On June 18, 1812, the United States Congress declared war on Great Britain, initiating what some historians judge the final chapter of the American Revolution.

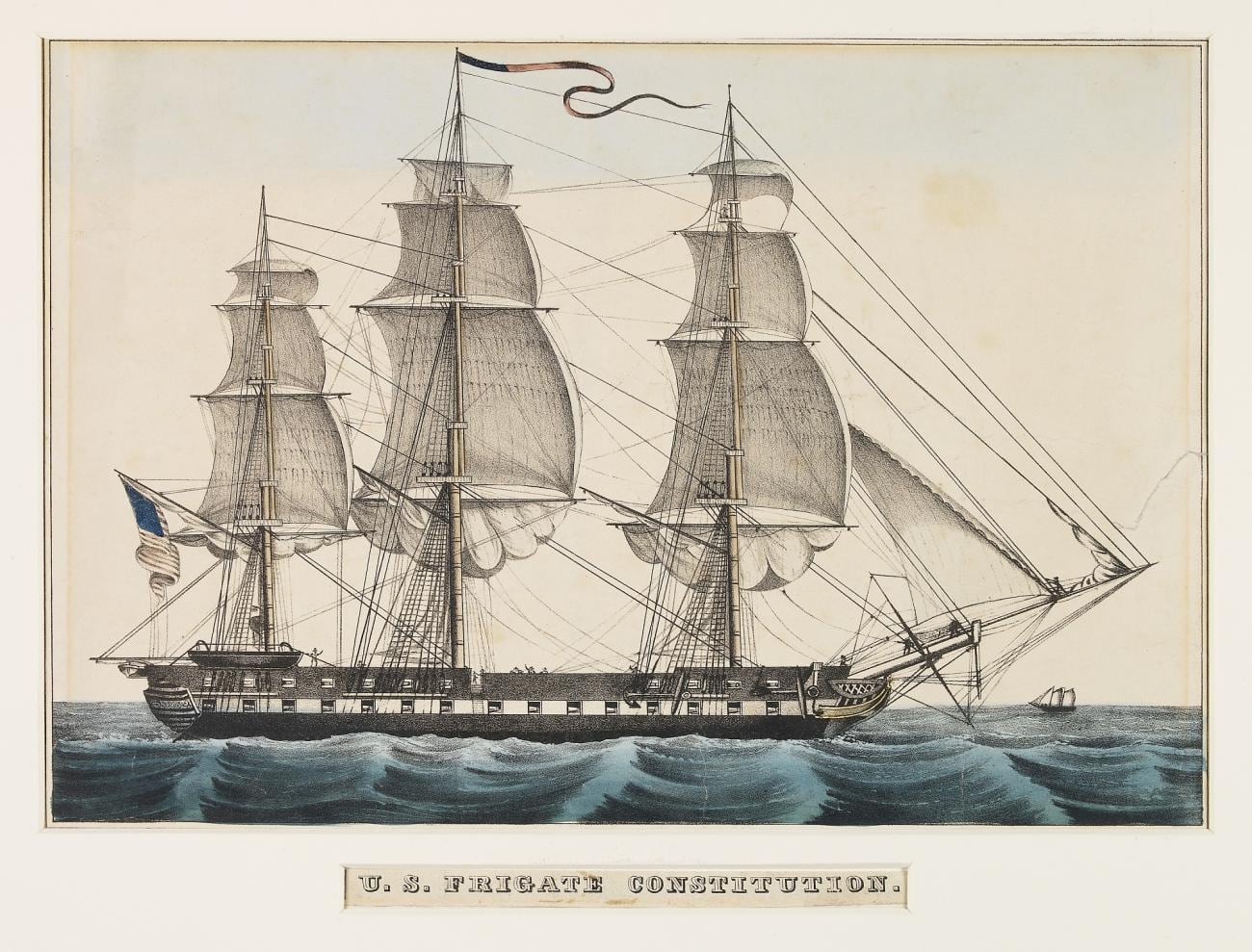

The War of 1812 was principally a naval conflict, based both on its causes and the key battles fought. It was in the oceanic blue water, on the Great Lakes, and in American coastal waters where the fledgling United States Navy boldly challenged Britain’s powerful Royal Navy to preserve the independence America had won in 1783 but which the new nation seemed at risk of losing in 1812.

