From his Hellcat over coastal Honshū — the main Japanese home island — U.S. Navy Lt. j.g. Henry J. O’Meara marveled to see a Tokyo Plain “so thickly studded with airfields that 10 or a dozen were visible from almost any point.”

O’Meara, 21, had experienced combat, but many of his fellow aviators in the aircraft carrier Yorktown’s Fighter Squadron 88 were getting not only their first glimpse of Japan’s heartland, but a first exposure to aerial warfare.

After plastering enemy fields with tons of fragmentation bombs on July 10, 1945, O’Meara and mates were brimming with swagger. However, O’Meara wrote afterward, the fliers also were “quite disappointed over the lack of Jap planes in the air.”

The war was clearly in its closing days — or was it?

For months the Army Air Forces had dispatched B-29s carrying incendiaries over Honshū industrial centers like Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka to ignite firestorms.

And with the Okinawa campaign finally over, Pacific Fleet commander Chester W. Nimitz at last unleashed 3rd Fleet commander William F. “Bull” Halsey to pound Japan from its home waters with aerial attacks, shipping sweeps, and even shore bombardment.

But imperial militarists had not laid down their swords. Allied calls for unconditional surrender motivated the Japanese to fight even harder.

Invading the home islands would cost dearly. Japanese warlords had concealed several thousand planes for use in kamikaze attacks, hoping to destroy 30 to 50 percent of the invasion fleet before the Allies could land.

Third Fleet’s objective was to apply relentless violence in hopes that Japan would stand down — but, if not, lay destructive groundwork for an invasion.

Most seasoned American veterans longed for peace and home shores, but many untested men — especially hotshot aviators like those of VF-88 — were eager to square off with a foe, even one bent on a final showdown.

On July 1, Task Force 38, commanded by Vice Adm. John S. “Slew” McCain, had sortied from the Philippines, zigzagging at 17 knots toward Honshū’s Pacific coast, roughly 1,800 miles northeast.

McCain and Halsey still were feeling the lash of a court of inquiry that had assigned the two “primary responsibility” for fleet damage arising from a June 5, 1945, typhoon. Twice in less than a year inquiry findings had faulted Halsey for putting his forces in the track of murderous storms.

U.S. Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal wanted to retire the Bull but backed off; removing so popular a leader might boost enemy morale and prolong the war.

As historian Samuel Eliot Morison later put it, Bull and Slew now had “blood in the eye” and a force to express that wrath.

Three task groups, each consisting of two or three large Essex-class carriers and two light carriers, with battleship, cruiser, and destroyer screens, dominated the horizon.

Army Air Forces B-29s and U.S. Navy B-24s reconnoitered targets. Other land-based aircraft thwarted Japanese reconnaissance.

And U.S. Navy submarines ensured the task force made its approach undetected, or at least unmolested.

The power and personnel on the decks and in the ready rooms of the three task groups embodied years of planning, design, production, testing, recruiting, training, deployment, and combat experience.

Once, Japan’s airmen had staggered U.S. Navy aviators. Now the Americans all but owned the Pacific sky.

Through the war, the navy’s aviation training command had delivered rookies — “nuggets,” in aviator parlance — to staff squadrons. A nugget was likeliest to survive and thrive if he stuck with and learned from his flight leader.

Of the 14 air groups in Task Force 38, eight — including Air Group 88 — were making their first combat deployment and were dense with nuggets. VF-88, Air Group 88’s Hellcat fighter component, had formed at Atlantic City, New Jersey, less than a year ago and had joined Yorktown only two weeks earlier.

VF-88’s “Gamecocks” reported to Lt. Cmdr. Richard “Dick” Crommelin.

The Alabaman was one of five Annapolis-schooled brothers who served in the Pacific, four as aviators. Crommelin, 28, had flown with VF-42 off the first Yorktown.

During the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea, Crommelin, then a lieutenant (junior grade) jockeying a Wildcat, had helped destroy a Japanese flying boat and downed two Mitsubishi Zeros before being splashed himself.

At Midway that June, Crommelin helped defend the doomed Yorktown.

Twice awarded the Navy Cross and credited with 3.5 aerial kills, he had precisely the credentials to lead a fighter squadron.

