Radioman 2nd Class Mike Hannon walked to work with a palpable sense of unease on the morning of May 23, 1968.

As a communications specialist at Submarine Force Atlantic Headquarters, he was responsible for processing dozens of messages each day from submarines at sea, ranging from routine announcements to top-secret operational dispatches.

But hours earlier, when his eight-hour shift had ended at midnight, Hannon feared that one of the submarines on his watch might be in trouble — or worse.

The Norfolk-based Scorpion, one of the Atlantic Fleet’s 19 nuclear attack submarines, had been scheduled to transmit a four-word “Check Report”— encrypted to prevent the Soviets from intercepting it — that meant, in essence, “Situation normal, proceeding as planned.”

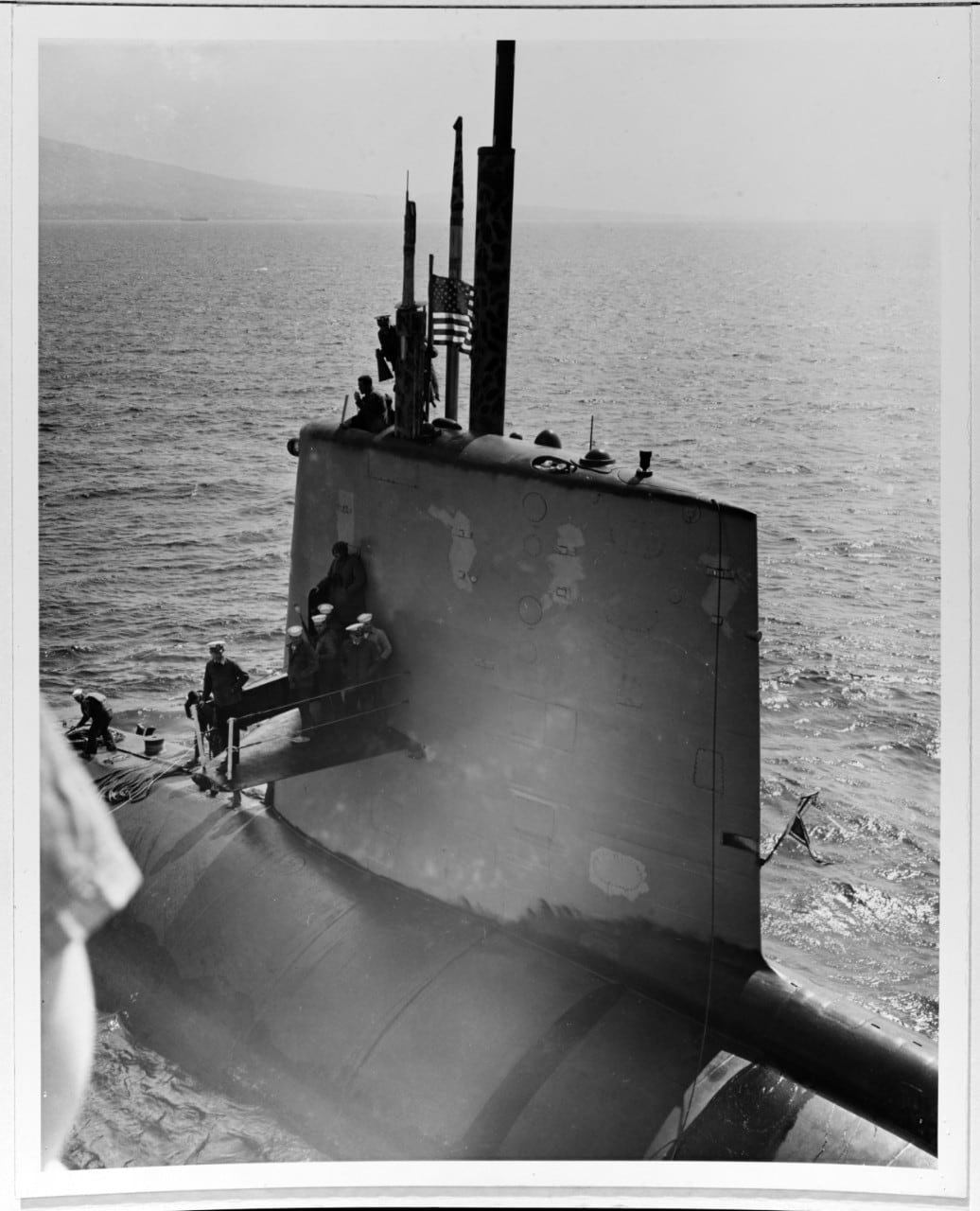

In this instance, the Skipjack-class submarine was returning to Norfolk after a three-month deployment to the Mediterranean Sea. Its standing orders called for a burst transmission every 24 hours that, when decrypted, read: “Check 24. Submarine Scorpion.”

