Before construction was even complete on the Union ironclad Monitor, the vessel attracted a lot of attention.

Many enterprising young men clamored to sign up for service on board it, and in the end the ship, which had originally been dubbed Ericsson Battery, attracted many more volunteers than would be required for its first crew.

On March 6, 1862, Monitor left New York with a crew of 63, seven officers and 56 seamen. The men who served aboard the famous ship would develop a special bond with each other during the nine months they spent together, and they soon came to refer to themselves as “Monitor Boys.”

The young sailors were three-year volunteers who wanted to serve their country. They had heard about the Swedish inventor John Ericsson and his ironclad, and in signing up for service aboard Monitor they looked forward to exciting times aboard the Navy’s most modern warship.

Monitor‘s crew members came from various backgrounds. Many had been born in northern Europe, particularly Ireland and Scandinavia. This foreign recruitment by the Navy was due to the scarcity of native seamen. More and more inexperienced men, many of them immigrants, had to be enlisted, and at one time during the war foreign-born men constituted one-fourth of enlisted Union sailors.

Monitor was especially attractive to the Swedish because of her designer. On March 9, 1862, during the battle at Hampton Roads, the vessel’s crew included three Swedes: Mark T. Sunstrom, third assistant engineer, and Seamen Hans Anderson and Charles Peterson, who were stationed in the gun turret.

Another member of the ironclad’s crew had arrived from Bombay. Tired of being a landlubber, he decided to volunteer for Ericsson’s Monitor “about which something had been whispered among the men.” After having seen her, he provided the following description:

She was a little bit the strangest craft I had ever seen, nothing but a few inches of deck above the water line, her big round tower in the center, and the pilothouse at the end….We had confidence in her though, from the start, for the little ship looked somehow like she meant business, and it didn’t take us long to learn the ropes.

In addition to enlisted crew, top officers often hired black men as private servants. Because they had been Confederate “property,” and therefore were liable to confiscation, they were termed “contraband of war.”

Since September 1861 the secretary of the Navy had ruled that escaped slaves could be enlisted, but at "no higher rating than ‘boys.'”

They were treated as second-class sailors, but nonetheless were much appreciated. Most of the black crewmen served as cooks or stewards. On board Monitor was black servant Thomas Carroll, who became very popular.

When Acting Asst. Paymaster William Keeler was looking for a manservant to tend to his needs, he wrote, “I have spent a portion of two or three days in hunting up a contraband & finally found a good looking young (man) that came to me well recommended.”

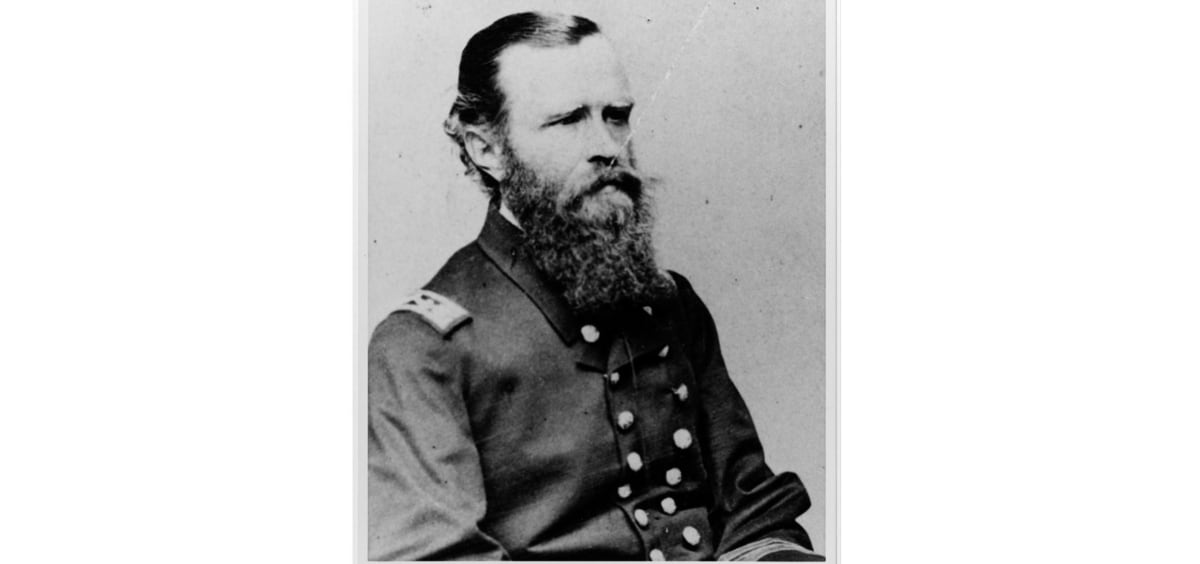

Lt. John Lorimer Worden was proud of his crew, declaring, “A better one no naval commander ever had the honor to command.”

