NAZARETH, Pa. — In 2014, Larry Bartram, a software company founder and archaeologist, was at C.F. Martin & Co. in Nazareth to have a guitar repaired. While waiting, he strolled into the factory museum.

Tucked among the many displays, Bartram found a nondescript little ukulele covered with autographs.

Bartram found it stunning that recognizable among the signatures was that of one of his college teachers, the late Laurence Gould, a professor of glacial geology who inspired him.

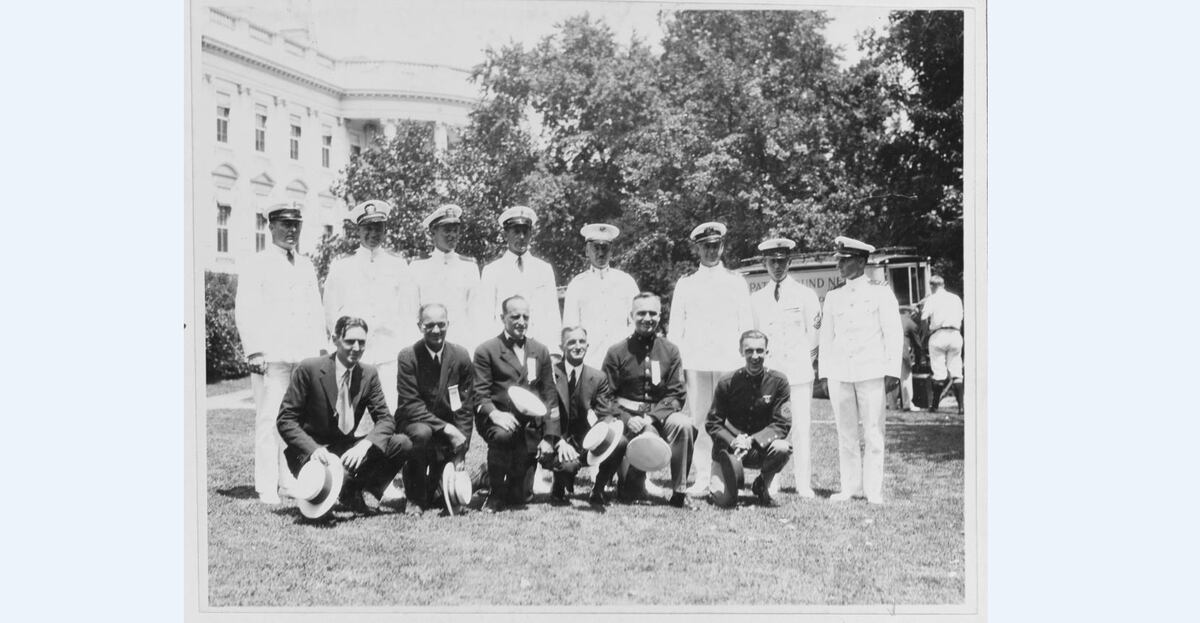

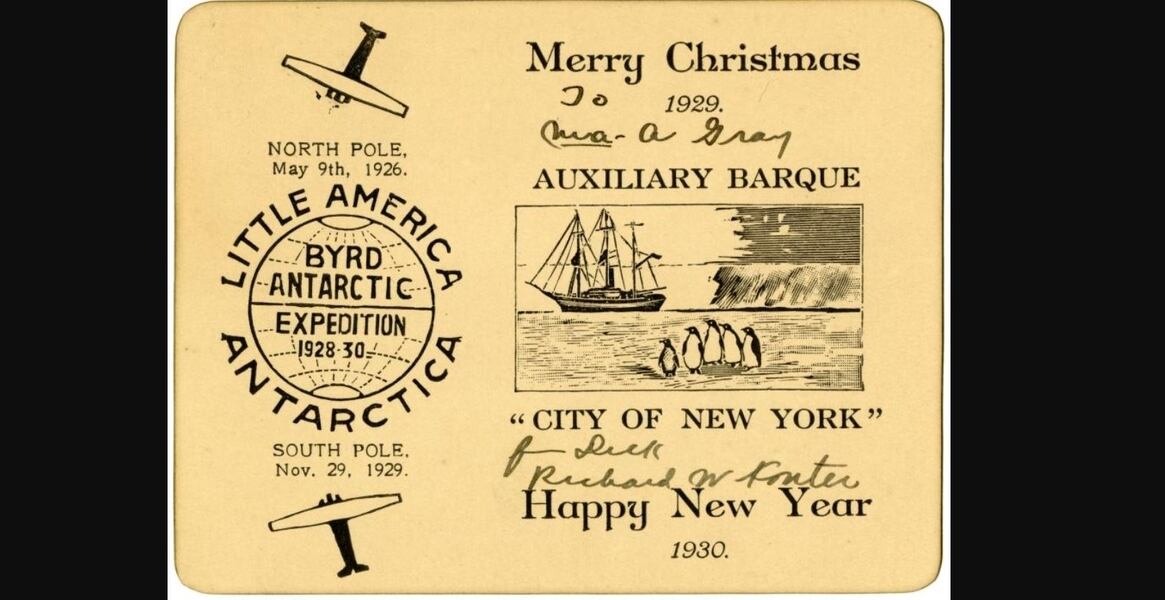

When Bartram returned to collect his guitar a couple months later, he met with Martin archivist Dick Boak, who explained the ukulele belonged to Richard Konter, an integral part of the team of famed explorer Adm. Richard Byrd when he became the first to reach by air both the North Pole in 1926 and, later, the South Pole.

Boak told him the instrument was secreted onto the North Pole plane — the only nonessential cargo aboard — by Konter, a scientist who, as No. 3 in command on Byrd's expeditions, guided those planes and predicted the weather conditions for exploration.

Chief Radioman Konter also was an accomplished ukulele player who wrote instruction books, arranged music for Broadway plays and led the Ukulele Chorus, a group that played throughout New York City.

Gould, Bartram's professor, also was a member of the Byrd expeditions.

It was that connection that started Boak and Bartram on a four-year journey to trace the provenance of the ukulele — which the Martin factory owned since 1952, but about which little was known — and to identify the nearly 160 signatures on it.

Through the journey, Boak and Bartram not only learned about Byrd and the crew members of the expeditions, but how President Calvin Coolidge, legendary explorer Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, Thomas Edison and even the last queen of Romania also came to sign the instrument.

That story of that quest is the subject of a new book, “A Stowaway Ukulele Revealed: Richard Konter & The Byrd Polar Expeditions,” by Bartram and Boak.

The book not only tells the story of the ukulele, but of the people who signed it.

"After the story we found, we couldn't not write the book," Boak said in an interview.

