Editor's note: This article was published on May 8 at 4:08 p.m. EDT and has been updated.

The third time the high-pitched alarm rang "deedle deedle" in the F/A-18F Super Hornet's cockpit, it was clear that something with the air flowing into their regulators had gone horribly wrong.

"Deedle-deedle" the cockpit rang, for the third time since they'd gotten in the two-seat F/A-18F Super Hornet. Maybe his flight officer had taken his mask off again, and the oxygen free-flow was setting off alarms.

"That's when I realize my lips were tingling, my fingers are tingling, and I'm like, 'S---hit, man, something's wrong,' " a Navy pilot recalled. "And the guy in the back's like, 'Hey, dude! My fingers are blue!' "

They had just taken off from The flight had just gotten started over Naval Air Station Fallon, Nev., when they recognized the blurred judgment and delayed reflexes caused by a lack of oxygen. suffering from a lack of oxyen that and Suddenly the pilot had to figure out how to land the $65 million jet on a cloudy day, in a rocky stretchpart of Nevada where mountains peak atround 6,000 feet.

"So the problem is, how low can you go? And you’re doing this hypoxic," recalled the 10-year, 1,000-hour West Coast-based Hornet pilot, who asked not to be named out of concern over his 10-year career. Rhino driver, who asked not to be named.

The pilot and naval flight officer were suffering from a lack of oxygen to the body's tissues, a condition known as hypoxia, which can causes tingling and numbness leading to confusion and eventually to unconsciousnessblack out. Some will lose the capacity to speak, others are disoriented to the point of acting drunk.

Physiological episodes — including hypoxia and decompression sickness from loss of cockpit air flow — Hypoxiawhich are ishard to diagnose after the fact, are is a confirmed cause in at least 15 naval aviation deaths in the past two decades — and aviators are worried more pilots may die before officials fix the problems.

Naval Air Systems Command is scrambling to implement fixes, but the brass has underplayed the severity and frequency of the danger since it emerged in a February congressional hearing, according to interviews with pilots and official reports.

These show a troubling rise in the number of breathing and pressurization problemshypoxia cases, and that Navy and Marine F/A-18 Hornet and EA-18G Growler aviators view the problematic On-Board Oxygen Generation System as the fleet's most pressing safety issue 10 times over. Despite these issues, aviation bosses have not grounded the fleet, a common response to aircraft safety issues. most visibly, but also a disorientation to the point of acting drunk. Some victims will stop talking for several minutes but have no idea that they're not asking for help.

"There’s only one thing that scares the s---hit out of guys that fly the airplane, and it’s OBOGS," the pilot said in an interview.

Another danger facing aircrew is decompression sickness from a loss of cabin pressure, which has many of the same symptoms as hypoxia, with the added sign of joint pain. And if it's severe enough, it can cause permanent disability or death.

In the past 20 years, physiological episodes have caused 17 Class A Mishaps— an accident that results in aircraft damage of more than $1 million and/or a death or permanent disability — according to the Naval Safety Center.

Of those, 15 resulted in a death. And those are only the ones where hypoxia or DCS were confirmed causes, because the safety center doesn't keep track of mishaps where they could have been a causal factor.

That day in Nevada, the pilot and the NFO pulled out their back-up oxygen bottles, landed the plane and met with the squadron's safety officer to file a report. It turned out, the pilot said, that the jet's OBOGSn Board Oxygen Generation System had stopped producing oxygen. What's more, he added, the filtering material inside the system had just been cleaned and it was the jet's first flight with a fresh oxygen generator.

That was back in 2007, when aviators reported annually a the Navy was fielding a dozen or so reports of physiological episodes — the technical term for the effects when a plane stops producing oxygen, pumps a toxin into the cockpit or loses pressurization — a year.

The rates were troublingtoo high for comfort. so In 2010, Navy aviation made a pushed to get pilots and aircrew to report every time they even thought they'd had an episode. And over at NAVAIRaval Air Systems Command engineers focused on how to improve OBOGS and the environmental control system — the pieces of the airplane that keep clean, dry air circulating.

Navy officials say it's progress that more fliers are recognizing and reporting physiological episodes. They say the causes of these distressing incidents are varied across the air systems' dozens of components, many of which have been modified and are now being more regularly checked. Meanwhile, engineers work to develop sensors that detect air contamination and low oxygen levels.

