The Orkney Islands lie seven miles northeast of the town of John O’Groats, Scotland, separated from the mainland by the Pentland Firth. In the middle of the seven islands of Orkney is the large natural anchorage known as Scapa Flow.

The area is largely deserted today, apart from the odd oil tanker serving North Sea oil rigs or, every two or three years, warships of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization meeting to conduct a joint exercise.

But in its glory days, the Flow served as the main base for Britain’s battle fleet during two world wars.

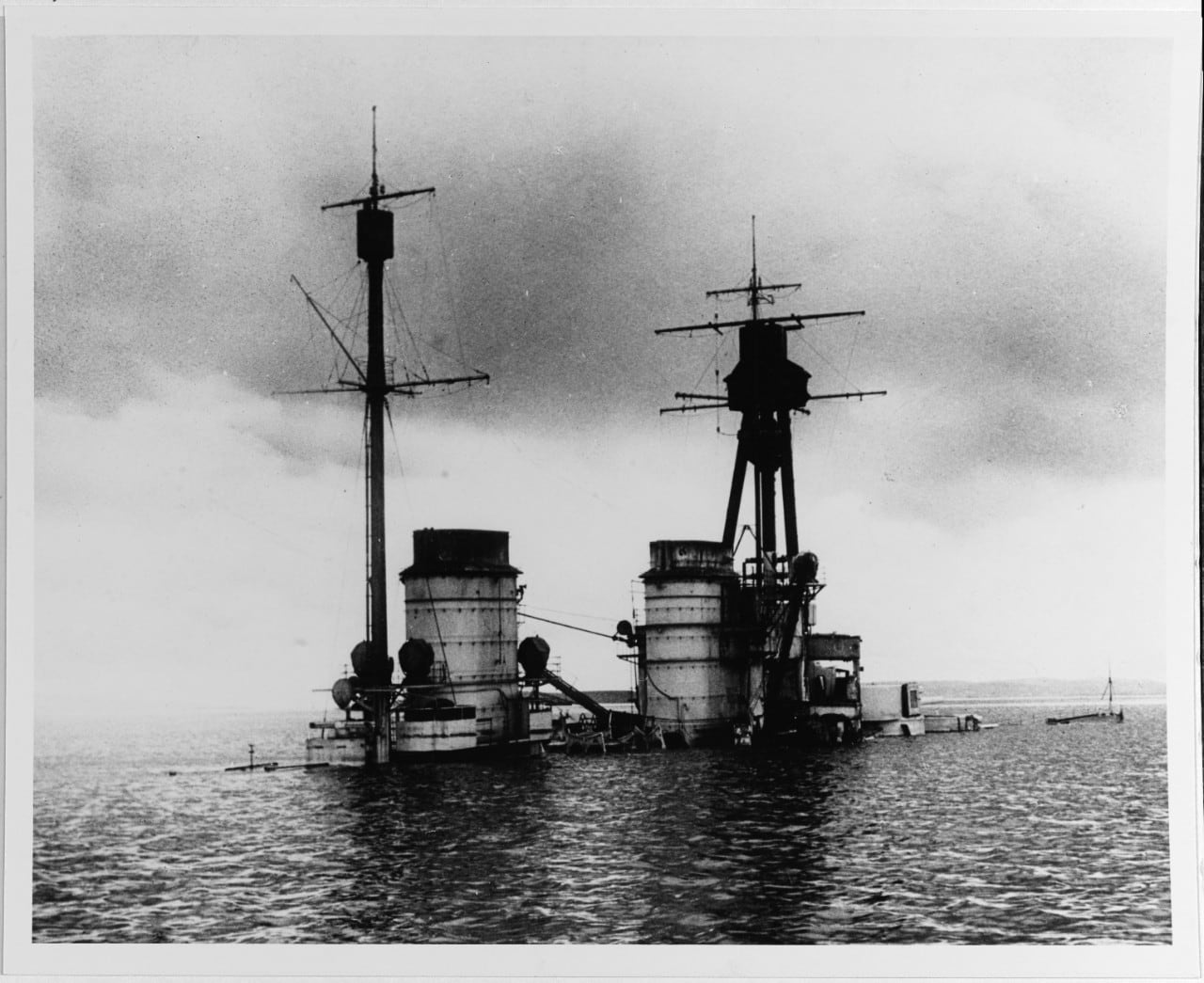

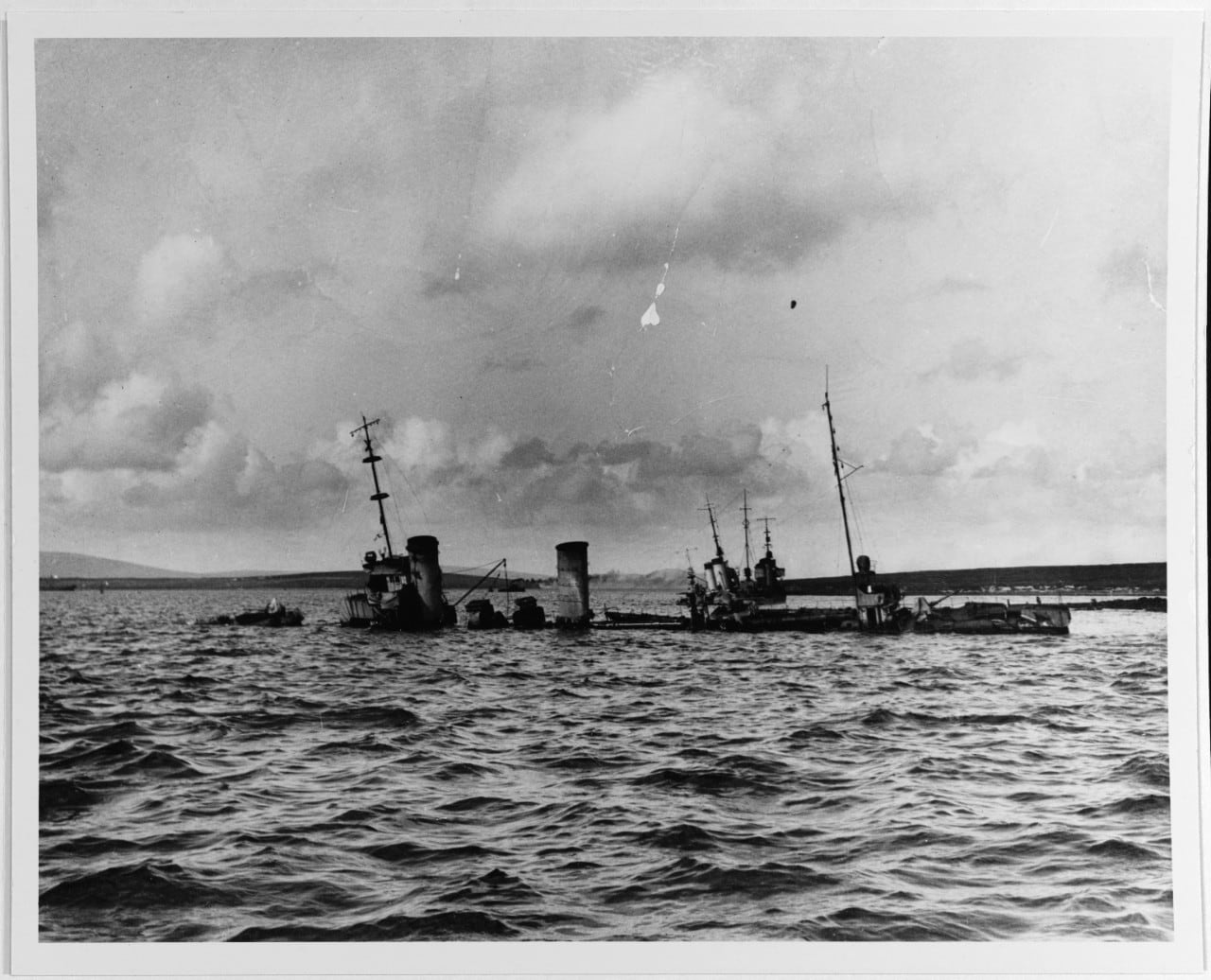

Just a few fathoms below Scapa Flow’s dark surface lie the remains of another navy: four battleships and four light cruisers of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet, scuttled by their own crews in 1919 in the largest act of self-destruction in naval history.

The fleet that died by its own hand on that first summer day of 1919 was the product of one of history’s greatest strategic blunders. Between 1898 and 1914, a sudden surge of shipbuilding fervor expanded the Imperial German Navy from a largely coastal force to the second largest fleet in the world, equipped with some of the finest warships afloat.

Its creator was Capt. Alfred von Tirpitz, who in 1894 wrote a thesis for the Naval Supreme Command, in which he argued for a strong fleet.

