Editor’s note: This story is part of a series looking at the effects of the Fitzgerald and McCain collisions on sailors, families of the fallen and Big Navy. To read more, go here.

One year after the destroyer Fitzgerald was gouged by a merchant vessel, flooding a living space and killing Noe Hernandez and six of his shipmates, Dora Hernandez walked those quarters.

It was June 17, the first anniversary of the disaster.

The 27-year-old widow joined several Fitz families who gathered in the Mississippi shipyard where the warship is undergoing repairs.

As Hernandez and other families of the Fitz fallen descended into the area, she was struck by how bare everything was.

“It was hard seeing her completely with her insides just out, exposed,” Hernandez said.

She had gone belowdecks before, while the stricken ship was still in Japan, along with her mother-in-law and a priest.

“We put holy water in the areas,” Hernandez recalled recently. “That was the first time I saw the berthing.”

Gone were the exercise bikes and lockers and mattresses that had been thrown about the quarters after the ACX Crystal gouged a 221-square-foot hole in the ship beneath the waterline and allowed the seawater to furiously flood in.

“It was so small,” she said. “I knew the spaces were so small and there were no racks left or lockers, but you could see the outlines of the racks.”

In the Mississippi shipyard this month, seven roses had been laid against the patched-up hole in the Fitz, she said.

They marked the loss of her husband, Tan Huynh, Gary Rehm, Dakota Rigsby, Carlos Sibayan, Shingo Douglass and Xavier Martin.

“All I could think was, this is where my husband was, and this is where Rehm was and this was where Martin was, and this was where Douglass was, and this was where Sibayan was,” Hernandez said.

One year later, back home near the small Texas town where she met her husband and fell in love with him, Hernandez said she still wonders why Noe wasn’t one of the shipmates who made it to the hatch and escaped to higher ground as the water flooded in.

No one had much time. Water hit their berthing’s ceiling in minutes and many sailors were asleep when the collision occurred at 1:30 a.m.

But Noe was a healthy 26-year-old, his wife recalled. He loved to work out “and he could swim for miles.”

“He still didn’t make it out,” Hernandez said. “That was the biggest thing for me. What were his last moments like?”

Noe was vigilant, his wife said. He couldn’t have been asleep.

Something must have slowed his escape.

“Maybe he tried to save his brothers,” Hernandez said. “He had everything except time and air.”

“They worked them hard”

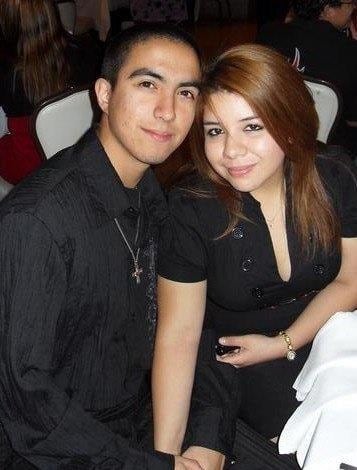

Noe (pronounced “No-ee”) and Hernandez grew up in Weslaco, Texas, a town of about 40,000 not far from the Gulf coast.

They met freshman year of high school in French class.

