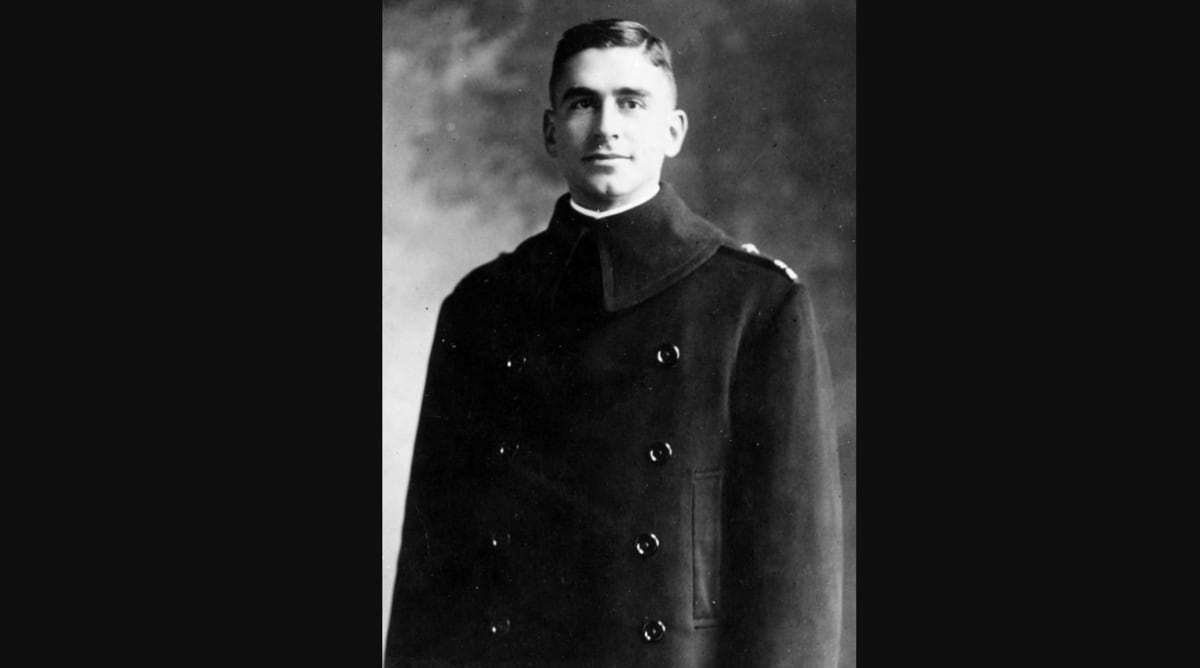

Edouard Izac was born in Iowa in 1891, but grew up speaking German at home. (His father hailed from the German-speaking area of Alsace, France, while his mother’s parents had emigrated from an area of Germany whose dialect was similar to that spoken in Alsace.)

Izac concealed his facility with the language from German captors when they held him aboard their U-boat in 1918. Had they known Izac understood all they were saying, they would have spoken less freely.

Izac graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1915 and initially served on the battleship Florida. When America entered World War I, he transferred to the Naval Transport and Supply Service.

In July 1917, the junior-grade lieutenant was assigned to the troopship President Lincoln, which had been a German Hamburg-America Line passenger steamer of the same name until seized by the U.S. government.

By spring 1918, Izac had made five transatlantic crossings from New York on President Lincoln, which transported some 23,000 troops to Europe. By that fifth voyage, Izac had become the ship’s executive officer.

In late May 1918, President Lincoln disembarked its latest load of troops at Brest, France, and on the 29th started for New York in a convoy escorted by destroyers.