The document might have been merely filed and forgotten, had it not come to the attention of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The German emperor loved ships. He had been consumed with envy when he attended his grandmother Queen Victoria’s review of the Royal Navy during the celebration of her Golden Jubilee in 1887.

Wilhelm also had visions of a German empire that extended overseas, like those of Britain and France. To build such a colonial and commercial empire required a deep-water fleet, capable of fighting full-scale battles anywhere on the globe.

When Chancellor Otto von Bismarck forged a united German nation in 1871, he saw no use for a large navy.

Germany’s future, he concluded, logically lay on the European continent, guarded by the most modern army in the world.

Crown Prince Wilhelm and the ‘Iron Chancellor’ soon clashed over their nation’s geopolitical role. Then, in 1890, the young Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had been on the throne for barely a year, forced Bismarck to resign.

With the old chancellor’s restraining hand gone, the kaiser turned his attention to realizing his great dream of a powerful navy — a dream for which Tirpitz became the chief architect.

Tirpitz put forward his “risk theory,” arguing that it was not necessary for the German fleet to defeat a rival power in battle but simply to be capable of inflicting enough serious damage to cripple or disrupt the enemy’s supremacy at sea. Therefore, the mere existence of a powerful fleet would give Germany a degree of control over her rival. Although Tirpitz did not name Britain in his discourse, there could be no doubt that she was the rival naval power to which he referred.

