Stephen Decatur was only a teenager when he wrapped his arms around a fellow midshipman who was too injured to raise his pistol or even stand to help him continue a duel.

The midshipman had faced two opponents and was wounded by both, but insisted on fighting the other men he believed had insulted him.

With Decatur’s help, the midshipman aimed carefully and fired, wounding his opponent. Convinced that insults to his honor had been avenged, the duelist collapsed, and his opponents, all fellow midshipmen, nursed him back to health.

Decatur fought his first duel a year later, when he was 20.

He was a fourth lieutenant then, gathering men in Philadelphia for service aboard the heavy frigate United States, when the captain of an Indiaman offered his seamen higher wages and the men abandoned Decatur’s ship.

Because the men had signed contracts, Decatur prevailed legally, but the insults exchanged with the Indiaman’s captain drove him to consult with his father, an officer from the Revolutionary War, about whether a duel was necessary to keep his honor.

His father told him it was. Decatur issued the challenge, and it was accepted. He proclaimed his intent merely to wound his opponent, who was less proficient with arms.

Decatur’s first duel ended well. He wounded his opponent and was unhurt himself.

By 1800, the Navy was losing many men to duels, two-thirds as many as were lost in sea battles.

The Code Duello set forth the rules for dueling on the Continent and in America.

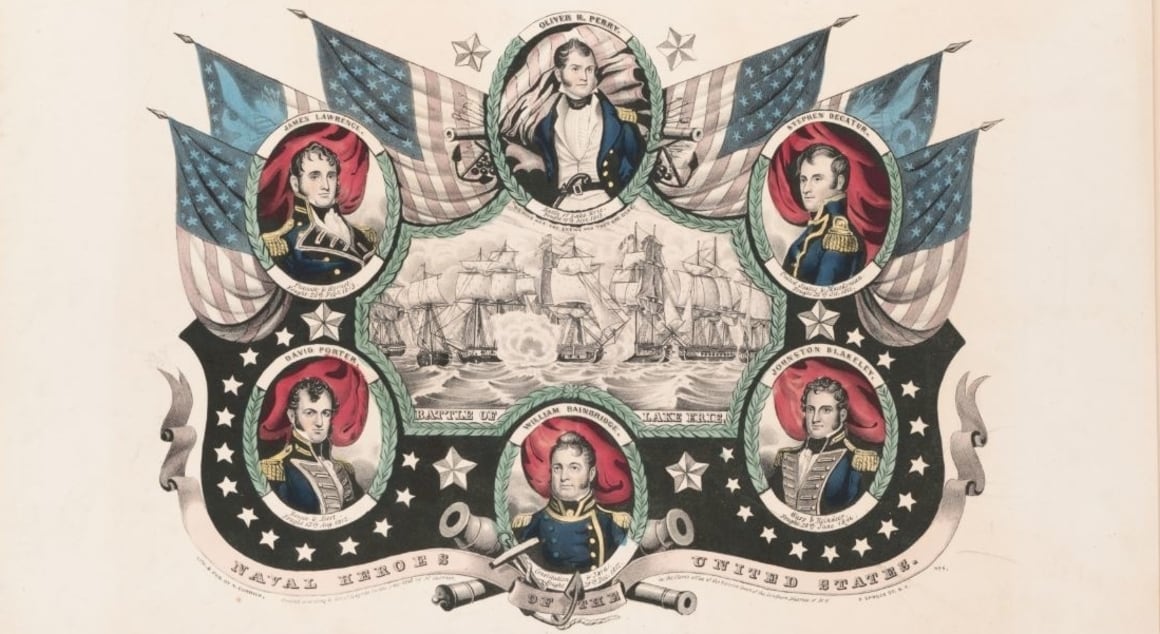

In 1777 a group of Irishmen wrote the first official rules; the rules were tweaked by the Americans, defined for the Navy by Commodore Stephen Decatur and recodified for the public in 1838 by John Lyde Wilson, a former governor of South Carolina.

The rules explained, for example, that the challenged party could choose the location of the duel and that the challenger could end the duel by apologizing.

Each duelist, also called a principal, chose a “second” through whom the details of the duel were discussed.

The seconds were also supposed to try to resolve the dispute without resorting to the duel.

The seconds made sure the duel was fair and the weapons were equal. They were to fetch help if their principal got injured, and to assure that the principals fought with honor.

Dueling came to the United States from Europe as a gentleman’s tradition and a way to protect one’s honor.

It’s no wonder that the Navy took so readily to dueling, as the strict hierarchy resembled its own aristocracy within the new democratic country.