His executive officer, Lt. Malcolm W. “Chris” Cagle, was another matter. The 1941 Annapolis graduate had served two years on “tin cans,” as sailors called destroyers, before undergoing flight training, then became an assistant flight instructor, and only now was facing combat.

VF-88, however, could count on half a dozen transfers with extensive fighting experience.

Lt. Howard M. “Howdy” Harrison of Columbus, Ohio, for example, had seen action over Makin, Eniwetok, Truk, Palau, and Hollandia. According to S. P. Walker, a press officer on Task Group Commander Arthur Radford’s staff, Harrison was “easily the most popular man in the squadron.”

Eight others qualified as “much pilots,” in airman argot, because they flew radar-equipped F6F-5N Hellcats like Henry O’Meara’s. In thick weather, these aviators often guided radarless Corsairs and Hellcats.

Like O’Meara, most in this elite cadre could claim at least some combat experience; two exceptions were the neophyte Lieutenants (junior grade) Ted Hansen of Santa Cruz, California, and Bill Watkinson of Montclair, New Jersey.

Two squadron stalwarts had distinctive personalities. Lt. j.g. Maurice “Maury” Proctor “was alert, quick off the mark, and apparently unafraid of anything or anybody,” wrote press officer Walker.

And Lt. j.g. Joseph G. “Joe” Sahloff, from near Albany, New York, thought to handle a Hellcat as well as any naval aviator, stood out for his gangling physique — as Walker put it, “in flight gear he looked rather like an aeronautical Ichabod Crane” — and for chain-smoking fat cigars, even aloft.

More typical of VF-88’s younger set were Ensigns John Haag of Lewiston, Pennsylvania, and Herb “Woody” Wood of Tipperary, Iowa — capable aviators in need of seasoning.

Wood, 22, already had a wife and baby; for luck, he had sewn one of his daughter’s booties to his leather flight helmet.

Back in February, as Intrepid, the carrier ferrying VF-88 to Hawaii, was departing San Francisco, a squadron mate had awakened him.

“Hey Woody! Get up!” the man shouted. “We’re going under the Golden Gate!”

Wood burrowed into his rack.

“No,” he said. “I’ll see it when I get back.”

Two other VF-88 youngsters required especially close mentoring: Ensigns Wright C. Hobbs of Indiana, nicknamed “Hybrid” for his fascination with strains of corn, and Eugene Mandenberg, in prewar days a reporter in Detroit.

Neither, many squadron mates thought, displayed fighter pilot demeanor or discipline. Woody Wood felt both were “too excitable.”

Bill Watkinson knew Mandenberg well, although he had not flown with him, and liked him. But, as Watkinson recalled, “he had a reputation of being more interested in the ‘flora and fauna’ than flying formation.”

As a Japanese aircraft carrier armada had when nearing Hawaii in early December 1941, Task Force 38 used a weather front to mask its July 9, 1945, approach to Honshū.

At 2 a.m. the next morning, the three task groups emerged, launched planes, and slipped back into the front to avoid counterattack.

Weeks of elaborate planning paid handsome dividends. Virtually unopposed — even flak was meager — American pilots pummeled 12 Tokyo-area fields, destroying some 109 ground-bound planes and damaging 231.

Out to sea, only two Japanese aircraft probed the task force.

Combat air patrols took out both. Flak did hit Lt. j.g. Ray Gonzalez’s Hellcat, but Gonzalez ditched safely near a rescue destroyer.

Refueling and replenishment ate up two days. When weather canceled sorties set for July 13 against northern Honshū and Hokkaido, the large island to its north, Task Force 38 retired east out of range.

The ships returned the next day, July 14, to conditions scarcely better but sufficient to sustain two days of flights against coastal targets as well as a foray by cruisers and destroyers to shell targets ashore.

For aviators, risk rose in tandem with foul weather.

Flying by instruments toward a target that day, Joe Sahloff’s Hellcat grazed Dick Crommelin’s. Crommelin disappeared, never to be found; a shaken Sahloff completed the mission.

Executive Officer Chris Cagle took command of VF-88 on the eve of yet another loss: Lt. j.g. Herman “Pancho” Chase, downed near southern Hokkaido’s Otaru Harbor and listed as missing in action.

During refueling on July 16, a second group centered on the British carrier Indefatigable — Task Force 37 — joined Halsey’s fleet.

July 18 strikes saw Yorktown lose two aviators, one of them VF-88’s Lt. j.g. Theron Gleason, claimed by flak.

