Adm. Chester W. Nimitz turned to his staff, blue eyes blazing, and said: “Remember this, we don’t know how badly [the enemy] is hurt. You can bet your boots he’s hurt, too!”

The Battle of the Coral Sea, the first significant clash between aircraft carrier forces in history, entered its climactic phase on the morning of May 8, 1942.

At 0820, Lt. j.g. Joseph G. Smith flew his Navy SBD Dauntless dive-bomber out of a towering cloud bank and caught his breath at the sudden sight of a dozen telltale ship wakes far below — the Japanese striking force.

Quickly he radioed the aircraft carrier Lexington: “Contact! Two enemy carriers, four heavy cruisers, many destroyers.”

Exactly two minutes later, and roughly 200 miles to the south, Imperial Japanese Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Kenzo Kanno banked his Nakajima 97 “Kate” torpedo plane and was exalted to discover a similar scene on the ocean surface.

“Have sighted the enemy carriers!” he reported to the fleet carrier Shokaku.

The opposing carrier forces had searched for each other in vain throughout the previous four days. Both sides had drawn blood the day before.

Now came the main event.

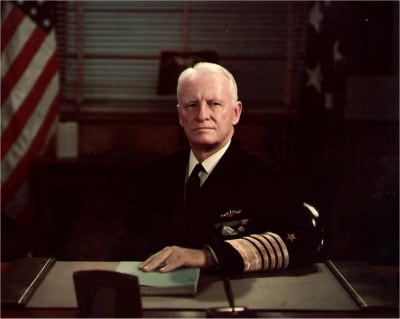

Thirty-five hundred miles away in Pearl Harbor, Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commanding the Pacific Fleet and the Pacific Ocean areas, stared at the sprawling map of the Coral Sea laid out on sawhorses in “Operations Plot,” his hillside command center, and waited uneasily for his task-force commander, Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, to break radio silence and report.

Nimitz likely took small consolation in the probability that his counterpart, Vice Adm. Shigeyoshi Inouye, commanding the Japanese Fourth Fleet from Rabaul, New Britain, was equally frustrated by the scarce information from the South Pacific.

The Battle of the Coral Sea would be Fletcher’s to win or lose, but Nimitz had an enormous stake in the outcome.

This would be his first major trial by fire as a fleet and theater commander. He was risking his precious carriers — all that remained of U.S. naval power in the Pacific — to thwart a new Japanese drive into the South Pacific, to protect the security of Australia, and to strike back against the seemingly invincible Imperial Japanese Navy.

Chester Nimitz had inherited what was left of the Pacific Fleet in a low-key ceremony on board the submarine Grayling in Pearl Harbor on the last day of 1941.

His tenure as chief of the Bureau of Navigation in Washington had ended two weeks earlier when President Franklin D. Roosevelt instructed Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to “tell Nimitz to get the hell out to Pearl Harbor and stay there until the war is won!”

During his epic campaign across the Pacific, Nimitz would eventually command more men, ships, and planes than any other military leader in history.

Yet the initial months of his command were a private hell. Short on resources because of the Allied strategy of “Europe first,” dangerously outgunned in any confrontation with the Japanese fleet, and limited to nuisance raids against small Japanese outposts, Nimitz endured the barbs of public opinion.

He became depressed and suffered from insomnia.

“I will be lucky to last six months,” he wrote his wife in March 1942. “The public may demand action and results faster than I can produce.”

Not the least of the problems Nimitz faced was a difficult relationship with his direct superior, Adm. Ernest J. King, commander in chief (COMINCH) of the U.S. Fleet. Abrasive and imperious, King had yet to appreciate Nimitz’s operational prowess.

Commander of the Atlantic Fleet during the prewar years when Nimitz had managed his powerful naval bureaucracy from Washington, King had a seaman’s scorn for the desk-bound.

Now the COMINCH wondered whether Nimitz would be bold enough to keep the Japanese off balance until he could convince his fellow Joint Chiefs of Staff to commit adequate resources to the Pacific.

Indeed, for the first several weeks of Fletcher’s deployment to the Coral Sea, King bypassed Nimitz and issued operational orders direct to the task force commander.

The commander in chief did not delegate command of Fletcher to Nimitz until mid-April 1942, barely three weeks before the battle.

King could be excused for his early suspicion of Nimitz.

Few people really knew the 56-year-old admiral from the Texas hill country. In fact, Nimitz’s relative anonymity begs the question of why Roosevelt and Knox entrusted him with the Pacific Fleet to begin with.

Nimitz’s performance since his graduation from the Naval Academy in 1905 had been steadfast but unremarkable. He spent much of his early years in submarines, then took a lengthy tangent into the obscure field of diesel engineering. He had never heard a shot fired in anger, never commanded a ship larger than a cruiser, and had never served on a joint tour in the War Plans office or in aviation.

A closer appraisal revealed that Chester Nimitz was resourceful, self-disciplined, and a consummate team player — invaluable attributes for the prosecution of the Pacific campaign.

Nimitz’s greatest strength, however, proved to be his ability to select excellent subordinates. These eventually included men who would become great fleet commanders, such as Raymond A. Spruance and William F. (“Bull”) Halsey, and other officers who played lesser roles equally well.