John Paul Jones, the Navy’s first hero of the Revolutionary War, was reluctant to duel. Although he was easily offended and often provoked, he never fought a duel.

When Jones was in the Navy, however, duels were usually fought with swords. Jones, a gardener’s son, never learned the art of fencing, and he may have avoided duels out of self-preservation — he knew his swordsmanship was inadequate.

As time passed, American military men and civilians alike began to duel with pistols instead of swords.

Proficiency with a sword takes years, and only the nobility had the time to devote to the art. Guns were easy to master, inexpensive and easy to obtain.

Americans rejected nobility for meritocracy and in the process rejected the trappings of nobility. They usually used large-caliber smoothbore flintlock pistols with limited accuracy, though duelists sometimes chose shotguns, carbines or rifles.

Most duels involving naval officers used pistols, as they were common to the officers.

The emphasis was on courage, not on killing.

Naval officers lived and often died by virtue of their bravery and pride. Ducking an affront was considered cowardly, whether it was a verbal insult at a social gathering or a cannon barrage from an enemy ship — the officers stood on deck, and to flinch at the incoming lead was to lose face.

So to succeed in a duel, one needed to show up and not flinch at the sound of gunfire and the possibility of being wounded or killed.

Decatur was involved in his fair share of duels as a young officer.

In 1802 he served as a second to his sister’s husband, a Marine captain. The Marine died in the duel.

As a lieutenant, Decatur volunteered as second for one of his midshipmen who was provoked into an unfair duel. The stunned midshipman accepted.

Decatur demanded a fight with pistols leveled at a distance of four paces, far closer than the standard distance of 10 paces.

His midshipman was not proficient with his pistol and could not hope to hit an opponent from so far away. The other duelist and his second were appalled but accepted.

Decatur waited until the other duelist’s hand wavered before calling “Fire.” The man missed completely, while Decatur’s midshipman shot through his opponent’s hat.

The irate challenger refused to concede that honor had been absolved and demanded a second round.

“Aim lower if you wish to live,” Decatur advised his nervous midshipman.

This time the midshipman killed his opponent without being injured.

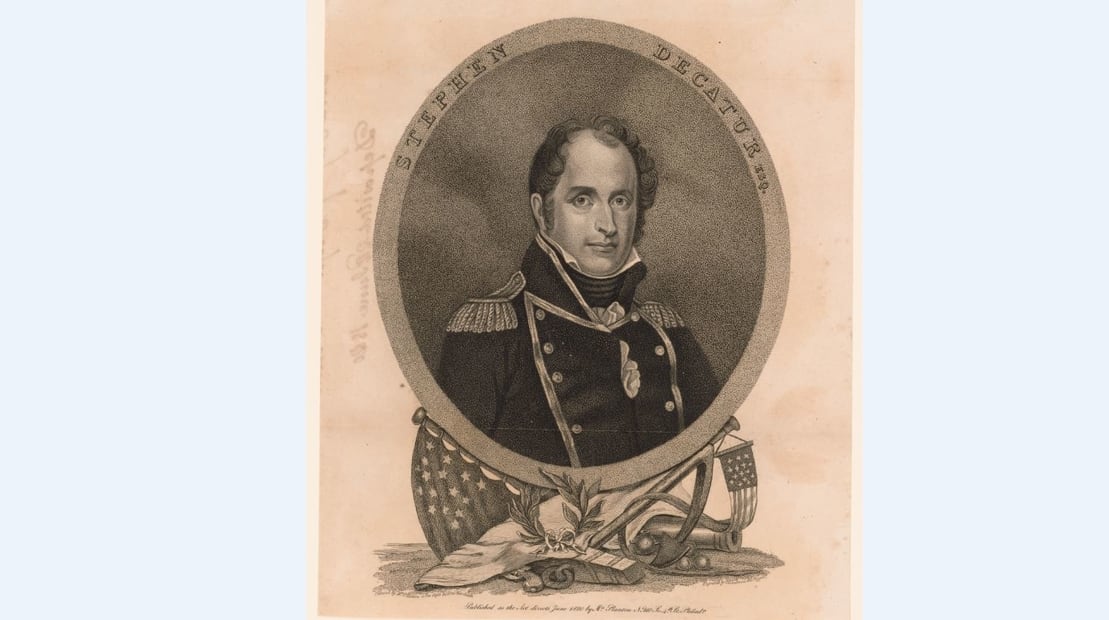

Decatur fought a series of skirmishes with the French during the so-called Quasi-War. He then participated in the first Barbary War against the pirates in the Mediterranean.