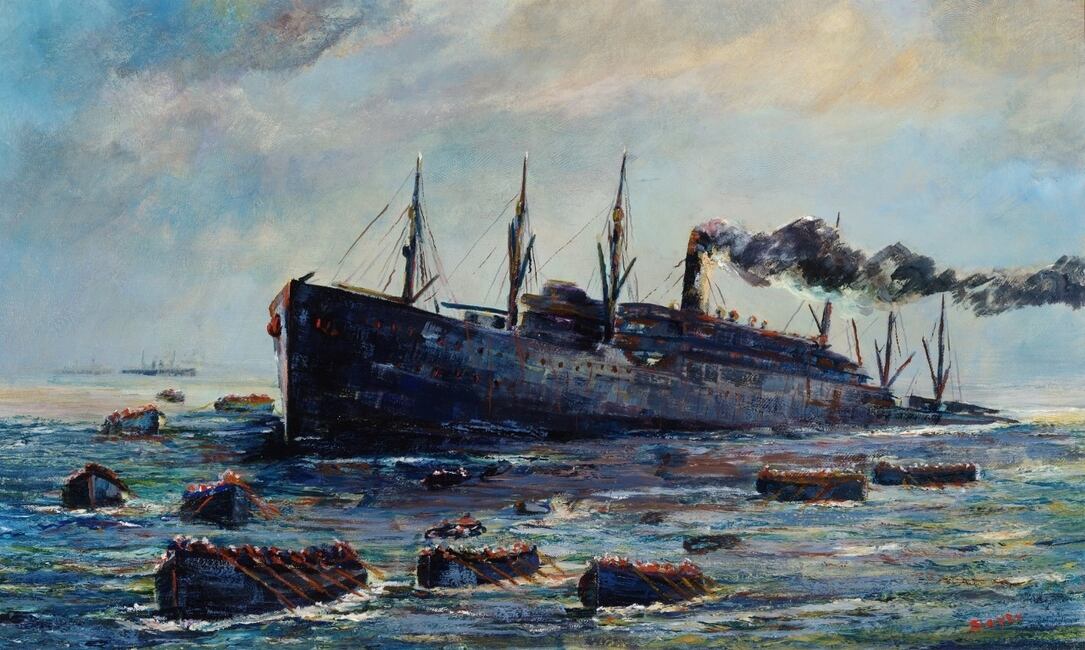

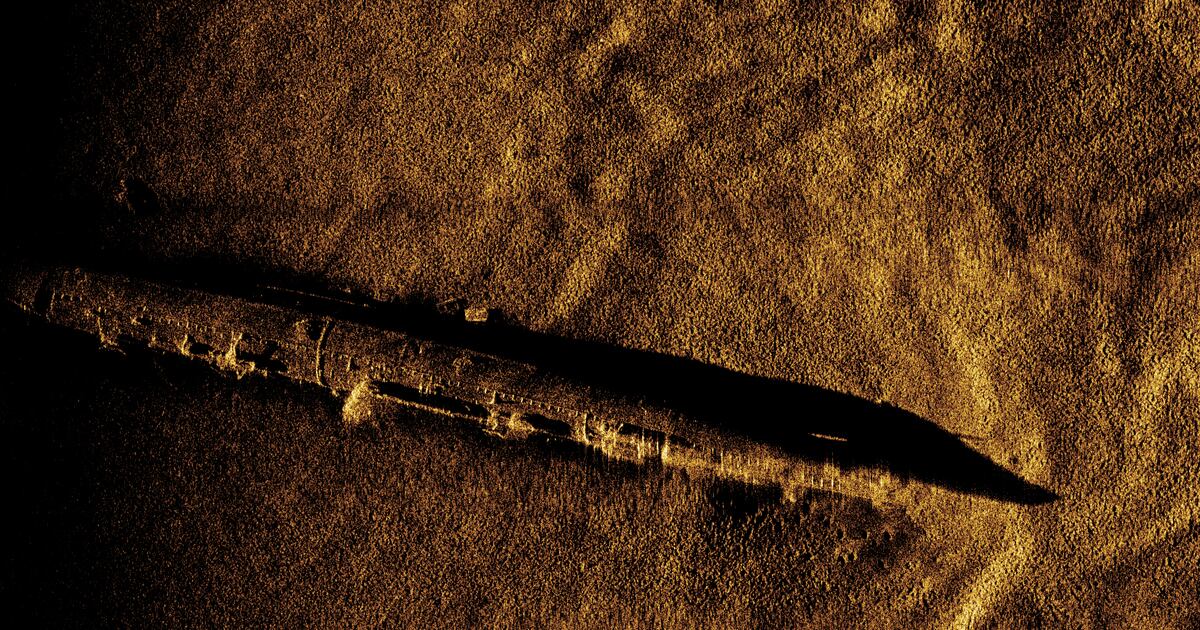

At sundown the following day, the escorts left the convoy as it passed beyond what was considered the U-boat danger zone. But just before 9 the next morning, the German submarine U-90 put three torpedoes into President Lincoln.

Although the transport sank in little more than half an hour, most of the 715 men aboard managed to get into the lifeboats.

U-90, meanwhile, surfaced, and its commander demanded the transport’s captain accompany the sub to Germany as proof of the sinking. Izac, speaking English, told the Germans the captain had been killed in the attack, so the U-boat crew took the executive officer prisoner instead.

While aboard U-90, Izac listened to and watched everything around him. Gaining critical intelligence that could be used against the U-boats, Izac knew he must get the information to Allied authorities.

Soon after arriving in Germany, Izac was placed in a POW camp, from which he made several escape attempts. A month later, guards put him on a train to another camp. En route he leaped from a window of the speeding train under fire.

Recaptured and severely beaten, Izac attempted escape again after reaching the new camp. After scaling the barbed wire one night, he purposely drew fire from guards, enabling other POWs to flee.

Izac and a fellow prisoner then made their way through Izac’s ancestral homeland, hiding in the woods and living on raw vegetables.

Reaching the Rhine, they evaded German sentries and swam across to Switzerland. Izac finally reported to the Bureau of Navigation in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 11, 1918, the day the war ended.

RELATED

The fact that Izac’s information was no longer useful detracted in no way from his heroism during more than five months as a POW. He received the Medal of Honor, but the injuries he sustained during his escape attempts ended his Navy career.

He was medically retired in 1921 as a lieutenant commander.

From 1937 to 1947, Izac served in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat from California. A member of the House Naval Affairs Committee, he joined a delegation of lawmakers that inspected the liberated Buchenwald, Mittelbau-Dora and Dachau concentration camps in April 1945.

Izac died in January 1990 at age 98.

The U.S. Navy’s first recipient of the Medal of Honor for heroism as a POW was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

This article was originally published in the May 2010 issue of Military History, a sister publication to Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.