The Navy's air warfare director summed up the dilemma in a tense exchange during a February hearing with an apt comparison.

"It’s like chasing a ghost," said Rear Adm. Mike "Nasty" Manazir, a career Navy pilot. "You can’t figure it out, because the monitoring devices that do this are not on the airplane." he said.

But The fixes, pilots say, aren't coming quickly enough.

"It seems like all we do is react to hypoxia incidents and troubleshoot each jet, but we aren't actually doing anything to prevent it from happening," said an East-Coast F/A-18 pilot and hypoxia victim, who also asked for anonymity.

In interviews, NAVAIR engineers and leaders detailed their efforts to fix the systems causing hypoxia and decompression sickness; spokespeople for Marine Corps aviation and the Navy declined to comment for this article.

Have you worked with ECS and OBOGS or experienced breathing and decompression issues while flying? Share your experience or perspective to Navylet@navytimes.com.

The Air Force's F-22 Raptor has suffered from similar problems. After hypoxia concerns arose in 2011, the brass grounded the F-22 fleet for four months. After they resumed flying, two F-22 fliers went on "60 Minutes" to say they wouldn't fly the aircraft until the problems were fixed. In July 2012, the Air Force said it had

they

fixed the faulty valve on the pilot's life support vest that was causing the oxygen deprivation.

The Air Force also added an automatic back

-

up oxygen system, while the Navy has stuck to its manual procedure.

In a safety survey of Hornet and EA-18G Growler squadrons early this year, OBOGS was ranked number one of 100 listed problems, with 19 out of 26 reporting squadrons rating their concerns a 10 out of 10.

Other top concerns included a lack of an oxygen monitor in the aircrew mask, cabin pressure surging and lack of cabin pressure testing equipment — all issues that can result in physiological episodes.

INCLUDE SOMETHING HERE ABOUT HOW THIS RANKS RELATIVE TO OTHER SAFETY ISSUES, ACCORDING TO PILOTS safety sheets

The air flow issues have bedeviled the Navy and Marine Corps' fleet of F/A-18 Hornets, EA-18G Growlers and T-45C Goshawk trainers, all of which use the OBOGS. In the case of air contamination, there are no warning systems to alert the aviators breathing disorienting and potentially deadly gases. Complicating the assessment of the breadth of the incidents is the general

abiding

reluctance of pilots to report what seem to be physiological problems, which can remove their flight status.

Meanwhile, the reported number of events

hypoxic episodes

is skyrocketing.

There, there were

Aviators reported 15

reported

physiological episodes in 2009, concentrated in strike aircraft and the trainer jets that aviators learn on, according to Naval Safety Center data.

provided to Navy Times

By 2015, the fleet reported an eight-fold increase to 115 episodes: 31 in the T-45C Goshawk trainer and 41 in Hornet variants, plus

another

19 in the EA-18G Growler. The Marines also reported a spike that year, including hypoxia and OBOGS failure in the brand new F-35B joint strike fighters and seven more events involving its legacy Hornets, as the F/A-18 A through D variants are known.

The numbers steadily grew, and reports started coming in from P3-C Orion patrol aircraft and the MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor transport vehicle, but stayed highest in the fighter communities and the jets they learn on in flight school.

The safety center keeps close track of physiological episodes, which include everything from loss of oxygen or air contamination to black-outs from G-Forces, and it one case, an MH-60 Seahawk aircrewman who severed his finger during a hoist.

For the purposes of this story, Navy Times zeroed in on those of the more than 750 Navy and Marine Corps reports provided to include only the instances of hypoxia, decompression sickness, loss of pressure and warnings or failures of OBOGS and ECS.

By 2012, there were 93 reports in 11 airframes — 55 of those in Hornets and Super Hornets, and another 26 from the Hornet trainer T-45C Goshawk. Of those events nine were Marine Corps F/A-18s.

The numbers shot up again in 2015, with 115 episodes, which included 31 in the T-45 and 41 in Hornet variants, plus another 19 in the EA-18G Growler. The Marines also saw a spike that year, including hypoxia and OBOGS failure in the brand new F-35B joint strike fighters and seven more events involving its legacy Hornets.

