Early in World War II, less than three months after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese held the initiative throughout the Pacific.

The Dec. 7, 1941, attack had put the American battleships out of action but missed the carriers. The Japanese partially corrected this oversight a month later when a submarine torpedoed the aircraft carrier Saratoga, sending her back to the West Coast for repairs.

With its few remaining carriers, the Navy took the battle to the Japanese.

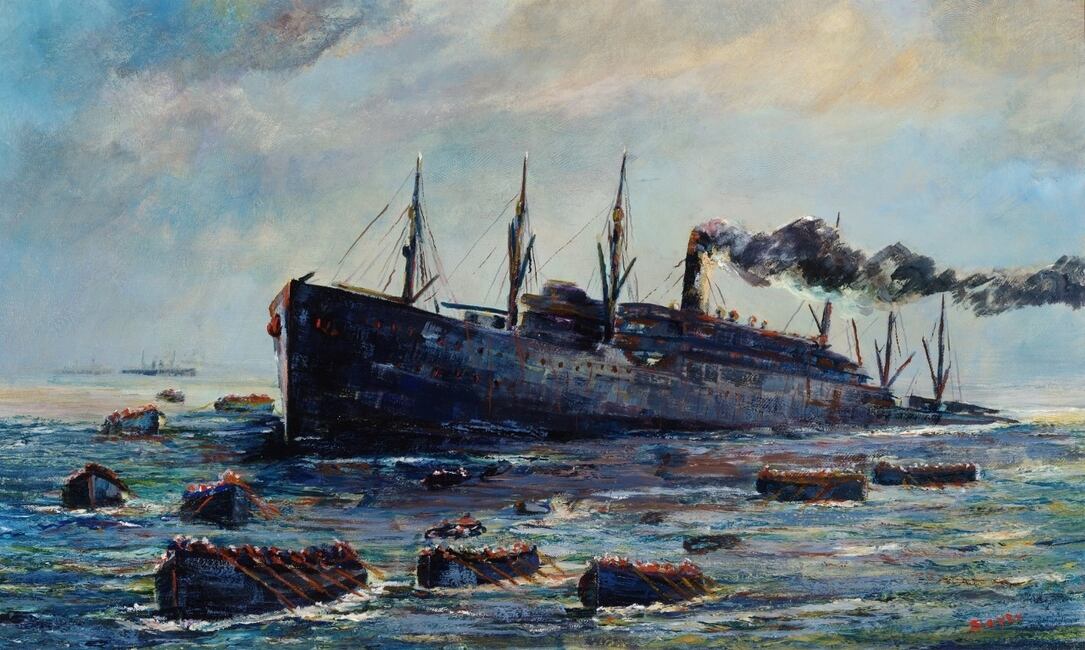

On Feb. 20, 1942, the flattop Lexington was steaming toward the Japanese base at Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, when it was approached by two enemy flying boats. Their crews managed to signal its coordinates before American fighters flamed the planes, and the Japanese immediately launched an attack against Lexington.

That chance encounter had dire implications for the U.S., which couldn’t afford the loss of a single ship and certainly not a carrier.

American radar picked up two waves of Japanese aircraft. Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bombers—good planes with experienced pilots.

Six American fighters led by legendary pilot Jimmy Thach intercepted one formation, breaking it up and downing most of the Bettys.

The second wave, however, approached from another direction almost unopposed.

Almost.

Two American fighters were close enough to intercept the second flight of eight bombers. The Navy pilots flew Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats, which like most American planes were practically obsolete at the time, certainly inferior to the best Japanese aircraft.

At this point in the war, the Navy had to rely on the men who flew them.

