It’s official: The Navy is growing.

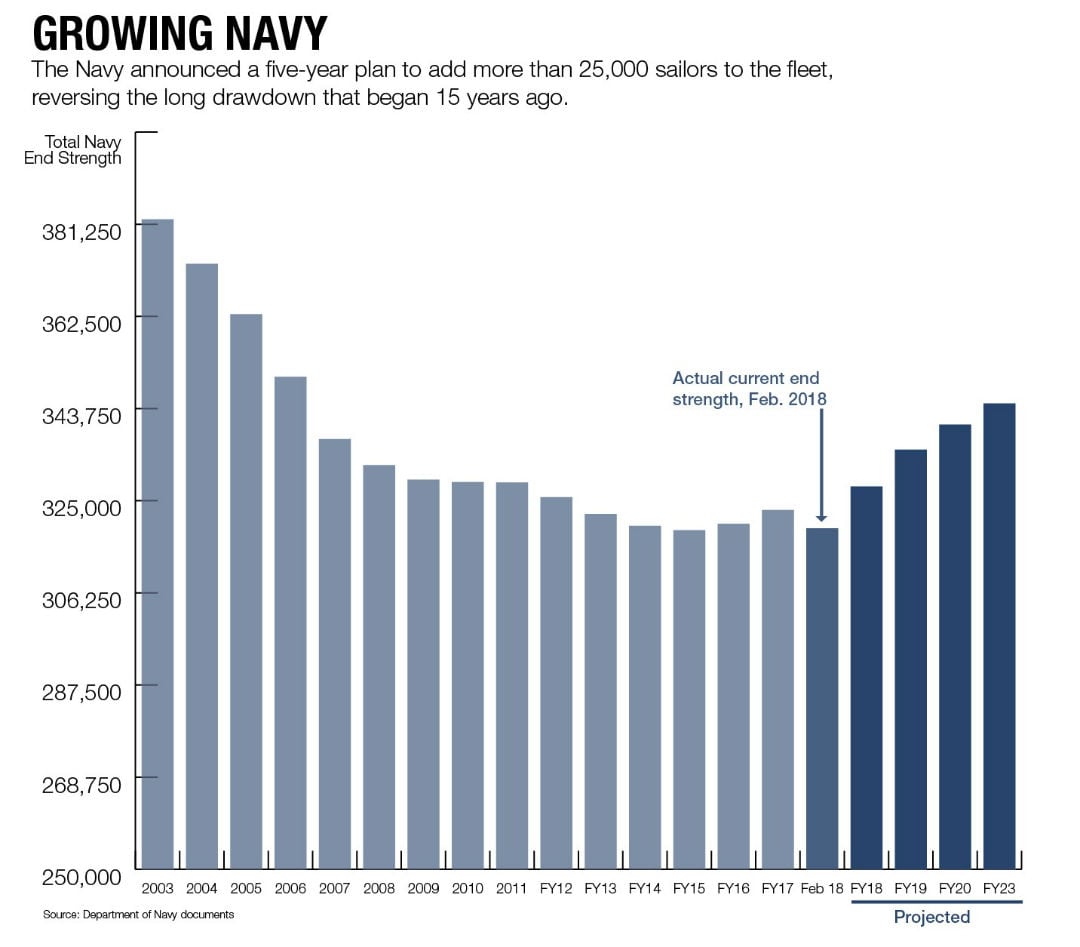

The Pentagon has unveiled a five-year plan to add more than 25,000 new sailors to the fleet, putting today’s Navy on the cusp of massive growth that will impact advancement, retention and other career opportunities across the force.

When the Defense Department released its budget request for fiscal year 2019 on Feb. 12, it included detailed plans for building a bigger fleet by expanding the enlisted ranks and offering millions of dollars in added bonuses.

The need for more sailors is driven by plans to build dozens of new warships. Currently, there’s 280 battle force ships, and that’s slated to grow by 46 by the end of ’23, when the ship total is expected to stand at 326 — the highest totals in nearly 20 years.

In short, it’s a good time to be in the Navy if you want to move up.

“Our force structure is expected to grow as we build the Navy the nation needs, which will require increasing end-strength. As we grow, our need for highly talented people increases,” Vice Adm. Robert Burke, the chief of naval personnel, told lawmakers on Feb. 14.

The writing was on the wall in December when Navy personnel officials made several changes that were designed to make it easier for sailors to stay in the ranks.

Among the moves was increasing high-year tenure for petty officers, offering voluntary extension programs that bypass traditional re-up approval and even stopping mandatory discharges for fitness failures.

But now it’s clear that this build up is likely to last for years.

The service’s current end strength stands at just 319,400. That’s slated to grow as high as 326,800 this year, and to 335,400 by the end of FY19. The five-year plan calls for adding a total of 25,400 sailors to reach a total end strength of 344,800 sailors by the end of fiscal year ’23.

The Navy hasn’t seen manpower like this since 2006, when the service finished the year at just over 350,000.

The end-strength requirement could grow beyond 350,000 if Washington finds a way to fund the Navy’s long-term goal of building a fleet with more than 350 ships, Burke said.

“Our end strength profile is largely determined by the composition and manpower needs of the fleet and the timing of delivery of those platforms,” Burke wrote in his Feb. 14 written testimony to Congress.

“Manning the fleet may require an end strength increase approaching 350,000, fully dependent on the required supporting units and squadrons, and training pipeline growth.”

GROWING OPPORTUNITIES

Adding that many sailors will not be easy. The civilian economy is good. Interest in military service has flattened among today’s young people. And the Navy needs more skilled sailors than ever.