The “Fighting Lady” retired east with Task Force 38 for four days to refuel, rearm and replenish — and let aviators rest.

“I am mixed up on the [dates],” Wood wrote in his diary. “I was so tired I never got to write.”

VF-88’s new commander was putting his stamp on the unit.

During squadron meetings, Bill Watkinson recalled, Cagle “invited” suggestions from veterans — but his body language made clear he wanted none.

“He was a bull, no questions asked,” said Watkinson, who had revered Crommelin but held Cagle in low regard.

After a July 24 strike, Watkinson remembered, Cagle led wingman Lt. j.g. Ken Nyer to the wrong rendezvous point, embroiling them in an overmatched fight with more than a dozen Japanese aircraft.

In the ensuing melee, Cagle shot down two Mitsubishi “Jack” fighters and got away, but Nyer went missing.

In scarcely two weeks VF-88 had lost its veteran skipper and three other aviators.

July 25 dawned soupy, limiting flights to airfield sweeps.

Enemy flak forced Howdy Harrison to ditch in the Japanese-controlled Inland Sea that separates Kyūshū — the southernmost home island — and Honshū.

Maury Proctor and Joe Sahloff saw their fellow airman escape to his emergency raft. Back on the Yorktown, they pressed to guide a Mariner rescue flying boat, known as a “Dumbo,” to where Harrison was bobbing.

That would keep the task force within range of Japanese counterattack, but the two got approval from the task group commander’s chief of staff.

The three planes plowed through overcast with a radar-equipped craft from another carrier initially bird-dogging the way.

“I could hardly make out Dumbo,” Sahloff said. “Often I couldn’t see Proctor at all.”

In the ponderous Mariner, pilot Lt .j.g. George B. Smith, low on fuel, could not climb above the murk.

A Japanese destroyer escort threatened Harrison until carrier pilots’ rockets and machine-gun rounds drove it off.

“I could hear the A.A. and see the smoke,” Harrison said. “Then it got quiet again.”

Finally the rescue triad — “a big St. Bernard…with a couple toy bulldogs,” as Proctor put it — broke through to clear sky pocked by puffs of enemy flak from a coastal airfield.

Smith set down on the swells for a double rescue: his crew heaved a lifeline to Harrison and towed the Hellcat pilot’s raft astern while cruising on to fetch Ensign John H. Moore, a Corsair pilot from the carrier Shangri-La who had ditched nearby.

After 45 anxious minutes, with both Harrison and Moore finally aboard, the Mariner lumbered aloft, droned to Task Group 38.4, and set down, fuel tanks all but dry.

Smith, his 10-man crew, and their charges were hustled aboard the destroyer Wren.

As the task group sailed east, 40mm gun crews aboard Wren and a second destroyer, the USS Mertz, scuttled the abandoned rescue bird.

On July 31, a typhoon threatened Task Force 38.

A cautious Halsey called off strike operations and instead had ships refuel while crews waited out the storm.

Under orders from Admiral Nimitz, Bull also dialed down his appetite for Tokyo targets. The air force boys had unspecified but major plans, so he put the force on a northerly course to hit northern Honshū and Hokkaido.

News of the A-blasts at Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and Nagasaki on Aug. 9 animated speculation.

An airman who had taken a physics course tried to explain atomic energy, but his lecture didn’t sink in, Watkinson recalled.

The evening of Aug. 10, according to the Yorktown after-action narrative, “all hands were electrified when a radio broadcast reported that the Japanese government had announced its willingness to consider the terms of the [Allies’] Potsdam ultimatum,” provided Emperor Hirohito could keep his throne.

Wrote Woody Wood: “We really thought the war was over for us today.”

But, if anything, action over Japan grew fiercer.

On a strike the day Nagasaki was hit, Wood “saw more A.A. than ever before” and VF-88 lost Lt. j.g. William B. “Dad” Tuohimaa.

That same day, while pathfinding for Corsairs, Bill Watkinson took a hit to his Hellcat’s port wing that left a rip as big as a manhole.

He limped to Yorktown, circled as other recoveries played out — staying aloft more than six hours —and made a jolting pinpoint landing.

Enemy pilots now seemed determined to fight.

On Aug. 8, the four aviators in Wood’s combat air patrol downed two would-be kamikazes.