Constructing the navy that the kaiser and Tirpitz desired was an immense task, although starting from scratch did have its advantages. In Britain, ships had to be designed and built within the limiting dimensions of existing docks. The new docks constructed in Germany were more up-to-date, allowing for the construction of larger-beamed and stronger warships.

And so Germany embarked on a course to end more than a century of naval supremacy Britain had enjoyed since the days of Horatio Nelson.

Wilhelm and Tirpitz, however, had not bargained on Britain’s determination to maintain that dominance, nor did they give weighty consideration to what might happen if Britain were aroused from her traditional isolation from Continental affairs. They assumed that Britain and Russia, who had opposing interests in the Far East, would never work together. France was also ruled out, because of her centuries of rivalry with Britain — and because of her alliance with Russia. The Germans also seriously misjudged the industrial might available to Britain and her empire as well as the natural advantage of her centuries of naval experience.

Britain had long mistrusted Germany but was willing to accept her as the foremost land power on the Continent. The alteration in the balance of power caused by the naval race, however, did much to end British non-involvement in European affairs — and not to Germany’s advantage.

A treaty with the small but growing naval power of Japan in 1902 gave Britain an ally to counter German colonial ambitions in the Far East. In 1905, Britain, alarmed by German naval expansion, reached an understanding, or Entente Cordiale, with France. In 1907, Britain and Russia set aside their long-standing rivalry over India and Persia to form a triple alliance with France against potential German aggression.

Kaiser Wilhelm was compelled to offset that powerful block by forging his own alliances with Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Turkey, Bulgaria and a half-hearted Italy — all far weaker partners. Thus, the German folly of starting a naval arms race can be seen as one of the principal causes of World War I.

On the eve of war in July 1914, Britain had 43 battleships, with 13 more being built, while Germany had 31, with 10 more under construction.

Those figures did not tell the whole story, however. Of Britain’s capital ships, 24 were of the modern dreadnought design, whereas Germany had only 13 such ships in commission.

Ship for ship, there was little to choose between them. The battleships of the Royal Navy generally carried bigger guns, were faster and had greater range.

The German ships had more watertight compartments, better armor and superior fire control.

In regard to cruisers, the workhorses of the fleets, Britain had a healthy lead — 70 to Germany’s 38.

Perhaps more important, while the Royal Navy covered the Channel, North Sea and Atlantic Ocean, the French navy took over responsibility for the Mediterranean Sea, effectively neutralizing the small navies of Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Italy (the last of which would go over to the Allied side in May 1915).

It soon became apparent to the German naval command that it had no hope of winning a full-scale encounter with Britain’s Grand Fleet.

The Germans knew that the British would use their standard tactic of blockading the coast, so they planned to gain local supremacy by destroying isolated squadrons engaged in that blockade. In time, they hoped, the Royal Navy’s lead would be reduced, to the point where the High Seas Fleet could square off with the Grand Fleet on even terms.

Again, however, the Germans’ assumptions were faulty. The British did impose a wartime blockade, but it was not the close blockade they had used so often in the past. Instead, the Royal Navy opted for a distant blockade, covering the Channel and the gap between Norway and the Orkney Islands. That gave the British the time to concentrate their naval forces in response to any reported threat from the German fleet.

Although German cruisers and commerce raiders displayed great daring and skill in the early months of the war, by mid-1915 Germany’s regular warships overseas had been either sunk or driven back into their home ports.

On only one occasion did the two great fleets meet in battle. Commencing on May 31, it was an epic but inconclusive affair, fought in overcast weather with hundreds of ships adding thick, acrid smoke from their funnels and guns to the fog of battle.

The Germans called it the Battle of the Skagerrak, while the British called it Jutland.

The German commanders displayed more nerve than their opponents during the battle. On two occasions, they extricated their fleet from dangerous situations. It can also be said, however, that they were allowed to escape because of poor British communications and because of Adm. Lord John Jellicoe’s fear of torpedo attacks against his massed battleships.

As Winston Churchill indicated afterward, the overly cautious Jellicoe and the impulsive Adm. Sir David Beatty were the only men on either side who could have lost the war in an afternoon.

After disengaging and returning home on June 1, the Germans claimed a tactical victory because more British ships had been sunk.

The Grand Fleet had indeed lost the well-armed but brittle battle cruisers Invincible, Indefatigable and Queen Mary, which prompted Beatty to remark, “There’s something wrong with our bloody ships.”

The British battle cruiser commander’s own flagship, Lion, was only saved from being blown up when wounded Royal Marine Maj. Francis Harvey ordered the burning magazine of ‘Q’ turret to be flooded, for which he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The Grand Fleet also lost four cruisers and seven destroyers, representing a loss of 111,000 tons or 8.84 percent of its strength. A total of 6,784 Royal Navy men were killed, wounded or captured.

In comparison, the High Seas Fleet lost the battle cruiser Lützow, the pre-dreadnought battleship Pommern, four cruisers and four destroyers. That amounted to 62,000 tons, or 6.79 percent of its strength, while 3,058 German seamen were killed or wounded.