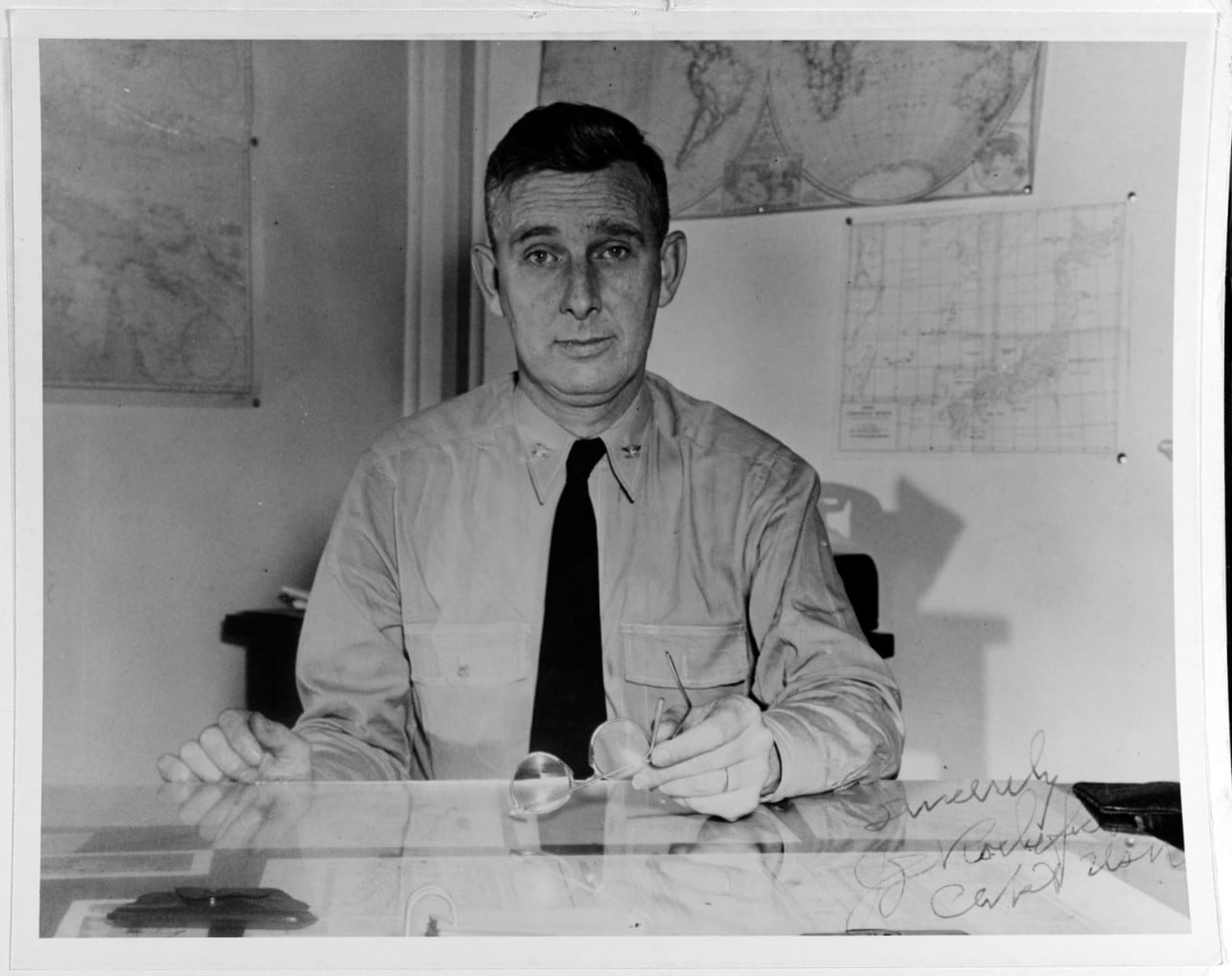

Soon after his appointment as Pacific Fleet commander, Nimitz retained Lt. Cmdr. Edwin Layton as fleet intelligence officer, along with Lt. Cmdr. Joseph Rochefort, who had been a Fourteenth Naval District cryptanalyst.

Both men had shared some of the blame for the Pearl Harbor debacle.

Nimitz knew Rochefort and his colleagues had in fact succeeded in breaking a portion of the Japanese naval code. He quickly realized that the commander could use partially decrypted messages, filling in the blanks where necessary.

This farsighted belief in Layton and Rochefort’s skills would win Nimitz limited success at Coral Sea, an overwhelming victory at Midway, and eventually the self-confidence to hold his own with Ernest King and his fellow theater commander, the outspoken Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Nimitz’s pink cheeks and grandfatherly manner disguised the soul of a warrior. He would soon prove to be an aggressive fleet commander, a daring gambler who combined an engineer’s logic with an abiding confidence in his subordinates.

A cautious commander trying to husband four precious carriers in the spring of 1942 would have cloistered his ships close to Hawaii.

Not Nimitz. He agreed (with reservations) to King’s preposterous scheme to send two carriers deep into the North Pacific to launch Jimmy Doolittle’s B-25 bombers on a one-way raid on Tokyo.

Meanwhile, Nimitz listened intently as Layton and Rochefort predicted a new Japanese offensive in the South Pacific. Based on this intelligence, he cajoled King to allow him to send Rear Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, commanding the Lexington task force then in Hawaiian waters, to reinforce Fletcher’s Yorktown force in the Coral Sea.

All four carriers would spend a perilous month very far from home waters.

Radio intelligence gave Nimitz an important edge. Rochefort told Nimitz that the Japanese would soon launch Operation MO in the South Pacific, to seize Tulagi in the Solomons and Port Moresby on the southeastern coast of New Guinea. If successful, these conquests would gravely threaten Australia.

Rochefort also convinced King of this peril, and the COMINCH reinforced Fletcher with a small Allied naval force commanded by Rear Adm. John G. Crace, Royal Navy, and approved Nimitz’s dispatch of Fitch with Lexington to the Coral Sea.

King then may have rued the timing of the Doolittle Raid. The navy’s most aggressive task force commander, Bull Halsey, was now approaching Japan with Enterprise and Hornet, nearly 10,000 miles from the Coral Sea, and King would have to rely on Fletcher.

He would have greatly preferred Halsey to Fletcher, whom he perceived as having lacked boldness in earlier South Pacific operations.

Nimitz, however, knew better. Fletcher, a year behind Nimitz at the Naval Academy, had recently served as his assistant at the Bureau of Navigation.

He had seen combat, and his actions at Veracruz, Mexico, in 1914 had earned him the Medal of Honor. Fletcher’s main weakness was his inexperience with carrier operations.

Nimitz, like King, would have preferred the experienced Halsey at his first major confrontation with the Japanese navy. But unlike King, he was comfortable with Frank Jack Fletcher.