But the previous day no message had come clattering out of the secure teletypewriter that Hannon used.

As he prepared to leave for the night, Hannon had briefed Radioman 2nd Class Ken Larbes, the petty officer coming on duty, about the overdue message. He then tapped on his supervisor’s office door and asked whether any late word had come in from the Scorpion.

Warrant Officer John A. Walker Jr. silently shook his head no. Was this the first hint of an emergency, Hannon wondered, or merely a delayed transmission caused by mechanical problems or stormy weather conditions?

Assigned to the message center at Submarine Force Atlantic (COMSUBLANT) headquarters in Norfolk, Hannon and a handful of other young sailors were responsible for processing all incoming and outgoing messages for submarines then operating with the Atlantic Fleet.

They worked in a large room full of top-secret encryption machines that took clear-text messages, scrambled them into impenetrable gibberish, and then dispatched the blocks of seemingly random text in Morse code via high-frequency radio to submarines at sea.

The radiomen reversed the process for incoming messages, taking encrypted transmissions from the submarines and “breaking” them back into clear text by using the same encryption gear.

“All messages, incoming or outgoing, were routed through my desk,” Hannon recalled years later. “Nothing came in or went out that didn’t go through that desk.”

During the five-minute walk from his barracks to the COMSUBLANT message center that Thursday, May 23, Hannon was unsure what he would find. As usual, he thought about the abrupt change in atmosphere he and his coworkers encountered each time they went on duty.

Walking up to the unassuming brick building, they would show their ID cards to the armed Marine guards, then step up to the door at the ground-floor entrance to punch in the code to release the cipher lock. Inside, they would take the stairway up to the second-floor message center.

Manned around-the-clock seven days a week, Hannon’s workspace was the solitary link between the three-star admiral commanding the Submarine Force Atlantic and the scores of nuclear- and diesel-electric-powered submarines that, on any given day, were engaged in operations ranging from routine training to top-secret reconnaissance missions at the edge of — and often inside — Soviet territorial waters.

Six to eight junior officers and radiomen typically tended various encryption machines under the supervision of a warrant officer ensconced in an office separated from the main work area by glass windows. On one wall, a large board tracked the current operational status of each of the 104 submarines assigned to Submarine Force Atlantic.

Despite the hushed ambiance, the message center was the nerve center of the U.S. Navy’s submarine operations during the Cold War.

“These regular radiomen were privy to a lot of highly classified information that passed through their hands,” Harold Meeker, who was second in command at the message center, recalled. “They were all cleared for top secret.”

Yet some messages were so sensitive that not even Hannon or his coworkers were allowed to process them.

In one corner of the room stood a pair of encryption machines with a thick curtain that could be pulled for total privacy. Only three men — Meeker; Lieutenant John Rogers, the director of the message center; or his boss, Cmdr. Charles H. Garrison Jr. —were authorized to process the orders to, say, an attack submarine shadowing a Soviet missile submarine or conducting surveillance on a Soviet naval exercise.

As he approached the Marine guards, Hannon was still replaying in his head what he had told Ken Larbes the night before.

“She was on a 24-hour Check Report,” Hannon recalled, but both petty officers thought there must be an innocuous reason for the silence.

“It was no big deal because boats were always late for any number of legitimate reasons ranging from equipment malfunctions to ‘the radioman just forgot,’” Hannon said.

Still, the two radiomen were aware of a top-secret situation involving the Scorpion that suggested potential danger. The submarine had originally been scheduled to sail straight home from the Mediterranean to Norfolk, but on Friday, May 17, it had been ordered more than 1,000 miles southwest, down toward the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa. A group of Soviet navy warships, including at least one nuclear submarine, were operating in the area, and the U.S. Navy wanted to check them out.

At the gate that Thursday morning, Hannon flashed his ID to the Marine on duty, punched in the cipher lock code, opened the security door, and bounded up the stairs. Opening the door to the message center, he froze in his tracks. Instead of the normal half-dozen radiomen quietly at work, a large group of senior officers — including several admirals and a Marine Corps general — had taken over the workspace and were talking among themselves in hushed voices. Hannon had never seen any of them before.

Hannon instantly knew that something was seriously wrong. And when he looked past the high-ranking interlopers and saw the expression on his friend’s face, Hannon knew that something terrible had happened to the Scorpion.