Officials say that the rise in reports comes from greater awareness, but it's unclear whether

numerous

updates are making a dent. The first two months of 2016 saw 26 episodes, putting the numbers on track to pass 100 again.

"We are seeing a decrease in the severity of these types of episodes. That’s over the past few years," said Rear Adm. Dean Peters, head of the Naval Air Warfare center Aircraft Division. "This is a little bit subjective, because it’s based on the narratives from the aircrew. But there’s so much awareness out there, there’s so much training."

In early March, NAVAIR invited Navy Times out to its Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, headquarters to sit down with the lead systems engineers, the tactical aircraft program manager and the Marine Corps major who heads the physiological episodes response team there, and to see the troubleshooting labs for these systems.

Gasping for air

Experts warn that some breathing issues appear to stem from exhaust entering the breathing system while planes line up for take-off. Here, an F/A-18C Hornet with Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 312 catapults off the carrier Harry S. Truman.

Photo Credit: MC3 Karl Anderson/Navy

Physiological episodes can be caused by everything from equipment failure to human and maintenance errors, but the Navy has shored up efforts to get depressurization and OBOGS failure under control by overhauling both ECS and OBOGS, the systems that take

s

injected air and circulate

s

it

air

through the airplane and into the pilots' breathing regulators

, keeping the cabin dry and pressurized and the masks free of contaminants

.

ECS uses air from the engine intake and cleans out any

debris

moisture that would harm pilots or the instruments in the jet, before passing some into the cockpit for pressurization and the rest into OBOGS to be purified for breathing air.

If those stars don't align, it can spell trouble.

NAVAIR's efforts have flown mostly under the radar,

both in the public discussion and

even in the fleet, where some junior officers are out flying and suffering from oxygen loss but

experiencing events but

completely unaware that big Navy is working on improvements.

In the meantime, aircrew are relying on the back

-

up breathing system, which is a bottle of liquid oxygen stored under their seats. If something goes wrong, they pull the green ring on the system, which switches their regulators from OBOGS to that temporary supply.

NEED TO DESCRIBE HERE BRIEFLY HOW THE BACKUP SYSTEM WORKS

The issue burst into public view in

That confusion was driven home for some in early

February, when a lawmaker pressed Manazir for answers on how the Navy was addressing the alarming rise in hypoxia.

Rep. Niki Tsongas, D-Mass., hammered air warfare director Rear Adm. Mike "Nasty" Manazir and tactical aircraft program office director Rear Adm. Michael Moran on the steady rise of physiological episodes during a hearing of the House Armed Services Committee in February.

"It is, I think, an issue that despite all your investments and policies and training and everything else … the numbers still don’t go down," said Rep. Niki Tsongas, D-Mass., at the House Armed Services Committee hearing.

She added that

Jets need a better back

-

up oxygen system, as the current bottle buys a pilot 20 minutes if they're really calm; that could be three minutes if they're freaking out. Tsongas also suggested an automatic back

-

up oxygen

WHAT

system similar to that used by the Air Force.

and maybe three if you're freaking out.

Officials say that's tricky because the bottle fits under the seat, and there's only so much room to make it any bigger. And they assured her that the problems are under control.

Tsongas suggested an automatic system like the Air Force uses, but the admirals assured her that the oxygen bottle system hasn't failed yet and that the problem is under control.

Manazir cited his vast experience in fighters as an example.

"I’ve been flying Navy airplanes since 1982 on oxygen," testified Manazir. "I commanded an F-14 squadron that had OBOGS back in 1998. I have two cruises on that system and I have four cruises on the Super Hornet. I’ve never experienced a hypoxic event."

He went on to assure the congresswoman that

If the Navy were concerned about the safety of the jets, he added, they would ground the fleet.

But inside ready rooms, his

bluster

comments landed like a ton of bricks.

"We have definitely upped the reporting since 2010 and it is a huge issue for us," the East Coast pilot said. "In my opinion, the admiral is just lucky that he has never had an incident."

The West Coast pilot shared that disappointment.

"I have a concern. I have a huge concern. Lots of guys have concerns. That’s the perfect time to go, 'We have a problem and we need the funding to get it fixed,' " he said. "If that’s for a media comment, then I get it. But if that’s what he’s really thinking, then I’m disappointed."

According to a February "top ten" system safety concern survey of the Super Hornet and Growler communities, OBOGS reliability was the top concern out of 100 options.

the pilot said Manazir.