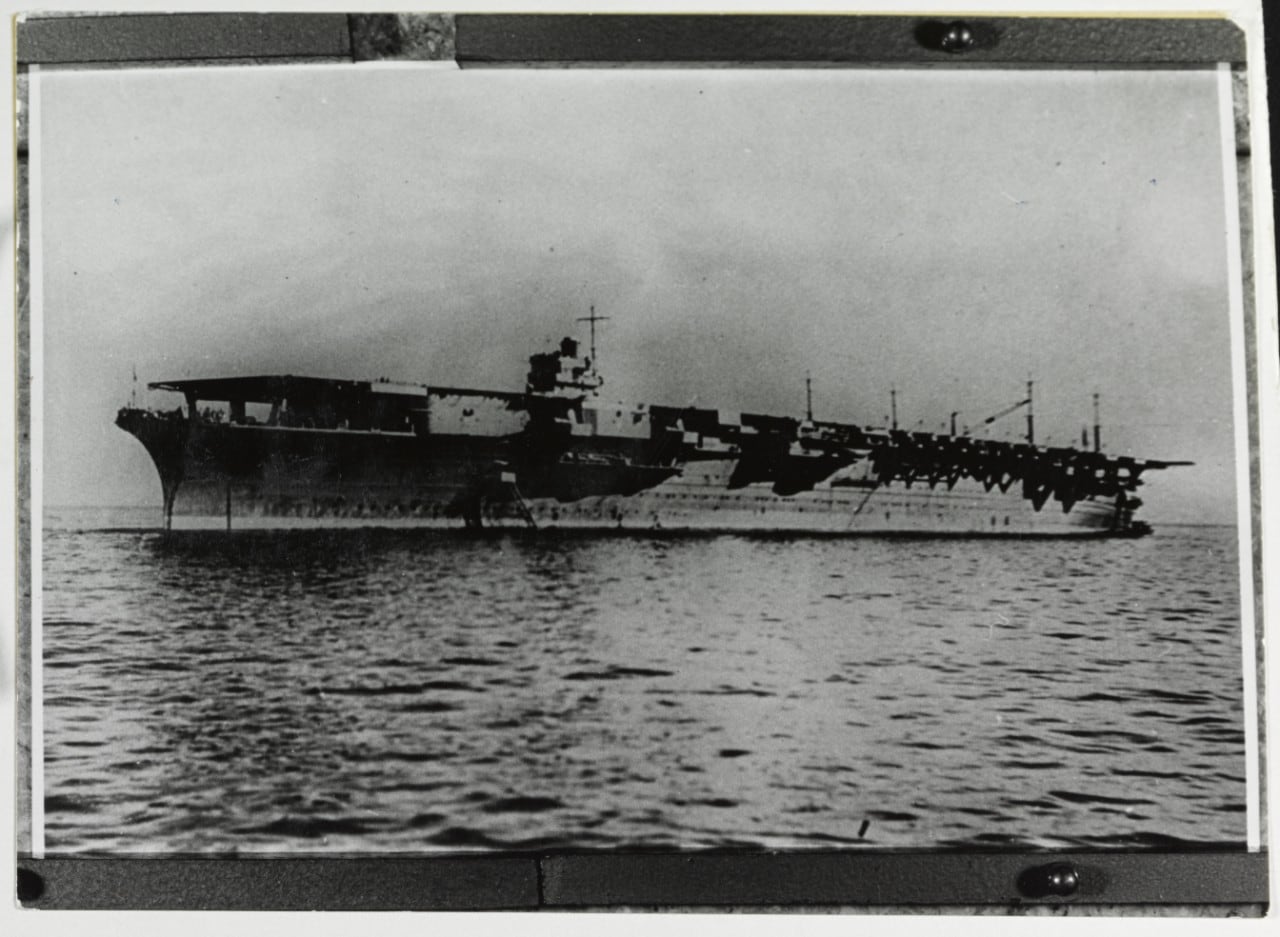

Nimitz realized from radio intercepts in late April that the Port Moresby invasion convoy, the “MO Force,” would be escorted by the light carrier Shoho and protected by Vice Adm. Takeo Takagi’s striking force, which included the large fleet carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku carrying more than 100 aircraft under Rear Adm. Chuichi Hara.

Being outnumbered three carriers to two did not particularly concern Nimitz.

Fletcher’s ships had radar; the Japanese did not. His radio-intelligence units on the carriers would augment the intercepts of other U.S. cryptographers. And he knew his pilots and deck crews were spoiling for a fight.

Still, since Pearl Harbor, Japanese naval aviators had ruled the Pacific skies in their impressive Mitsubishi Zero fighters, Aichi “Val” dive-bombers, and Kates. The MO Force assembled for the South Pacific assault was an experienced team.

Fletcher, Fitch, and Crace, however, would not join forces until the onset of the battle.

Historian John B. Lundstrom concluded that Nimitz had no intention of mustering a mere show-of-force presence in the Coral Sea, no simple deterrent to Japanese expansion. Instead, he sought a battle.

“We should be able to accept odds in battle, if necessary,” Nimitz told his staff.

The trick for Nimitz as theater commander was to provide maximum support to Fletcher without losing sight of a subsequent threat looming in the critical islands of New Caledonia, Samoa, and Fiji.

In the meantime, he would redirect Halsey to the Coral Sea as soon as he returned from the Doolittle raid, but Fletcher would have to intercept and defeat Takagi by himself.

On April 14, Nimitz ordered Fletcher to withdraw to Tongatabu, 500 miles south of Samoa, to recuperate and resupply for the coming fight, then return to the Coral Sea by the end of the month to rendezvous with Fitch.

Ten days later, Nimitz flew to San Francisco for a face-to-face meeting with King, the first of many such meetings during the war.

The surviving minutes of the meeting supply scant detail and were written in a cryptic manner. They indicate that the first topic discussed was the need “to suppress information gained through radio intelligence (substance and terminology),” while the second was Fletcher’s capability to lead a two-carrier task force with so much at stake.

The notes show that both men “expressed uneasiness…but decided to take no further action.”

Nimitz returned to Pearl Harbor, met with an exhausted Halsey, congratulated him on the sensational Doolittle raid, then ordered him to get under way to the Coral Sea.

