Pinning on the fouled anchors of a chief petty officer is, for many, the crowning achievement in a sailor's career. The lore of advancing into the Navy's chiefs mess is unlike any other enlisted advancement in the military.

Each summer, a chiefs selection board convenes and culls through the records of thousands of first-class petty officers, looking for the Navy's next generation of senior deckplate leaders.

Navy-wide, the advancement rate is about one in four. This year's board, which started deliberations on June 26, has quotas that will advance eligible E-6 sailors at a rate of about 23.6 percent. The results will be published in August.

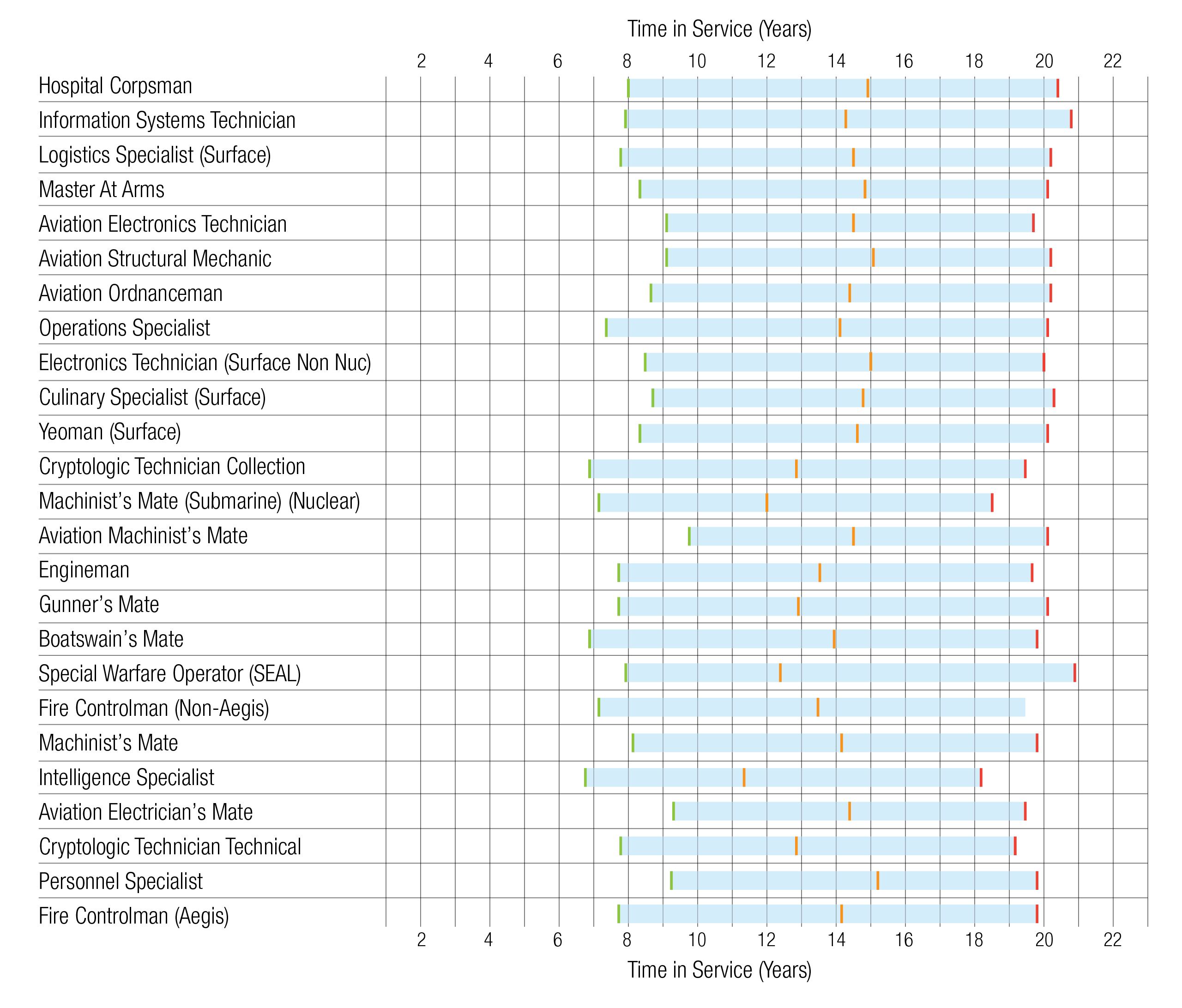

On an individual level, the average sailor makes chief petty officer in just under 14 years of service after spending an average of about six years as a first class petty officer.

Yet the statistics for individual ratings fluctuate depending on the health of each rating. For a high-demand career field like Explosive Ordnance Disposal, sailors make chief in less than 12 years on average. Meanwhile, for a more competitive rating like Personnel Specialist, it takes on average more than 15 years.

And within the individual ratings, the path to the chiefs mess varies a lot. Some sailors advance very quickly, potentially making chief in less than seven years. Others take more than 20 years to make the cut near the end of a career, when they are dangerously close to being shown the door because of up-or-out limits.

