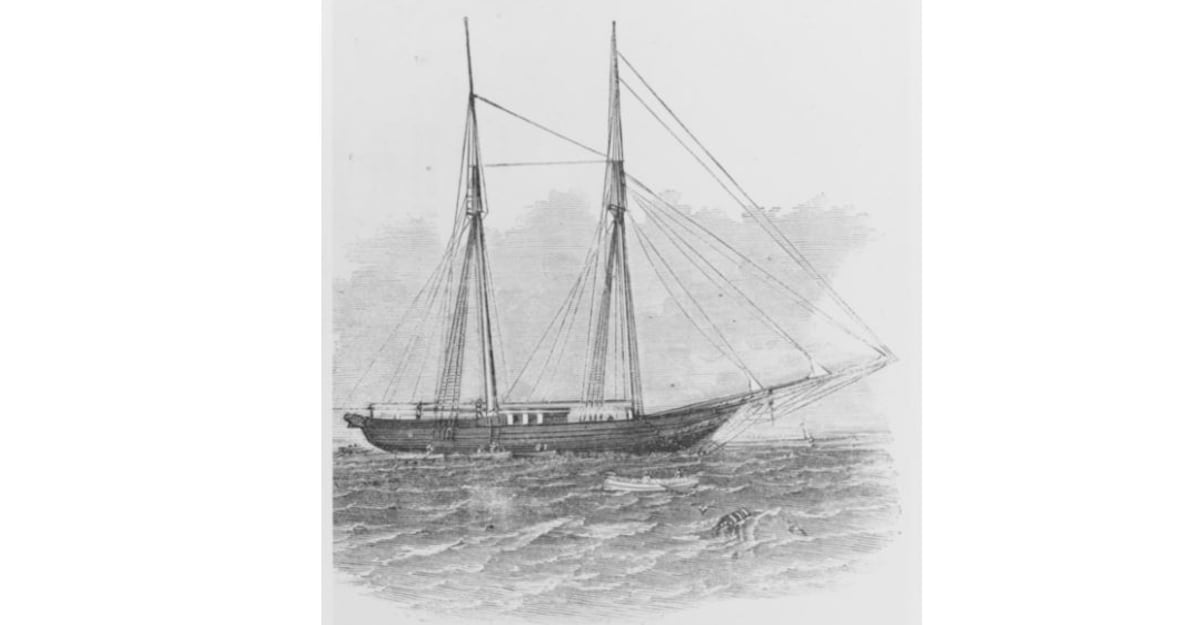

Steward William Tillman had been waiting for more than a week to take back his freedom after Confederate privateers from the ship Jeff Davis had captured and boarded his vessel, the schooner S.J. Waring, on July 7, 1861.

The Rebels were piloting Waring back to a Confederate port with the intent of claiming prize money and selling Tillman, a free black, into slavery for additional profit.

But Tillman would have none of it.