There was no time to lose. Zuikaku and Shokaku had arrived at Truk on the 28th. The Australians were abandoning their outpost at Tulagi in advance of the Japanese sweep into the Solomons, and on May 3 the Japanese seized the small island.

Operation MO was underway.

Back in the Coral Sea from his respite at Tongatabu, Fletcher steamed south of the Solomons, waiting for some sign of the Japanese striking force.

Adm. Crace and his Allied force were expected by the fourth. Fitch and his Lexington force were on hand but still refueling, which was a slow, vulnerable process.

Fuel was a major factor.

After Fitch’s ships drained the replenishment oiler Tippecanoe, Fletcher had only the fleet oiler Neosho available.

Meanwhile, U.S. Army Air Forces B-25 bombers and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Catalinas continuously searched the vast sea.

Fletcher would rely heavily on these long-range, land-based searchers, but they served under MacArthur’s command, and inter-theater coordination suffered from inexperience and poor communications.

The Coral Sea is bounded on the north by the lower tip of New Guinea, the Louisiades, and the Solomons; on the east by New Caledonia and the New Hebrides; on the west by Australia’s northeast coast and the Great Barrier Reef; and on the south by latitude 25 degrees south.

In May, prevailing winds are out of the southeast, a factor that favored the Japanese carriers, which would be steaming into the wind as they rounded the Solomons, but would hinder the northwest-bound Fletcher.

Repeatedly he would have to reverse course to launch and recover aircraft, losing time and consuming fuel. Weather would play a critical role in the battle. Fletcher would benefit from sheltering storm clouds and a clear target during the preliminary encounters of May 4 and 7, but on the 8th, when the opposing carrier forces finally discovered each other, his luck would run out.

While Fletcher lacked Halsey’s impetuous aggressiveness, he had inspired, decisive moments.

When reports came from coast watchers and an RAAF Catalina that a Japanese amphibious task force had concentrated off Tulagi in the southern Solomons, he decided to strike immediately without waiting for the remainder of his force.

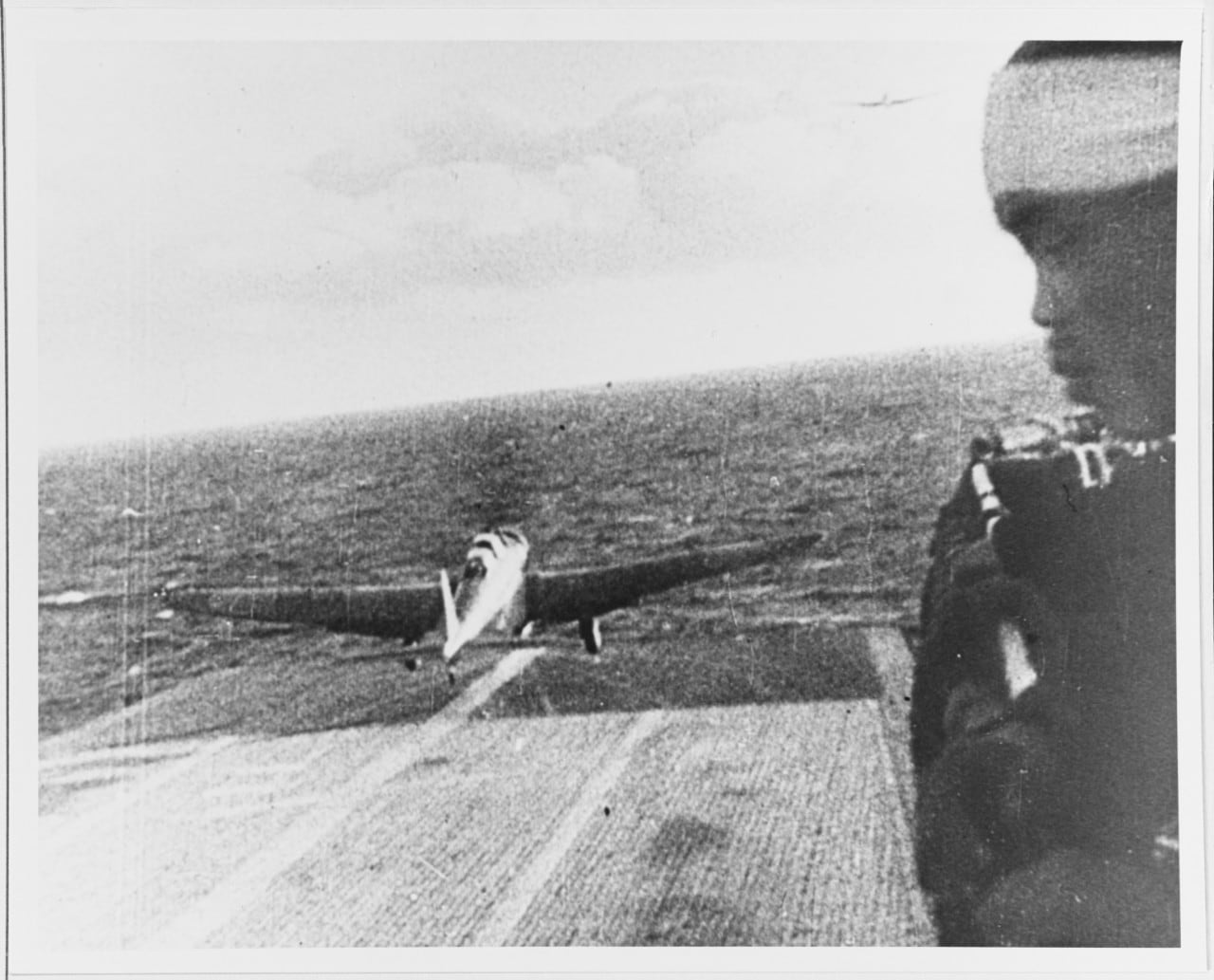

Taking advantage of the protective clouds, Fletcher launched three successive waves of Yorktown dive-bombers and torpedo planes, with separate fighter sweeps by F4F Wildcats. The planes passed over Guadalcanal and came out of the clouds over Sealark Channel, surprising the remnants of the Tulagi invasion force.

It should have been a turkey shoot. Adm. Takagi’s striking force was out of range, delayed by bad weather off Rabaul as he tried to ferry replacement aircraft ashore.