Years later Larbes would describe how his overnight watch in the message center had begun at midnight in relative calm but had steadily become intense as more and more senior officers arrived on the scene.

“I had never seen a captain or an admiral come into that place in the two and one-half years I worked there,” he told me in an interview for this story.

“Now we had captains and admirals running around wanting more information [about the Scorpion]. It was so crazy…they suspended all of the saluting and all that.”

Within minutes of his arrival that morning, Hannon overheard conversations among the high-ranking strangers that made it clear that the Scorpion had disappeared and that its crew of 99 officers and enlisted men were dead.

Hannon, Larbes, and the rest of the radiomen didn’t realize at the time that they were witnessing the beginning of one of the greatest cover-ups in U.S. naval history: the burial of the truth of what had happened to the Scorpion.

The U.S. Navy’s suppression of the facts surrounding the loss of the Scorpion began in earnest five days after it disappeared, when the submarine failed to arrive in port as scheduled.

The official narrative — as told in Navy reports, news releases, and the transcript of a formal Court of Inquiry — is straightforward. A routine homecoming from sea suddenly escalated into a major crisis as the seven-year-old submarine inexplicably failed to appear at 1 p.m. on Monday, May 27.

The story of the missing submarine soon made the front pages of newspapers across the country.

According to the official account, the incident began unfolding in the morning hours of May 27. Officials at Submarine Squadron 6 in Norfolk were expecting the Scorpion to surface off the Virginia Capes in late morning and establish ship-to-shore radio contact before entering port.

The squadron staff had already arranged for a harbor tug to stand by and had mustered a working party of line handlers to tie the submarine to the pier on its arrival. Despite a fierce nor’easter that was lashing southeastern Virginia that morning, several dozen family members were huddled under umbrellas at the foot of Pier 22 with banners and balloons to welcome their men home from sea.

Officials had announced the arrival time three days earlier. Theresa Bishop, the wife of Torpedoman Chief Walter W. Bishop, the Scorpion’s Chief of the Boat, waited out of the rain with several friends in a car in the parking lot at the foot of the pier. She had left their three children at a friend’s house because of the storm.

Nearby was Barbara Foli, the wife of Interior Communications Electrician 3rd Class Vernon Foli. This had been the first overseas deployment for the young family. Barbara was so eager for a reunion with her husband and their infant daughter, Holli, that she had come out despite the storm.

“It was a very cold, very dreary morning,” she recalled years later. “The wind was sucking the umbrellas away.”

At the Submarine Squadron 6 office aboard the submarine tender Orion, no one yet suspected anything was wrong. Capt. James C. Bellah, commander of the support vessel, was acting squadron commander while its skipper, Capt. Jared E. Clarke III, was out of town on personal leave.

In late morning, Bellah stopped by the squadron office to ask if the Scorpion had broken radio silence.

“We haven’t heard anything from them,” a sailor replied.

Bellah left to return to his own office elsewhere on the Orion. Years later, he would describe how the mood shifted from no concern to stark worry in a matter of several hours.

“Up until 11 a.m., we weren’t that concerned,” he said. “We didn’t know there was a problem; we got no indication there was a problem with that submarine at all.”

But when the 1 p.m. arrival time came and went without a sign of the Scorpion, senior officials across the sprawling naval complex started to grow worried.

Informal alerts began going out to various unit headquarters.

At the Atlantic Fleet’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Force Command, the telephone rang at 2:15 p.m., and the duty officer received jolting news: Submarine Force Atlantic headquarters was requesting that the aviation command immediately launch long-range patrol aircraft from Norfolk and Bermuda to search for any sign of the Scorpion along its expected course in the western Atlantic.

An hour later Submarine Force Atlantic headquarters formally declared “Event SUBMISS” (submarine missing) and, further, ordered all “units in port [to] prepare to get underway on one hour’s notice.”

By nightfall, most of the waiting families had gone home, still unaware of the emergency. They’d been told only that the submarine had not yet broken radio silence to signal its approach to port and that bad weather was the most likely reason. None of them knew that the Atlantic Fleet was scrambling to sea to hunt for the submarine.

Then, shortly after 6 p.m., WTAR-TV, the CBS affiliate in Norfolk, citing anonymous Navy sources, reported that the Scorpion was missing.

While the submarine was nearing the end of its Mediterranean deployment, Sonar Technician 1st Class Bill Elrod, a crewman on the Scorpion since 1964, had received devastating news: His wife, Julianne, had gone into labor on May 16, but the baby had died at birth.

Cmdr. Francis A. Slattery had diverted Scorpion to the harbor at Rota, Spain, where Elrod and another crewman transferred to a tug and proceeded ashore to fly back to Norfolk.