Based on those statistics, the German tactical claim would appear just, but the battle did not alter the strategic picture at all.

In spite of his losses, when Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet returned to Scapa Flow, he was able to signal the Admiralty that he could return to sea on four hours’ notice.

His German counterpart, Adm. Reinhard Scheer, told the kaiser upon returning to Wilhelmshaven that his fleet would not be ready for sea until mid-August.

That was mainly due to the heavy damage inflicted on many of the German ships, a factor that is not reflected in the figures regarding warships sunk.

The battle cruiser Seydlitz, for example, was struck by 22 large-caliber shells and one torpedo, but it managed to limp home with her bows practically awash. Its very survival was a tribute to her builders at Hamburg and to the skill of her crew.

An American newspaperman succinctly summed up the battle’s strategic outcome when he reported, “The German Fleet has assaulted its jailer, but it is still in jail.”

After Jutland, the German navy turned its attention to unrestricted submarine warfare — a clear admission that the High Seas Fleet had failed to achieve its objective.

Submarine warfare, like Gen. Alfred von Schlieffen’s plan to invade France via Belgium, was intended as a shortcut to victory. It, too, failed, because British Prime Minister David Lloyd George insisted, against the advice of his admirals, that the Royal Navy adopt the convoy system.

On the other hand, German submarine attacks on neutral shipping brought the United States into the war on April 6, 1917.

Despite the capitulation of revolution-wracked Russia, Germany still faced an overwhelmingly strong coalition with a new Allied power in mid-1917.

By August 1918, the German army was reaching the end of its endurance, but the High Seas Fleet was virtually intact. The admirals still plotted to lure the Grand Fleet into a last great battle — one that they might not win, but which they hoped would show German resolve to fight on and which, in turn, might influence any peace negotiations to their advantage.

When Adm. Franz von Hipper led the High Seas Fleet out to sea on October 29, it was materially stronger than it had been at Jutland. The crewmen, however, saw no future in this defiant gesture, which took little account of their lives, and a mutiny broke out.

Hipper managed to restore a brittle discipline, but with unrest still simmering, he prudently abandoned the operation. Putting the mutiny’s leaders in irons only served to aggravate the already deteriorating morale among the ranks. Once they were back in port, unrest spread throughout the fleet.

In November, it was all over. Communist uprisings in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven resulted in control of the fleet passing into the hands of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils.

Chaos pervaded the country. Entire divisions at the front refused to fight, and many ships were seen raising the Socialist revolutionary red flag. The government promised the mutineers that the fleet would not be sent out on any sacrificial sorties, essentially rendering its powerful warships impotent.

On Nov. 11, 1918, Germany signed an armistice, ending World War I. In Article XIII of the armistice agreement, the Allied naval council decreed that the German fleet should be confined to port under their supervision.

The victorious Allies also demanded that 10 battleships, six battle cruisers, eight cruisers, 50 destroyers — all ships of the most modern type — and the entire submarine fleet be handed over for internment. The designated surface vessels were to be dismantled so that they carried no armament and then interned in neutral ports.

No neutral country could be found that was willing to play host to them, however. The Allies only approached Spain on the matter, and she refused. German efforts to find a haven for their commandeered warships, though more extensive, proved to be equally fruitless. The Allied council then came to the decision that the only safe place for such a large force was Scapa Flow, where it could be watched by the Grand Fleet.

The Germans were told that the ships designated for internment must be ready to sail on Nov. 18. If they failed to comply, the Allies would seize Heligoland and sink the ships in their ports.

Any renewal of hostilities would be disastrous for Germany, but few men in the fleet believed that their ships would be made ready in time to meet the deadline. The Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils had eroded the officers’ authority, while the crews had been depleted by desertions and an influenza epidemic.

Preparations did not merely involve steaming to Scapa Flow. Armaments had to be removed or rendered useless. It was no easy task to remove the breechblocks from 15-inch guns. Much of that expensive equipment was torn or burned out and dumped on the quays or simply cast overboard.

Rear Adm. Ludwig von Reuter was requested, rather than ordered, to carry out the unenviable task of leading the fleet into internment.

He wrote in a report that “personal feelings had to step to the rear.”

However repugnant the mission, he was still serving his country.

Reuter was already considering the option of sinking the fleet, however, in anticipation of any British action that would exceed the articles of the armistice. ‘Any betrayal would give us back our freedom of action,’ he wrote. ‘We could do what we liked with our ships, we could also sink them.’