American pilots quickly shot down the few Tulagi-based seaplanes, but the inexperienced American fliers could not inflict significant damage on the Japanese destroyers and auxiliaries hastily getting underway from the anchorage.

Defective warheads and tactical errors rendered the torpedo planes ineffective. Dive-bomber pilots experienced an unwelcome fogging of their bomb sights during rapid descents. The aviators also misidentified Japanese ships and overestimated battle damage.

Despite their debriefing claim of having sunk a cruiser and several destroyers, the raiders actually achieved much less: one destroyer beached, several minesweepers and small commercial transports sunk.

The larger ships escaped.

And now Takagi knew an American carrier was operating in the Coral Sea.

“Some fun!” Fletcher reported to Nimitz.

“Congratulations and well done,” Nimitz replied, initially pleased.

Later, when the meager results of the Tulagi strike became known, he would characterize the operation as “disappointing in terms of ammunition expended to results obtained.”

Two extremely tense days passed. Zuikaku and Shokaku sailed into the Coral Sea. So did the MO invasion force, closely shepherded by Shoho.

Fletcher’s force finally completed its nerve-racking refueling. Fletcher dispatched Neosho and the destroyer Sims to a “safe” spot to the south.

Search planes from a dozen sources flew long orbits. It was a continuing deadly game of blindman’s bluff.

Nimitz found it difficult to remain stoical throughout the extended silence.

Sensing King’s impatience but lacking anything substantive to report, Nimitz sent a throwaway message the evening of the 6th: “From reports of enemy forces in the Louisiade area, believe Fletcher and Fitch should have been able to strike excellent objectives today, but have not heard from them.”

The next morning, a Japanese search plane reported sighting an Allied carrier and cruiser.

Adm. Hara quickly launched a massive airstrike from the two fleet carriers, but his searchers had critically misinformed him. His strike leader found no carriers, only Neosho and Sims.

The frustrated attackers struck the unprotected targets with a vengeance, sinking the destroyer and reducing Neosho to a smoking hulk that would drift with her survivors for the next four days.

Then Takagi received reports that the American carriers were now south of the Louisiades in a position where they were an immediate threat to the Port Moresby invasion convoy. Recovering and refueling his carrier aircraft would take too much time.

Instead, Takagi deferred the new mission of attacking the American carriers to shore-based naval bombers.

The Allied ships south of the Louisiades were not Fletcher’s carriers but the cruisers and destroyers of Crace’s force.

Fletcher had boldly divided his fleet, hoping that Crace would serve as the cork in the bottle should the Japanese invasion force escape the American carriers. This took some of the pressure off the carriers but placed Crace, lacking tactical air cover, at great risk.

At this point a Yorktown scout plane radioed a contact report of two Japanese carriers and four cruisers.

Fletcher acted decisively, launching 93 aircraft from both carriers, but his luck proved to be as snake-bit as that of his opponents.

Shortly after the huge formations had flown off in the direction of the sighting report, the reconnaissance plane landed on Yorktown and its pilot expressed amazement at being congratulated for finding the carriers. In fact, he had not. He had reported several smaller combatants, but his encryption code had been faulty, and now Fletcher had stripped both ships of their main armament.

Fletcher, greatly irritated, then received Neosho’s emergency report. While uncertain whether the ship’s attackers had been land- or carrier-based aircraft, Fletcher knew his fleet could not survive long in the Coral Sea without his last oiler.

Soon, however, he received a sighting report of a Japanese light carrier and escorts within 40 miles of the destination of his airstrike. Shaking his head in disbelief at these rapid shifts in fortune, Fletcher vectored his formation toward the new target of opportunity, near Misima Island.

The target was the light carrier Shoho, a converted submarine tender with half the displacement of Shokaku but still dangerous.

Aircraft from Cmdr. William B. Ault’s Lexington found Shoho first.

Ault led the attack, diving from 10,000 feet to drop a 500-pound bomb close to the wildly maneuvering ship.

“Torpedo Two’s” Lt. j.g. Leonard W. Thornhill had the distinction of launching the first successful hit against a Japanese capital ship, his torpedo detonating on Shoho’s starboard quarter.

Other torpedo planes and dive-bombers swarmed over the stricken ship, ignoring the cruisers and destroyers in the screen.

Shoho’s combat air patrol, led by Warrant Officer Shigemune Imamura in his Mitsubishi A6M Zero, tried to disrupt the attackers.

Imamura, a veteran of the China campaign, quickly shot down Lt. Edward Allen’s SBD Dauntless.

The F4F Wildcats entered the fray. They lacked the Zero’s agility, but their pilots were able to use the fighters’ diving speed to corner Imamura.

Lt. j.g. Haas shot him down a few hundred feet over the water, becoming the first navy pilot to down a Zero in the war.

There was no respite for the dying Shoho.

Yorktown’s air group soon arrived to apply the coup de grâce. Staggered by 13 bomb hits and 7 torpedo strikes, the carrier sank at 11:35 a.m., drowning more than 600 members of her crew.

Homeward bound, Lt. Cmdr. Robert E. Dixon, commanding Lexington’s “Scouting Two,” sent his classic report to the task force: “Scratch one flat top!”

Sinking the first Japanese carrier of the war was a remarkable psychological victory for the Americans, but in the process they had squandered the opportunity to sink a half dozen other combatants while they enjoyed nearly total air superiority.

“We had an overkill on the carrier,” said Lt. Cmdr. Paul D. Stroop, flag tactical officer to Adm. Fitch on Lexington. “But this being our first battle of any kind, why, everybody went after the big prize.”

Meanwhile, Adm. Crace’s Allied force guarding the Jomard Passage endured swarms of attacks from land-based enemy bombers and “friendly fire” from MacArthur’s B-17s.

The Japanese claimed they had sunk a battleship and a cruiser, but Crace’s superior seamanship brought his force through the ordeal unscathed.

The results of the day evidently unnerved Adm. Inouye, still in Rabaul. He had lost a light carrier, the Allies continued to block the invasion route to Port Moresby at the Jomard Passage, and the American carriers remained hidden in fog banks.