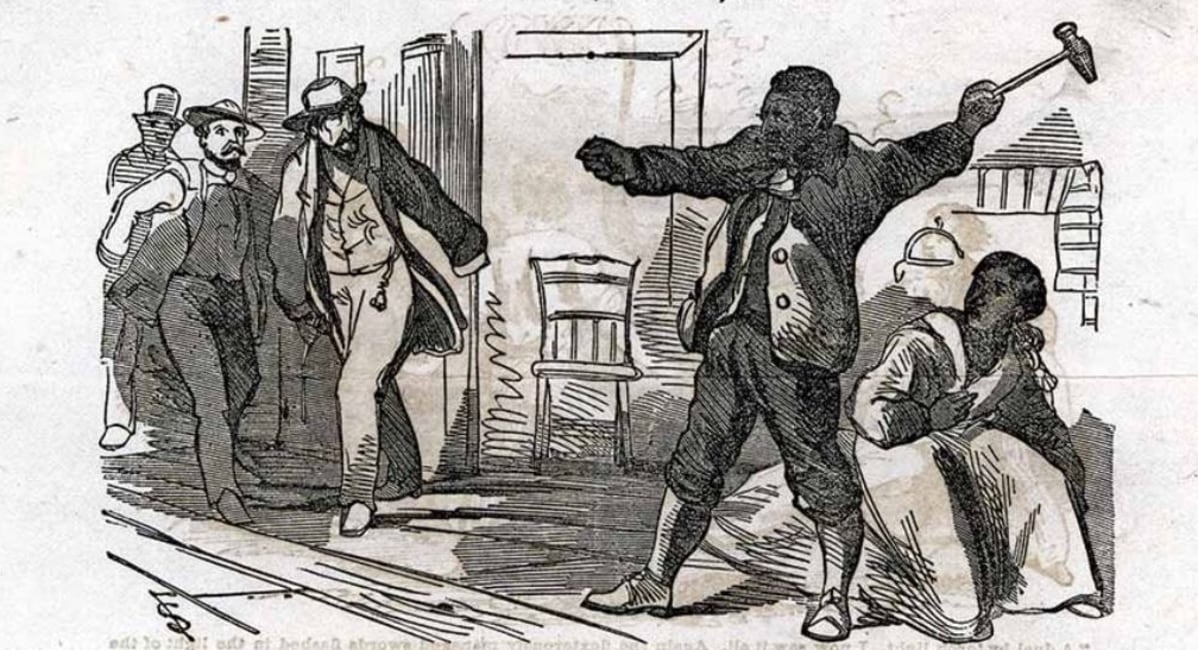

On July 16, he slipped into the cabin of the Southern prize master who was leading Waring’s prize crew, raised high a hatchet he had secreted away, and brought it crashing down on the Southern seaman’s head.

Before 10 minutes had elapsed, two other Confederate crewmen had been killed with the same bloody hatchet. Tillman had effectively taken over the ship. Now what would he do?

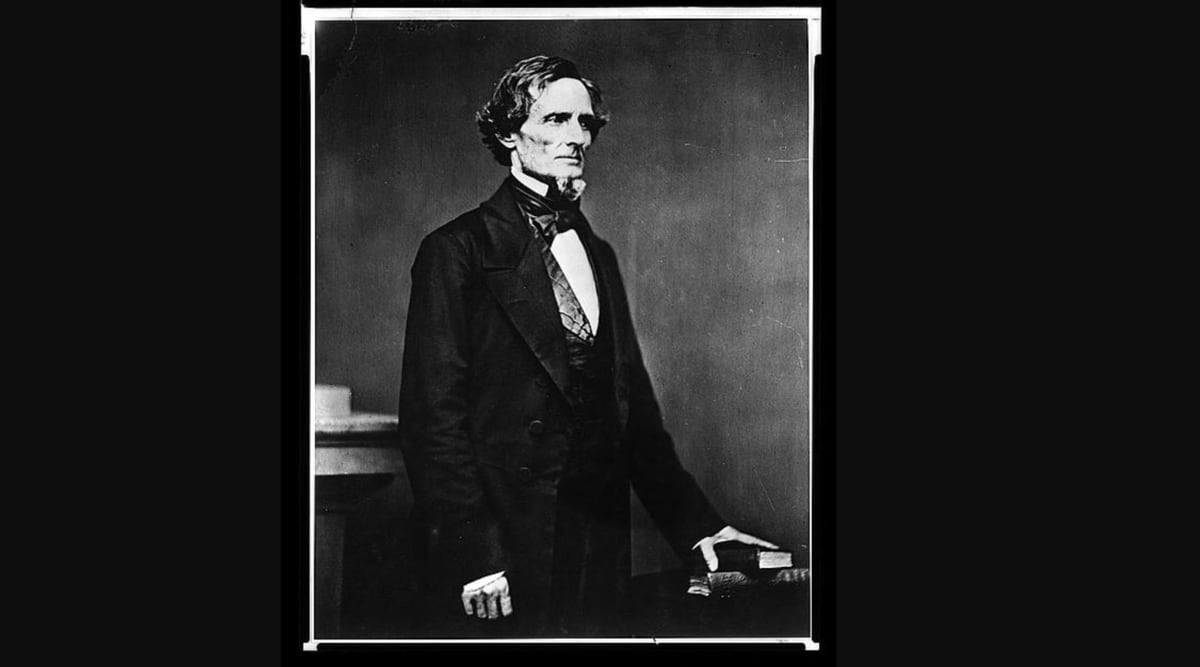

The Southern sailors who had captured Tillman’s ship were sailing under a letter of marque issued by Confederate President Jefferson Davis that permitted Jeff Davis (sometimes called the Jefferson Davis) to act as a privateer on behalf of the Confederacy.

Traditionally, nations without a strong navy — like the Confederacy — relied on private seamen to attack enemy merchant ships. Armed with letters of marque, these sailors claimed legitimacy under the nation for which they sailed.

But Abraham Lincoln refused to recognize these sailors as lawful belligerents, and on April 19 he issued a proclamation stating captains and crews of Rebel privateers would be treated as pirates.