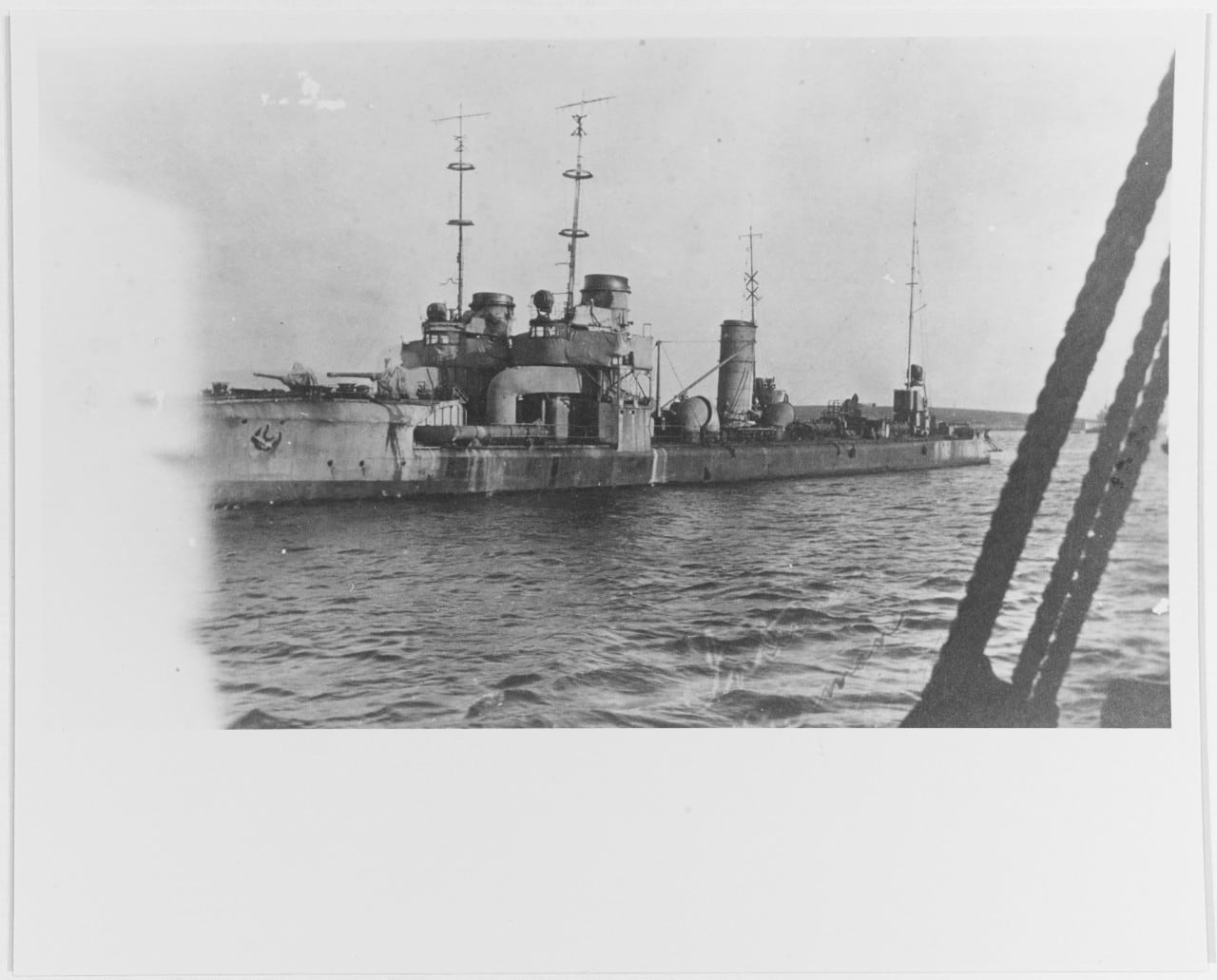

Reuter took command on Nov. 18. The High Seas Fleet departed on the 19th and was ready to meet the Allied escorts on the 21st.

Rear Adm. Hugo Meurer, who had negotiated the details of internment, was told by Beatty that ‘a sufficient force will meet the German ships.

“That’sufficient force” was composed of the Grand Fleet (commanded by Beatty since he had succeeded Jellicoe in November 1916), an American battleship squadron and representative vessels from the other Allied navies — 250 warships in all.

At 8:30 a.m. on Nov. 21, as the High Seas Fleet steamed up in line-astern formation in accordance with Beatty’s orders, “Action Stations” was sounded aboard the British ships. Seamen rushed to their stations, rigged in full war kit. The great guns of the capital ships were not loaded, but ammunition had been brought up from the magazines. Gun directors were laid on and ranges passed, just in case.

Lt. John Ouvry on the light cruiser Inconstant wrote in his diary: “The excitement was of course intense as it was impossible to tell whether the Hun had something up his sleeve for us or not. It seemed too wonderful for an extremely powerful fleet to give themselves up without a blow.”

A haze descended over the area that morning, reducing visibility. ‘

“Thus heaven conferred a certain mantle on our shame in the form of a light veil of mist,” wrote Reuter, and “the most tremendous tragedy ever enacted at sea was thereby softened to the view.”

It was a rare expression of emotion from the usually stoic Prussian admiral.