A detailed look at the Navy advancement data can help sailors calibrate their hopes and expectations.

How long does it take to make chief? The average, minimum and maximum time in service it takes to make chief petty officer for the 25 most populous ratings. How does your rating stack up to the rest?

The E-7 selection board is by far the largest of any Navy board. The advancement rate varies over time. Since 1997, selection rates have averaged 22 percent, with a high of over 28 percent coming in fiscal 2002 and a low of about 12 percent in fiscal 1998.

Fastest to chief

Since 2011, there have been three sailors who ahve advanced to chief petty officer in under six years. And in each case — an intelligence specialist in 2011, an operations specialist in 2012 and a damage controlman in 2015 — they did it with under three years time in grade as a first class.

The latter sailor, Chief Damage Controlman (SW) Jose Rosario, was notified he'd been awarded his chief's anchors in August 2015. When the word came down, he had five and a half years in the Navy, and was still under six years in when his official advancement date arrived four months later.

"Being a chief is tough and it doesn't matter if you make it in five or 19 years," Rosario told Navy Times in a recent interview. "But remember, you aren't doing this yourself."

Sure, the stars aligned in a way for Rosario to achieve the milestone in less than half the time it takes the rest of the Navy, but that doesn't mean it was simply gifted to him.

Rosario credits hard work, exhausting study and plenty of good mentorship as the reasons he made chief petty officer in record time.

And he did so despite experiencing failure, too.

Rosario made E-4 after being meritoriously promoted for finishing on top of his A school. But his first time taking an exam and competing against his peers for E-5, he missed the mark by 5 points.

The next cycle, he sewed on second class and has not looked back since.

Normally, a sailor has to wait three years as an E-5 to test for E-6. But the rules allow COs the ability to waive a year for sailors who get "Early Promote" recommendations on their evaluations.

Twice, Rosario competed a year early for the next paygrade, first putting on E-6 and then chief petty officer, each on the first try.

Hard work and studiousness are ultimately the only things in a sailor's control that will ensure being in position for advancement.

The best shot

What sailors can't control is the Navy's allotted opportunity, or more simply, the percentage of sailors in a given rating and paygrade who will advance during a cycle.

The good news is that over the past five years, only once has a rating had zero chance to make chief. That was the SeaBee rating of engineering aid during the fiscal 2012 board.

Navy officials are constantly reminding sailors that advancement is vacancy-driven. Each year, the number of vacancies in ratings and paygrades fluctuates.