Lincoln’s proclamation gave little pause to ardent Southern seamen, however, and soon many ships like Jeff Davis were leaving from Confederate ports to prey on Union shipping.

Jeff Davis struck quickly, capturing Enchantress on July 6, and then snagging S.J. Waring the next day.

S.J. Waring had departed New York for Buenos Aires on July 4, and on board were the captain and mate, black steward William Tillman, a 23-year-old German seaman named William Stedding, a British sailor named Daniel McLeod, and a passenger named Bryce McKinnon.

Tillman would ultimately become the most consequential man aboard the ship. A 27-year-old native of Delaware who had lived in Providence, Rhode Island, since he was 14, he had been working as a sailor for the past decade.

Standing 5-feet-11 with an athletic build, one observer described Tillman as having a “high, open forehead, and pockmarked features.”

Others would recount that they could “see by the glimmer of his beaming eye, that he possessed within him a large amount of the high mettle and calculating mind peculiar to a courageous man.”

On July 7, Jeff Davis captured Waring. The captain, two mates, and two of Waring’s seamen were taken aboard Jeff Davis, while a prize crew consisting of a prize master, two mates, and two seamen took control of the captured vessel.

The officers of Jeff Davis chose to leave Tillman on Waring, figuring they could sell him in Charleston, S.C., for a hefty sum.

Initially the Rebels treated Tillman kindly as part of their deceit. The prize master told him that he would be “well rewarded in Charleston” for helping bring the ship into port.

Another member of the prize crew told him, “When you go down to Savannah, I want you to go to my house, and I will take care of you.”

Tillman replied politely, saying, “Yes, sir; thank you,” as he doffed his hat.

But Tillman afterward told Billy Stedding, “I am not going to Charleston a live man; they may take me there dead.”

Tillman’s intuition proved prescient. At one point he overheard the prize master say to another member of the crew, “You talk to that stewart [sic], and keep him in good heart. By God, he will never see the North again.”

The captain became more direct with Tillman, telling him “that he would yet see me down in Savannah, and there he would deal with me as he pleased.”

At that, Tillman thought to himself, “Old man, you will never catch me down there.” Indeed, the prize crew would come to regret having kept him on board the ship.

Almost immediately after taking over Waring, the prize crew cut up the American flag in order to make a Rebel banner.

This action “incensed me to use violence,” Tillman later recalled, for it “made my blood boil, and I vowed to have revenge.”

For about a week, Waring cruised on the high seas while, unbeknownst to its Confederate captors, Tillman and Billy Stedding, the German, were plotting a way to secure their freedom.

“In the afternoon we talked it over again, and I said it’s our only chance, and if we don’t go in tonight and clear ourselves we have to go to a southern port; go into slavery, or have our heads chopped off,” Tillman later stated.

He spoke to McLeod about the plans, but the British sailor was not willing to join the mutiny.

That night Tillman and Stedding worked alone, preparing their weapons and finalizing their plans. Finally, Stedding came to Tillman and said, “Now’s our time.”

Shortly before midnight on July 16, Stedding signaled to Tillman that the prize crew was asleep. Stedding drew a pistol and clutched a knife while keeping watch on the deck.

Tillman grabbed a hatchet and crept into the captain’s quarters, where he “raised his axe and gave him a vigorous blow on his skull, from which he seemed to be launched into eternity, for he moved not an inch.”

By the time Tillman was finished, the captain’s stateroom looked like a slaughterhouse, with the bed linens and floors “covered with blood.”

Tillman next found the first mate sleeping nearby “and dealt with him in the same summary and terrible manner.”

McKinnon, the passenger, witnessed this second slaying and let out a scream in terror.

According to Tillman, “He jumped up very much affright. I said ‘you need not be scared; I suppose you know what I have been up to.’ He said ‘yes.’ I told him to take a chair and sit down. He did so.”

Before leaving, Tillman assured him, “Do you be still; I shall not hurt a hair of your head.”

Tillman went to the poop deck, where he saw Stedding holding a knife and pointing a pistol at the second mate, who had just been awakened by the sound of McKinnon’s scream.

Fearing that the report of a gunshot would awaken the other two members of the prize crew, Tillman signaled to Stedding not to fire.

Still groggy from sleep, the second mate said to Stedding, “What the h—ll is all this noise in the cabin.”

But before he could get to his feet, Tillman struck him with his hatchet near the temple. The second mate had been lying near the desecrated Union flag, and now it bore “several marks of the crimson fluid.”