But the war’s deadly sea duels fought between a daring band of American skippers and their more experienced Royal Navy commander opponents demonstrated that American officers and sailors could stand toe-to-toe with their British counterparts.

In the early 19th century, American merchants were caught in the middle of the long struggle between Great Britain and Napoleonic France.

U.S.-flagged ships were impounded by both sides for carrying supplies to the enemy, and American sailors were impressed by the British to man the Royal Navy’s global fleet of more than 600 ships.

When U.S. diplomatic efforts to ensure the right of neutral passage on the high seas failed, American President James Madison sent a June 1, 1812, message to Congress asking the legislative body to decide “whether the United States shall continue passive under these progressive usurpations, and these accumulated wrongs or, opposing force with force in defense of their national rights” should declare war.

Despite the small size of the Navy – partisan political squabbling had ensured that only a token number of U.S. ships were then in commission – and a woefully unprepared Army, Congress declared war and the nation plunged headfirst into a conflict with the greatest sea power of the age.

The U.S. Navy had only 16 ships in commission at the start of the War of 1812, while the Royal Navy had 85 vessels assigned to the North American and West Indies stations alone.

American debates about naval strategy centered on the question of concentration of force. Commodore John Rodgers, the senior captain in the service, lobbied for organizing U.S. warships into one squadron.

He believed doing so would force the Royal Navy to do the same, thus leaving large sections of the vulnerable American coastline free of predatory British cruisers.

After the declaration of war, Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton ordered Rodgers to cruise the Atlantic with a squadron composed of his flagship the frigate President, two other frigates and two smaller sloops of war. Rodgers departed from New York, while Capt. Isaac Hull, in command of the frigate Constitution, was dispatched from the Chesapeake Bay to join him.

EARLY ACTIONS

On news of the declaration of war and learning of Rodgers’ squadron sailing, the Royal Navy did indeed concentrate a squadron headed by the 64-gun ship of the line Africa leading four British frigates.

While searching for Rodgers’ squadron, the British found Hull’s Constitution before it could rendezvous with the other Americans. Africa and the frigates gave chase to overwhelm the single American ship.

Constitution raised all its canvas and ran. The pursuit lasted three days and nights. When the winds died, Capt. Hull ordered his boats into the water and the men pulled at their oars to drag the ship away from their pursuers.

In a masterful display of seamanship, Hull was able to escape the faster and more powerful British squadron by slipping away on the third night, and Constitution set sail for Boston to restock the drinking water pumped overboard to lighten the ship.