A lieutenant aboard the U.S. Navy battleship New York described the procession from his perspective:

The tiny light cruiser Cardiff, towing a kite balloon, leads the great German battle-cruiser Seydlitz, at the head of her column, between our lines. On they pass — Derfflinger, Von der Tann, Hindenburg, Moltke — as if on review. The low sun glances from their shabby sides. Their huge guns, motionless, are trained fore and aft. It is the sight of our dreams, a sight for kings! Those long, low, sleek-looking monsters, which we had pictured ablaze with spouting flame and fury, steaming like peaceful merchantmen on a calm sea. The long line of battleships, led by Friedrich der Grosse, flying the flag of Admiral von Reuter, commanding the whole force, König Albert, Kaiser, Kronprinz Wilhelm, Kaiserin, Bayern, Markgraf, Prinz Regent Luitpold, and Grosser Kürfurst followed in formation — powerful to look at, dangerous in battle, pitiful in surrender….

Sensing the humiliation of his former adversaries but displaying little compassion for them, Adm. Beatty described the sight with a measure of disappointment and contempt: “We never expected that the last time we should see them as a great force would be when they were being shepherded, like a flock of sheep, by the Grand Fleet. It was a pitiable sight; in fact I should say it was a horrible sight….”

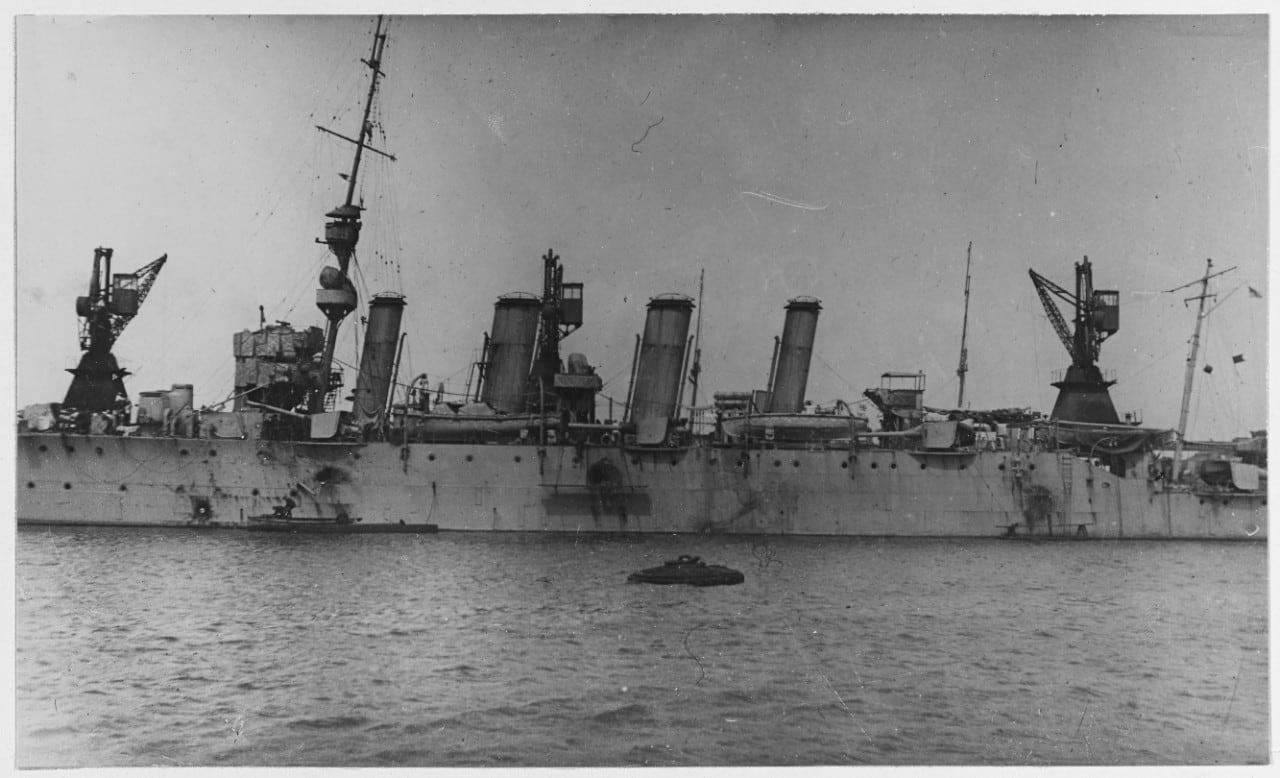

The ships were escorted to the Firth of Forth, where they were inspected by boarding parties. At sunset, the German ensigns were lowered, and Beatty ordered that they were not to be raised again. A few days later, all the ships were moved to Scapa Flow.

By Dec. 13, the captive fleet’s manpower had been reduced to caretaker scale.

Of the 20,000 men who had brought the ships into internment, only 4,565 remained. Radios were forbidden on the ships, and Reuter and his officers were forced to rely on four-day-old British newspapers to keep up with current events.

For months on end the crews experienced boredom in their uncomfortable steel homes. The ships deteriorated through neglect. Discipline was almost nonexistent, although Reuter managed to have the worst agitators sent home.

The Allies continued to argue about the fleet’s fate. The British, naturally, did not want the ships given to other powers, even their allies. Reuter became bitter over his government’s apparent lack of effort to salvage part of the fleet.

“It was quite clear to me that I should be left entirely to my own devices,” he wrote. “I had refused orders and instructions because I alone and nobody at home could assess and appreciate the situation in the Internment Formation.”