The pilot also pointed out that Manazir's timeline suggests

puts

his first 16 years flying were with liquid oxygen pumping into his mask, a system which OBOGS replaced.

"I would say, go to his log book and take all of the LOX flights out of there, and those numbers are going to come way down," he said. "We’ve got guys who have never been hypoxic, and guys who have been multiple times."

Manazir summed up the Navy's dilemma with an apt comparison.

"It's like chasing a ghost: You can't figure it out, because the monitoring devices that do this are not on the airplane," he said.

'The diagnostic machine'

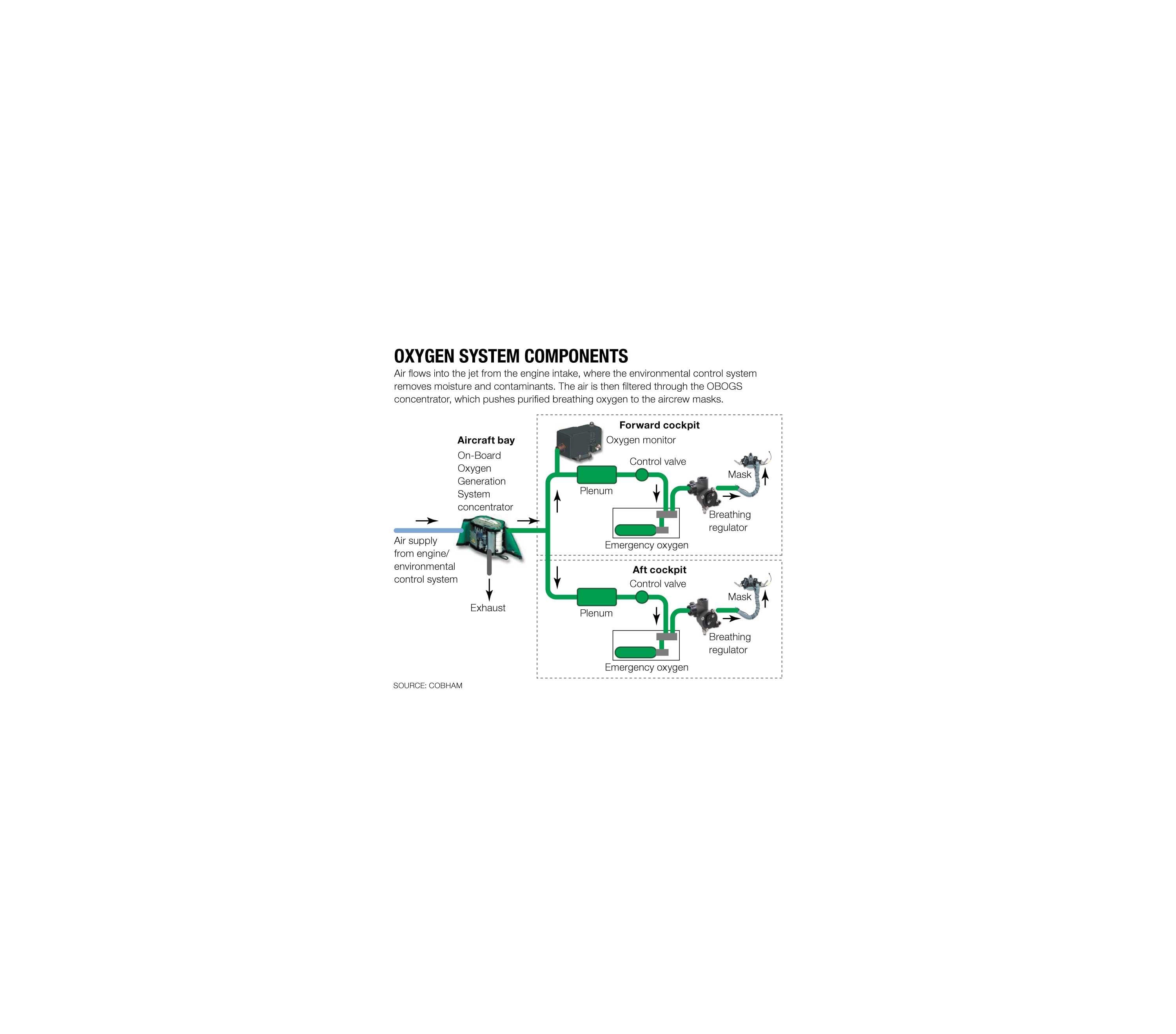

Air flows into the jet from the engine intake, where the environmental control system removes moisture and contaminants. The air is then filtered through the OBOGS concentrator, which pushes purified breathing oxygen to the aircrew masks.