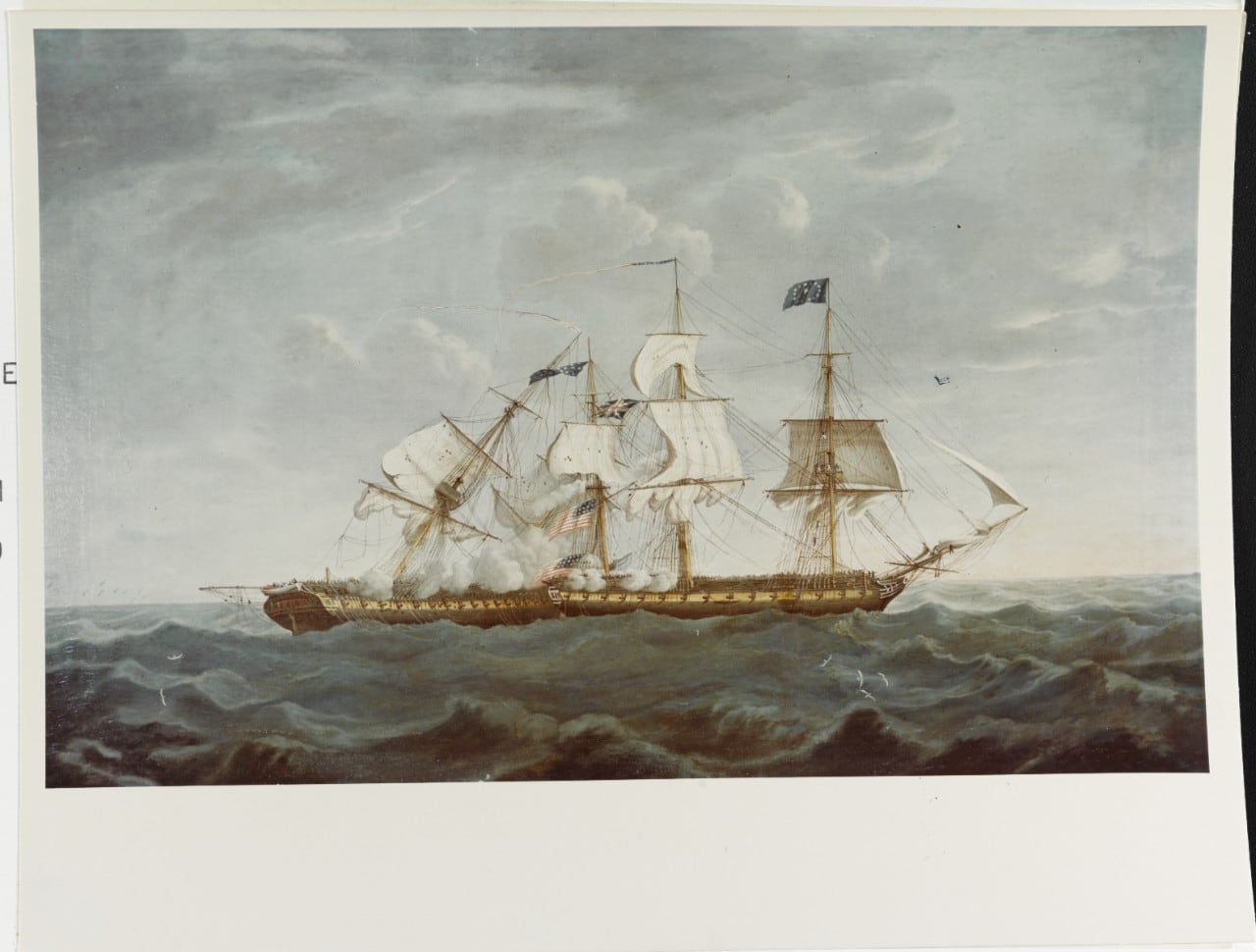

A month after the escape from the British squadron, Hull had Constitution back at sea sailing the northeast coast in search of British merchant ships to attack. On Aug. 19, 1812, Constitution’s lookouts spotted a large ship on the horizon and Hull, knowing his was likely the only American warship sailing alone, set off to investigate.

The ship was the British frigate Guerriere, commanded by Capt. James Dacres, and one of the frigates from the British squadron that had been dispatched to Halifax for repairs.

The captains of both vessels“beat to quarters,”and as crews manned the gun decks they shortened sail to better maneuver the ships at slower speeds. Guerriere ran with the wind while Constitution gave chase.

The British ship brought its guns to bear first, but the cannonballs did little damage – some even appeared to bounce off the sides of Constitution’s sturdy live oak planking.

Hull, carrying more sail than Dacres, caught Guerriere and delivered a perfectly timed broadside before surging ahead and cutting in front of the British ship. Fire from Constitution’s heavy guns dismasted Guerriere, while poorly aimed fire from the British ship caused little damage in return.

