The bombs allegedly sent by a passionate Trump supporter to prominent liberals last week are a reminder that American history is littered with violence, with both the left and right pursuing political ends with explosives.

I’m a scholar who has researched conflict and its aftermath. From labor and anarchist unrest in the late 1800s to right-wing terror this past week, bombs have served political agitators as a shocking and deadly – but ultimately ineffective – way to fight their enemies.

Alfred Nobel’s 1867 invention of dynamite provided a weapon to the United States at the same time millions of industrial workers were laying the foundations of U.S. prosperity in the country’s mines, steelworks and slaughterhouses and on the oilfields, railroads and piers.

The extraordinary wealth that their labor produced went to enrich the factory and business owners and the financiers, whose names still resonate today – John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and J.P. Morgan.

The disparity in rewards was clear to labor leaders, and as early as the 1880s they campaigned to improve working conditions and rates of pay for all. In the mix were radicals who believed in the “propaganda of the deed” – and that only through a major shock to the status quo could the system of exploitation be changed.

For these radicals — including Albert Parsons, editor of the anarchist publication The Alarm – dynamite was “a genuine boon for the disinherited.” When combined with mass-produced gas or water pipes, dynamite gave desperate men an easily concealed and transported means to disrupt the system they so resented.

They did so in Chicago in May 1886. During protests against police shootings, and in support of the eight-hour workday, someone threw a gas pipe bomb at police, “the first dynamite bomb ever used in peacetime history of the United States.”

The incident became known as “the Haymarket Affair” or “the Haymarket Riot.” Seven policemen and four demonstrators were killed.

Following the incident, newspapers carried detailed stories about the assembly and distribution of gas pipe bombs, especially the work of bombmaker Louis Lingg.

Lingg and Parsons were both tried and sentenced to death, even though neither threw the bomb that day. Six other men were also prosecuted following the Haymarket bombing. Lingg later committed suicide.

The gas pipe bomb in the 1880s was a weapon deployed by revolutionaries against powerful institutions of capital. Activists were willing to die for their beliefs, and used bombs in response to what they saw as everyday or “structural” violence, whereby states, governments and powerful companies pursued their own interests by exploiting ordinary people, and harnessed the instruments of “law and order” to shut down peaceful channels of dissent and change.

Bombs were again used in the famous Wall Street explosions on Sept. 16, 1920. At the financial heart of the country, near the banking giant J.P. Morgan and Co. building, 100 pounds of dynamite hidden in a horse-drawn cart detonated, sending shrapnel into the bodies of passersby and killing 38 people. Hundreds more were injured. It was the biggest terrorist incident in the United States until the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, and was never solved.

Pipe bombs were again wielded for political purposes in the United States in the polarized 1960s and 1970s. The Weather Underground saw themselves as heirs to the 1880s anarchist revolutionaries and believed violence was necessary to achieve social and political change.

Known as the “Weathermen,” they claimed credit for bombing the New York City police headquarters in 1970, the same year a bomb their members were assembling accidentally went off and killed three of them. In July of that year, they claimed credit for bombing a New York bank after 13 Weathermen were indicted for conspiracy to commit terrorism. By 1975, the group had claimed responsibility for more than 25 bombings.

This period also saw extremists using bombs not against power elites and their policies, but to intimidate or eliminate voices of progressive change.

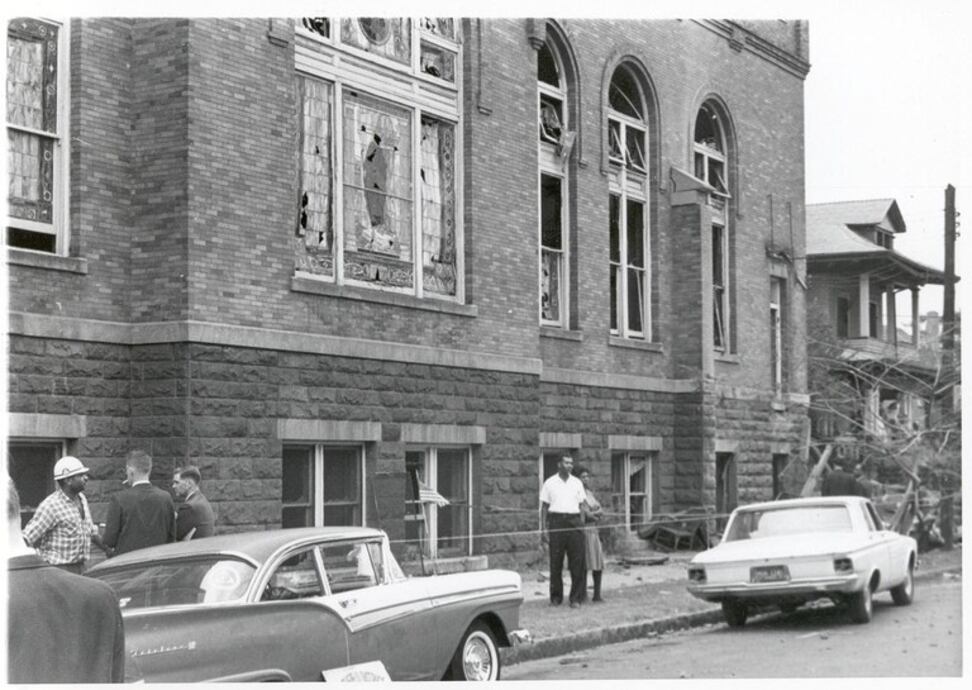

Dynamite was the weapon of choice by the four Ku Klux Klansmen who bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sept. 15, 1963, killing four African-American schoolgirls. Although no prosecutions were made until 1977, 2001 and 2002, this hate crime was a catalyst in driving public support for the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Less well-known are earlier pipe bomb attacks in California – two against liberal ministers who had criticized “radical right” groups in February 1962, and a third targeting the American Association for the United Nations in March 1963.

The February 1962 pipe bombs exploded as the Reverend Brooks Walker and the Reverend John Simmons were participating in a discussion panel hosted by a synagogue in Beverly Hills, with the title “Extreme Right – Threat to Democracy?”

The March 1963 pipe bomb exploded on the same night that the Rev. Brooks Walker was sworn in as President of the Association for the United Nations. The incident prompted Republican Sen. Thomas Kuchel to denounce the work of those he termed the “fright-peddlers” who encouraged such behavior.

No one was killed. But these bomb attacks, like the pipe bombs sent in early October 2018 to Democratic leaders, targeted individuals and their families who were vocal opponents of what they saw as the inflammatory, polarizing words and actions of extremists on the right.

Since the invention of dynamite, bombs have been a tool of choice for devotees of the entire range of fringe American political thought. Anarchists, radical left-wingers and racial supremacists, as politically different from each other as night and day, have been united in one thing: their use of a particular form of violence to achieve political ends.

They are united, too, in one other way: These methods haven’t worked.

Dr. Keith Brown’s research has focused primarily on politics, culture and identity in the Balkans, with a particular emphasis on relations between Macedonia, Greece, and Bulgaria. His solo-authored scholarly work has explored the comparative politics of history-writing (The Past in Question, 2003), and analyzed the nature of violence in the making and breaking of community (Loyal Unto Death, 2013). He has also pursued collaboration across scholarly and professional boundaries in research on civil and military forms of international intervention, especially in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Iraq. This has produced edited volumes focused on democracy promotion (Transacting Transition, 2006) and comparative approaches to post-conflict studies (Post-Conflict Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach, 2015; co-edited with Chip Gagnon). He is co-director of the NEH-funded Dialogues on the Experience of War project at Brown University, 2017-2019.