Pathetic as the German crewmen had seemed to the British officers who first boarded their ships, the crew’s mood began to change in the months that followed. Irritated by sightseers frequently passing by in small boats, gaping at the Germans like animals in a zoo, the crewmen’s general attitude turned from dejection to resentful defiance.

On May 31, 1919, they celebrated the third anniversary of the Battle of the Skagerrak — and disobeyed Beatty’s specific order — by hoisting the German naval ensign along with the revolutionary red flag up their yardarms.

Then, in June, Reuter learned that the German government had refused to ratify the naval terms of the Treaty of Versailles, even as the November 1918 armistice was nearing its expiration date. At the same time, rumors spread of a British plot to seize the ships.

At that point, Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet. Only news of his country’s decision to accept the peace terms would reverse his decision.

The British were well aware of the possibility of scuttling, but under the internment agreement they were not allowed to post armed guards on the German ships. Reuter kept his plans secret to all but a few key officers and men.

On June 20, however, he heard that crewmen aboard two of the battleships had learned of his secret plan. Then, on that same evening, he read in a June 16 edition of the London Times that the Allies had given Germany an ultimatum: Accept the peace terms by June 21 or hostilities would be renewed.

What Reuter did not know was that on the same day he was reading his four-day-old newspaper, his government had accepted the armistice terms, the deadline for which had in any case been extended to June 23.

The weather was unusually good on the morning of June 21 — not the usual combination of fog and rain. The sea was calm and the sky cloudless.

On board the light cruiser Emden, which was then serving as his flagship, Reuter came up on deck wearing his full-dress uniform, with medals. Deep in thought, he paced up and down the quarterdeck.

Just before 10 a.m., his chief of staff delivered an oral report informing him that the five British battleships that had guarded the Germans for so many months had left Scapa Flow — as luck would have it, the battle squadron had gone to conduct an exercise at sea earlier that morning.

Shortly after receiving that news, Reuter had the code flags “D.G.” raised on Emden, alerting his fleet to stand by for further signals. Then, at 10:20, more flags went up, communicating the message: “Make Paragraph II. Acknowledge.”

That harmless-looking order was in fact the prearranged signal for the entire High Seas Fleet to prepare to scuttle its ships. When his ships confirmed that his order was being carried out, Reuter sent up another signal: “Condition Z — scuttle!”

Reuter then gave Emden‘s captain his personal permission to do the same. German naval ensigns shot up the masts, while belowdecks seacocks and condenser intake valves were opened.