Music for an exploration

Byrd was a naval officer who commanded air forces in World War I and went on to become an aviation pioneer, leading an early crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. But it was the polar expedition that made him a national hero.

In 1926, Byrd organized an expedition that was to become the first to reach the North Pole by air.

On his crew was Konter, a Navy veteran of 30 years who served in both the Spanish-American War and World War I.

He also was an accomplished ukulele player, arranger and bandleader who worked with Tin Pan Alley composers and publishers, arranging and creating the ukulele tablature for many popular songs.

"The Stowaway Ukulele" says that when Byrd asked Konter to be a part of the Arctic expedition, "it was Konter's naval record and abilities that secured him a place on the crew," but his musicianship "sure didn't hurt his chances."

In fact, Boak said in an interview, Konter "was one of the greatest ukulele players to ever live. He was a magnificent player. . Not only did he play, he was the sole source of entertainment aboard the expedition."

The expedition, ferried to the arctic by ship for staging, lasted many months, Boak said.

Boak said Konter promised he would take photographs and names of all of the members of his Ukulele Chorus with him on the flight. He stuffed those names in the Martin ukulele, which he bought shortly before the expedition, and conspired with Byrd's pilot, Floyd Bennett, to smuggle aboard the plane.

"The problem was all the crew members had tried to smuggle things on board the plane, and they discovered that there was some 200 pounds of souvenirs on board, and it would probably have caused the plane to crash or not be able to make it to the North Pole," Boak said.

“So they unloaded all this crap from the plane, except that Floyd Bennett didn’t tell anybody that he had the ukulele packed in furs under his seat. It’s the only artifact that actually went to the North Pole.”

After the mission was complete, all 45 crew members signed the ukulele.

"As unlikely as it seems," the book says, "Konter's ukulele had become the ultimate souvenir of an important era."

The expedition made its participants heroes. Byrd received the Medal of Honor.

