ARLINGTON, Va. — For the first time in nearly four decades, Congress has radically reshaped the way officers can be recruited, trained and retained.

In next year’s $717 billion Pentagon spending bill, lawmakers inserted language that scraps key provisions of the landmark Defense Officer Personnel Management Act, 1980 legislation best known as DOPMA.

Signed into law on Aug. 13 by President Donald Trump, the National Defense Authorization Act lets the armed forces carve out alternate career paths for commissioned officers; modifies some “up or out” provisions to spare them from mandatory retirement; and dangles the promise of spot promotions for hard charging service members willing and able to quickly move ahead.

RELATED

The Navy is leading the charge, including mulling direct commissions for talented civilians with skills the service needs; softening the promotion zone to help officers hurdle their peers; and making it easier for reservists to seamlessly join the active force — and leave again for civilian jobs without penalizing their careers.

“We put together a vision for the officer management reform that would guide the officer communities of tomorrow,” Vice Adm. Bob Burke, the chief of naval personnel, told Navy Times. “We felt the existing framework had become a little over restrictive, so we weren’t advocating for throwing DOPMA away. We just wanted some additional flexibilities. I’m anxious to make use of all these new authorities right away.”

A champion of the reforms when he served as acting under secretary of defense for personnel and readiness between 2015 and 2016, Brad Carson is glad to see the Navy steaming ahead.

“All these reforms will slowly spread around the department, though some of the other services have been reluctant to use them, so far,” he said. "But I think once the Navy shows proof of concept you are going to see the other services more or less forced by the marketplace to adopt these.

“The Navy, to their great credit, is really thinking through these more than the other services are.”

That marketplace is so competitive because of two forces now shaping the 21st century military.

The Navy faces an increasingly fierce rivalry with the other armed forces and private industry for the nation’s best talent.

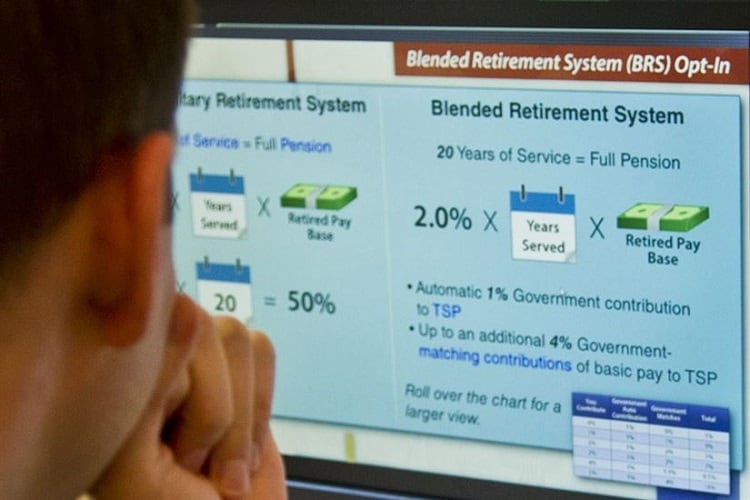

And within the military, the services are scrambling to adapt to the new Blended Retirement System, which is replacing the traditional pension program that guaranteed officers a pension after 20 years of service.

RELATED

“Now that the the 20-year retirement carrot is becoming a thing of the past, the Navy and the other services will need other ways to keep people if they are to retain both officers and enlisted beyond the 12-year mark because that fact alone exponentially changes the ability to predict human behavior as it is fundamentally changing the playing field," said retired Cmdr. William D. Hatch, a senior lecturer on manpower issues at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California.

To Hatch, Carson and other experts, the new post-DOPMA reforms put a premium on retaining good officers. Keeping them happy and willing to stay in uniform also cuts costs incurred by recruiting and training their replacements.

That’s why the Navy wants to soften the promotion zone so some top-performing officers can leapfrog their peers.

“Right now, when the Navy sets who gets promoted first, it’s based on the officer’s lineal number — which are determined on their commissioning day — their order of merit when they were ensigns,” Burke said. “Now, we’ll be allowed to take the top 15 percent of the officers, as ranked by the board, and pay them immediately for their new rank. Arguably, the most talented officers will get paid ahead of the others and the rest will spread over the fiscal year as is done today — it’s not extra money, but they get it quicker.”

The Naval Postgraduate School’s Hatch likes it.

“Things like this idea will be a great boost for officers, as in the past, it could take a year or 18 months for them to actually put on the rank and get paid for it,” Hatch said. “This could be a significant morale boost to the top performers and become a good incentive for retention.”

DOPMA strengthened the Cold War military’s “up or out” system by forcing officers to retire if they’re passed over multiple times for promotion.

It was a predictable way to manage large numbers of officers, but today’s military is significantly smaller than the armed forces that stared down the Soviet Union, and the Pentagon is searching for 21st century flexibility to manage an increasingly educated workforce.

That flexibility includes letting the Navy blaze alternative “up or stay” career trails. Lawmakers want mid-career officers passed over for promotion to be able to continue their jobs — so long as they’re competent and possess skills needed by the fleet.

To test that, the Navy will soon launch a pilot program that exempts flight instructors from mandatory “up or out” exits.