During a daring and successful raid on the harbor of Tripoli, he burned the former sailing frigate Philadelphia, which the Tripolitans had captured and made their own, effectively doubling their naval strength.

He had disguised himself and his men as North Africans needing a safe harbor. Decatur’s raiders destroyed the huge ship without losing a single man, and his commodore immediately recommended his promotion to captain.

To this day, Decatur is the youngest man to earn the rank of captain, at the age of 24.

All was not well within the Navy, however.

The British continued to impress American sailors — kidnapping them from their ships and forcing them to serve the crown.

The most egregious offense came in 1807, when the British frigate Leopard confronted Chesapeake, an American frigate, and took three men.

The American Commodore James Barron did not mount much of a defense.

Adding to the insult of the impressments, the British refused to accept his surrender of the ship. That meant Barron had been completely dishonored, as he couldn’t even claim the loss occurred during a legitimate battle.

Decatur served on his court-martial, and Barron was discharged from the Navy for five years. Barron never forgot the insult.

In 1809 Commodore Decatur took command of the United States.

Midshipmen had changed little since his day, and neither had the young officers’ habit of dying in duels instead of combat.

Decatur took steps to eliminate needless bloodshed. As captain, he required that all midshipmen consult with him before declaring or accepting a challenge for a duel.

His goal was not to abolish dueling, since it played a role in maintaining the bravery and honor of the Navy, but rather to eliminate frivolous contests by giving the men a chance to calm down.

The duel in which Decatur served as a second while a teenage midshipman, for example, was started when a group of midshipmen heard Decatur and his friend teasing each other and decided Decatur had been insulted.

Decatur’s friend was offended and challenged the whole group to a series of duels. The Decatur plan did not eliminate these hotheaded duels but did decrease them.

It was ultimately adopted by most other Navy captains.

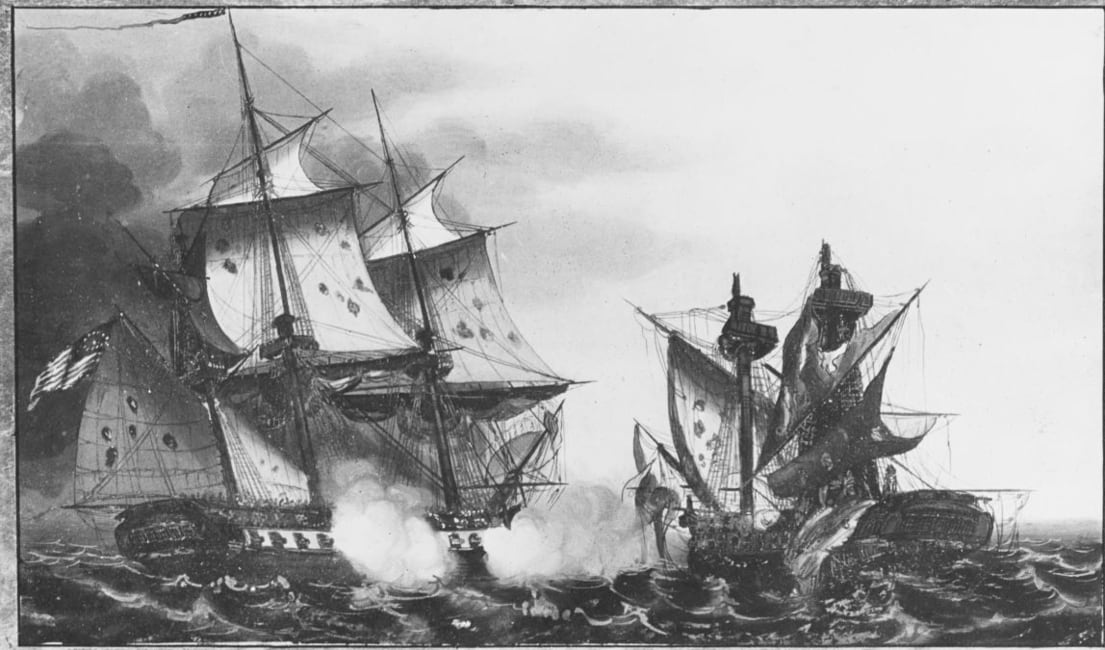

Decatur’s next chance for glory came during the War of 1812, fighting against Britain for “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights.”

While captaining United States, Decatur took the larger frigate Macedonian, to the shock of the British, who thought they were invincible at sea.

He brought his prize home.

In the meantime, the British had blockaded the U.S. Navy, and Decatur’s attempts to sail United States from Connecticut into open water were fruitless.

The secretary of the Navy found it unacceptable that his best commodore had been blockaded for a full year.

