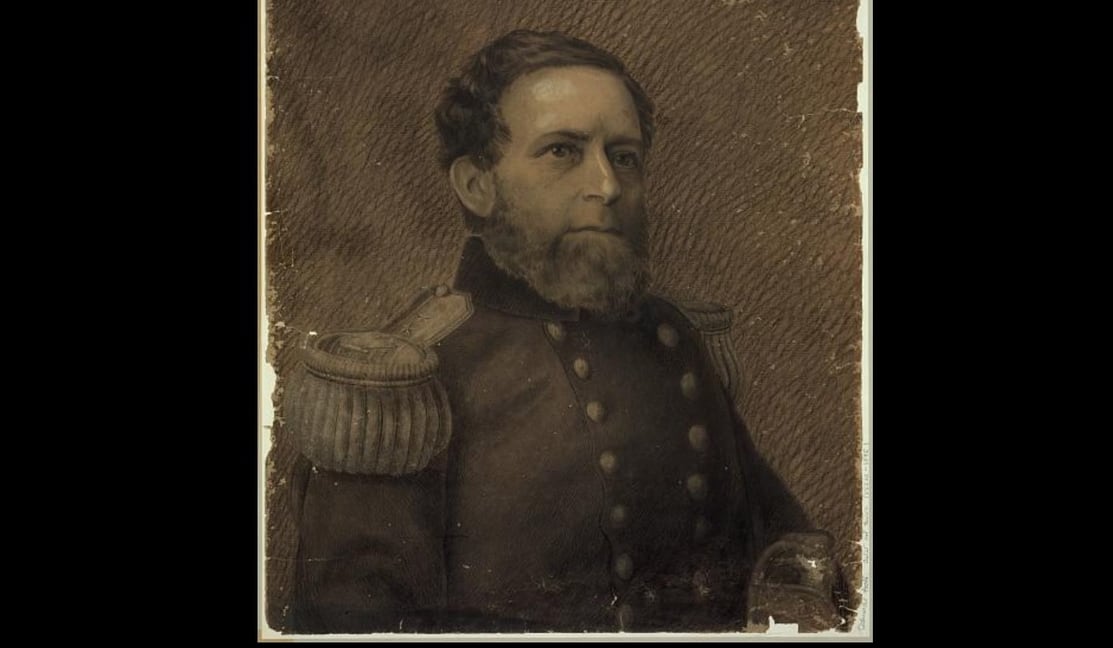

In late November 1856, Cmdr. Andrew Hull Foote of the U.S. Navy’s East India Squadron sat in his stateroom aboard the sloop-of-war Portsmouth, mulling over the deadly events of the previous week.

He had personally led ashore a small but determined force of Marines and sailors against overwhelming odds, capturing four heavily defended enemy forts and fending off several vicious counterattacks.

The fighting had been brutal, resulting in the deaths of 10 Americans and the wounding of 22 others.

In the hard-won victory the Marines and sailors had acquitted themselves in the finest traditions of the U.S. armed forces, and they would be heralded as heroes both at home and abroad.

Yet they had intervened in a conflict in which they were not supposed to be involved.

The United States had been a neutral bystander in a controversial war pitting the British and French against Qing dynasty China over the trade of a dangerous narcotic.

So just how did Foote come to break his country’s neutral stance and become embroiled in a foreign war despite orders to the contrary?

Britain had initiated the 19th-century First and Second Opium Wars, as the name implies, in part to force Qing authorities to permit British merchants to trade in Indian-grown opium.

For centuries the Chinese had used the drug for medicinal purposes. It had since become increasingly popular for recreational use, and countless Chinese had become addicts, resulting in widespread health issues and fueling an explosive growth of drug-related crime.

During this period the British obtained their beloved tea mainly from China rather than growers in India, and China was also the source of silk, porcelain and other exquisite goods hugely popular in Britain. But there was no real balance of legal trade, as Britain simply had nothing the Chinese wanted in exchange.

Complicating matters was a monetary consideration. The only payment Chinese merchants trusted was Spanish silver, but when Spain supported the nascent United States in the Revolutionary War, the British could not obtain that precious metal.

Chinese merchants were more than willing, however, to accept payment in another commodity the British produced in abundance — opium. Silver was soon flowing out of China as fast as highly addictive opium flowed in.

