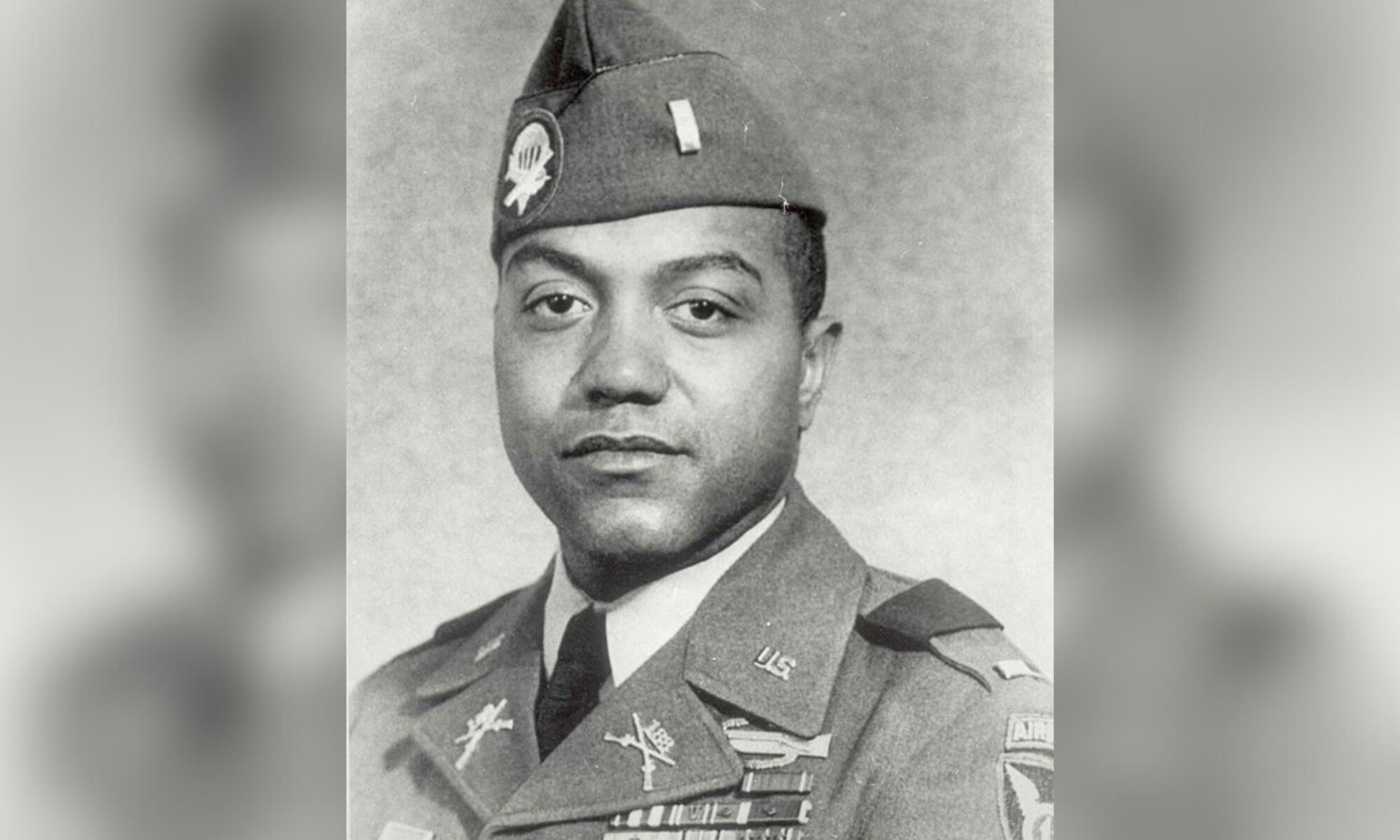

In 1997, after being denied the award for more than 50 years due to discrimination, 1st Lt. Vernon Baker finally received a Medal of Honor for his heroism during World War II, making him one of the seven Black American troops awarded the medal for their service in the war.

Baker was born in 1919 in Cheyenne, Wyoming. When he was 4 years old, his parents were killed in a car accident, leaving him and his two sisters to be raised by their grandparents in Clarinda, Iowa. His grandfather taught him how to shoot game to help feed the family and Baker considered him the most influential figure in his life.

Baker graduated from Clarinda High School. In 1939, after Baker’s grandfather died of cancer, Baker supported the family as a railroad porter, a job he detested.

RELATED

Seeking a more satisfactory profession, Baker tried enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1941, but the recruiter turned him away, saying, “We don’t have any quotas for you people.” Baker waited a few weeks and tried again with a different recruiter — and was accepted on June 26, 1941. He hoped to get into the Quartermaster Corps, but had to settle for the infantry.

