It's no secret that the Navy has 6,200 billets in deploying sea duty commands that aren't filled. What most don't know is how the Navy got here, why it happened and when it will be fixed.

“As has been pointed out, we have some manning challenges that we’re working through, right now,” Adm. Christopher Grady told lawmakers during a Feb. 26 hearing. “The number, specifically, is the 6,200 billets at sea that are not filled right now, although, the Navy, with your help, has purchased those billets and we will be flowing them into the fleet, over time.”

But Grady, who helms Norfolk-based Fleet Forces Command, knows it’s not a problem that can be instantly fixed because his Navy is faced with two simultaneous challenges — staffing a growing Navy while trying to plug holes in a fleet that routinely deploys overseas.

RELATED

For much of the past seven years, during an era of austerity for the armed forces, service leaders have been battling to fill 95 percent of billets on vessels heading off on deployment.

Critics, however, have voiced concerns that placing a person in a billet doesn’t mean that he or she has all the skills to do the job.

The Navy tracks another measurement — “fit” — that indicates sea duty billets and the percentage that are filled by sailors with the right rating, pay grade and training up to the skill levels necessary to competently execute the assigned mission.

The Navy wants the “fit” measurement to never dip below 92 percent.

Leaders also want to reach the 95 percent fill rate when a ship starts its maintenance phase and then keep it manned up through the training and deployment cycles, but that also doesn’t always occur.

"Sometimes we have to take some risk in the maintenance phase before we have all of the people on board," Grady told Congress. "But it is, I believe, both fleet standards that no one deploys without the full complement of people that they will have."

What Grady didn’t mention was that it’s actually getting gradually better.

Last year, the service recorded 6,850 at-sea gaps, 600 billets more than January’s deficit. But that’s still less than half the number of at-sea gaps in 2012.

RELATED

To understand this phenomenon requires a return to the darkest days of 2017.

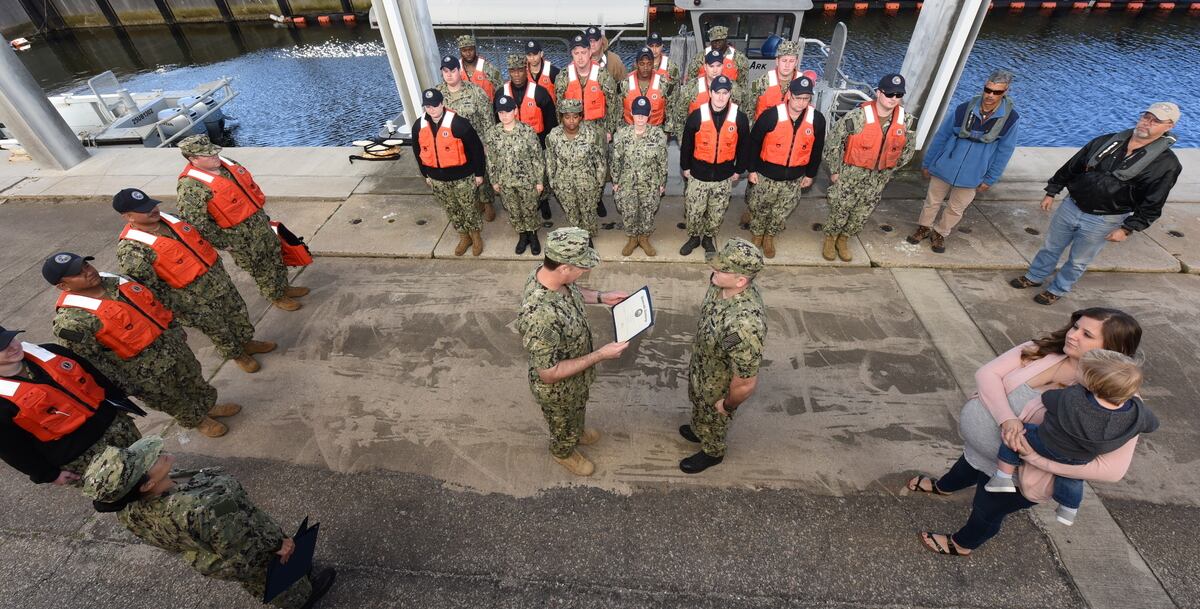

A key lesson that emerged from investigations into the deadly 2017 collisions in the Western Pacific involving the guided-missile destroyers John S. McCain and Fitzgerald and a pair of commercial vessels was that the warships were undermanned.

That was a problem that not only plagued the surface fleet but also aviation and submarine crews.

Years of manpower drawdowns, especially following 2011 “sequestration” budget cuts that put automatic funding caps on defense spending in order to divert a default on the federal government’s debt payments, took a toll.

But so did experiments with “optimal manning” plans that optimistically trimmed manpower flowing to the ships, based partly on assumptions about how technology could replace sailors.

In early 2012, the Navy tallied 11,495 gaps at sea.

The workhorse of the surface fleet, the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer, averaged a crew of 240 sailors, with only 92 percent of billets being filled.

When the Navy began wielding both voluntary and involuntary efforts to rightsize the fleet, the staffing problem initially got worse. Gaps jumped to more than 15,000 in early 2013.

By early 2017, the number of gapped billets had fallen to 4,583 — between 4 to 12 percent deficits because the demand for sailors at sea still outpaced the supply. And the demand was about to grow larger.

After the McCain and Fitzgerald disasters, the Navy launched studies to figure how many billets were needed at both sea and shore commands.

“The billet demand signal at sea is constantly being updated,” said Capt. Amy Derrick, spokeswoman for the chief of naval personnel. “Over the past year, Navy conducted a comprehensive review of operational afloat manpower planning factors both for time at sea and in-port.”

The study’s goal, in the wake of the collisions in 2017, was to “ensure that the manpower requirements for each class of ship accurately captures the true sailor workload.”

The result was is that the finish line has again moved further out, with manning across all platforms rising by another four to 14 percent.

Derrick said the service is “in the process of applying these updated factors across the Fleet and making associated billing funding adjustments.”

For the workhorse guided-missile destroyer, that means hiking manning by 14 percent, Derrick said. That would bring a crew of about 272 officers and sailors today to 318 in Fiscal Year 2023.

That also will add about 2,500 billets to the fleet.

Navy leaders expect the service to reach appropriate staffing levels by FY 2023.

“It is a moving target, so that 6,200 won’t come down rapidly, because we are increasing the requirement,” Navy Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran told reporters in Norfolk on March 7.

RELATED

To better retain sailors, the Navy has relaxed its high-year tenure program and made it less likely for personnel to be discharged quickly if they fail to meet fitness standards — even if they will be barred from reenlistment.

The service also continues to seek record accession and retention goals.

Moran said that fixing manpower issues is “never as fast as we would like it” and that “when you decide to add sailors, it takes about two years” to actually get them trained and to the fleet.

“By the end of calendar year ’19 and into ’20, we’ll get healthier every day,” he predicted.

To VCNO, forward-deployed ships will continue to get the manpower “right away,” which will mean a ready force abroad better “than it’s ever been on both fit and fill,” even if it will take longer to fill out the rest of the fleet.

“They’re not right at the level they should be,” Moran said. “So we still have work to do.”

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.