On Monday, May 27, Elrod had reported aboard the Orion and volunteered to help with his submarine’s pending arrival. In the late afternoon, with no word as to its status, Elrod returned home to their apartment in Norfolk, where Julianne was waiting for him.

At 6 p.m. Elrod turned on the TV to the local news and heard the bulletin about the Scorpion.

“It was over,” he later recalled saying to himself. “They never, never announced anything like that. When they announced it on television, I knew the boat was gone.”

Several miles away, Theresa Bishop was preparing dinner for her three children when her eight-year-old son walked into the kitchen and said, “There’s something on TV about the Scorpion missing.”

“I went totally numb,” Theresa later recalled. “Nobody said anything. We just sat around waiting for the telephone to ring.”

Friends and neighbors began arriving at the Bishop home for the first of many long nights of watching and waiting. At one point later in the evening, Theresa Bishop stepped out to listen to the storm that still raged overhead but then heard something else.

From the naval station piers five miles away came a muted chorus of sirens, foghorns, and klaxon alarms as several dozen Atlantic Fleet ships began putting to sea to search for her husband’s missing submarine.

Unlike many of his fellow radiomen at the Atlantic Submarine Force message center, Hannon had actually served on board a submarine, earning his prize Dolphins insignia in the one-of-a-kind nuclear sub Triton before his assignment ashore.

Because of their familiarity with submarine operations and customs, Hannon and his boss, Warrant Officer John Walker, another submariner, were given the responsibility of handling a number of communications activities related to the submarine’s disappearance, particularly the massive search effort.

“I encoded and decoded messages sent to higher command and to several ships and subs in approximate proximity to Scorpion’s last known position,” Hannon later recalled. “However, there were [also] messages sent up the ladder seeking guidance on how to handle the event relative to the press.”

From that vantage point, Hannon watched in growing dismay and anger as the Navy buried the truth of what had happened to the Scorpion.

He was particularly upset to learn that on Friday, May 24, COMSUBLANT officials — knowing full well the Scorpion was already lost with all hands — had announced that it would be arriving at 1 p.m. the following Monday, and worse, had said nothing three days later to dissuade several dozen family members from standing vigil for hours in the raging nor’easter.

By Tuesday morning, May 28, the story of the missing submarine led the front pages of newspapers all over the country. The previous evening, in an impromptu news conference at the Pentagon, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Thomas H. Moorer had offered a slender reed of hope to the families of the crew.

“The weather is very, very bad out there,” Moorer told reporters. “But the weather may abate. The ship may well have been held back [by the storm], and she could proceed into port.”

This was another lie. Moorer, too, knew that the Scorpion had in fact sunk five days earlier, on May 22 — less than eight hours before the panicked group of senior officers began cramming into the COMSUBLANT message center.

For the next week, dozens of Atlantic Fleet ships and patrol aircraft scoured the open ocean. After several days, the search effort shrank to five destroyers, five submarines, and a fleet oiler proceeding in two groups down the Scorpion’s course track from its last known location southwest of the Azores toward Norfolk.

The two groups, positioned 12 hours apart for maximum surveillance, steamed in a line abreast measuring 48 miles wide as their lookouts peered intently through binoculars and their radar operators stared at their scopes for any sign of the missing submarine.

They found nothing.

Hannon’s next shock came two weeks after that late evening when he had told Ken Larbes about the submarine’s missed Check Report.

Picking up the Virginian-Pilot newspaper on the morning of Thursday, June 6, Hannon read that the three-star admiral commanding the Submarine Force Atlantic had, the day before, testified under oath as the leading witness before a formal Court of Inquiry into the Scorpion’s disappearance.