He ordered the MO Force to reverse course until Takagi could gain air supremacy in the Coral Sea.

Fletcher, immensely relieved to recover his aircraft before the Japanese could attack, was pleased at the sinking of the light carrier but concerned with the loss of the oiler Neosho. He was now a very long way from the nearest source of fuel.

He reported to Nimitz that the oiler’s loss “will cripple my offensive action and may cause my withdrawal in a few days.”

Nimitz ordered his staff to search for alternate fuel sources.

Takagi and Hara, embarrassed by the loss of Shoho and their inability to find Fletcher’s carriers, gambled on mounting a twilight airstrike using their most experienced pilots and led by combat veteran Lt. Cmdr. Kakuichi Takahashi.

The mission, flown on May 7, was a disaster.

Takahashi’s raiders, flying blind, flew past the American task force. Fletcher’s radar picked them up, and his fighter director vectored the combat air patrol for a surprise intercept. In the melee the Japanese lost nine aircraft against two American losses.

To the further chagrin of Takagi and Hara, Takahashi’s survivors jettisoned their torpedoes and bombs for the dogfight, then flew directly over the elusive American carrier force en route back to their own ships.

Takahashi’s report as to the whereabouts of Fletcher’s ships gave Takagi his only good news of that very long day. Finally, he knew the general location of his enemy.

Fletcher still did not have this luxury. Consequently, on May 8 he dispatched 18 SBD scouts in a 360-degree dawn search.

Takagi sent out only seven aircraft.

Yet both fleets hit pay dirt almost simultaneously.

Fifteen minutes after Petty Officer Kanno’s sighting report to Zuikaku, Fletcher received a radio intercept report that his formation was being “snooped” by an enemy carrier plane. Both task forces were now steaming toward each other at high speed, the range closing rapidly.

Fletcher signaled Aubrey Fitch to take tactical command, astutely bowing to Fitch’s dozen years’ experience as a senior aviator.

Fletcher was learning. In his first expedition commanding a carrier task force — the abortive Wake Island relief mission — he had retained his flag in the cruiser Astoria, foregoing the more necessary location on board Yorktown. Now Yorktown flew his flag, and Fitch, his academy classmate, would direct the day’s complex aerial battles.

The weather now turned against Fletcher and Fitch. Enormous cloud banks and rain squalls would protect the MO striking force this day, while Fletcher’s ships would be bathed in sunlight with an unlimited ceiling.

Fitch launched 75 aircraft from the two carriers beginning at 0900. Ten minutes later Hara launched 69 aircraft from Zuikaku and Shokaku.

Aided by tail winds, the Yorktown Air Group reached their target first. The Dauntless dive-bombers hovered in the clouds, watching the big enemy carriers cross an open space below, impatiently waiting for their slower TBD torpedo bombers to catch up.

By the time the TBDs arrived, Zuikaku was disappearing into a fog bank.

The dive-bombers began their assault on Shokaku at 1057. Right away it became evident that this was going to be a much tougher mission than sinking the hapless Shoho the day before.

Among the Japanese fighter pilots protecting the carriers was Petty Officer 1st Class Tetsuzo Iwamoto, the Japanese Imperial Navy’s leading ace with 14 kills from the China campaign, who would survive the war with 80 kills.

Iwamoto would not improve his score that day, but he and his wingmen riddled and disrupted the American attackers.

