Following their Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese military forces swept through the western Pacific at a shocking pace.

Their strategic objective was to control the region from the Aleutian Islands south to Australia.

By early May 1942 they had already taken key military and strategic objectives, including Wake Island, Hong Kong, Singapore, Borneo, Sumatra, Timor, Bali, Java and the Philippines, as well as Rabaul on New Britain Island and Tulagi in the central Solomon Islands.

Australia lay within reach.

Realization that the United States would soon bring to bear its industrial might in the Pacific theater prompted particular urgency on the part of Japanese military planners.

Adding to that pressure, on May 3 carrier-based Japanese and Allied forces confronted one another in the Coral Sea, off Australia’s northeast coast.

It marked the first naval battle in which the crews of opposing ships were not within sight of each other and did not fire directly at one another.

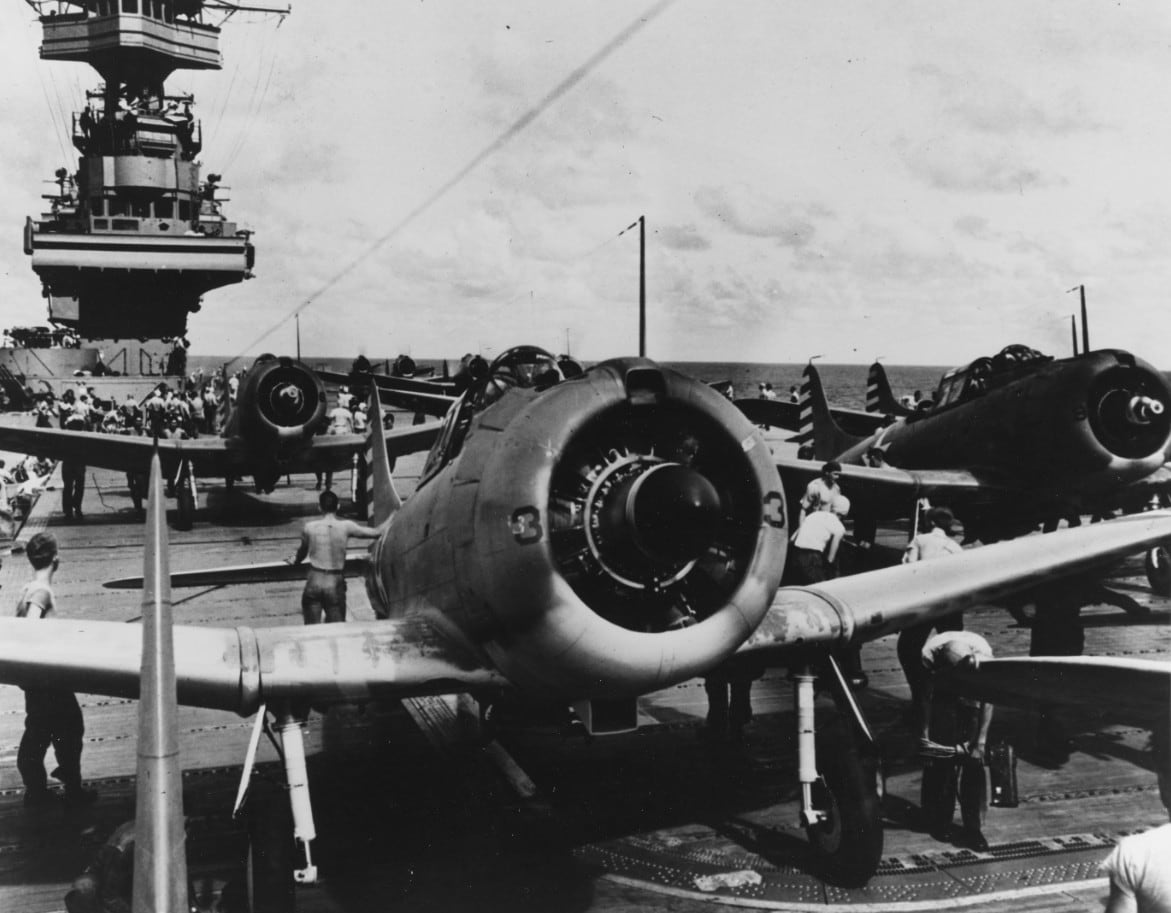

On May 7 Japanese aircraft sank the U.S. destroyer Sims and severely damaged the fleet oiler Neosho, while search aircraft from the carriers Yorktown and Lexington pinpointed the Japanese light carrier Shoho, which was covering an invasion group headed for Port Moresby, at the southeastern end of New Guinea.