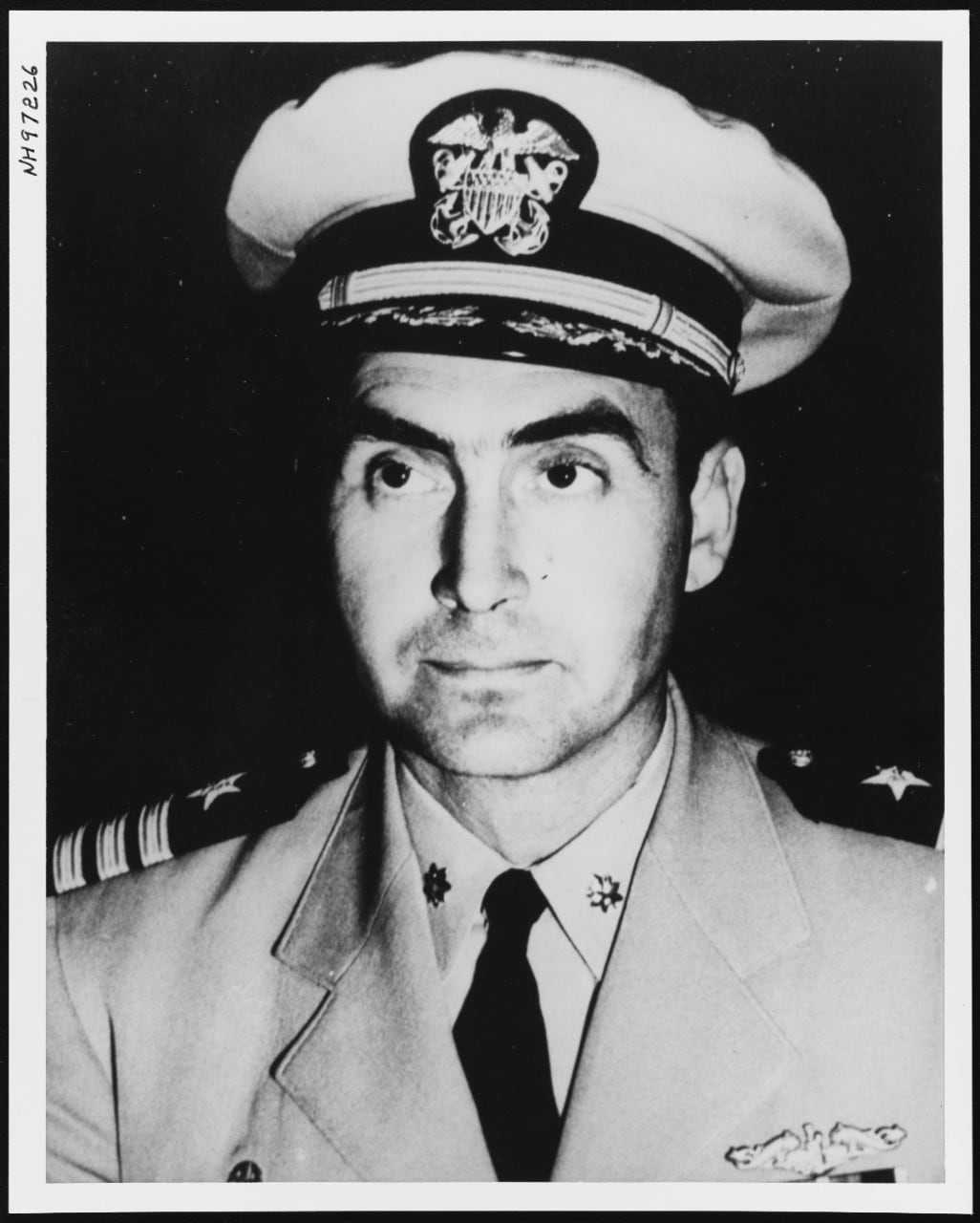

The admiral’s account flatly contradicted what Hannon and his fellow radiomen had seen and heard. Rather than describing the overdue Check Report and the crowd of senior naval officers who had clogged the message center the next morning, Vice Adm. Arnold F. Schade’s sworn statement made no mention of any of the events in the five days before May 27.

As Schade described it, the emergency had not begun until that rain-swept Monday afternoon when the Scorpion failed to arrive back in Norfolk on schedule.

No members of the Court of Inquiry challenged the three-star admiral’s testimony.