RELATED

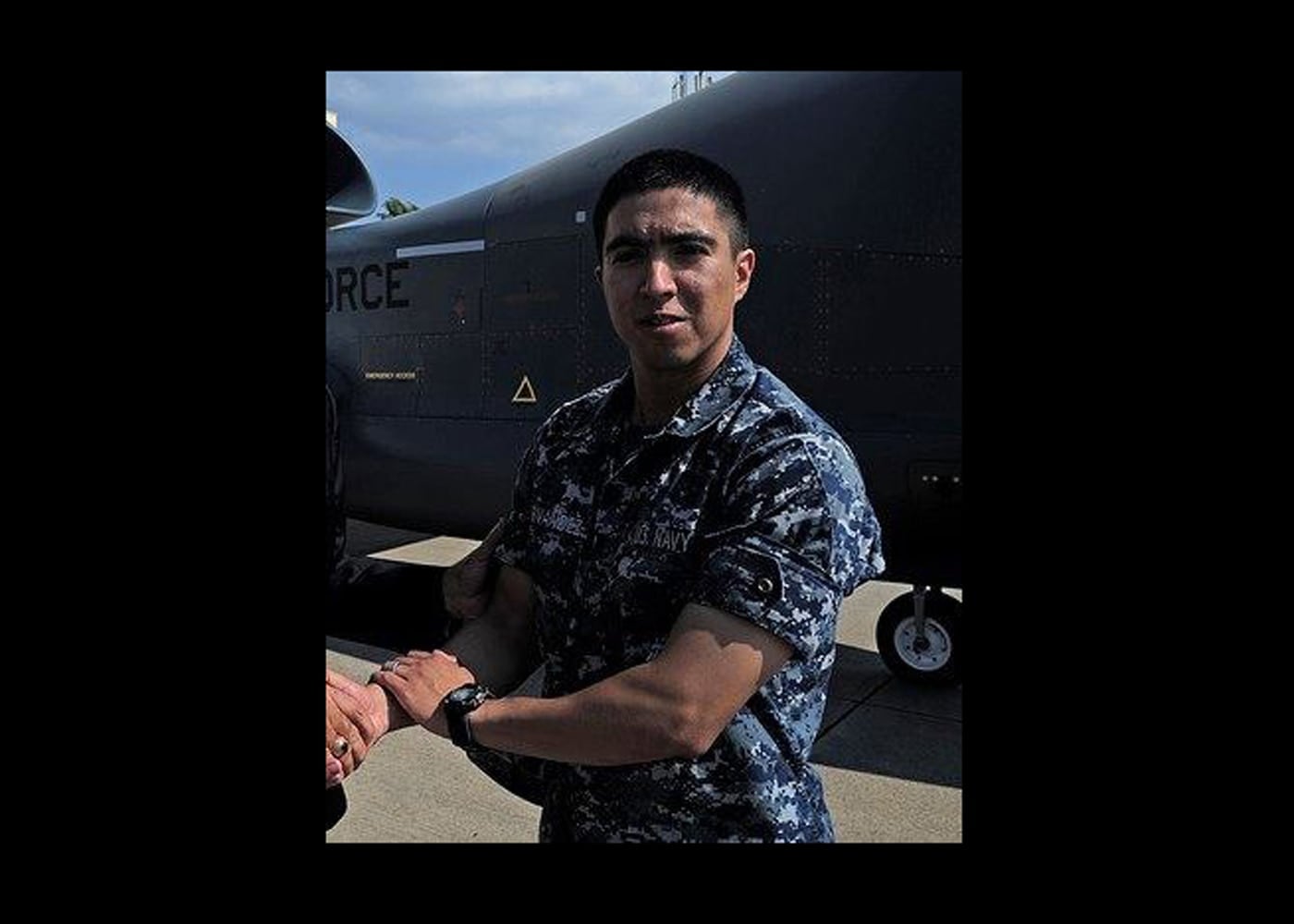

Noe was part of a JROTC program and walked the halls with a Navy backpack.

He knew he was going to enlist, Hernandez said, “and he was proud of it.”

Eventually, Noe took a shine to his future bride.

“He asked me out on his birthday, so I couldn’t say no,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez wanted to enlist herself, but Noe talked her out of it.

“He said, ‘I want to laugh with you and marry you. I’d rather have you by my side than worry about us being stationed together,’’ Hernandez said.

Eight years before his death, on June 17, 2009, Noe left for boot camp.

He got deployed to Italy and proposed to Hernandez when home on leave.

After he ranked up, Hernandez joined him in Italy.

They arrived in Japan in late 2015, and Hernandez said she loved it there.

“My husband was very proud to be on the Fitz,” she said. “He was proud of his ship and the crew.”

Japanese society was so polite, and the military community was an intimate and protective group, she said.

“He loved to travel and so did I,” Hernandez said. “We didn’t really drink or party or were into video games, we just traveled every time we had a chance.”

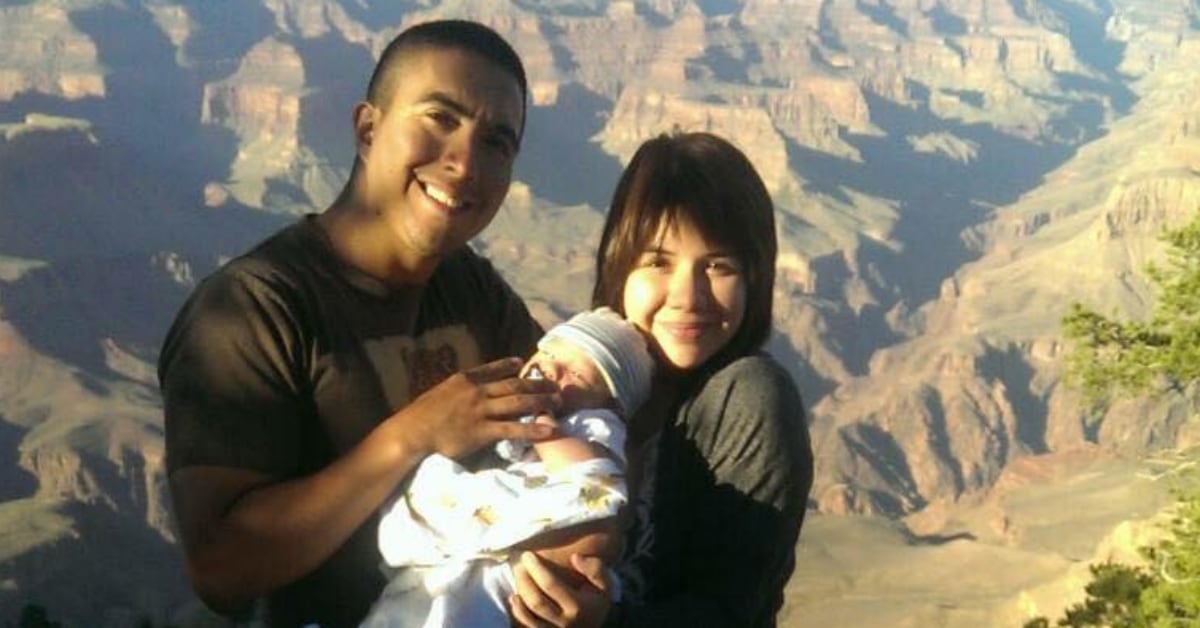

Their son was born, and Hernandez said that while she liked being in Japan, she grew to dislike the frenzied work tempo Noe endured with the Fitz.