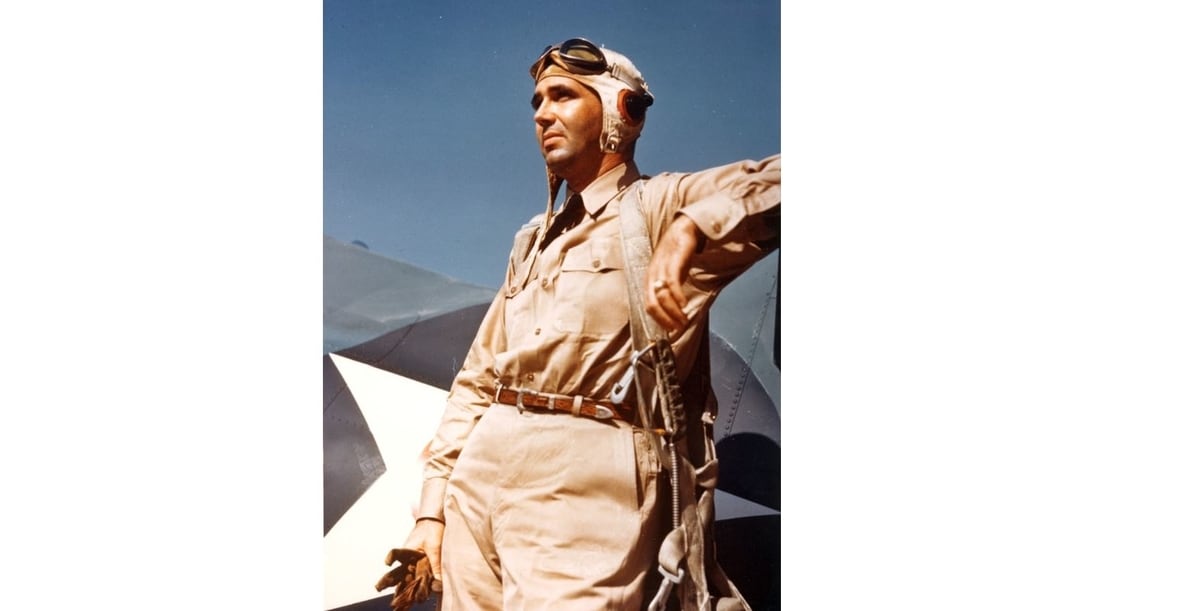

As the Japanese bombers dove from 15,000 feet, the guns jammed on one of the Wildcats, leaving Lexington’s fate in the hands of one young American aviator. Lt. Butch O’Hare —who’d been aboard Saratoga when she was torpedoed—had only enough .50- caliber ammunition for about 34 seconds of sustained firing.

And the Bettys were mounted with rear-facing 20mm cannons, a daunting defense.

O’Hare’s aircraft may have been inferior, but his gunnery was excellent.

Diving on the Japanese formation at an angle called for “deflection” shooting, but Thach had taught his men how to lead a target.

O’Hare flamed one Betty on his first pass, then came back in from the other side, picked out another and bored in.

Still too far away to help, Thach observed three flaming Japanese planes in the air at one time.

By the end of the action, O’Hare had downed five of the attacking Japanese planes and damaged a sixth, approaching close enough to Lexington that some of its gunners had fired on him.

After landing on the carrier, he approached one sailor and said, “Son, if you don’t stop shooting at me when I’ve got my wheels down, I’m going to report you to the gunnery officer.”

Thach estimated that O’Hare had used a mere 60 rounds for each plane he destroyed. It’s hard to say which was more extraordinary—his courage or his aim. Regardless, he had saved his ship.

On April 21, 1942, at a White House ceremony, Rita O’Hare draped the Medal of Honor around her husband’s neck as President Franklin Roosevelt looked on.

Roosevelt promoted the pilot to lieutenant commander.

Later in the war, Butch O’Hare was killed off Tarawa while flying a pioneering night intercept against attacking Japanese torpedo planes —an exceedingly dangerous mission, employing tactics that were in their infancy.

He had volunteered. Aviators throughout the fleet reacted with disbelief at the news that Butch O’Hare was dead.

RELATED

There is a surprising footnote to the story.

“O’Hare” resonates with Americans today for the airport in Chicago that bears his name.

Ironically, O’Hare’s father had been an associate of Al Capone. On Nov. 8, 1939, “Easy Eddie” O’Hare was gunned down a week before Capone was released from prison, supposedly for helping the government make its case against his former boss.

His son, Butch, was in flight training at the time, learning the skills he would put to use little more than two years later in the South Pacific.

This article was originally printed in the August 2008 issue of Military History, a sister publication to Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.