"People who went on the expedition were not typically very important, but after the expedition, many of the crew members actually went on to become very, very important people," Boak said.

Konter also was part of Byrd's 1929 first expedition to the South Pole, and got most members of that expedition to sign the instrument as well.

"I think he clearly he knew that the Byrd expedition was going to be historically important, and I think it was kind of like an autograph book," Boak said.

More autographs, and then a trade

Over the next few years, Byrd's teams frequently were feted, and Konter made it a point to get the autographs of more important people on the ukulele.

Coolidge, Lindbergh and Teddy Roosevelt Jr., who was secretary of the Navy, all signed it. So did Helen Mack, the lead actress in the movie "Son of Kong," in which she plays a ukulele; musician Harry Armstrong, who wrote the music to the barbershop quartet standard "Sweet Adeline"; and Charles Frohman, a major producer of Broadway shows for whom Konter likely arranged ukulele music during the Roaring '20s, which Boak said was the pinnacle of the ukulele.

He stopped adding to the collection about 1930.

Boak said his and Bartram’s research found Konter established correspondence with C.F. Martin III during the 1920s, when Konter wanted to be a ukulele dealer.

The company really didn’t do that — it required dealers to have its full line in stores, Boak said, and “Konter didn’t have a store; he just wanted to buy ukuleles cheap.”

Konter didn't marry until he was 70, to Joanna Cohen, whom he romanced when he was 36 and she just 17.

Boak said Konter proposed to her on the night before he left for the North Pole expedition, but Cohen’s "father said, ‘Absolutely not; he’s too old.’ "

While he was away, one of his friends, “Battleship” Bill Poole, who also signed the ukulele, married Cohen.

"It kind of broke Konter's heart, but he became friends with them before they were married, and he stayed friends with them throughout their marriage," Boak said.

Konter and Cohen married after Poole died and were together for more than 20 years until his death.

Boak said Cohen "was a great musician and she wanted a Martin guitar."

"In 1952, Konter ... proposed trading the ukulele for a Martin D-28. Which in hindsight was clearly to Martin's advantage," Boak said.

“I’m sure Konter placed a high value on the ukulele, given the effort he placed into it. But he was an older man. He was probably worried about what the future of the ukulele would be and he probably thought that Martin would understand its value and take good care of it.”

In Martin's hands, the ukulele promptly "went into a closet for probably a decade or two," Boak said.

Seeing the handwriting

Boak said the ukulele eventually was put on display in the Martin museum, which originally was a small room, but which grew into a big display.

Boak said he previously started to try to identify the names, "but I didn't get very far."

He also had an apprentice who, working online, “found five or six of the really obvious ones.”

"We knew Calvin Coolidge and we knew Admiral Byrd and we knew Floyd Bennett, and we knew couple of the others," Boak said.

But when Bartram returned to pick up his repaired guitar, he brought with him professor Gould's book "Cold," about the polar expeditions.

"We grabbed the ukulele and went up to the computer," Boak said. "We looked in the index of Larry Gould's book, and in the index were the names of everybody associated with the expeditions, all the crew members and everything.

"And in the course of about an hour, we had identified about 40 names, and we were just floored. But then there's 160-some signatures on the ukulele. So we just became obsessed with it," he said.

Many of the autographs faded over 90 years. And because an instrument isn't an ideal medium for autographs, many were distorted to begin with.

Boak said that to get the signatures to stick to the ukulele, Konter had to scrape away the lacquer "to create a sort of an abraded surface."

During a visit to the White House, for example, "he scraped away an entire section above the sound hole because he knew he might be able to get Calvin Coolidge's signature. And he got Coolidge, and then he got the vice president, and then the secretary of state and then Gen. "Blackjack" Pershing and Charles Lindbergh. And they all signed one after another in that area," Boak said.

It also became evident to Boak and Bartram that Konter relegated related autographs to specific areas. For example, all of the expeditions' participants signed in the same area, making them easier to identify.

"When we realized that, we looked up the names of all the crew members and we had all of their signatures from the ship's manifest, and we simply went down the list," Boak said. "And we got them all."

One autograph that initially stumped Boak and Bartram was that of Marie, the last queen of Romania, which is on the ukulele's headstock. Boak said Martin's former historian, Mike Longworth, believed the name was of the cook on Byrd's ship.