The tempo in West Pacific’s 7th Fleet came under scrutiny after the Fitz collision, and even more so after the McCain suffered a similar fatal collision that killed 10 more sailors less than two months later.

“You get tired of working, and they worked them hard,” Hernandez said. “That was something he did talk to me about…they were always working, they were always pushing.”

Even when the ship went into drydock shortly after they arrived in Japan, the work did not relent, she said.

“They still had to stay long hours,” Hernandez said. “One of those mentalities was, this is how life is going to be on a ship, so get used to it now.”

Still, Noe loved being at sea and being with his shipmates.

“That’s not my husband”

When the spouse group messages started popping up about the Fitz collision that morning, Hernandez took a train to the base and went to an assembly for spouses.

Those who hadn’t heard from their sailors raised their hands and wrote their names on a list, she said.

One wife who hadn’t heard from her sailor was sobbing.

Hernandez stopped and prayed with her.

“She stopped mid-prayer and she got a phone call,” Hernandez said. “it was her husband calling. I got really excited for her.”

Later, Hernandez was told that Noe was one of the missing sailors.

She went out to the pier, where the crippled ship was moored.

Hernandez waited overnight on that pier, from roughly 6 p.m. until 8 a.m. the next day, walking back and forth along the length of the ship for hours, “wondering if he was okay or not.”

“I was still hopeful they were trapped or had found an air bubble,” she said.

After she found out Noe was gone, Hernandez recalled walking past a copy of Navy Times, and seeing her husband’s face among the fallen on the front page.

Her friends later told her she shook and pulled at the newspaper, but she doesn’t recall doing that.

“I remember thinking, that’s not my husband,” she said.

The community rallied around her, and Hernandez said she never went without in the following weeks and months.

“I never had to worry about whether my son was going to eat or not,” she said of a meal train organized by spouses from the carrier Ronald Reagan. “Water, ink for my printer, coffee, chocolate. It just appeared.”

While Japan was where her husband had died, Hernandez said it was hard to leave last fall and return to the U.S.

“I felt safe in Japan,” she said. “You would think I wouldn’t want to be there or leave, but I was very sheltered and protected.”

Still, life carried on, and Hernandez’s casualty assistance officer helped her make arrangements to move back home, without Noe.

”Nobody ever remembers him”

A year later, Hernandez said that figuring out who was responsible for the collision remains “a really hard topic.”

“This should never have happened,” she said. “They should never have put their training on the backburner and overworked our sailors the way they do.”

Big Navy has been accommodating, but like other families of the fallen, Hernandez said she wishes they could get all the answers to their questions.

“Everybody loved the hero, but when the hero dies, nobody ever remembers him,” she said. “The families remember. They paid the price.’

RELATED

Hernandez thinks more people should be held accountable and wonders why so many higher-ups escaped discipline.

“A lot of people were just pushed out and retired,” she said. “Where are the people that approved these things and knew the ship was not in a condition to go…people who made budget cuts and our sailors are working twice as hard and we are undermanned…why are they enjoying their retirement?”

She attended recent courts-martial and other legal hearings involving the Fitz sailors accused of causing the collision.

Hernandez said she’s not sure how she feels about those proceedings, or the accused.

“I do have a soft spot for some of the service members,” she said. “My husband was one of them. My husband could easily be in their shoes.”

“Everywhere you go is a memory”

Once she got back to Texas, Hernandez elected to live in town about 20 minutes from Weslaco.

The town they grew up in contained too much pain because Noe is everywhere.

“Everywhere you go is a memory,” Hernandez said. “This is where we met. This is the theater we went to. This is our high school. It’s both comforting and tormenting at the same time.”

RELATED

She’s going to school, studying psychology and social work.

One day, she would like to become a casualty assistance officer in the military.

Her focus is on their son, now 4-years-old, and preparing herself for the questions he will ask and the sadness he will feel when the enormity of the loss comes into focus over the years.

“I try to be very careful about the way I impact him, so I don’t harm him,” she said. “He’s going to deal with his grief all over again when he gets to a certain age.”

The boy remembers Noe, she said. He remembers the flag-draped coffin.

“When he sees a flag, he says, ‘papa,’” Hernandez said.

When he sees a flag and calls for his father, Hernandez tells him that he’s in heaven and loves them very much.

“I’m very grateful to have met my husband and have had 10 wonderful years with him,” Hernandez said. “I wish I had more time, but I’m lucky to have our son. That’s a part of him that no one can take from me.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.