“We are clearly in a war for talent,” Burke told the committee. “The propensity to serve is declining and each of the services, as well as the civilian sector are vying for the same talent pool.”

There may be tough times ahead for military recruiters, Burke said.

“We just made our FY17 targets,” he said. “This year’s trajectory is good, but we will require steady and reliable funding going forward to stay on track.”

The Navy is asking for a massive increase for enlistment bonuses to entice new recruits to pack their bags for Great Lakes. The budget request seeks more than $90 million, a two-fold increase from last year’s budget of less than $30 million.

Meanwhile, the Navy is putting more recruiters on the street. Burke said he plans to add 226 sailors to both the fleet recruiter force as well as the career recruiting force over the next five years.

The goal for next year is to bring in 39,900 raw recruits, a nearly 10 percent increase from this year’s target of 36,600.

Burke acknowledged the significant recruiting challenges on the enlisted side, but he said the Navy is not seeing similar problems with officer recruiting.

“We continue to see strong interest in commissioning opportunities through both the U.S. Naval Academy and Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps program,” Burke wrote. “The number of highly qualified applicants vastly exceeds the number of available appointments.”

RETENTION

Just bringing in new E-1 sailors and ensigns, however, will not grow the fleet fast enough. So the Navy is also planning a big expansion of retention goals.

“Production of new sailors will be largely limited by first-term sailor training capacity, making retention of every capable sailor critical to operational readiness as the Navy grows,” Burke said.

Overall, retention remains high, but with new manpower goals, Burke sees difficulties on the horizon.

“Labor market factors may pull sailors with critical skills into the civilian job market,” he said.

That’s why the Navy made recent policy changes to stem attrition in the ranks.

The Navy is eliminating early outs and adjusting upward the high-year tenure “up or out” caps for sailors in pay grades E-3 through E-6.

The service also stopped kicking out sailors with too many fitness failures on the books, allowing them to finish their current enlistments and giving them a path to stay in longer.

The service is also expanding re-enlistment and rating conversion opportunities. The Navy’s list of overmanned ratings has declined in recent months, opening more ratings to automatic reenlistments.

But even these measures may not be enough to keep skilled sailors in the ranks.

“In light of growth anticipated in the coming years, we expect most ratings will find it difficult to continue achieving required retention [levels] — nuclear field, special warfare, advanced electronics, aviation maintenance and information technologies retention require focused efforts,” he said.

On the officer side, the Navy is facing the challenge of keeping aviators, nuclear-trained surface warfare officers, submarine officers and Naval Special Warfare officers, specifically among Navy SEALs.

ADVANCEMENT OPPORTUNITIES

Navy officials often say the service’s advancement system is “vacancy driven.” This means advancement opportunity is dependent on the number of open billets at the next paygrade level in each rating.

Navy budget documents show growth will happen mostly at the E-5 and E-6 levels.

The Navy wants to grow the ranks of 2nd class petty officers by nearly 10 percent, adding more than 6,400 billets next year to this year’s end strengths of 63,679.

Getting advanced to 1st class petty officer will also become easier as the Navy adds 2,447 new billets to this year’s E-6 end strength of about 46,000, an increase of about 5 percent.

In the enlisted khaki ranks, the growth isn’t quite as notable, but there’s slated to be 220 more chief petty officers, a slight uptick from this year’s force of about 21,500 chiefs.

Next year, the Navy will add 195 new senior chief billets over the 2018 end strength of nearly 7,500, as well as 122 more master chiefs, up from 2,644.

But officials say this may not translate directly to more advancements. Some of those new slots could be filled by granting sailors high-year tenure waivers and allowing them to stay in their current rank beyond their projected loss date.

Still, depending on the rating, a growing Navy will most likely have growing advancement opportunity, possibly as early as this year. That’s because those planning advancement quotas predict out at least a year and sometimes more.

INCENTIVES TO STAY

The Navy will target sailors with critical skills with additional incentives.

Special and incentive pays continue to play a vital role in retaining sailors in high-demand skills, Burke told lawmakers.

The ‘19 budget increases the money for initial selective reenlistment bonus contracts by 20 percent, putting an additional $37.7 million in sailors’ pockets.

The Navy has wasted no time in updating its SRB offerings, adding 39 skills in 24 ratings to the bonus eligible list on Feb. 15.

Officials increased one other skill level and refrained from reducing or eliminating any offers.

Rules were also reworked to allow for earlier re-ups, making it easier for sailors to cash in.

“Targeted bonuses continue to be the most cost effective monetary tool in addressing retention challenges,” Burke said. “But we are aggressively applying a combination of monetary and non-monetary incentives with good effect.”

This means that the process of “negotiating orders” is rapidly becoming a true negotiation for sailors, he said.

The Navy is changing the current orders negotiation website into something resembling LinkedIn, which, Burke said, allows more of a back and forth between sailors, commands and personnel command in fitting sailors to their next jobs.

It’s these negotiations that may determine whether some sailors stay or go.

For example, the Navy might have most need for sailors with a specific set of skills at a command in a homeport rather than where that sailor is currently stationed.

But in cases like that, the sailor may have a child in high school and wants them to graduate there, or a spouse or has a particularly good job requiring proximity.

Burke says it’s not always possible, but it’s becoming more and more common that these discussions are playing a part in the retention decisions of sailors.

“The marketplace aspect to this is to view not just their orders but total next assignment in terms of a total compensation package, and geographic stability can be part of the conversation when it’s possible,” he said.

“Career progression, ship type, where those ship types are home-ported, where they are in their career, may make that impossible. But through use of those techniques, over the last two years, we’ve been able to increase the numbers ... up to around 25 percent of our next career moves have been seeing a home port [as an incentive].”

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.