“I didn’t say anything,” Baker later said, “because I was going to get in.”

Baker took basic training at Fort Wolters, Texas, which from the start subjected him to a level of Jim Crow prejudice he’d not experienced in the Midwest, but he quietly endured it in accordance with what his grandfather had told him: “If you want to live, boy, learn how to conform.”

Baker was then assigned to the 25th Infantry Regiment at Geiger Field near Spokane, Washington, and later at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. At that point, Baker had achieved his goal of becoming a supply sergeant, but in October 1942, he was offered an opening in Officer Candidate School.

Baker was hesitant — he liked his job as a supply sergeant, but an officer’s commission meant issuing orders and shouldering much more responsibility. Still, he decided to give it a try, and after 13 weeks of training at then-Fort Benning, Georgia, he emerged as a second lieutenant in charge of a weapons platoon in C Company, 370th Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated division that had not seen action since its bloody baptism of fire in the 1918 Meuse-Argonne campaign during World War I.

On June 15, 1944, Baker’s regiment departed Hampton Roads, Virginia, for Naples, Italy. They marched north to join the Fifth Army, which was slowly, steadily fighting its way through mountainous terrain and well-prepared German defenses along the Gothic Line.

Over the next several months, Baker developed a good working rapport with his troops. In October, the squad he was leading came under enemy fire, killing three men and wounding Baker.

After recovering in the 64th General Hospital at Pisa, Baker returned to his unit in December to discover himself the senior officer of his regiment until March 1945, when Capt. John Runyon and two other white officers arrived to take charge of C Company.

On April 5, the 1st Battalion of the 370th was assigned the task of taking Aghinolfi Castle, a hilltop stronghold near Viareggio with an artillery directing post that had already repulsed three assaults. At the fore were 15 members of C Company, led by Baker. More than 70% of the unit was filled with new, inexperienced replacements.

Two hours after setting out, they were 250 yards from the objective. Baker surveyed the area and — bringing his childhood hunting talents into play — shot two German soldiers in an observation post and two more he spotted near a camouflaged machine gun nest. Runyon had come up to confer with Baker when a grenade landed nearby — fortunately for them, it proved a dud.

Runyon then retired to a hill summit behind them while Baker resumed his crawling advance, picking off four German soldiers along the way. By now aware of C Company’s presence, the Germans loosed a mortar barrage, killing six troops. American artillery silenced them for a while, but German forces soon counterattacked.

Runyon told Baker he was going back to bring up reinforcements to cover C Company’s withdrawal, but Baker knew better — between the heavy enemy fire and the grenade incident, his nerves had cracked and he would not be coming back.

After holding out against more mortars and a weapons platoon whose crew was dressed as medics, Baker’s platoon was down to eight men, all low on ammunition, and he made a painful decision: “My men wanted to stay, but I wanted to ensure some of them stayed alive.”

Baker covered the retreat in two increments, but in the process, a soldier was wounded and their medic killed by an enemy sniper.

Crawling back, Baker used grenades to destroy two enemy machine gun positions before finally reaching the forward aid station. His 25-man platoon had fought for 12 hours and lost 19 dead or wounded. After accounting for his survivors and turning in every identification tag he’d been able to collect while fighting, Baker fell to the ground and vomited.

Baker and Runyon barely recovered from the past two days’ ordeal before they were temporarily assigned to 2nd Battalion, 473rd Infantry, to apply their experience toward another assault. They overran the objective without loss, no doubt because of the casualties Baker and his platoon had previously inflicted on them.

A few days later, Runyon recommended Baker for the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest American military decoration and the highest the Army gave to Black soldiers at the time. On July 4, 1945, Baker received the medal near Viareggio. Baker also received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

After the German surrender, Baker did occupation duty in Italy until February 1947, followed by six months’ leave.

During the Korean War in 1951, Baker was among the first Black officers to lead an all-white company in a newly integrated Army.

As the armed forces were reduced, however, Baker was decommissioned, resuming his duties as a master sergeant. During 13 years at then-Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he trained as a paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne Division and spent time in the 11th Airborne Division but did not get his lieutenant’s commission back.

Baker retired from the Army on Aug. 31, 1968, and spent the next 20 years working for the Red Cross.

In 1996, he learned that his wartime record was being reevaluated, and on Jan. 13, 1997, he was among seven Black Americans to have their WWII Distinguished Service Cross upgraded to the Medal of Honor. He was the only one of them still alive to receive the award from President Bill Clinton.

In 2008, Baker received the American Spirit Award from the National WWII Museum.

Spending his final years in Benewah Valley, Idaho, Baker married three times and had three children. After a long struggle with cancer, Baker died July 13, 2010, at 90 years old in St. Maries, Idaho. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.