“One plane burned right in front of me, the other spinning in at 16,000 [feet] and crashed in the sea,” he wrote.

On Aug. 9, airmen saw no enemy planes over targets but at sea combat air patrols splashed 12 Japanese aircraft.

Bad weather ruled Aug.11 and 12, with strikes canceled in favor of refueling.

On Aug. 13 aviators destroyed more than 400 enemy planes parked near Tokyo; combat air patrols downed 19 at sea — a “red letter day” for killing enemy aircraft, Halsey declared.

But it was also the day VF-88’s Lt. Wilson Dozier crashed in flames after losing a wing.

With peace near enough to touch, such losses were especially bitter.

After refueling on Aug. 14, Task Force 38 poised for two Aug. 15 scenarios: an end to hostilities, or another pummeling of Tokyo.

At 4:15 a.m., carriers launched combat air patrols and assembled aircraft for strikes and sweeps.

Two hours later, with planes in the first waves approaching targets, Nimitz ordered Halsey to suspend offensive operations: Hirohito had promised to surrender.

McCain immediately recalled planes aloft and canceled impending strikes.

Pilots able to do so jettisoned their payloads at sea and turned back. However, others, both Yanks and Brits, were already over Japan — and fighting to stay alive.

Four Hellcats returning to Hancock may have been the first Americans attacked in this white-knuckle countdown to peace.

Jumped by seven Japanese, leader Lieutenant Paul Herschel and mates downed a Zero and two Jacks, taking no losses.

At 5:45 a.m., Zeros jumped Indefatigable Grumman Avenger bombers escorted by eight Supermarine Seafires —naval versions of the Spitfire fighter — near a chemical plant near southern Honshū’s Odaki Bay.

Sub-Lieutenant Fred Hockley, flight leader for five of the Seafires providing close cover, went down in the first enemy pass.

Meanwhile, three top-cover Seafires, led by Sub-Lieutenant Victor Lowden, confronted a second Zero element.

Lowden, Sub-Lieutenant “Taffy” Williams, and Sub-Lieutenant Spud Murphy combined to splash six attackers and damage two more.

Sub-Lieutenants Don Duncan and Randy Kay, two of the now-leaderless close cover pilots, rallied to down a pair of Zeros, too.

The Avenger crews held course, fended off other Zeros, dropped bombs, and flew back.

All bombers save one landed on Indefatigable; the other ditched near a friendly destroyer.

The seven surviving Seafire aviators, concerned foremost with Hockley’s fate, only learned of the cease-fire upon touching down. (Hockley had bailed out, but the Japanese quickly captured him and that night executed him in secret.)

Shortly after the British-Japanese air battle, 23 Hellcats and Corsairs from Yorktown, Shangri-La, and Wasp were approaching Chōshi, the Tokyo area’s easternmost city.

The eight VF-88 Hellcats were to split into two groups at Tokurozama airfield, northwest of Tokyo. Two pilots would stay high to receive and relay any cease-fire message while the rest — Howdy Harrison, along with Maury Proctor, Ted Hansen, Joe Sahloff, Wright Hobbs, and Gene Mandenberg — attacked.