Things came to a head in 1839 when Chinese authorities finally took active measures to stamp out the opium trade, issuing imperial edicts banning its import and threatening harsh punishment for anyone flouting the law.

Chinese Viceroy Lin Zexu also confiscated nearly 3 million pounds of opium without compensation, confined British traders to their holdings in Canton and cut off their supplies.

In response Britain dispatched a military force.

The result was the First Opium War between the British and Chinese empires, which ended in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking — the first of a series of accords the Chinese deemed the “unequal treaties.”

It forced China to compensate British merchants for the seized opium, opened additional ports to trade and ceded Hong Kong to Britain as a crown colony.

It did not, however, resolve the status of the opium trade, leaving merchants subject only to the authority of their own nations’ consuls.

An interlude of almost 14 years followed, but tensions again flared up in October 1856 after Chinese troops boarded Arrow, a British-registered cargo ship, on suspicion of piracy and arrested most of its crew.

British officials protested and demanded the sailors’ release.

Local Chinese authorities freed some but not all of them, and war once again ensued. This time the French participated, under a flimsy pretext of protecting their missionaries working in China.

At the onset of the Second Opium War the U.S. government declared itself neutral.

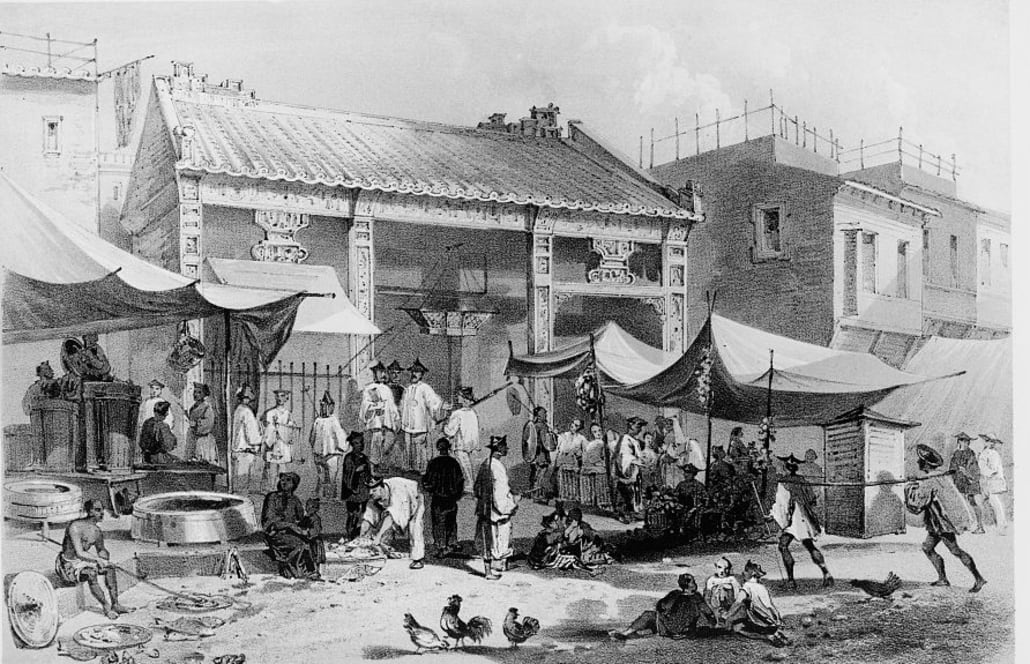

That said, the United States did have a number of its citizens and property — offices and warehouses known as factories — in the port city of Canton, where it carried out foreign trade with China.

In late October 1856, fearing for the safety of employees at the American factory, the U.S. consul requested protection from the U.S. Navy.

Cmdr. Foote responded by sailing Portsmouth to the Whampoa anchorage, a dozen miles east of Canton, and sending ashore a force of 81 Marines and sailors.

The Americans took up defensive positions around the factory, erecting barricades and posting guards on rooftops and at other key locations.

Within days the sloop-of-war Levant landed an additional 69 Marines and bluejackets.

Before putting forces ashore, Foote heard the American flag had been unofficially raised over Canton, prompting him to issue the following circular on Oct. 29:

[I have] been informed that the American flag was this day borne on the walls of Canton through the breach effected by the British naval forces. This unauthorized act is wholly disavowed by the undersigned, in order that it may not be regarded as compromising in the least degree the neutrality of the United States.