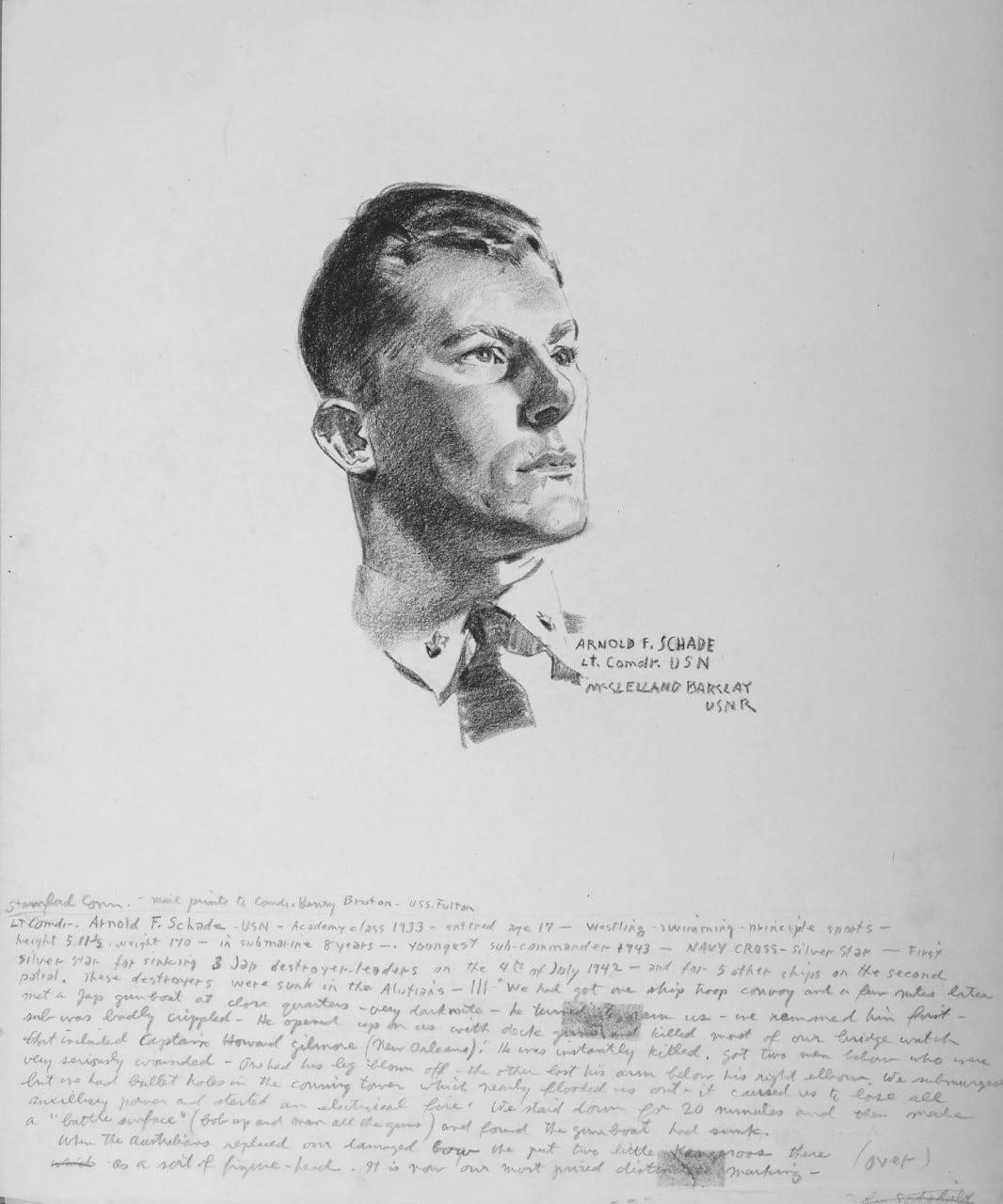

Schade, 56, was a revered figure in the Submarine Service — a combat veteran of 11 submarine patrols against the Japanese in World War II and the recipient of a Navy Cross for extraordinary courage in combat.

He was the perfect lead witness before the seven-member panel. It was Schade who had selected the Scorpion for the Mediterranean as a last-minute replacement for the Seawolf, the navy’s second-oldest nuclear submarine, which had suffered serious damage in an underwater grounding off the coast of Maine on January 30, 1968.

His intelligence section provided Cmdr. Slattery with vital information to carry out the Scorpion’s various missions. Schade’s operations staff controlled the submarine’s every movement before and after its three-month deployment with the Sixth Fleet, including the last-minute assignment to spy on Soviet warships off the Canary Islands.

If anyone could unlock the mystery of the Scorpion’s disappearance, it was Arnie Schade.

After offering a lengthy review of the search for the Scorpion and a summary of its Mediterranean deployment, Schade revealed that COMSUBLANT had dispatched unspecified “exercise instructions” to Slattery once the submarine had entered the Atlantic, including a directive to report its position on or about Tuesday, May 21.

The final message received from Scorpion dated 2354Z (7:54 p.m. EDT) on May 21, Schade said, “gave her position at 0001Z [8:01 p.m.]” and “reported that she would arrive in Norfolk [at] 271700Z [1 p.m. on Monday, May 27].”

After further discussion about the search conducted in the shallow waters off the Virginia coast, Schade took questions from Capt. Nathan Cole Jr., counsel for the court:

Q. Now, I believe you did state that it would be normal, you would not expect to hear from Scorpion after she filed her posit[ion] report and got underway returning home until she got here. Is that correct, sir?