Before sailing, he fully explained the dangers of a sea passage, with the absolute certainty of a battle to follow.

All the accommodations on Monitor lay below the water line on the berth deck. The living quarters were in front of the bulkhead that divided the vessel in two halves, with engine and boiler rooms aft.

As a custom from the age of sail, officers almost never associated with sailors, for they considered “the men” as belonging to a lower class. It was an insult to refer to an officer as a “sailor.”

As a result, officers had access to better food, uniforms and quarters than enlisted men. The seven commissioned officers enjoyed private cabins and a handsomely fitted wardroom near the bow. The crew, however, had to hang their hammocks in a common room behind the wardroom with storage lockers on the side.

Life belowdecks enclosed the crew in an artificial environment. Ericsson had tried to make it as bearable as possible and designed the interior with skill. There were no windows on the nicely decorated iron walls, but skylights of thick glass in iron frames above enabled light to enter during the day.

Rough seas washed the skylights with water, and during action the crew covered them with iron plates. Monitor included a ventilation system, powered by a “donkey” engine that supplied fresh air through openings in the floor to cabins and boilers.

Despite Ericsson’s intricate constructions, one crew member recalled that “no ship was ever devised which was so uncomfortable for her crew” and termed Monitor “the worst craft for a man to live aboard that ever floated upon water.”

When Monitor was scheduled to leave Brooklyn, a severe storm prevented its departure. Waiting out the weather, the officer of the watch penned in the log, "John Aitkins deserted and took with him the ship’s cat and left for parts unknown."

The boy probably was frightened by the enclosed atmosphere belowdecks, and never came back with the pet.

The iron ship magnified surrounding temperatures, making it hotter than it was outside during daylight and cooler at night. During the summer months the crew suffered from the heat. Once when a blower belt broke the temperature reportedly rose to 132 degrees on the berth deck. Members of the crew therefore slept on deck as much as possible while the vessel was in the James River, although that was not always possible, due to enemy fire.

Keeler recalled, “We lay broiling in our iron box, or cage as it has now become, out of humor with ourselves & the world generally.”

In winter the ocean chilled the air, although steam heaters had been installed in the wardroom. Of course, the crews of the Confederate ironclads also suffered enormously from heat, cold and sickness. Their accommodations were located on the berth deck among the guns, and their ships lacked Ericsson’s ventilation and heating system.

Because waste could not be gotten rid of by gravity, Ericsson designed an intricate “rubbish-gun” for dealing with excrement.

On Monitor‘s first voyage, Dr. Daniel Logue, the ship’s surgeon, had a vague idea that “the guns” involved the activation of levers for evacuation into the sea. Unfortunately, he omitted an essential part of the procedure and “found himself suddenly at the end of a column of water rushing up from the depth of the ocean and pouring into the ship.”

When Dr. Logue was found lying in a big pool of water, engineer Isaac Newton had to be called to close the lower port of the tube. After that event, he lectured the crew on how to properly operate the “gun.”

The only recreation available occurred on deck, when the weather allowed. One photo shows members of Monitor‘s crew outside on deck covered in smoke near a stove with pots and pans. The sailors were preparing a meal next to the turret.