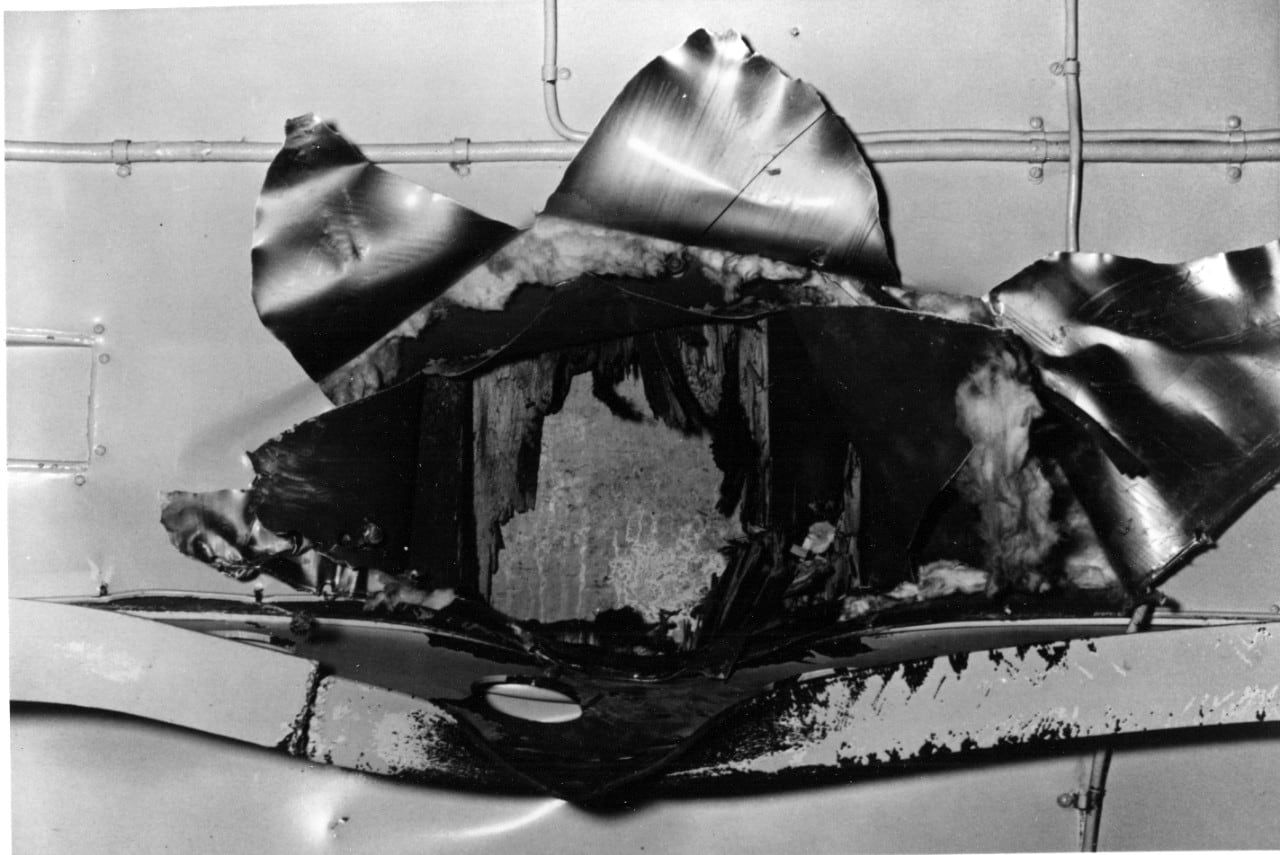

The TBD Devastators achieved no torpedo hits on Shokaku, but the Dauntless dive-bombers did register three hits despite their fogged-up bomb sights and Petty Officer Iwamoto’s slashing attacks from the flanks.

Lt. John J. “Jo Jo” White delivered the most crippling blow, a 1,000-pound bomb that set the flight deck ablaze before he crashed into the sea.

Lexington’s Bill Ault also claimed a 1,000-pound bomb hit on the flaming carrier, although he, too, would not return from this mission.

When Zuikaku steamed unscathed out of her protective fog bank, Adm. Hara groaned at the sight of the crippled Shokaku. Smoke engulfed the exposed carrier. She had suffered more than 200 casualties and could no longer launch aircraft.

Payback time came soon for the Japanese.

Petty Officer Kanno had loitered near Task Force 17 since his initial spotting report. Now, his fuel tanks nearly empty, he led Cmdr. Takanishi’s combined formations toward the American carriers.

At 1140, Lt. Cmdr. Stroop made his final entry in the flag diary on Lexington: “Under attack by enemy aircraft.”

Fitch’s radar gave him plenty of warning, but his fighter-direction officer had arrayed the combat air patrols out of position in range and altitude. Adjusting their vectors took valuable time. Soon the Japanese had obtained their preferred attack positions, upwind and up-sun.

Lt. Cmdr. Shigekazu Shimazaki, a veteran of the Pearl Harbor attack, led the torpedo-plane strike. Stroop watched their approach from Lexington’s flag bridge, later describing it as “a fine, nicely coordinated attack.”

Capt. Frederick C. Sherman maneuvered the carrier through a series of violent twists and turns to dodge the initial torpedoes, but more were on the way. Task Force 17’s antiaircraft gunners blazed away desperately, and Shimazaki would later admit, “Never in all my years have I imagined a battle like that.”

Fitch had insufficient Wildcats to cover all sectors and had to throw his scrappy Dauntless dive-bombers into the fray. The Dauntless pilots downed several Kates but fared poorly against the escorting Zeros. Four went down.

The Wildcats fought furiously.

Shimazaki reported: “Our Zeros and enemy Wildcats spun, dove, and climbed in the midst of our formation. Burning and shattered planes of both sides plunged from the skies.”

The air-to-air action was sustained and violent.

Veteran strike leader Cmdr. Takahashi would not return from this fight.

When Lt. j.g. Duran Mattson landed his Wildcat after this action his crew found the Grumman fighter riddled with 21 shell holes from 20mm cannon fire and countless machine-gun bullet holes.

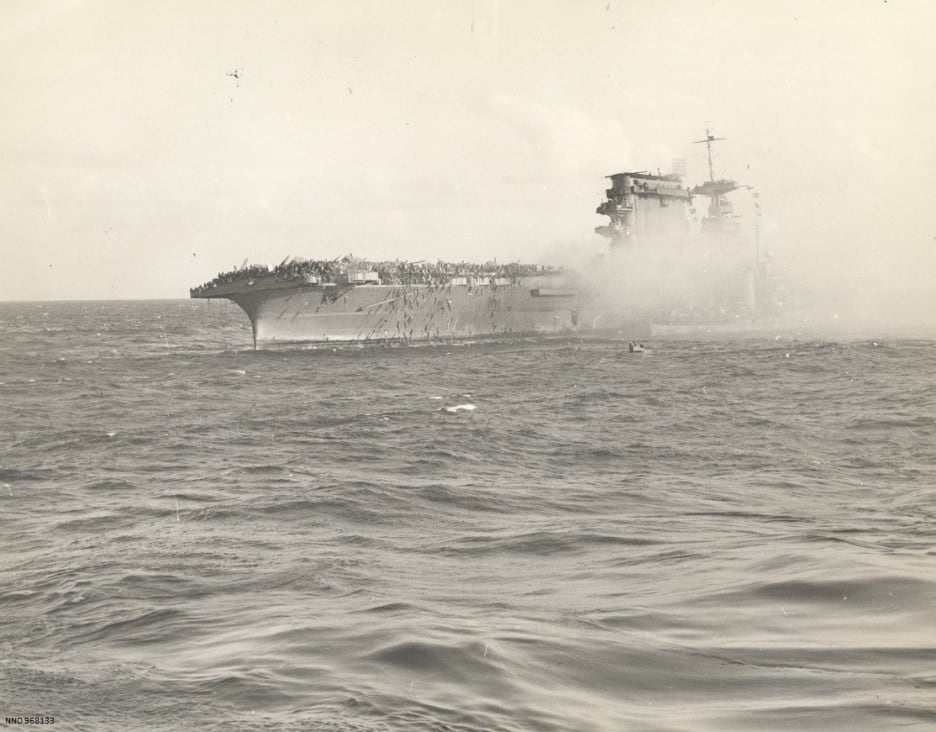

“Lady Lex” was doomed, despite these heroics.

Hammered by two torpedoes and two bombs, the giant carrier shuddered and slowed, burning fiercely.

The Japanese also hit Yorktown with a bomb that penetrated four decks and set her afire.

The Imperial Japanese Navy aviators returned to their ships, joyfully reporting to Hara that they had sunk both enemy carriers and avenged the loss of Shoho.

