Readiness among the crews of Japan-based cruisers and destroyers has plummeted in recent years, leaving nearly 40 percent of crew warfare certifications expired as of June, according to a government watchdog group slated to testify before Congress Thursday.

More than two-thirds of the lapsed crew certifications — including those for mobility-seamanship and air warfare — had been expired for at least five months, according to a copy of a Government Accountability Office testimony to Congress obtained by the Military Times.

“This represents more than a fivefold increase in the percentage of expired warfare certifications for these ships since our May 2015 report,” GAO Defense Capabilities and Management Director John H. Pendleton’s testimony read.

The Navy’s Japan-based 7th Fleet has been the target of scrutiny and criticism since the August collision of the destroyer John S. McCain with an oil tanker, which followed the Fitzgerald’s June collision with a cargo ship.

In total, 17 sailors died in the McCain and Fitz disasters. The commanding officer for 7th Fleet was relieved of command shortly after the McCain collision.

RELATED

Pendleton is slated to testify before the House Armed Services Committee’s Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee Thursday afternoon. The testimony is based on ongoing GAO research of Navy readiness that began months ago before the two fatal collisions put 7th Fleet under a microscope.

An advance copy of the testimony warns that the Navy faces a difficult future of concurrent priorities.

The Navy must fix today’s readiness and maintenance problems, address the lack of training time for crews forward-deployed overseas, while also attempting to grow, man and fund a larger fleet.

At the same time, western Pacific threats — like an emerging Chinese navy and a belligerent North Korea — loom large.

Ships that are home-ported overseas in places like 7th Fleet face a higher operational tempo than their U.S.-based brethren, and the GAO notes that other priorities have fallen by the wayside.

“GAO found in May 2015 that there were no dedicated training periods built into the operational schedules of the cruisers and destroyers based in Japan,” the testimony states. “As a result, the crews of these ships did not have all their needed training and certifications.”

While the Navy has drawn up plans to revise schedules to provide 7th Fleet sailors with dedicated training time, “this schedule has not yet been implemented,” according to the GAO testimony.