But research revealed the cook was a man.

At first, Boak believed it to be Marie Peary, who, as the daughter of arctic explorer Admiral Peary, was known as "the snow baby."

But she already had signed the front of the ukulele.

"It wasn't until our research in the Byrd polar archives that we scanned two invitations to Adm. Byrd to attend a reception for the queen of Romania. And we saw clearly Marie's signature, and it matched the signature on the headstock exactly," he said.

Detective work, and the findings

Much of the work Boak and Bartram did, and much of the book's story, involved tracking down the other signatures. It was like modern forensics.

"The signatures were very, very difficult, and there was a lot of what I call reverse engineering," Boak said.

Using a graphics tablet and laser engraving, he inked each signature and was able to magnify them.

"There was a tiny signature on the front of the ukulele, and I could see it from the high-resolution photography there clearly was an 'A' at the beginning, and it was an unusual 'A.' " Boak said.

"After the 'A' looked like an ‘L,’ and then at the end of the first name I saw an ‘A.’ . And then the first letter of the last name, I could clearly read was an ‘E.’

"So I said, 'Could it possibly be Amelia Earhart?' So online, I looked up her signature, and I saw that her 'A' was exactly the same as the 'A' on the ukulele. And then knowing it was probably Amelia's signature, I could kind of see the rest of the letters," he said. "And I have to tell you, that happened several times."

Directly above Earhart was another problematic signature, with a first word that "was either Major or Mayor," Boak said. "The first name seemed to be Edw---. Well, it sounded like Edward. And the middle initial was H, and the first letter of the last name appeared to be an L.

"So I Googled 'Maj. Edward H.L.' and nothing came up. I Googled 'Mayor Edward H.L.,' and immediately a picture of Amelia Earhart came up from Medford, Mass. And standing next to her was Mayor Edwin H. Larkin, the mayor of Medford, where Amelia Earhart lived. And that's why their names appeared together on the ukulele," he said.

Boak and Bartram got a grant from the Smithsonian Institute and the National Archives to use a multispectral process to see signatures that had faded from visibility under normal light. They also were able to go through Konter's papers, which he donated to the National Archives, and some of Byrd's papers, as well.

They also visited Konter's stepdaughter, Boak said, and spoke to her "about everything about his life and about their life together and about his verbal recollections about the expedition and everything. And about his personal friends, many of whom were members of the Ukulele Chorus."

Boak said he and Bartram even uncovered some things likely unknown.

"The story of the Byrd expeditions has been told and retold in many, many different aspects," he said. "But we discovered that (Konter) was a remarkable photographer, and his photographs added a tremendous amount to the whole Byrd story. A lot of photographs had not been seen before. Some had been sent to Byrd and lost."

Boak also said they learned through correspondences between Konter and Byrd that there was a falling out between them. Boak said Konter became depressed, then "really incensed and angry and decided he didn't want to have anything to do with Byrd ever again.

"But I think he came out of that depression. . That was information that nobody ever would have known without going through Konter's papers. I don't anyone had ever gone through them before," he said.

They also learned that Konter tried to get President Franklin D. Roosevelt's autograph, which Roosevelt typically didn't give, Boak said.

"Roosevelt sent a letter to Byrd saying, 'Hey, I got this letter from Konter, who wants me to sign his ukulele. Is this important?' And Byrd answered back and said, 'It's up to you whether you want to sign. Many important people have.' And Roosevelt consequently didn't sign the ukulele. Which was very disappointing to Konter," Boak said.

There remain a handful of signatures that have evaded identification, especially some on the back of the ukulele, "which tends to have people who are less famous," Boak said.

He said he hopes "to figure this out in the next decade. . We think that probably will happen."

In the meantime, C.F. Martin created a replica of the ukulele that it is selling for $2,499. They are made to order, and at last check 46 have been sold, Boak said.

DETAILS

"A Stowaway Ukulele Revealed: Richard Konter & The Byrd Polar Expeditions"

A book about historic C.F. Martin & Co. ukulele that traveled to the North Pole with Adm. Richard Bird and was signed by the crew, as well as by dignitaries such as Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh and the queen of Romania.

By Larry Bartram with Dick Boak

Hal Leonard Books, 2018, 300 pp. $27.99