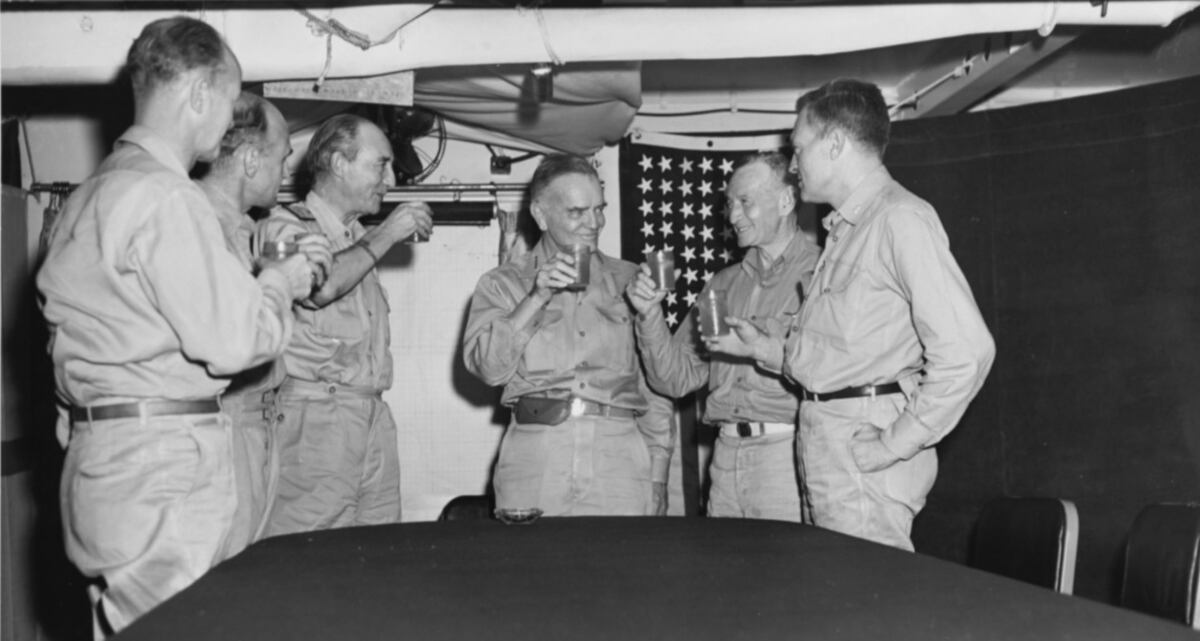

VF-88 pilot and diarist Herb “Woody” Wood with his plane at Hawaii, months before he and his fellow airmen tangled with Japanese fighters over Honshu¯ on August 14, 1945.

Harrison’s six Hellcats were low over Tokurozama at 6:45 a.m. when they got the cease-fire news.

Decades later, Ted Hansen, who had been flying on Maury Proctor’s wing, told an interviewer that he recalled thinking, “Oh God, let’s get our fannies out of here.”

Seconds later 17 Japanese fighters — Kawanishi Georges and Nakajima Franks along with Zeros and Jacks — assailed the Americans from behind and above.

Harrison turned his flight into the attack and opened fire.

Hansen thought himself a goner, but during the first head-to-head pass he splashed two Franks, one of them about to ram him; Maury Proctor shot the wing off a third.

Hansen and Proctor lost track of Harrison, Hobbs, and Mandenberg, but when they spotted a Jack on Joe Sahloff’s tail, both swung to starboard.

From 700 yards, Proctor exploded the troublesome Jack, but Sahloff’s F6F was smoking and clearly in trouble.

Sahloff headed for the coast but was never seen again.

Proctor had planned to escort Sahloff home until tracers bracketed his own Hellcat.

Knowing Hansen was weaving somewhere above him, Proctor slewed right, allowing Hansen to shoot a Frank off his tail.

When Proctor reversed, he spotted two more bandits in flames and seven Japanese, six ahead, one behind, aiming his way.

Fortunately, the six ahead started to climb, giving Proctor a killing belly shot at one.

After ducking into clouds to elude the bandit on his tail, Proctor flew coastward and tried to radio the other five fliers.

According to Proctor, only Ted Hansen responded — but Hansen recalls hearing nothing from any of the five.

He eventually touched down on Yorktown, certain he was the sole survivor — until Proctor landed five minutes later.

The wild fight over Tokurozama, World War II’s last substantial air battle, interwove victory, tragedy, and irony.

The six VF-88 aviators battled harsh odds to claim nine kills but at the cost of four missing — and finally presumed dead: Howdy Harrison, Hybrid Hobbs, Gene Mandenberg, and Joe Sahloff.

The fallen on both sides died in the opening moments of peace.

In VF-88’s scant month of combat, the unit lost 10 aviators. For all of Air Group 88, including men lost during training, the tally was 31.

The newest Yorktown had deployed so recently that its airmen and sailors remained in the Pacific until October 1945. Only then did the Fighting Lady sail for San Francisco.

Departing the Bay months before, Herb Wood had resolutely ignored the crowds cheering from the iconic bridge spanning the Golden Gate.

This time, though, Wood was on deck, anticipating a welcome, only to realize that the homeland he had defended had made a far swifter transition to peace than he.

“When I returned, having lost all those buddies,” he said wistfully in a recent conversation, “there were only six people waving to us from the bridge.”

This story was originally published in the September/October 2015 issue of World War II magazine, one of Navy Times' sister publications. Subscribe here.