Photo Credit: COBHAM

The Naval Safety Center is the service's central repository for reported

safety center keeps close track of

physiological episodes, which range from

include everything from

loss of oxygen or air contamination to black-outs from G-Forces, and in

t

one case, an MH-60 Seahawk aircrewman who severed his finger during a hoist. For

the purposes of

this story, Navy Times zeroed in on

those of

the more than 750 Navy and Marine Corps reports

provided to include only the instances

of hypoxia, decompression sickness, loss of pressure and warnings or failures of OBOGS and ECS since 2009.

In interviews at their Naval Air Systems Command headquarters, engineers and program officers said they're hard-pressed to find patterns

Data shows very few patterns for physiological episodes

.

"In general terms, it looks like the legacy Hornet [F/A-18 A-D] is seeing more ECS problems. Now, would you expect that from an aging airframe? You might," said Capt. David Kindley, program manager for the F/A-18 and EA-

=

18G Growler. "With the Super Hornet — more OBOGS."

There are also some patterns for which types of failures happen at which times, but it's not exact, said OBOGS lead engineer Dennis Gordge.

"If he’s just taking off, it’s probably an impurity in the breathing gas," he said. "If he’s been flying a while, it might be a fatigue issue. If he’s having some pressurization problems in the aircraft maybe an hour into it, that’s probably more of an ECS problem."

Though not necessarily. For the East Coast pilot, the jet warned of an OBOGS degrade about two hours into a seven-hour flight over Afghanistan. It was a low-altitude flight at that point, so rather than pull the emergency oxygen and abort the mission, the pilot shut off OBOGS and breathed through the cockpit.

However, later in the flight the pilot ascended and reactivated OBOGS, which failed again, on the way back to the carrier.

"We were probably still 30 minutes from landing," the pilot recalled. "While we were overhead the ship in the stack, waiting to come aboard, I started to lose my peripheral vision and my face felt flush and my heart started pounding."

Breathing emergency oxygen, the pilot was told to hang back in order to do a straight approach onto the flight deck, a safer option under duress.

"Bottom line is, I had two very scary wave-offs and then I trapped on the third pass. My emergency O2 ran out while I was still airborne and I don't even remember seeing a ball on the lens," the pilot said, speaking of the heads-up display guide that shows pilots their landing trajectory.

Aircraft have built-in sensors to warn when a system is failing, like if the OBOGS itself isn't working. But if it's not filtering out contaminants properly, or if it's not pumping out enough air, there's no warning for that.

"The problem with these kinds of episodes is, the diagnostic machine — that is, your brain — is the very thing that’s being impacted," Kindley said.

NAVAIR has been working on a sensor for about eight years, Gordge said. When asked why OBOGS wasn't developed with it, he couldn't be sure.

During development of the T-45C Goshawk fighter training in the 1980s, he recalled the question of a diagnostic sensor coming up during the critical design review.

"And the fleet representative said, 'No, I'll know the system's broken when I can't breathe,' " he said.

Developing the sensor has taken time and money, and NAVAIR doesn't want to replace what it's using unless they know it's a better option, he added. It's scheduled to go online in 2017.

In the meantime, his team has overhauled the molecular sieve inside the OBOGS concentrator, where air is sucked in and purified before it reaches a pilot.

The sieve is a sand-like material that traps nitrogen and pumps oxygen and argon, a harmless gas, into the aircrew regulators. It's very efficient, Gordge said, and can be cleaned and reused a few times before it needs to be replaced.

However, the sieve the Navy bought for OBOGS back in the 1990s isn't manufactured anymore, so in recent years they scouted out a mix of two newer materials, Gordge said, and those have been changed out in over 300 aircraft so far, with priority going to deploying squadrons.

OBOGS is really good at making unlimited oxygen because it pulls from outside air, which for the Navy is a step up from the old school liquid oxygen supplies, which limited flight times and required time and money to keep stocked.