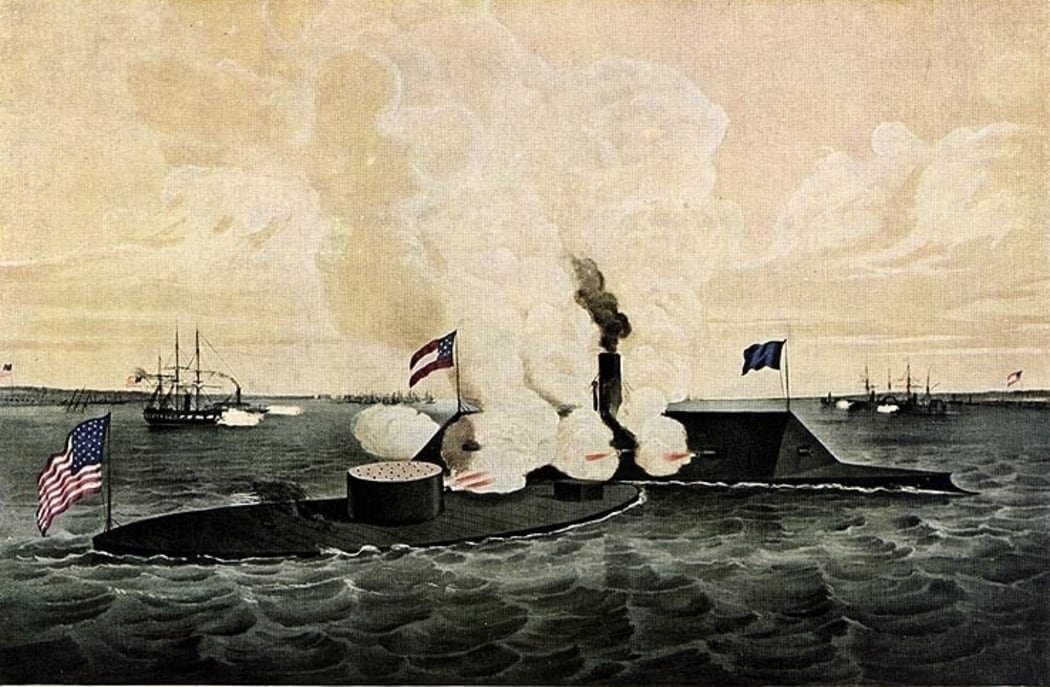

During the March 9 Battle of Hampton Roads, Monitor dueled with the Confederate ironclad Virginia, which had been stalking the Union steam frigate Minnesota.

The two vessels pounded each other for two hours, after which Capt. Worden decided to replenish Monitor‘s ammunition before returning to battle. Worden himself was wounded shortly thereafter when a Confederate shell struck one of the ironclad’s viewing slits. At that juncture, the Federal vessel broke off contact.

Author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who visited Monitor after the Battle of Hampton Roads, was frightened by what he saw and called it “the strangest-looking craft I ever saw, a giant rat-trap.” He continued, “There is no remoteness of life and thought, hermetically sealed seclusion, except, possibly, that of the grave, into which the disturbing influences of war do not penetrate.”

Following the engagement with Virginia, the crew was able to take it easy for a while. After the battle, Northern military leaders decided that they did not want to expose their precious ironclad to Confederate shells for a time.

The Monitor Boys, however, were eager to proceed to Norfolk, where they hoped to win a final and decisive victory. For some time, however, there was no opportunity to show off Monitor‘s fighting ability. Life on board soon settled into a monotonous routine. Keeler expressed the crew’s frustration, writing, “I believe the Department is going to build a big case to put us in for fear of harm coming to us.”

Another source of frustration was the frequent change of command after Worden was wounded at Hampton Roads. During 10 months’ service Monitor had no fewer than five different commanders. Immediately after Worden’s wounding, Lt. Samuel Dana Greene took command. He hoped to continue in that position. In a letter to his mother, he proudly wrote:

The fight was over, & we were victorious. My men & myself were black with smoke and powder. All my underclothes were perfectly black with smoke, and my person in the same condition….I felt proud and happy then, Mother, and felt fully repaid for all I had suffered….I was Captn. & first lieut. and had not a soul to help me.

Replaced shortly after the battle, Greene was saddened and disappointed. But he was only 22 years old, and before coming to Monitor he had never served in a higher position than midshipman. After the battle he was criticized for not continuing the fight with Virginia. He faithfully stayed on, however, until the end, when Monitor foundered off Cape Hatteras.

On April 24, 1862, while Monitor was positioned near Fort Monroe, the ship’s crew sent a letter to Lt. Worden, who was then still recovering from his wounds:

To our Dear and Honored Captain. These few lines is from your own Crew of the Monitor with their Kindest Love to there Honored Captain, Hoping to God that they will have the pleasure of Welcoming you Back to us Soon, for we are all ready able and willing to meet Death or anything else, only give us back our captain again. Since you left us we have had no pleasure on Board of the Monitor. We remain until Death your Affectionate Crew,

The Monitor Boys

After the historic battle at Hampton Roads, Monitor and her crew became the center of attraction for visitors of all kinds, from President Abraham Lincoln, congressmen and newspaper reporters to family members and friends. When the vessel was moored in Hampton Roads, in the James River or at Fort Monroe people made every effort to see the “monster.”

The president came twice, in May and July of 1862, and had much praise for the ship and the Monitor Boys.