Without its sails and ability to maneuver, the British frigate fell defenseless and surrendered. As the sun set, the American crew treated the wounded and moved British prisoners by boat to Constitution.

Hull reported to Secretary Hamilton that “at daylight we found the enemy’s ship a perfect wreck,”and he ordered fires set in Guerriere’s storeroom to burn the ship before returning to Boston. As the victorious Americans sailed away, the fire reached the powder room and Guerriere exploded.

Constitution’s Aug. 19, 1812, victory was the one bright spot for the American cause during the first summer of the war.

Commodore Rodgers’ squadron cruise had resulted in little success, while Isaac Hull’s uncle, Brigadier Gen. William Hull, lost the Aug. 15-16 Battle of Detroit, in which he surrendered his entire American force on the Canadian border.

The failure of the U.S. invasion of Canada and of Rodgers’ squadron caused a reassessment of American plans. With Constitution’s stunning victory, however, doubts about American sailors’ ability to fight it out with the vaunted Royal Navy were brushed aside and the strategic question of how the U.S. Navy would deploy was answered.

American frigates began to cruise as single ships in search of British merchant vessels and lone enemy warships, confident that they could fight broadside to broadside with any comparable British ship.

Most of September was spent refitting and organizing U.S. Navy ships. In October they put to sea, and by month’s end the heavy frigate United States, under Capt. Stephen Decatur, was sailing the Atlantic between the Azores and Cape Verde Islands.

On Oct. 25, the watch spotted a sail on the horizon and the two vessels closed on each other. At 9 a.m. the battle began between United States and the British frigate Macedonian, one of the Royal Navy’s newest ships, as the opposing warships exchanged long-range fire.

Macedonian, carrying more long-range guns, managed a heavier fire than the Americans, but the poorly aimed British shots did little damage (Decatur ascribed it to the building seas).

Both ships then maneuvered to close the distance. An hour later the battle became close and United States, armed mainly with short-range but heavy carronades, unleashed a devastating fire on the British frigate.

Macedonian’s Capt. John Carden later reported to the British Admiralty: “I soon found the enemy’s force too superior to expect success.”

Decatur’s gunners blasted Macedonian’s rigging, splintering its masts, cutting away rigging and sails, and eliminating its ability to maneuver. The American fire dismounted many British cannon, and United States, with its canvas relatively unharmed, surged past Macedonian.

Decatur came about on his enemy’s bow and took position to rake the rival ship from stem to stern. Capt. Carden realized his ship was “a perfect wreck,” and as Decatur prepared to open fire again, Carden lowered his colors in surrender.

Soon, American newspapers celebrated the second great U.S. Navy victory in single-ship combat during the war’s first months.

Also in October, Constitution — now commanded by Capt. William Bainbridge and accompanied by the sloop of war Hornet — sailed from Boston, heading for the Cape Verde Islands. After cruising the eastern Atlantic with little success, Bainbridge headed southwest toward Brazil’s coast.

In Bahia the Americans discovered a British sloop of war at anchor, and Bainbridge ordered Hornet to blockade the port and wait for the ship to attempt to sail clear. He sailed Constitution south along the Brazilian coast, 30 miles from shore. Early on Dec. 29, lookouts spotted a pair of sails and Constitution approached the 38-gun British frigate Java, sailing with a captured American merchantman.

Bainbridge headed out to sea, away from the shoals to ensure open water for a battle, and Java gave chase. Over several hours, a running gun battle developed, each ship maneuvering for a raking shot at the opponent while trying to maintain enough distance to prevent being raked by enemy fire.

American gunners wreaked havoc on Java’s rigging, but British fire shot away Constitution’s wheel. An hour into the battle, the Americans managed to close and shot away Java’s foremast and the top of its mainmast. The wreckage fell on the British gun deck, fouling nearly the entire starboard battery.

As Java’s fire slackened, Constitution’s continued, shooting away much of Java’s standing and running rigging.