The United States naval forces are here for the special protection of American interests; and the display of the American flag in any other connection is hereby forbidden.

Foote ordered his landing parties to avoid armed confrontation with the Chinese and keep the peace — a delicate task they managed to carry out over the next few weeks.

In the meantime Commodore James Armstrong, commander of the East India Squadron, arrived at Whampoa from Shanghai aboard the frigate San Jacinto, sending ashore his own landing party.

Concerned the United States might be drawn into the conflict, he first secured assurances from local authorities and then ordered Foote to remove all his men from Canton. The young commander immediately set to work, but on Nov. 15 the situation went from bad to decidedly worse.

Chinese gunners in a fort ashore fired on a rowboat carrying Foote to a conference with Armstrong aboard San Jacinto.

“When within point-blank range of the fort commanding the passage, a shot was fired, which fell a short distance from the boat; this was soon followed by another, which struck still nearer the boat and ricocheted far beyond it,” Foote wrote in his official account of the incident.

“Mr. [Robert] Sturgis [U.S. vice consul and partner with the American trading firm Russell & Co.] in the meantime waving the flag that it might be fully displayed, and I firing my revolver toward the fort and giving the order to pull away.”

The boat soon passed out of range of that fort, only to come under fire from another.

“We soon passed beyond range of the fort,” Foote recalled, “and when within 200 yards of the next it opened upon us with two successive discharges of round shot and grape, which fell thick and fast around us, one of them striking the water within two blades of the oars; the last discharge was made after the boat’s head was turned toward [San Jacinto].”

It remains unclear whether the Chinese were ordered to open fire on the American boat or if Foote and his comrades were mistaken for British troops.

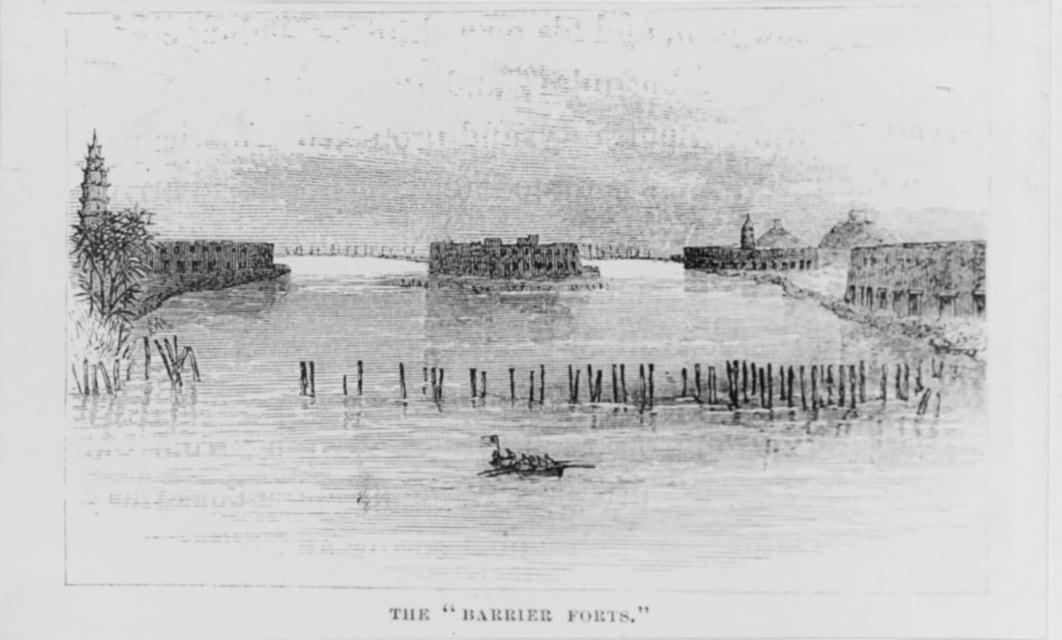

Regardless, Armstrong felt there was no other course of action but to retaliate for the gross insult to the flag, and he resolved to destroy all four of the Chinese barrier forts at the entrance of the Pearl River channel leading to Canton.