Decatur was transferred to the heavy frigate President in New York and made the journey over land to his new command.

His attempt to run through the blockade stalled first when his ship lodged on a sandbar. Finally the tide rose, and he sailed his damaged frigate into open water.

But his escape attempt failed when he encountered four British ships. He ran.

When the British warship Endymion caught up to him, he crippled the lone vessel, and his own ship was damaged in the fight.

But soon the three other British ships were on the horizon, and with no chance of victory, Decatur surrendered.

He was absolved by a court of his peers, though he never forgave himself for the capture of his ship.

Still, the Navy trusted him with command of the ship of the line Independence and instructions to finalize a peace agreement with the Barbary States.

Decatur set sail for the Mediterranean, arriving before the squadron led by Commodore William Bainbridge.

Decatur negotiated peace before Bainbridge could arrive, choosing glory over friendship, perhaps not understanding how hard Bainbridge would take the lost chance at glory.

Commodore Barron reappeared after his 10-year absence abroad, hoping to be reinstated in the Navy.

His chances were slim, with three of the men who served on his court-martial now naval commissioners: Commodores David Porter, John Rodgers and Decatur.

One of his few allies was Jesse Elliott, now a captain but once a midshipman on Barron’s ship when the British boarded, for which Barron was sent to court-martial.

The Navy was willing to accept Barron’s service as sailing-master, in charge of the maintenance of ships, but Barron refused to accept the demotion, and Decatur refused to see Barron in his old rank of commodore.

A series of letters between the two led to Barron challenging Decatur to a duel in 1819.

It would be 1820 before the details were finalized.

Barron chose Elliott as his second.

Decatur had a harder time finding a second. Many of his friends refused to serve, thinking this was an unnecessary dispute between one of the nation’s greatest commodores and a has-been.

This was a problem — according to the Code Duello, the duelist’s second needed to be of similar rank. Had Decatur not finally found a second in Commodore William Bainbridge, who suspiciously arrived in town just as Decatur was getting desperate, the duel may not have occurred.

Decatur’s wife, Susan, never trusted Bainbridge. In fact, after Decatur’s death, she never blamed Barron, the other duelist; she blamed Bainbridge and Elliott, believing they had connived a duel out of jealousy and malice toward Decatur.

Correspondence between Barron and Decatur before the duel supports Susan’s conspiracy theory.

Barron’s second, Elliott, feared that the recently deceased Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry might have left behind documents from Decatur that somehow incriminated Elliott.

Elliott had few friends in the Navy due to his cruelty toward his men (he kept his cat o’-nine-tails soaking in salt water to add to the brutality of lashing); Barron and Bainbridge were among his few allies.

Bainbridge also had reason to be bitter. He had served as captain of Philadelphia, which was taken by Barbary pirates and later destroyed by Decatur in the heroic effort that earned him the rank of captain.

Bainbridge also lost the chance for glory during the second Barbary War. His own ship had been delayed, allowing Decatur to arrive in the Mediterranean before he did and reach peace settlements with the Muslim leaders demanding tribute and taking Americans hostage.

Dueling was banned in the District of Columbia, so residents of the young nation’s capital generally went to Maryland, usually to the fields of Bladensburg, to duel.

At the time, dying in a duel was unlikely. Flintlock pistols often misfired, and a misfire was considered a shot. Even when they did fire, accuracy was a problem with the smoothbore pistols.

The duel Decatur and Barron fought required each man to aim before the duel began. Decatur announced his intention merely to wound Barron.

The seconds measured the distance and loaded the pistols.

Code Duello dictated that all communication take place via the seconds. Barron, however, broke the Code Duello by speaking directly to Decatur.

“I hope that when we meet again, sir, that we should be friends.”

“I have never thought of you as an enemy, sir,” responded Decatur.

It was the duty of the seconds to attempt reconciliation, even at this late juncture.

But neither did. Instead, Bainbridge ordered the men to take aim.

The men fired almost instantaneously.

Barron fell, wounded in the hip.

Decatur stood a few seconds, clutching his gut, color draining from his face, saying, “Oh Lord, I am a dead man.”

He died just hours later. He was 41.

Over three-fourths of the city of Washington attended the funeral of a naval hero who preserved his honor at the cost of his life.

Janine Peterson writes from Virginia. For more on dueling, try: Gentlemen’s Blood: A History of Dueling From Swords at Dawn to Pistols at Dusk, by Barbara Holland; and Famous American Duels, by Don Carlos Seitz.

This article originally appeared in the February 2007 issue of Military History, one of Navy Times' sister publications. To subscribe, click here.