Yet Yorktown’s crew quenched her fire and kept her fully operational, and for a brief period even Lexington gave hope that she could limp to a port for repairs.

Then a deadly explosion wracked Lady Lex.

Aviation gas vapors had found a sparking motor in the internal communications generator room. Other violent explosions followed.

At 1630 Sherman had to secure his engineering department. The great ship went dead in the water, no longer able to launch planes.

As the fires approached the torpedo warhead magazine, Adm. Fitch spoke kindly to Sherman, “Well, Ted, I think it’s time to get the men off.”

Sherman gave the order to abandon ship, which was done with commendable discipline. More than 92 percent of the ship’s crew survived the day. Sherman was the last to leave the ship.

The destroyer Phelps then finished her with five torpedoes at 7:52 p.m., and Lexington went down.

Said Lt. Cmdr. Stroop, who had stuffed the day’s flag dispatches into his pocket before clambering down a rope into the water, “We felt very badly about the whole business.”

The first battle reports Nimitz heard came from intercepted Japanese radio messages claiming the destruction of both American carriers. Shortly after noon Fletcher advised Nimitz that he had heavily damaged an enemy carrier while sustaining some damage himself — on balance, good news.

The CINCPAC (Commander in Chief Pacific Area Command) “Graybook” command summary received the entry, “This was a red-letter day for our forces operating in the Coral Sea.”

Nimitz sent a decidedly premature message to Fletcher, congratulating him on his “glorious accomplishments.”

Fletcher’s subsequent report of Lexington’s loss shocked Nimitz. A staff officer observed that the news “was a terrible blow to Nimitz; he was visibly jolted and muttered several times that they should have saved her.”

Shaking it off, the admiral turned to his staff, blue eyes blazing, and said: “Remember this, we don’t know how badly [the enemy] is hurt. You can bet your boots he’s hurt, too!”

Nimitz then ordered Fletcher to retire from the scene, not willing to risk the damaged Yorktown in another battle against the undamaged Zuikaku.

Fletcher did not protest. Thirty-six aircraft went down with Lexington, leaving Fletcher’s task force with 39 operational planes.

Fitch had reported the threat of a third enemy carrier in the vicinity (a double sighting of Zuikaku, as it turned out), and Fletcher worried about his growing shortage of fuel.

Almost simultaneously Adm. Inouye canceled the Port Moresby invasion and directed Takagi to retire.

Shokaku would require months of repairs in a Japanese shipyard, and Zuikaku had suffered severe aircraft losses. (Ironically, Hara, like Fitch, was down to 39 planes.)

Neither carrier would be able to accompany the forthcoming Midway invasion forces, reducing by one-third the number of these key assets available for Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto’s complex battle plan.

Yamamoto, furious, ordered Inouye to return his surviving carrier to the Coral Sea to finish off the brash Americans. Takagi reversed his course sluggishly, pausing to refuel, but Fletcher was gone by the time he returned.

Even the survivors of Neosho had been rescued just before that hulk finally went under.

Takagi then set course for home, not realizing that the Japanese navy had unwittingly forfeited the Coral Sea to the Allies for the duration of the war.

Adm. King was also furious.

He had never forgiven Fletcher for his apparent timidity, and now he had suffered the loss of the Lexington, a ship King had once commanded.

He sent a peevish message to Nimitz demanding to know why Fletcher had failed to use his destroyers in a night attack against the Japanese carriers. Fletcher’s answer probably did little to assuage King, but he expressed his concerns over low fuel, the uncertain location of the enemy, the need to protect his own force, and the fact that all ships were crowded with Lexington survivors on the night of the 8th.

“Acting on my best judgment on the spot, no opportunity could be found,” Fletcher concluded.

Nimitz had greater concerns.

Joe Rochefort had convinced him that Yamamoto would surely head for Midway with an enormous naval force in a matter of two to three weeks. He had just lost one carrier, and the other three were thousands of miles out of position.

In a flash of brilliance, Nimitz ordered Halsey “to be seen” by Japanese patrol planes in the South Pacific.

This worked. Yamamoto, who already believed the claims of Hara’s aviators that both of Fletcher’s carriers had been sunk in the Coral Sea, now believed that the last two American carriers would not be a factor in his Midway campaign.

Meanwhile, both Emperor Hirohito and Adolf Hitler congratulated the Japanese “victors” of the Coral Sea.

But Nimitz nursed all three carriers to Pearl, ordered Yorktown repaired in three days, and sortied them under Fletcher and Raymond Spruance (who replaced an ill Halsey) just in time for Midway, one of the most decisive battles in American history.

Few people realized how much the obscure preliminary battle in the Coral Sea contributed to the Midway victory.

Coral Sea had been a tactical defeat — sinking Shoho could not offset the tragic loss of Lexington — but it proved to be a significant strategic victory.

The proposed seaborne assault on Port Moresby never materialized, nor did Japanese expansion into New Caledonia, Samoa, or Fiji.

The vital sea lines of communications to Australia had been preserved.

The Battle of the Coral Sea produced other benefits of great value to the Pacific Fleet.

It was, according to John Lundstrom, “the first acid test of naval carrier doctrine.”

Naval aviators gained much confidence from their first close encounters with Japanese Zeros. Eighteen months later, equipped with new carriers and amphibious forces, naval aviation would lead the sweep across the Pacific to the Japanese Home Islands.

As for Fletcher, Nimitz counseled his controversial task-force commander face to face.

Afterward, Nimitz wrote King: “Fletcher did a fine job…. He is an excellent, seagoing, fighting naval officer and I wish to retain him as a task force commander.”

Nimitz had made mistakes of his own in this campaign, but he was growing in experience and confidence.

He made masterful use of radio intelligence. He had learned to bite his tongue and not pester his commanders engaged in combat. To the extent that anyone could, he shielded Fletcher from King. And he was developing the essential perspective of a theater commander — keeping at least one eye on the next, more threatening operation.

These lessons would serve Nimitz well, not only at Midway, but also at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

RELATED

Joseph H. Alexander served in the Marine Corps for 28 years, including two combat tours in Vietnam. This article originally appeared on Jan. 21, 2010 in Military History Quarterly, a sister publication of Navy Times.