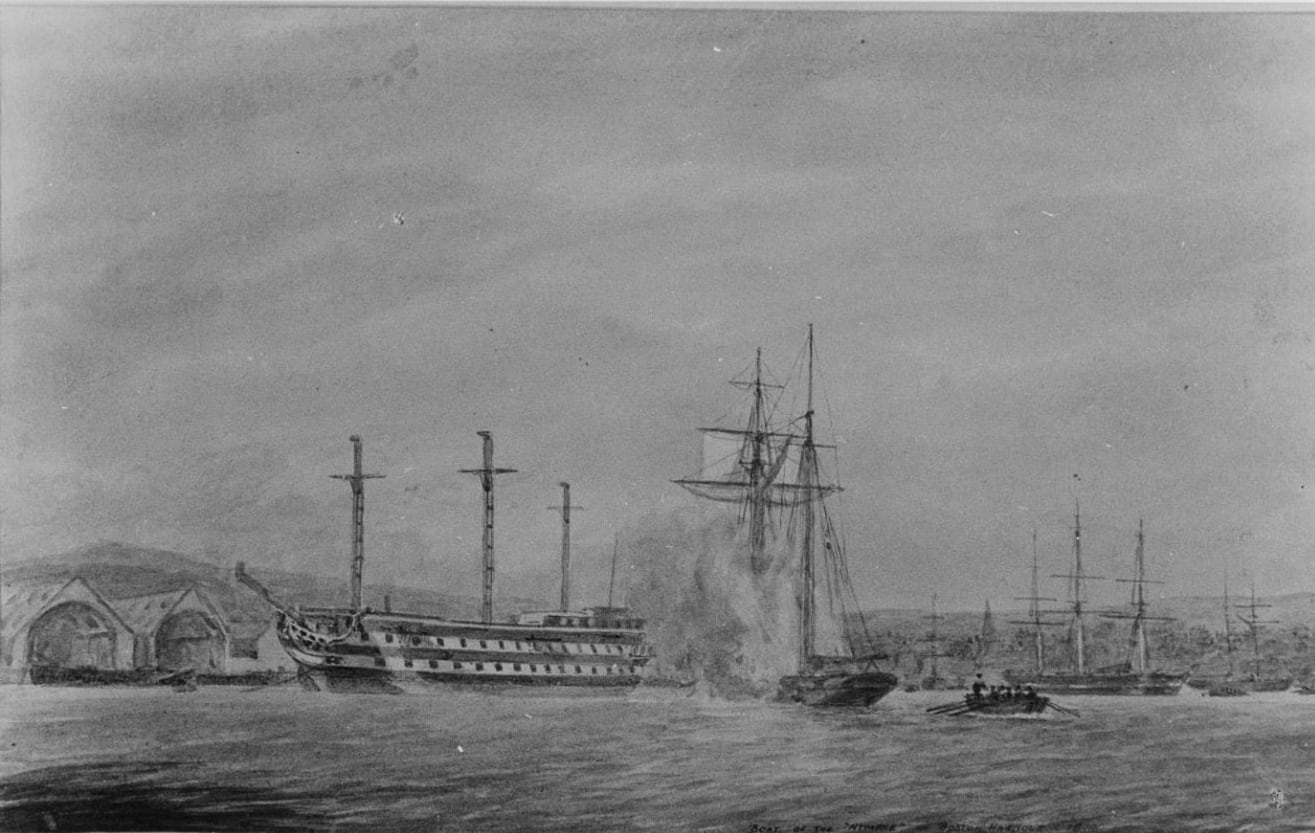

Fireships were vessels that, when filled with combustibles or explosives, could be floated or blown into enemy ships to disable or destroy them.

In the age of sail, fireships could wreak their flaming havoc with terrifying rapidity. They could also force an enemy fleet to break anchor or split its formation.

Although fireships date to ancient times, their use peaked between the late 16th and early 19th centuries in Europe, during which time their design and deployment became increasingly sophisticated.

A central fireroom, packed with flammable materials, provided the point of ignition; tin or wooden fire troughs — themselves filled with combustibles — quickly channeled the blaze throughout the ship, and fire barrels vented flames up to the sails and rigging.

Gunpowder charges in fire ports on each side of the hull would blow them open as the blaze took hold, ensuring a good flow of oxygen into the interior of the fireship.

If these components were properly configured, the fireship (typically up to fifth rate in size) would be engulfed by flames from stem to stern within five minutes of the quickmatch fuses being lit.

A skeleton crew would typically sail the fireship right up to an enemy vessel before igniting it.

Sally ports (exit doors) gave members of the crew a means of escape.

The ends of the fuses were typically located at these ports so the crew could light them and immediately flee in a small boat towed behind the fireship.

Fireships largely died out with the advent of steel warships and rifled cannons, though old ships packed with explosives have occasionally been used the same way.

Chris McNab is a military historian based in the United Kingdom. His most recent book is The Falklands War Operations Manual (Haynes Publishing, 2018). This article appears in the Spring 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History, a sister publication of Navy Times, with the headline: Weapons Check | The Fireship.