Tillman and Stedding grabbed the second mate and threw him overboard. Then they went below-deck and grabbed the captain and first mate and flung them overboard, too.

The entire enterprise took less than eight minutes.

There were still two men from the prize crew asleep, one named Miller and the other named Dorset.

Tillman said to Stedding, “We’ve done all the butchering we shall on this voyage; the other two fellows I’ll take back; there are two of them and two of us; we can manage them I guess.”

Stedding took a knife away from Miller, and Stedding, Tillman and McKinnon then put the two prize crewmen in irons.

Dorset begged Stedding to spare his life. “Yes, we don’t intend to spill any more blood than we have done,” Stedding assured him.

Next Tillman called McLeod, the British sailor, out of his berth and said, “Do you know we have taken this vessel to-night?”

McLeod replied, “No.”

Tillman said, “You would not help to take this vessel, and I want to see if you will help to take her to a northern port. We saved ourselves so far.”

After McLeod agreed to work for the mutineers, Tillman hove the vessel on a northwest course.

The mutineers, however, did not know how to navigate the ship.

The next morning Tillman spoke to one of the prize crew, saying, “I want you to join us, and help take this vessel back. But mind, the least crook, or the least turn, and overboard you go with the rest.”

“Well,” replied the man, “I will do the best I can.”

Tillman recalled, “And he worked well all the way back. He couldn’t do otherwise. It was pump or sink.”

For more than four days the men worked with “unremitting vigilance and exertion” and brought the vessel to port at Sandy Hook, N.J., just south of New York City.

Once in New York, Tillman was placed in police custody as a witness, while the flag, hatchet, and Rebel captain’s coat were held at the headquarters of the harbor police.

People gazed in wonder at the hatchet.

“One would be surprised to look upon the small instrument which did such serviceable and at the same time bloody work on board the schooner,” marveled the New York Herald.

“It is a simple wood hatchet, the handle about eighteen inches in length and the head not weighing much over sixteen or eighteen ounces…being covered with the blood of those whom it slew, and several splinters knocked off the handle in the efforts of the brave Tillman to destroy the enemies of his flag.”

New Yorkers, eager for positive Union news to help offset the newly arriving news of the Federal defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, hailed Tillman as a hero.

The Herald stated that his “name will now become historic as the enactor of as great a piece of daring and heroism as perhaps the world ever saw” and that he “possesses the physique and general appearance of a brave man.”

The editors marveled “that he could bear almost anything than seeing the dear old flag which had fluttered so long over the freest country in the world transferred into the colors of the rebel government. His powers of speech, although tinctured with that accent peculiar to his race, yet possesses a simple eloquence and force of its own, which has been the remark of all who conversed with him yesterday.”

On July 22, Tillman was taken from the House of Detention to the office of U.S. Marshal Robert Murray, where he was visited by “a large number of citizens” of all classes.

They greeted him “with the warmest expressions of esteem and laudation for the manner in which he had taken from the robber bands of the rebels the property so ruthlessly stolen.”

At the marshal’s office Tillman held court as a line of visitors came to meet him. Sitting comfortably in an armchair, Tillman rose and bowed “with an air of humility” and shook the hand of each guest. The visitors praised him for his gallantry and bravery, telling him he deserved the “thanks of the whole country.”

“You deserve to have your liberty,” one caller told him.

“Yes,” said another, “If all the colored people were like you, we would not have all of this trouble.”

“I did the best I could,” Tillman replied. “I couldn’t see any other way to get my liberty.”

Tillman told another visitor that killing the men was “a good action” and a “service to that Union which I love.”

E. Delafield Smith, New York City’s federal prosecutor, joked, “We will have to run you for President yet.”

On one occasion, Marshal Murray asked Tillman, “Did they beg, any of them?”

Tillman replied, “They didn’t have any chance to beg.”

Tillman admitted that he had initially thought about trying to capture all five of his captors, but quickly determined that this would not be practicable.

“There were too many for that; there were five of them and only three of us. After this I said, well, I will get all I can back alive, and the rest I will kill.”

Tillman became something of a celebrity in New York City and throughout the nation.

One photographer advertised his photograph “for sale at wholesale,” while P.T. Barnum’s American Museum announced that he “will receive visitors at the Museum at all hours, and relate his experiences with Southern chivalry and exhibit the Secession Flag which the rebels made out of the schooner’s American Flag; also a Rebel Cutlass and THE IDENTICAL HATCHET with which Tillman killed the ocean robbers.”