Two hours into the battle, as Java’s deck lay in shambles, British sailors struggled to clear the wreckage from their guns to continue the fight. Java’s Capt. Henry Lambert, however, fell mortally wounded and his first lieutenant, Henry Chads, took command of the ship.

Bainbridge, unable to see the British colors amid the wreckage, thought Java had struck its colors and hoisted Constitution’s canvas to shoot out ahead of the British ship. There, in relative safety, the Americans made repairs to Constitution while determining that Java had not yet surrendered.

After an hour of damage control, Bainbridge placed Constitution directly across Java’s bow, making ready to deliver a devastating broadside. But as Constitution prepared to fire, Lt. Chads realized the futility of continued resistance and struck his colors.

In six months of war, U.S. Navy frigates proved untouchable, decimating their British counterparts in three major sea battles that shattered the Royal Navy’s reputation of naval invincibility.

Adm. Sir John B. Warren, from his headquarters at Bermuda, wrote to Britain’s Admiralty Secretary requesting reinforcements. In his report, Warren stated that American frigates outmatched his vessels in size and strength, blaming British losses not on the U.S. Navy’s ability to fight but instead on its superior ships.

In a reversal of fortunes for a service that had contributed to the war’s cause through its policy of impressing American sailors, Warren also complained that British seamen were joining the U.S. Navy in large numbers after their capture by the Americans.

Finally, he listed the significant losses British merchant ships had suffered in the West Indies under the guns of American privateers. Warren therefore considered the forces he had under his command inadequate for the task of countering the American warships.

BLOCKADE AND REVERSAL

As 1813 began, the Royal Navy shifted its approach to the naval war with the United States.

Success in England’s conflict with Napoleonic France allowed the British to free more vessels, including several large, 74-gun ships of the line, for service on the American coast. Along with the reinforcements, the British Admiralty ordered Adm. Warren to institute a blockade of the major American ports.