“Today, we have many mid-grade aviators who leave the service early at that post-department head level, right about when their minimum service requirement ends,” Burke said. “Many of these officers have told us they’d be happy to stay if they could remain on and just fly.”

Already competing with commercial airlines for aviators, the Navy has struggled with staffing operational squadrons. Pulling pilots for flight instructor duty exacerbates shortages.

The Navy’s solution is the Permanent Flight Instructor Program.

“If we can give officers who would otherwise leave and give them the opportunity to remain on as long-term flight instructors using these new authorities it would be a win for us,” he said.

That sort of nontraditional career track won’t affect most other aviators, much less submariners, SEALs and surface warfare officers, Burke said, but alternative career routes could send them down parallel pathways that would limit promotions, but keep them productive until they retire.

“The O-4s are where we’ll start, but we would have the authorities to take O-3s now and continue them even beyond 20 years or set up a separate promotion category, promote them and keep them beyond 20 years,” Burke said. “We have all sorts of flexibility here with these authorities.”

To Burke, the push to offer more optional career tracks builds on proven alternative professional paths already available to some sailors.

“Today, we have this thing called ‘specialty career paths’ — such as surface warfare officers who become ballistic missile defense specialists. We see those opportunities, especially as the Navy grows, moving into these alternate career paths,” said Burke.

The flight instructor experiment might become the model for deeper changes, which is why the Navy will announce the program next month and ask lieutenant commanders to volunteer for three-year stints.

“We’re still working the final planning, but I anticipate the first year we’ll do somewhere between 20 and 30 quotas, so we’ll start small to see how this works and we’ll see how many really stay on long-term,” Burke said. “Then if it’s working well, we’ll grow it, but we are planning that there will always be a balance, a mix of fleet returnees and the permanent instructors.”

To Burke, that also makes the traditional trail to command “cleaner” for those who want to move up and lead. And he has something special in the works for those go-getters, too: spot promotions.

Under DOPMA, the Navy had very few ways to help an officer already primed for higher rank hurdle peers in the sailor’s year group.

An exception was the surface warfare Navy’s ability to temporarily promote a lieutenant to lieutenant commander if the officer volunteered to become a chief engineer or an Aegis Combat Systems officer.

“These are highly technical jobs, high-demand and challenging department head jobs where these officers are hand-picked people who have the ability to succeed through those training tracks,” Burke said.

Once they report to their new jobs, surface warfare officers are nominated for a special spot promotion board and the U.S. Senate still must confirm their temporary ranks.

While they’re still at their new jobs or soon after they leave, they will go before lieutenant commander promotion boards alongside peers who didn’t take on the harder challenges to keep their temporary ranks.

Burke said that the DOPMA changes will now allow spot promotions to the ranks of commander and captain, but the secretary of the Navy must greenlight which career fields will get them.

The Navy is putting together a proposed list now.

RELATED

And if the Navy can’t fill some highly technical or unique specialties from within, they now can directly commission “push-button officers," captains and below.

Officials are targeting proven civilian leaders in high tech fields, especially software engineers.

That also breaks from traditional DOPMA controls on officer promotions. Under its “up or out” provisions, for example, no more than half of eligible commanders could be promoted to captain, usually after they accumulated more than two decades of commissioned service.

There were some exceptions that allowed the Navy to offer direct commissions to civilian professionals such as physicians and attorneys, but they were brought in at the lieutenant level, a rank Burke insists is too low to woo engineers away from Silicon Valley.

“We really need software engineering expertise — but do we need these people to be naval leaders? That’s the question we have to ask,” he said. “If the answer is ‘no,’ maybe we can make their pay more competitive by directly accessing them at a higher grade, equivalent of O-4, 5 or even O-6.”

To the armed forces, a long immersion in the military and years of leading troops are proven means to test officers for higher command.

Burke insists that no one expects directly commissioned tech gurus to command warships, but they likely can helm software-development teams.

That sort of flexibility could prove crucial during wartime, when services must expand rapidly.

During World War II, units like the Seabees were assembled from skilled construction workers who entered the Navy in senior pay grades. Instead of building runways for an island-hopping campaign, however, today’s officers might work in cyberspace.

“This brings that kind of authority that has been gone since DOPMA came into effect, should we need to use it,” Burke said. “Our plan now is to use it on the margins, but it’s there if needed in a larger sense.”

Over the past decade, the Navy has perfected shifting enlisted sailors between the active and reserve force, a process that often takes several days.

But it might take months to bring one of the 14,500 reserve officers into the full-time, active-duty Navy.

That’s why the Navy is seeking broader flexibility, not only to activate commissioned reservists but also to let active-duty officers become part-time sailors or even civilians who can return to the fleet later.

“We really needed that flexibility and an opportunity to be able to get off the treadmill, occasionally take care of life-work balance and then to get back on the treadmill later without penalty to your career,” Burke said. “Today, a line officer can’t take a little time out of their career unless they do it through the career intermission program; otherwise, they’re going to be penalized.”

To Burke, an officer should be allowed to “see if the grass really was a little greener on the other side and be able to come back in.”

“Let’s say a surface warfare officer who may be separated and became an expert in cyber and now we want to capitalize on those talents they’ve developed as a civilian and bring them in rapidly as a cyber warrior,” Burke said.

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.