A. That is correct.

Q. Is this normal, Admiral?

A. It is quite common practice. As you know, our Polaris [missile] submarines go out for 60-day patrols and never broadcast except in most extraordinary circumstances. And frequently our submarines are sent out on exercises which eliminate any requirement for reporting. It is only normal to expect Check Reports and continuous communications both ways when submarines are operating in the local areas when the exercise ground rules so provide.

And so it went for the next four weeks as the Court of Inquiry took testimony from 75 witnesses and examined hundreds of pages of exhibits relating to the Scorpion’s deployment, maintenance history, and other areas.

Not a single witness revealed what the COMSUBLANT message center staff had known all along: that the Scorpion emergency had begun in the late evening of Wednesday, May 22.

On July 26, 1968, the court submitted its classified report and adjourned. But in late October came the stunning news that the wreckage of the submarine had been found.

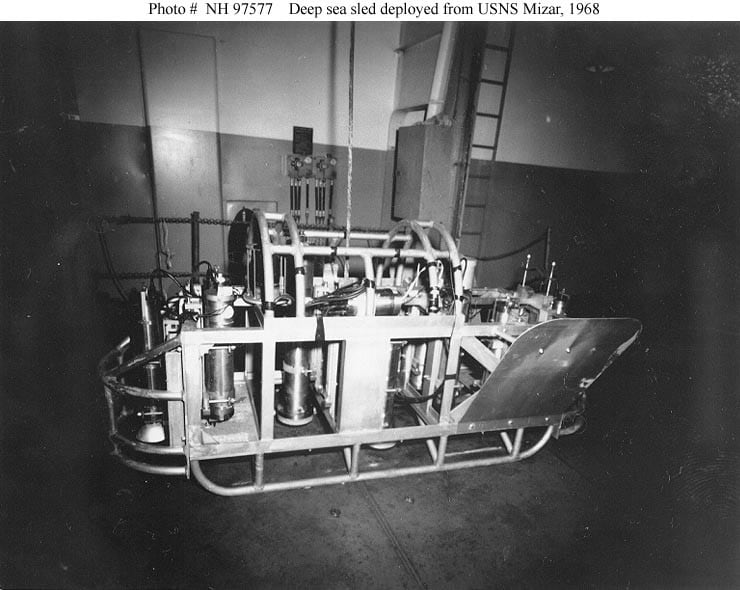

The Scorpion’s shattered hull had been photographed by a camera mounted on an unmanned “sled” tethered to a three-mile-long cable towed by the research ship Mizar, which for weeks had been searching a 12-square-mile area southwest of the Azores where officials calculated the wreckage lay on the seabed two miles down.

The court’s panel reconvened on Nov. 5 and spent several weeks examining hundreds of images of the wreck. It then went into executive session to write an addendum to its report.

Even so, when the Navy finally released an unclassified summary of the court’s findings on Jan. 31, 1969, the conclusion was disappointingly vague: “The certain cause of the loss of Scorpion cannot be ascertained from any evidence now available.”

One of the great ironies of the long saga of the Scorpion is that the man most instrumental in revealing the truth about the lost nuclear attack submarine was the official who tried the hardest to keep the full story secret — Vice Adm. Schade.

Fifteen years after the Scorpion went missing, Schade agreed to provide his recollections of the incident in a telephone interview from his home in Florida, a conversation whose revelations would fatally impeach, albeit perhaps unintentionally, the official account of the submarine’s disappearance.

On April 27, 1983, the admiral cleared his throat and began to describe the Scorpion’s departure from the Mediterranean just after midnight on Friday, May 17, 1968.

“When they were coming out [of the Mediterranean], we normally diverted them into the Polaris base at Rota, Spain, for a couple of days for a [torpedo] load-out and [to obtain] a couple of things they might need before leaving the area. And [Scorpion] reported that their condition was so good that they didn’t even need to stop," he said.

Schade then confirmed a finding of the Court of Inquiry that a Soviet naval exercise that included at least one nuclear submarine was underway southwest of the Canary Islands.

“We had general information of a [Soviet] task force operating over in that general area. So we advised [Scorpion] to slow down, take a look, see what they could find out. As far as we know they never made contact, they never reported on that.”

Then Schade unwittingly dropped his first bombshell.

“They were due to report in to us shortly thereafter,” Schade went on, referring to the three-day period cited by the court — May 19 through May 21 — in which the Scorpion’s surveillance of the Soviet warships was to have taken place.

“It was at that time we got a little suspicious, because they did not report,. They did not check in, and then when we got to the time limit of their check-in they were first reported as overdue," he said.