The hitch, however, is that those long flights put more stress on the components, and OBOGS is only designed to filter clean, dry air. If there's something else in the concentrator, there will be problems.

"Oxygen levels are not usually the problem," Gordge said. "Contaminant is usually the issue."

That includes carbon monoxide, a deadly gas which is released when moisture hits the system.

"On a

cat

[catapult] stroke, you have steam ingestion right down the intakes," said the West Coast pilot. "There’s your moisture. Now you've got guys come off boat getting CO hits."

A new carbon catalyst in the concentrator is addressing this, Gordge said, to clean out any toxins.

Working backward, from the regulator to the air intake, NAVAIR has also made dozens of changes to ECS. Twenty-eight components of the system have caused physiological events, said NAVAIR ECS expert John Krohn — 25 of those were improved, and the other three were one-offs.

Many of those components were designed as "fly-to-failure," he said, but now the system goes into depot maintenance based on 400- or 800-hour flight limits and gets an inspection and replacement whether it's broken or not.

Still, ECS's main function is to take water out of the humid ocean air in the carrier environment, not to take out contaminants. If a toxin is water soluble and makes its way in, it'll stay there when ECS removes the moisture.

Or in some cases, normal operations get in the way. The Navy does aerial refueling, Gordge said, and the boom goes right next to the engine's air intake.

"Nowhere in the OBOGS design specification did it allow you to pour raw fuel into the OBOGS, but it happens," he said.

'Bad air'

The On-Board Oxygen Generation System includes a monitor, a black box seen at lower right in this F/A-18E Super Hornet, that triggers an alarm when the system stops sending oxygen to the aviator's regulator. Officials are also working on cockpit sensors that will detect low oxygen levels and any contamination in breathing air.

Photo Credit: MC3 Bryan Mai/Navy

Without a sensor to tell the aircrew what's

exactly is

going wrong, they must

it's up to them to

diagnose themselves, and then

up to

NAVAIR engineers must diagnose their equipment.

Pilots and NFOs are required to get hypoxia training every year, with a spin in an oxygen deprivation simulator every other year. This way they become experts at spotting

reading

the signs in themselves and others.

That's key because the guy flying the plane might not realize what's happening. The West Coast pilot told the story of a pilot doing an acceptance flight for a new jet, who got home safely but felt like something wasn't right, so he looked at his cockpit video recording.

"He talks all the way through what he’s doing. He stops talking for five minutes, just completely stops," he said. "And then five minutes later, just picks up where he left off. He doesn’t remember those five minutes at all."

In some cases, the pilot will feel sick but the NFO won't, or one will feel effects after landing and the other won't. The other complication is that the issues can be fleeting.

"One of the problems we have with a lot of these is, the body does a really good job of cleaning itself up," Kindley said. "The same is true of the airplane."

There may be no symptoms with either after the flight, which makes it hard to diagnose.

One of the pilots had a suggestion for those feeling hypoxia symptoms:

The West Coast pilot has a tip for that. If you think you're hypoxic,

First, follow procedure and pull the green ring to stop the airflow and activate the backup oxygen.

"Then if you have the wherewithal, if you turn the concentrator itself off, whatever bad air was in there, the engineers can see it," the West Coast pilot said. "If you don’t turn it off, it continues to cycle, and the engineers might say they see great air."

Aviators are often reluctant to report what seem to be health issues for fear of jeopardizing their flight status. Still, self-diagnosis and reporting is up, according to both pilots and officials.

"Most of the guys have the hair trigger now that if something’s not right, I’m pulling the green ring and I’m going back," the West Coast pilot added. "But that wasn’t always the case."

Though officials say the awareness ist out there, pilots say it doesn't always filter to the more junior ranks.

"Guys in the squadron are talking about it because leaders are talking about it," the pilot said. "We don't have an email from the air boss or the [air wing commanders]CAGs."

NAVAIR is planning to visit

's team is planning to has set up road shows to

major air stations to talk about what they're doing to improve the systems. But some fliers are fed up.

but there is still a frustration with how long it's taking to get to the fleet.

"Seven years is unacceptable to try and figure out what’s going on and to try and get it fixed," the pilot said. "Really? A couple more years? So now we’re looking at 10 years."

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.