On Nov. 16, with Armstrong aboard, Foote sailed Portsmouth to an anchorage within range of the nearest and largest barrier fort and opened a bombardment that stretched until darkness.

The Chinese gunners holed the frigate six times before quitting, possibly after running out of ammunition.

Little else occurred until 6:30 a.m. on the 20th, when Portsmouth and Levant opened a concerted fire on the two nearest forts.

The Chinese retaliated, and the exchange continued for more than an hour.

Meanwhile, Foote formed a storming party of 287 officers, sailors and Marines pulling four field howitzers.

Foote led the formation, the detachments from San Jacinto and Levant under Cmdr. Henry H. Bell and Cmdr. William Smith, respectively, and the Marines under Brev. Capt. John D. Simms. The men boarded rowboats, formed into three columns and headed toward the nearest fort.

Just as the boats touched shore, the accidental discharge of a Minié rifle killed two apprentice boy sailors.

Shrugging off the heartbreaking loss, the storming party pressed on, dragging the heavy howitzers across rice fields and wading through a waist-deep creek.

Foote had decided to attack from the rear of the fort, and his men had to first pass through a small village.

As they did, the Chinese directed a hail of small-arms fire at them, but the howitzers soon cleared the streets of all resistance.

“When near the fort the soldiers were seen fleeing from it, many of them swimming for the opposite shore,” Foote recalled. “The Marines, being in advance, opened fire upon the fugitives with deadly effect, killing some 40 or 50. The American flag was planted on the walls of the fort by a lieutenant from Portsmouth.”

This time it was official.

Foote and his men captured 53 cannons of various calibers, and the Americans put several of the Chinese guns into action against the next enemy fort in line.

Its gunners managed to sink Portsmouth’s launch (though it was later refloated) before being compelled to cease fire.

Even as Foote and his men bombarded the second fort, several thousand Chinese troops advanced from Canton.

Twice they attacked, the Marines pouring fire into their ranks, and one of the howitzers pounding them relentlessly until they fled.

During the action several men from Portsmouth were wounded, while upward of a dozen Chinese were killed.

At 6 a.m. on Nov. 21 Portsmouth and Levant commenced a bombardment of all three remaining forts, sparking another furious exchange of fire.

“The fort nearest the ships having been silenced, at 7 o’clock the boats in tow of the American steamer Cum Fa, temporarily in the charge of Mr. [William M.] Robinet, left the ship and proceeded toward the object of attack,” Foote wrote.

“While passing the barrier, a ricochet 64-pound shot from the farthest fort struck the boat abreast of my own, completely raking it and instantly killing James Hoagland, carpenter’s mate, and mortally wounding William Mackie and Alfred Turner, who died soon after. Seven others were also wounded more or less severely.”

On landing, the sailors and Marines, under Chinese fire, waded through waist-deep water along a ditch toward the second fort. They soon captured it.

“A corporal of Marines, the standard-bearer of the company, planted the American flag upon the walls,” Foote recalled.

“Several of the guns of the fort, with our own howitzers, were brought to bear upon the center fort commanding the river, which had opened fire upon us. It was soon silenced. The other guns in the fort we had captured, which were altogether 41 in number, were spiked, their carriages burned and everything destructible by the means in our power destroyed.”

Foote immediately shifted his attention to the third of the barrier forts.

By 4 p.m. the Marines had captured a riverside breastwork of six guns. The Chinese soon counterattacked, hundreds of their soldiers directly assaulting two companies of U.S. sailors.

Despite the lopsided odds, the latter repulsed their attackers with an intense fusillade of small-arms fire. Spotting an even larger enemy force massing around a pagoda, the sailors harried the Chinese with one of the howitzers until they dispersed, carrying off their dead and wounded.

“The boats, under fire from the fort on the opposite side of the river, had been tracked up to the breastwork,” Foote wrote. “And now, under cover of its guns and those of the fort just captured, they crossed with the party to the island and took possession of its fort, containing 38 guns; one of these was a brass gun of 8-inch caliber and 22 feet 5 inches in length. The standard-bearer of Marines was again the first to plant the American flag upon the walls.” Three down, one to go.

With the third fort captured, the sailors and Marines diligently carried out the same work of destruction they had wrought on the previous two.

While the men went about their allotted tasks, they suddenly came under fire from the fourth and final fort on the north bank near Canton.