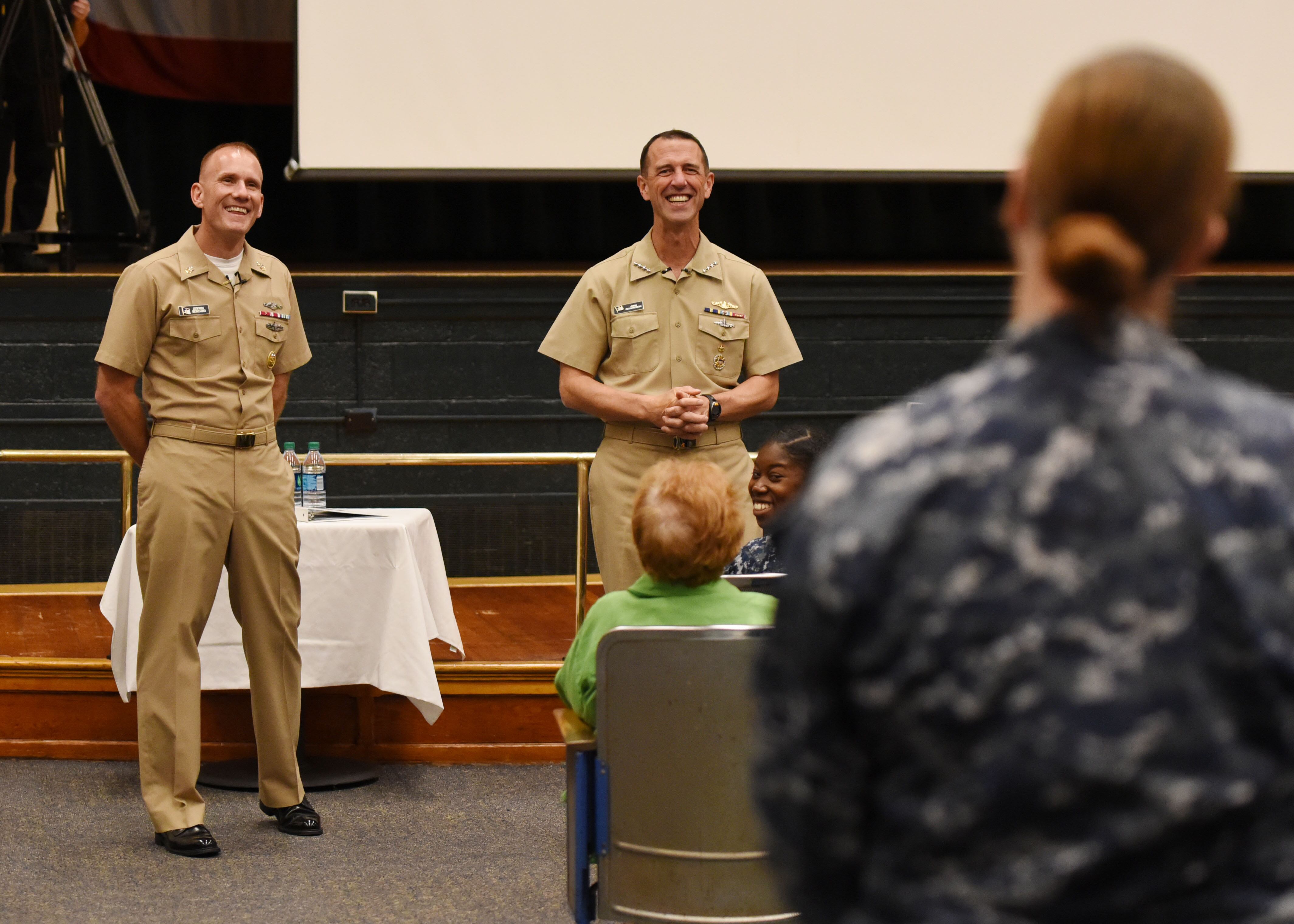

In a Facebook Live appearance last month, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson decried the sea service’s reliance on doing more with less, and said that needed to change.

RELATED

But how that can happen in the near term remains unclear on several fronts.

The GAO notes that crew reductions enacted in the early 2000s “were not analytically supported,” and that some sailors now work more than 100 hours a week, creating potential safety risks.

The Navy’s current 277-ship fleet is down from the 333 ships the Navy had in 1998, but the number of ships deployed overseas has consistently remained at about 100 vessels, meaning individual ships are deployed more to maintain the same level of presence.

Forty ships are home-ported overseas today, up from 20 in 2006, according to the GAO.

Those permanently deployed ships “do not have designated ramp-up and ramp-down maintenance and training periods built into their operational schedules,” the testimony notes.

Such vital maintenance is done via shorter, more frequent maintenance periods, or put off entirely for up to a decade until the ship returns to a U.S.-based homeport, according to the GAO testimony.

The relentless operational demands placed on those overseas crews means there is no dedicated training time for sailors, resulting in a “train on the margins” approach, the testimony states.

The GAO recommended the Navy develop a sustainable operational schedule for ships based overseas, and the Defense Department reported in 2015 that such a schedule had been developed.

But Pacific Fleet officials told the GAO such revisions were still under review.

The GAO testimony focuses on the certification of ship crews to perform certain operations. For example, aircraft carriers get certified for fixed-wing flight deck operations or rotary-wing flight deck operations. Warfare qualifications for individual sailors never expire.

While today’s crews are being overworked, there is nevertheless widespread talk in Washington about growing the fleet to a new target of 350 ships. A growing fleet would require more sailors, and the GAO warns that a funding source for growing the ranks remains unclear.

The Navy’s current crisis comes at a time when the sea service expects to be contested by conventional naval forces in the future, a challenge to its dominance of the seas not seen since the Cold War.

Still, the Navy’s problems are not unique, the GAO notes.

America’s military branches “are generally smaller and less combat ready than they have been in many years,” according to the testimony.

Each branch has had to cut training, modernization and maintenance due to budget restraints, all while while fighting continuous conflicts worldwide since 2001.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.