In July photographer James Gibson arrived from New York to take stereographic pictures of the ironclad and her crew. Gibson was part of a team employed by Mathew Brady, who orchestrated a series of famous photographs of the Civil War. Some pictures capture the crew and officers lined up before the turret, and others show the effects of the projectiles that hit the iron plating.

On May 15, 1862, Monitor took part in the First Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, but was unable to elevate its guns enough to reach the Confederate positions, and the Union effort to advance up the James River to Richmond ended in failure.

After that, the summer months settled into a monotonous routine that started each day at 5:30 a.m., when petty officers roused the crew from their hammocks. The ship was swept, bright metalwork polished and clothes scrubbed. Later on the sailors were kept busy standing watch and drilling at the cannons, while the firemen served the engines.

The happiest day for the Monitor Boys came on September 30, 1862, when the ship was ordered up the Potomac to the Washington Navy Yard for extensive repairs. Furloughs were granted to many men, and the remaining crew members enjoyed a change of routine — better food and female visitors.

On November 5, a notice in the newspapers stated that the public was allowed to enter the Navy Yard to visit the ship. Carriages lined the wharves, and the vessel’s deck was jammed with people for hours. Keeler wrote: “They rushed in by thousands. Our decks were covered and our wardroom filled with ladies[,] and on going into my stateroom I found a party of the ‘dear delightful creatures’ making their toilet before my glass, using combs and brushes.”

The crewmen were understandably distracted by the women visitors. One man wrote: “We couldn’t go to any part of the vessel without coming in contact with petticoats. There appeared to be a general turn-out of the sex in the city, there were women and an extensive display of lower extremities was made going up and down our steep ladders.”

As the day ended, the men discovered that the visitors had taken souvenirs.

“When we came up to clean that night,” wrote one man, "there was not a key, doorknob, escutcheon — there wasn’t a thing that hadn’t been carried away."

The recently published letters by Monitor‘s 25-year-old 1st class fireman, George S. Geer, are moving documents of life on board Monitor. Geer enlisted from New York City, less out of interest in saving the Union than in earning money for his family. But he soon became an ambitious crew member. In November 1862, he wrote his wife, Martha:

Dear Wife

You should feel very proud to think your Husband is not a Coward at home, but is fighting for a country for his Wife and Children. And at the same time be thankful that I am not in some of these old Wooden tubs.

They are fixing the Monitor up much bettor than she was before. They will make a perfect little Pallace of her. The workmen work nights and Sundays. I can hear them hammering away as I am writing. They have named her Guns Worden and Ericsson, and have the names engraved on them in very large lettors, and also have engraved every shot mark where it come from, so People do not have to ask so many Questions…’

Your loving George.

Before departing from Fort Monroe on their final voyage south, the Monitor Boys enjoyed a Christmas celebration. Together they feasted on turkey, fish, oysters, a selection of meats, apples, figs, plums, jellies and wines — much of which had been sent from the men’s homes.

When they left port, they had high expectations for new adventures. Those expectations soon ended in tragedy. Shortly after midnight on December 31, 1862, Monitor sank in a gale off Cape Hatteras.

Sixteen crew members were lost.

The 49 survivors returned to Fort Monroe on the steamer Rhode Island. They would not forget their service on the famous little “cheese box on a raft.’”

Monitor was gone, but its crewmen were proud to have served aboard the famous vessel, and continued calling themselves the Monitor Boys. George Geer broke the sad news to his family:

I am sorry to write you we have lost the Monitor, and what is worse we had 16 poor fellows drownded. I can tell you I thank God my life is spaired.

You must not think because we have lost the Monitor that Vessels like her cannot be built to stand, as the Pasaic was in the same gale and stood it furst rate. You need not worry for me, as I am always looking out for No. 1 and I am not going to get killed or Drowned in this War.

Surgeon Grenville Weeks summed up Monitor‘s loss this way:

Our little vessel was lost, and we, in months gone by, had learned to love her, felt a strange pang go through us as we remembered that never more might we tread her deck, or gather in her little cabin at evening. The little “cheesebox on a raft” has made herself a name which will not soon be forgotten by the American people.

The Union’s ill-fated iron ship has not been forgotten in the ensuing decades, thanks to the efforts of schoolteachers, Civil War buffs and naval historians — as well as National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists, who orchestrated the raising of Monitor‘s gun turret from the waters off Cape Hatteras in 2002 and are working to preserve it at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

The ironclad’s crew would no doubt approve of the renewed publicity accorded their beloved ship so many years after its fabled battle at Hampton Roads.