Foote’s men again put the recently captured Chinese guns into action against their former owners and, with the field howitzers adding their weight to the fire, silenced the last fort’s guns within a half-hour.

Preparations for the assault on the final fort began at 4 a.m. on Nov. 22. Soon after daybreak a lieutenant in charge of the third fort fired a single howitzer round at the fourth in order to draw the fire of the Chinese.

As the enemy seemed unwilling to expend precious ammunition, Foote ordered another round fired at the fort, which again met with no response.

Undeterred, the commander pressed his attack.

“Three howitzers were left in the [third] fort to cover the landing and prevent the enemy from firing the guns trained on the point which we were to double,” Foote recalled.

“Our launch, with the howitzers, preceded the other boats, which followed in three columns. The howitzers commenced playing briskly to divert the fire of the fort from us. But from the moment we doubled the point, and during the time intervening until we reached within musket shot and gave three cheers — notwithstanding the rapid and effective fire of the howitzers in the fort and the launch — the hostile fort opened and continued a brisk fire upon the boats with round shot, grape, and gingals [swivel guns]. The shot passed closely over our heads, with the exception of three, one of which passed between the two boats, and each of the others striking an oar.”

It was not possible to draw the boats close to shore, so the sailors and Marines were forced to jump into the water.

As the Americans splashed toward the shallows, the Chinese defenders abandoned their positions. While securing the fort, observant sailors noted the fleeing enemy had trained their guns on the landing boats and fitted them with slow-burning fuses.

Fortunately for Foote and his men, the guns were captured before the fuses ran down.

A boatswain’s mate from Portsmouth had been first to enter the fort, proudly raising a fourth American flag over its walls.

Again Foote ordered the fort destroyed, its 8-foot-thick granite walls demolished. The Americans seized 38 guns, bringing the total number captured from the four forts to a staggering 176 pieces.

The barrier forts, the key defense of Canton, had fallen to American forces — not to the British, as Chinese defenders had feared.

In the predawn darkness of the 23rd, Chinese forces from Canton launched a final desperate counterattack.

“An attack was made upon the rear of the fort occupied by our force at 3 o’clock this morning by a body of Chinese, who threw several rockets and stinkpots,” Foote reported. “The assailants were provided with scaling ladders. They were soon dispersed by a brisk fire of musketry and the howitzers, leaving two ladders behind them in their retreat.”

Though he had violated his nation’s neutral stance in the Second Opium War, Foote received widespread praise for his decisive and gallant actions in what came to be known as the Battle of the Barrier Forts.

Secretary of the Navy James C. Dobbin wrote Commodore Armstrong on Feb. 27, 1857:

This trifling with our flag would probably have been repeated and led to still more serious consequences.…I approve, therefore, of the course pursued by you and those under your command. The brave and energetic manner in which the wrong was avenged is worthy of all praise. The gallantry, good order and intelligent subordination displayed by all engaged in the various conflicts with the enemy; the precision and admirable success with which the guns were managed, are highly creditable to the service.

Even the British Parliament recognized the skill and gallantry the Americans had displayed during the action.

Foote did draw some criticism for his involvement.

Chaplain James Beecher, an American missionary in Canton, wrote critically of the affair, arguing Foote was “overready to fight.”

Foote responded sharply in defense of his actions:

The fact of the trade of all nations being suspended; the fact that we are not at war with China; that French armed boats, as well as boats of different nationalities, were passing the “barrier forts” unmolested, as they had a treaty right to do, before and after my own boat was fired upon, show your general views to be as crude as they are perverse where the honor of your country’s flag is involved.

Today Rear Adm. Andrew Hull Foote is better remembered for his actions in command of the Mississippi River Squadron during the American Civil War. Yet his assault on Canton’s barrier forts remains a fascinating, if almost forgotten, event in U.S. naval history.

British military historian Mark Simner is a regular contributor to several U.K.-based magazines. For further reading he recommends Life of Andrew Hull Foote: Rear Admiral United States Navy, by James Mason Hoppin; The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of Modern China, by Julia Lovell; and The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another, by W. Travis Hanes III and Frank Sanello.

This article originally appeared in the Oct. 25, 2018 edition of Military History, one of Navy Times’ sister publications.