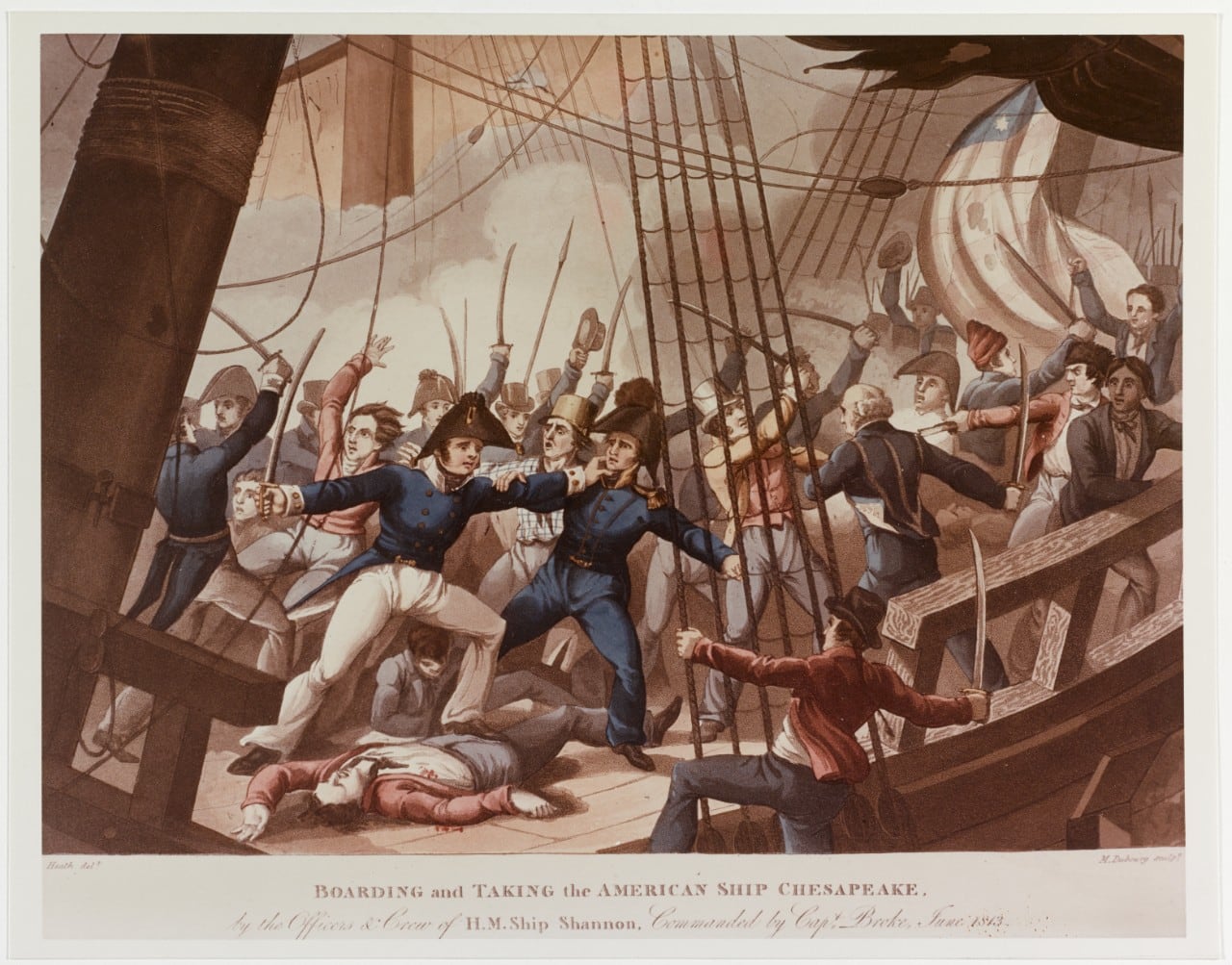

In May 1813, Capt. James Lawrence took command of the heavy frigate Chesapeake, refitting in Boston harbor.

Weeks before, he had returned to the United States after defeating the British sloop Peacock while commanding the sloop of war Hornet off the Brazilian coast.

As Lawrence worked to fit out his command, the British 38-gun frigate Shannon lay outside the harbor blockading the port. Shannon’s Capt. Philip Broke was nearing the end of his deployment and had drilled his crew for months. He sent Lawrence a letter challenging him to a single-ship duel.

Yet before the letter arrived, Chesapeake had sailed with its freshly refit but inexperienced crew.

On June 1, Shannon lay quietly outside the harbor waiting for Chesapeake to clear the shoals. Once the two ships had raised fighting sails and closed to within pistol shot, each ran up its colors. The battle began with the two frigates pouring cannon fire into each other.

After the ships exchanged three broadsides, Chesapeake drifted into Shannon and the two vessels became locked together with their rigging tangled and their guns muzzle to muzzle as the gunners continued to fire. The decks of both ships were littered with damage and bodies as the ships’ heavy cannon blasted away from point-blank range.

Lawrence fell with a mortal wound in the opening broadside and gave his famous final order to his lieutenants: “Don’t give up the ship!”

As the two frigates remained locked together in a horrific tangle of rigging and cannon fire, Capt. Broke gave the order to board the American ship. Shannon’s men surged aboard Chesapeake with cutlasses and pistols and fought their way across the decks as inexperienced Americans struggled to fend them off.

After 15 minutes of brutal hand-to-hand fighting, the British boarding party reached the American flag on the quarterdeck, hauled it down and ran up the Union Jack. The fight soon ended as the surviving Americans, recognizing they had been beaten, called for quarter.

With Chesapeake’s defeat, the British tightened their blockade. In June 1813, United States, the newly rechristened Macedonian and Hornet were in New York harbor under Decatur’s leadership.

Decatur attempted to slip through the blockade by sailing his ships south past Sandy Hook, New Jersey, but was turned away by heavy weather.