Schade had inadvertently contradicted his own sworn testimony to the Court of Inquiry 15 years earlier. Now, for the first time, Schade was admitting that the Scorpion indeed had been on the Check Report system, and thus was required to transmit the encrypted message — “Check 24. Submarine Scorpion” — each day.

Asked to amplify, Schade noted that Slattery had transmitted a position report whose heading read “212354Z May 68,” or 2354 GMT (7:54 p.m. EDT) on May 21.

“As far as we were concerned all was clear, and she should have kept coming. And then, within about 24 hours after that, she should have given us a rather long, windy, résumé of her operations …. And when they did not respond, almost immediately that’s when we first became suspicious, that’s when we followed up with other messages, and really, it was just a matter of hours that we became somewhat concerned," he said.

Schade was explaining that instead of first sounding the alarm on May 27 after the Scorpion failed to arrive as scheduled, his command knew something was wrong with the submarine within hours of its actual sinking — a full four days earlier than officials had ever admitted.

And then he dropped his second bombshell.

Schade recalled that he had been out at sea when word came that the Scorpion had failed to send its Check Report.

“It looked like we needed to do something in the way of a search operation, [and so] I got Adm. Holmes [Ephraim P. Holmes, the commander of the Atlantic Fleet] on the radio and said, ‘Would you place the facilities of CINCLANTFLT [the Atlantic Fleet] at my disposal for the next day or two until we can organize a search operation?’ In fact, he placed them all at our disposal, and this was quite an amazing set of operational circumstances, because we controlled the entire resources of the Atlantic Fleet from a submarine at sea. Working through CINCLANTFLT headquarters and their communications, we organized a search from both ends [of the Scorpion’s presumed course] both by air and surface ships and other submarines.”

Surprised by this totally unexpected disclosure — a secret search for the Scorpion mounted at least four days before the Navy was supposed to have known anything was amiss — I asked Schade once again to clarify, and he did.

“All I know is that long before she was actually due in Norfolk, we had organized a search effort,” Schade said. “We had two squadrons of destroyers, a lot of long-range antisubmarine search planes operating out of the Azores, Norfolk, and other areas, and we had several ships that were in the Atlantic that were in transit between the Med and the U.S. Some [were] diverted and some of them were just told to come over to the track which we presupposed the Scorpion would be on. They searched up and down that [corridor]. This went on for quite some time, until it was quite obvious that she was long overdue arriving in Norfolk.”

Schade’s disclosures about the Scorpion set in motion a research effort that would occupy me, on and off, for the next 24 years.

During that time the U.S. Navy declassified most — but not all — of the official Scorpion archive.

And after his arrest in 1985, John Walker, who had been the supervisor on duty at the COMSUBLANT message center the night the Scorpion disappeared, pleaded guilty to spying for the Soviets and selling top-secret materials that enabled them to “break” encrypted submarine communications. Nevertheless, to this day U.S. Navy officials insist that Cmdr. Slattery and his 98 crewmen perished as the result of some unknown malfunction, not from any sinister event.

More than four decades after the disappearance of the Scorpion, Mike Hannon and Ken Larbes decided to break their silence.

In 2010, after reading my book on the disappearance of the Scorpion, Hannon contacted me and revealed the final secret of the submarine that he and Ken Larbes had discovered in the tense hours of May 22–23, 1968: The senior officers crowding into the COMSUBLANT message center arrived already knowing that the Scorpion was lost — and why.

Larbes, in an interview in 2018, confirmed Hannon’s account.

“There were officers openly discussing the fact that they believed the Scorpion had been sunk,” Hannon told me.

He also said he overheard that the Scorpion’s sinking had been tracked by the navy’s top-secret Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), a network of underwater acoustic sensors used to monitor and track both submarines and surface vessels.

The SOSUS hydrophones in the Atlantic “did hear the explosion,” Hannon said.

And, he added, “a Soviet submarine was tracked leaving the area at a high rate of speed.”

What Hannon, Larbes, and the other radiomen learned that fateful Thursday in May 1968 — and in the weeks that followed — is stark confirmation that the Navy’s expressed shock and surprise over the missing submarine was a sham.

At the heart of the Submarine Force Atlantic, key officials knew practically from the moment of its loss that the Scorpion went down during a confrontation with a Soviet submarine.

Their immediate response was to bury the truth as deep as the remains of the Scorpion itself.

RELATED

Ed Offley is the author of Scorpion Down—Sunk by the Soviets, Buried by the Pentagon: The Untold Story of the USS Scorpion (Basic Books, 2007). This article first appeared in the Summer 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History, a sister publication of Navy Times.