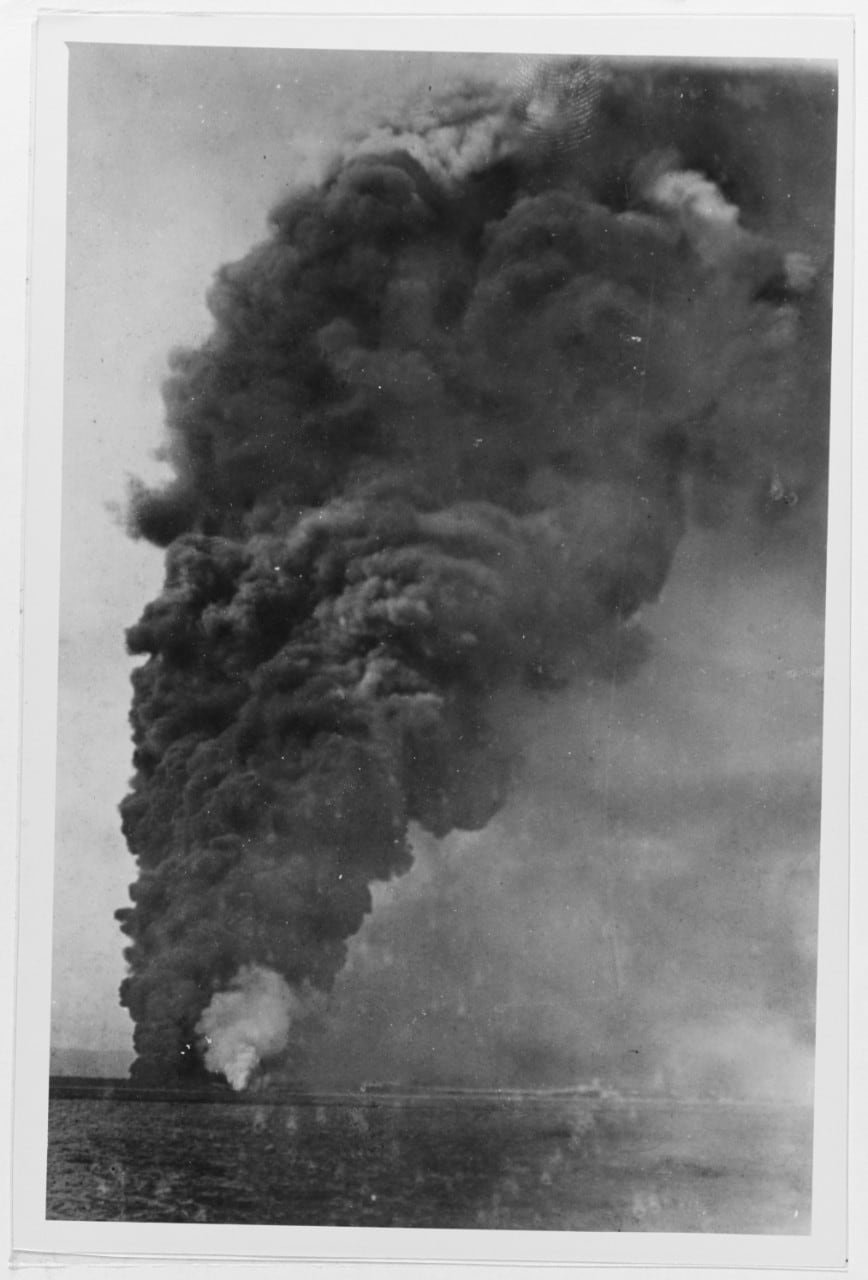

At 12:16 p.m., the battleship Friedrich der Grosse turned over and sank, the first ship to go down.

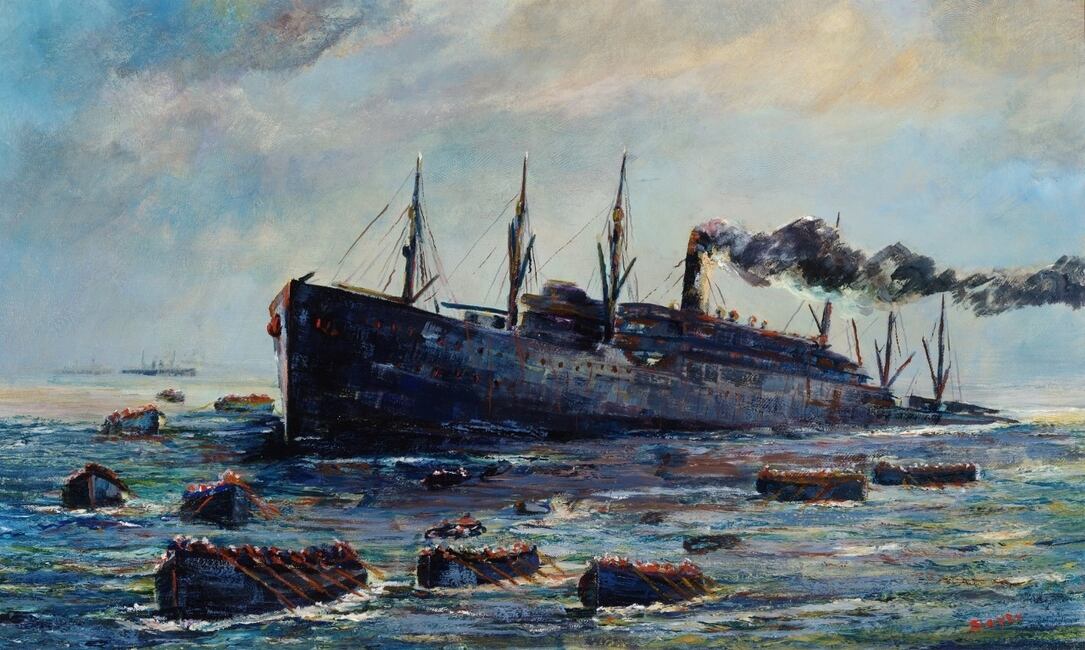

“It was a marvelous sight,” wrote a German destroyer officer. “All over the vast bay ships were in various stages of sinking.”

The handful of British boats and destroyers present steamed from one battleship to another, arbitrarily loosing small-arms fire in helpless frustration.

Markgraf‘s captain and nine German sailors were killed in the fusillade; 16 were wounded.

The British battleships, whose commander had learned of the scuttling, rushed back from maneuvers at 12:20 but could do nothing to stop 15 of the 16 German capital ships from going down.

Only Baden was beached and subsequently refloated.

The German crews took to lifeboats, from which they were picked up. Afterward they were placed on board the British battleships and were classified and treated as prisoners of war.

Of the once-proud German High Seas Fleet, a grand total of 52 out of 70 ships went to the bottom. Even today parts of the Imperial German Navy remain on the bottom of Scapa Flow, having defied all attempts to raise them.

The British press roared its contempt at what it regarded as a new act of perfidy by a treacherous enemy. To numerous German naval officers, Reuter had achieved a strange victory in defeat.

“I rejoice over the sinking of the German fleet in Scapa Flow,” wrote Adm. Scheer. “The stain of surrender has been wiped out from the escutcheon of the German Fleet. The sinking of the ships has proved that the spirit of the fleet is not dead. This last act is true of the best traditions of the German navy.”

Reuter’s gesture of defiance took some of the ignominy from the mutiny of 1918.

Both of those final acts of World War I, however, would be very much on the minds of the next generation of German admirals as they laid plans to redeem the High Seas Fleet’s honor under a new empire — the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler.

RELATED

This article was written by Mark T. Simmons and originally appeared in the June 1999 issue of Military History magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!