William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator noted that one print depicted Tillman “as an embodiment of black action on the sea in contrast with some delinquent Federal officer as white inaction on land.”

It continued: “This one signal act of colored American executiveness, thus exhibited in shop windows and elsewhere to the masses, outweighs any amount of argument or rhetoric — for here is a palpable fact, directly appealing to their sense of justice, and invested, let us hope, with a potent and magical influence towards conquering that offspring of slavery, prejudice of color.”

On October 29, 1861, Tillman, Stedding, McLeod, and McKinnon sued in the federal court in New York City, claiming the value of the ship as salvage.

The owners of the vessel and cargo objected, asserting that Tillman could not claim a share of the salvage because he had been “animated by a desire to escape the doom of Slavery, to which he feared, not without reason that his captors intended to consign him.”

But a recent precedent led the local press to believe that the court would likely rule in favor of Tillman and “will make his ebony face to shine with joy.”

And that is precisely what happened. Tillman and Stedding offered gripping testimony before the court.

And in a remarkable decision, Judge William D. Shipman, a President James Buchanan appointee, awarded Tillman and the other plaintiffs a $17,000 judgment in the case.

Roughly half of that award went to Tillman, while Stedding received the next largest share.

The abolitionist editors of The Liberator noted the irony of Tillman’s legal victory in light of the 1857 Dred Scott decision — a case that held that African-Americans were not citizens and could not sue in federal court.

“It will be recollected that Tillman belongs to that class of persons who, according to Southern expounders of law, have no status in a United States Court, and no rights, either, which a white man is bound to respect.

Southern newspapers offered little reaction to the case, simply reporting the verdict without much commentary.

The editors of the New Orleans Times-Picayune took notice of Barnum’s advertisements for the public to come see Tillman, writing with derision, “This enables the public to see the greatest hero of this war!”

Larger, bloodier events quickly pushed the story of Tillman’s fight for freedom on the high seas out of the headlines, and he ended up being a footnote of Civil War history.

But in addition to making for a stirring tale of a man battling to stay free, the reception to Tillman’s story and his court case forced Confederates leaders to realize that they needed to maintain respectability among the powers of the world.

The civilized world had rejected both privateering and the trans-Atlantic slave trade over the previous five decades.

If the Confederacy wanted to gain international recognition, it could not permit its privateers to engage in a black market slave trade.

Epilogue: More Jeff Davis Drama

Jacob Garrick was another black sailor who escaped Jeff Davis.

Garrick was a 25-year-old native of the Danish West Indies, a free man who was serving as a cook on Enchantress, a merchant ship out of Boston, when it was captured by Jeff Davis on July 6, 1861.

William Smith, the prize master placed in command of Enchantress, planned to take the vessel back to Charleston, where he would sell Garrick into slavery for $1,500.

But on July 22, Garrick’s fortunes improved when the Union steamer Albatross came up next to Enchantress to check its cargo, as shown in the above illustration.

Garrick threw himself overboard, shouting that Enchantress was a “captured vessel of the privateer Jeff Davis and they are taking her into Charleston.”

Albatross picked up Garrick and then arrested Enchantress’ crew. Albatross towed Enchantress to Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads, Va., and then to Philadelphia, where William Smith found himself indicted for piracy.

Garrick testified against Smith during the trial, depicting him as a pirate and a slave trader.

One member of the prosecution called Smith’s actions “an offence without feeling, because to tear a man from his home and enslave him forever, against the usages of warfare, stamps this transaction…[as] a piratical, outrageous aggression, without any of the color or the forms of law.”

The trial ended on October 25, and Smith was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

Four days later, on October 29, all but one of the other crewmen were also found guilty.

Jefferson Davis, however, threatened to retaliate if Abraham Lincoln should carry out the execution.

Davis set aside 14 Union prisoners of war, including then-Col. Michael Corcoran of the 69th New York Volunteers, as hostages in the place of Smith and the other privateers.

Confederate authorities demanded of the Lincoln administration “an absolute, unconditional abandonment of the pretext that they are pirates” before an exchange would take place.

After protracted negotiations, the prisoner exchange finally took place in June 1862.

This article originally appeared in Civil War Times Magazine, one of Navy Times’ sister publications. Jonathan W. White is the author or editor of eight books, including Midnight in America: Darkness, Sleep, and Dreams During the Civil War (2017) and “Our Little Monitor”: The Greatest Invention of the Civil War (2018), with Anna Gibson Holloway. Check out his website here.