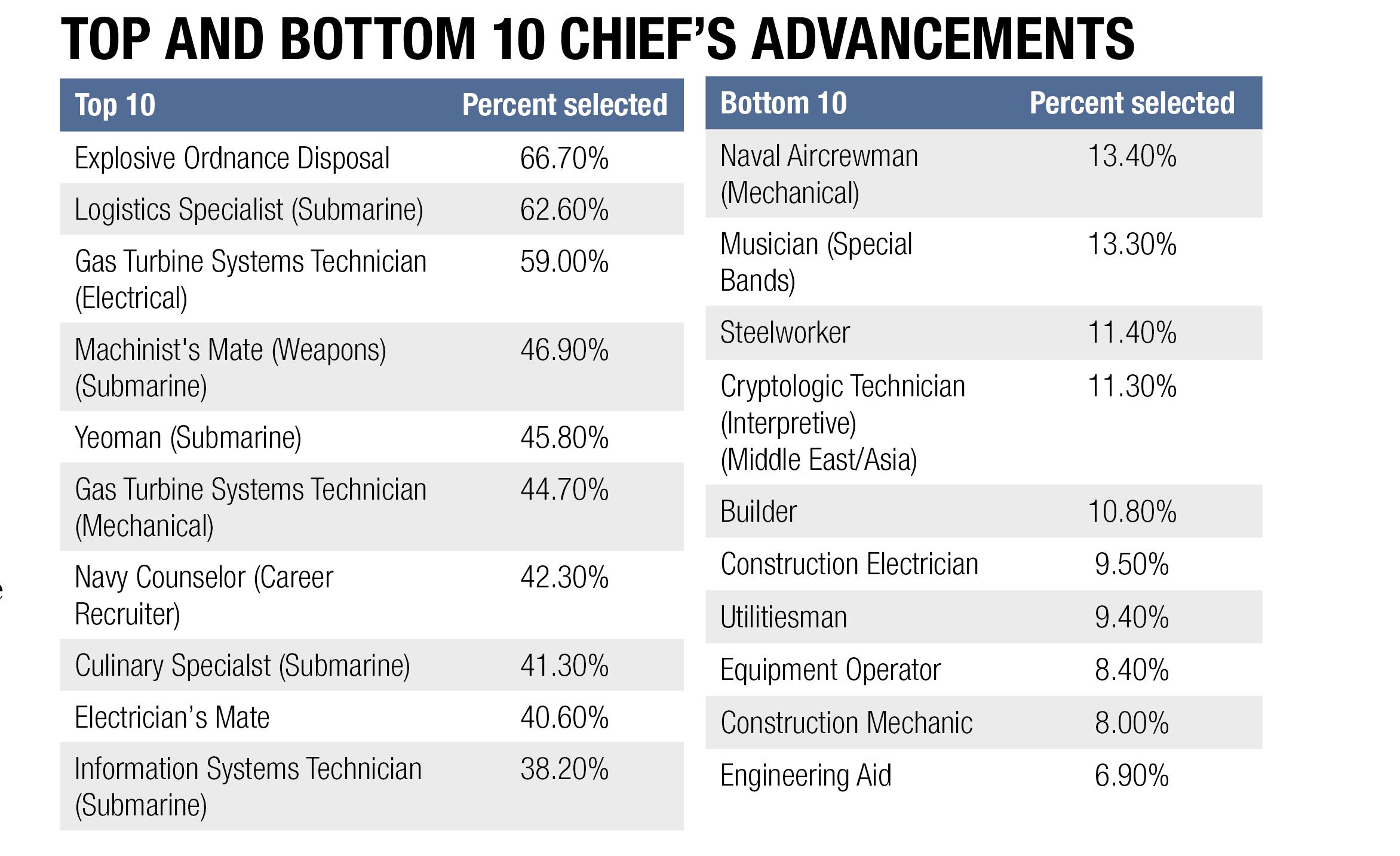

Over the past five years, no rating has had consistently higher opportunities to make chief petty officer than explosive ordnance disposal, which has advanced 66 percent of their eligible first class petty officers.

Interestingly, the EOD rating never had the highest opportunity in any year during the aforementioned five-year span. The rating's year-to-year consistency at the top of the pack, however, is why it comes out on top.

Half of the top 10 most opportunistic ratings were from the submarine community — logistics specialists, machinist's mate (weapons), yeoman, culinary specialists and information systems technicians.

When it comes to the least opportunistic ratings, that unfortunate distinction goes to those in the SeaBee community, where all seven ratings reside in the bottom 10.

The top and bottom 10 ratings for advancing to chief.

The reason for this is simple — the Navy's construction battalions were cut by over one-third in the past few years. But good news is on the horizon for these sailors. With the exception of the construction mechanic, all of the Seabee ratings are seeing a significant boost in opportunity to make chief petty officer this year.

Fast-track ratings

When it comes to ratings, on average, that have advanced faster to chief petty officer in the past five years, that crown belongs mostly to the surface and submarine nuclear power sailors.

All of the nuclear power ratings advance to chief between 10 to 12 years of service, while spending between four and a half to six and a half years as a first class.

Once again, EOD fares well, coming in fifth place in terms of lowest average time to make chief —11.2 years — making it the only rating to be in the top-10 for both opportunity and fastest time to put on anchors during the five-year span.

Where it starts to get even more interesting, though, is looking at the top 10 ratings that consistently advance sailors to chief petty officer in the least amount of time during the past half decade.

This list, too, contained only one rating among those with the best overall opportunity — submarine sailors in the machinist's mate (weapons) rating, who are making chief, on average, at just under seven and a half years time in service.

Even Rosario's damage controlman rating ranks 33rd in average time to make chief — 13 and a half years of service. And even with Rosario's record-setting five and a half years to chief, DC still sits 23rd overall in the five-year average minimum time in service category.

What this suggests is that although the rate of opportunity typically plays a heavy role in advancement, any sailor can beat the odds.

Don't give up, ever

Until the Navy's recent announcement that E-6 sailors will be allowed to stay beyond the 20-year active duty mark, first class petty officers reaching that threshold were required to retire.

But the data show that the Navy makes exceptions to those rules, often granting waivers for rating or operational needs.

In those cases, many sailors, who have often waited between 10 and 15 years as first class petty officers before putting on anchors, have seen their dreams realized at the last minute.

In the past five years, two sailors have made chief petty officer with over 22 years on active duty, and another seven have made the cut after over 21 years.

In all, 142 sailors have transitioned into the chiefs mess at or over the 20-year mark, with 122 having at least 21 years in when they were advanced.

According to Master Chief Machinist's Mate (SW) Damian Kelly, who is currently on board the command ship Mount Whitney, waiting nearly a decade to become chief isn't any indicator of how a sailor will advance further up the ranks.

Kelly's wait for chief ended at his 19-year mark, on his second-to-last chance before being forced out due to high-year tenure.

The advancement was unexpected — he and his wife had already bought a home in Wisconsin to prepare for life after the Navy.

After being selected for chief petty officer in 2009, Kelly advanced to E-8 and E-9 during the first opportunity for each. He's now looking forward to at least a 30-year career.

There's no shame in making chief later in a sailor's career, Houlihan says, because seasoned sailors make the Navy even stronger.

"These are some very valuable members of our chiefs mess, because they have many years of experience and nearly always hit the mess ready to make an immediate impact on their rating and the command," he said.

"A lot is to be said for someone who has stuck to it and pushed and pushed and not given up — that attitude of resilience really defines our chiefs mess."

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.