Attack planes from the U.S. carriers quickly sank Shoho. Immortalizing the event was the terse radio message, “Scratch one flattop!” from Lt. Cmdr. Robert Dixon, who led Lexington’s dive-bomber squadron.

The sightings of Neosho and Shoho had created more than their share of confusion on both sides. Japanese scout pilots, for example, had misidentified Neosho as an aircraft carrier, convincing commanders they had located an important U.S. warship and prompting the launch of all available aircraft.

Meanwhile, a miscoded message from an American scout plane had reported the sighting of a Japanese screening force as a sighting of the main Japanese carrier force; as a result both U.S. carriers also launched all available aircraft.

Fortunately for the Allies, the strike aircraft from Yorktown and Lexington came upon Shoho, and its sinking proved more important than first appeared.

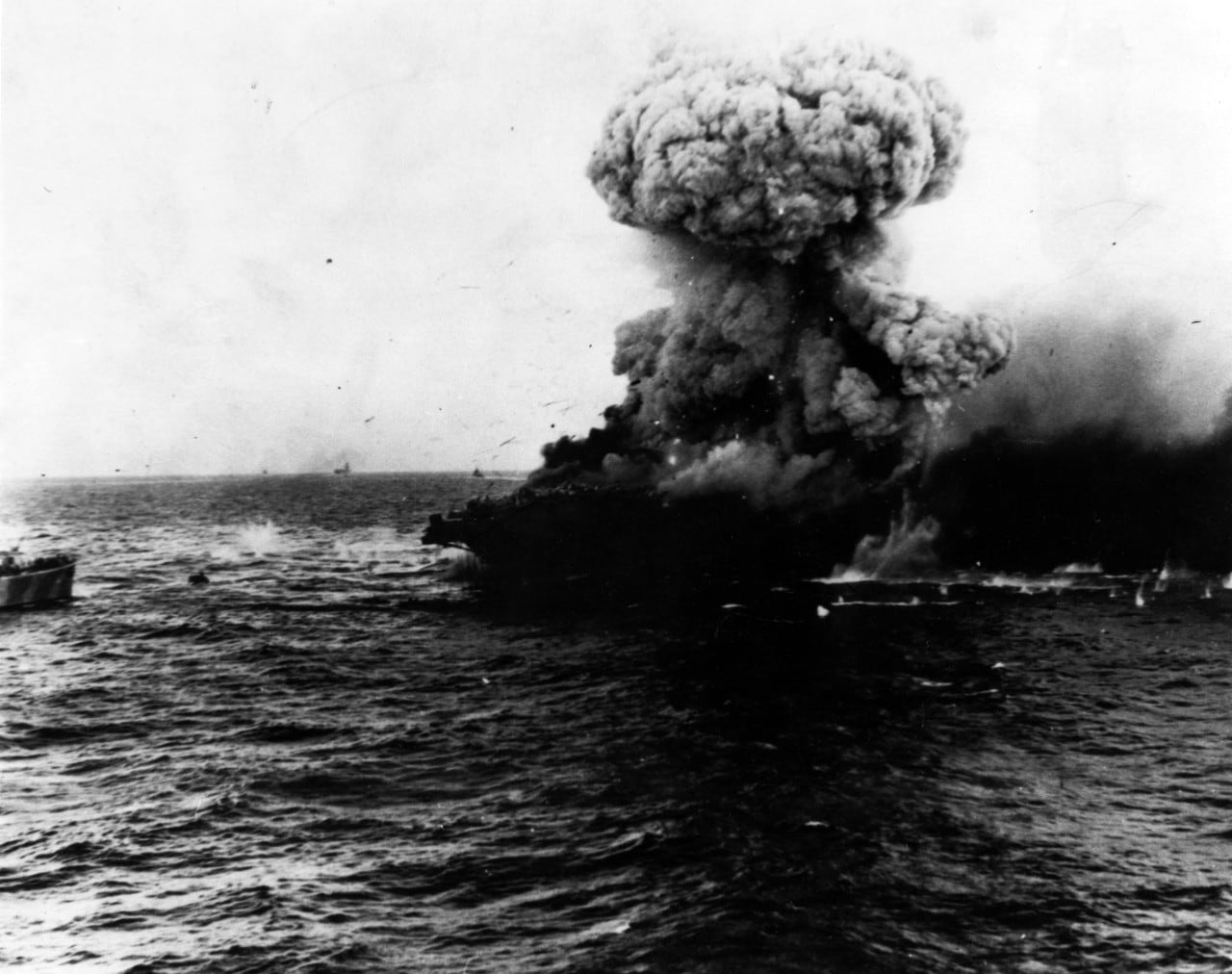

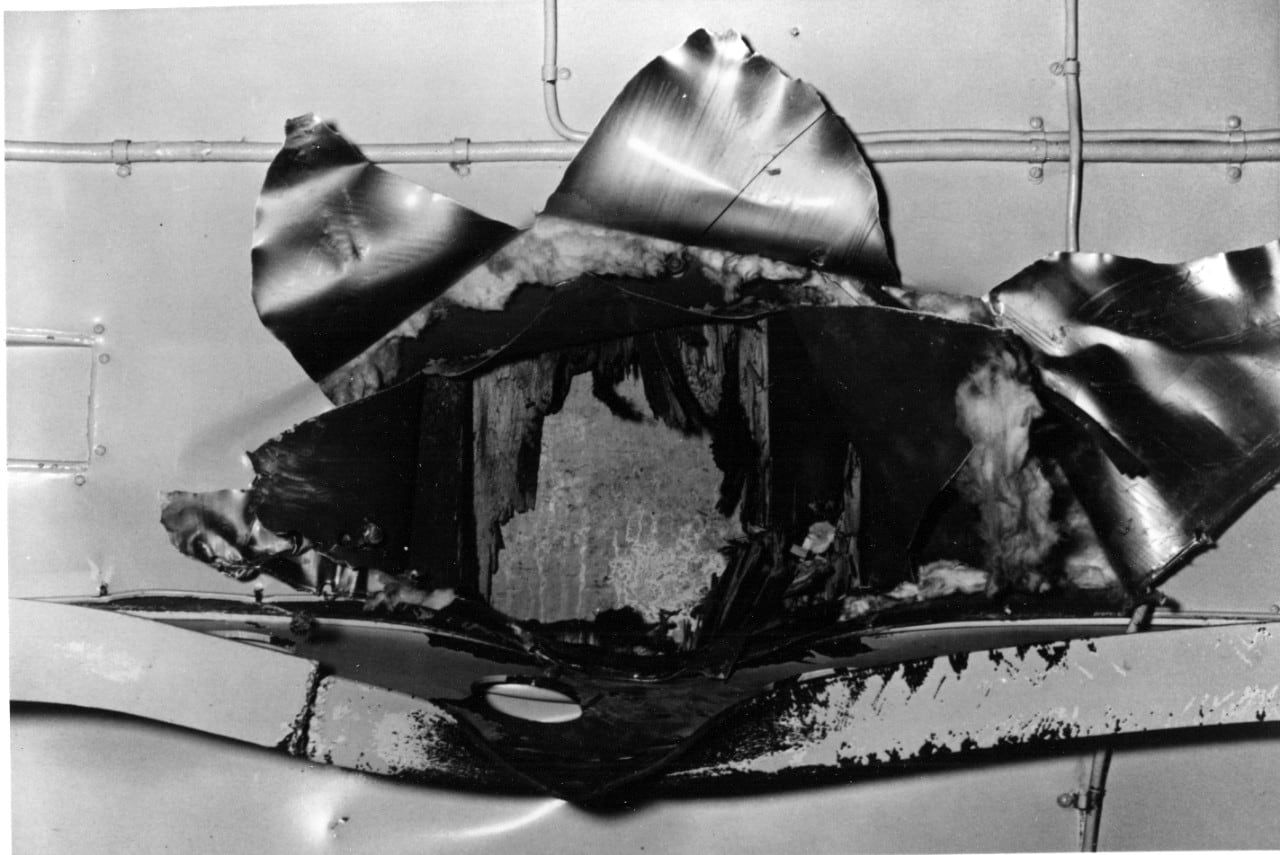

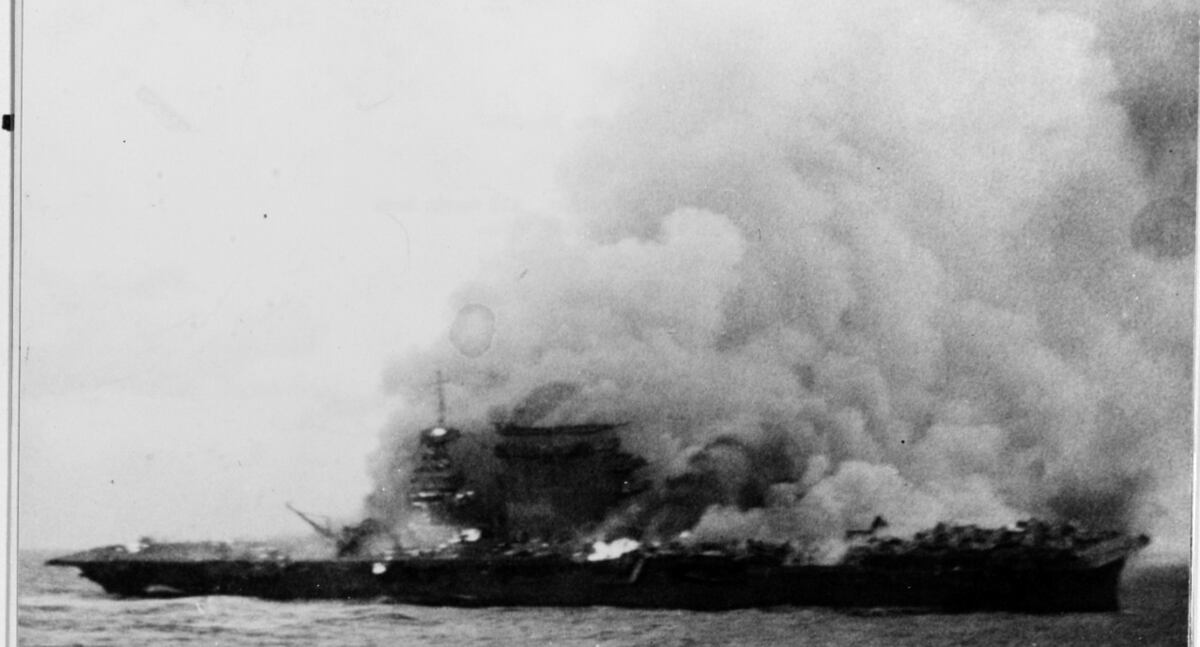

The climax of the naval battle came on May 8 as the opposing carrier strike forces directly engaged one another. U.S. aircraft severely damaged Shokaku, one of the two Japanese fleet carriers, while Japanese planes hit both Yorktown and Lexington, the latter of which later sank.

The Japanese had prevailed at the tactical level.

Strategically, however, the battle was a pivotal Allied victory.

Due to bomb damage and the loss of planes, neither Shokaku nor its sister carrier, Zuikaku, was available the next month for the Battle of Midway.

Yorktown, on the other hand, was repaired in time and played a critical role in that decisive U.S. victory.

Of greatest importance was the chance sinking of Shoho, which forced the Japanese to turn back the Port Moresby invasion force, marking the abrupt end of Japan’s southward race to achieve undisputed control of the western Pacific.

Lessons:

In geostrategic matters hubris is often a fatal character flaw.

Even industrial potential can shape military events.

In warfare the victory often goes to he who makes the fewest mistakes.

Luck is the wild card in combat.

Sometimes a tactical victory masks a decisive strategic loss.

The aircraft carrier henceforth supplanted the battleship as the centerpiece of major naval actions.

RELATED

This article originally appeared in the May 2014 issue of Military History, a sister publication of Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.