Looking for another escape route, Decatur sailed through Hell’s Gate into Long Island Sound, but there he faced an overwhelming British squadron.

Frustrated, the American ships sheltered in the harbor of New London, Connecticut, waiting for an opportunity to sail clear of the blockade.

By July 1813, news of the British blockade’s initial success and Shannon’s victory over Chesapeake had not yet reached Britain, while the Admiralty weathered a storm of criticism over the Royal Navy’s 1812 single-ship defeats at the hands of the American frigates.

The Admiralty, realizing the U.S. Navy was stronger than assumed, on July 10, 1813, issued orders to Royal Navy station commanders that British frigates were strictly forbidden to face their American counterparts in single-ship combat.

Capt. Broke’s daring challenge to Lawrence and subsequent victory over Chesapeake notwithstanding, the only way British warships could ensure they avoided defeat was by over-matching the dangerous American frigates with overwhelming numbers.

THE PACIFIC

Throughout the final months of 1812 and the beginning of 1813, Capt. David Porter sailed the U.S. frigate Essex through the Atlantic in search of British warships. After he left Delaware Bay later than scheduled, his orders were to join Commodore Bainbridge at sea to cruise in squadron with Constitution and Hornet.

But, first at the Cape Verde Islands, and then off the coast of Brazil, Essex failed to find the other American ships. As Constitution headed back to the United States after its victory over Java, and Hornet returned after defeating Peacock, Porter invoked a short passage in his orders stating that, should he be unable to rendezvous with the squadron, he should continue as he saw fit and act “in the good of the service.”

At the beginning of 1813 off Brazil’s southern coast, Porter surprised everyone by turning Essex south, setting sail for Cape Horn and the Pacific Ocean.

In March 1813, after two months at sea, Essex sailed into the Pacific port of Valparaiso, Chile. Porter quickly set about provisioning his ship before word could spread to the unprotected British Pacific whaling fleets.

Essex reached the Galapagos Islands in mid-April and set upon the vulnerable, unsuspecting whalers. Between April and October the Americans captured 12 prize ships.

Using supplies from captured ships and food available from the sea turtles, birds and iguanas of the islands, Essex and its men remained at sea for a remarkably long and productive time – Porter estimated that Essex’s attacks on the whaling fleet cost Britain $5 million.

Essex spent fall 1813 in the Marquesas, where Porter refitted his frigate and four prizes that sailed with him as a squadron. While the American ships were in the islands, the British frigate Phoebe, under Capt. James Hillyar, arrived in the Pacific.

Hillyar’s secret orders were to sail for the American Pacific Northwest to “destroy, and if possible totally annihilate any settlements which the Americans may have formed.”

He arrived in the Pacific thinking his would be the only warship in that ocean, but instead he discovered Essex had been ravaging British interests. Hillyar elected to deviate from his orders. Taking along the sloop Cherub, he sailed for the whaling grounds.

In December, Porter finished Essex’s refit as well as refitting a captured whaler, which he armed, renamed Essex Junior, and placed under the command of Lt. John Downes. While in the Marquesas, Porter had learned the British had sent warships searching for him, and with refreshed crews and refitted ships he set sail to find and attack the enemy.

On Jan. 12, 1814, Essex and Essex Junior arrived and anchored in Valparaiso harbor. Three weeks later, the Americans spotted sails on the horizon and Phoebe and Cherub sailed within view.

Chile was a neutral power in the war between America and Britain, and custom and treaty ensured the two nations would not bring their conflict into neutral harbors. As Hillyar entered the harbor, he brought Phoebe toward Essex, sailing close enough to speak with Porter and enquire about his health as they drifted past.

Porter saw the British warship’s decks cleared for action but kept his own men on the defensive – neither ship acted. Phoebe sailed past Essex and anchored.

The next morning Essex raised a flag that read: “Sailors Rights and Free Trade.” Phoebe reciprocated with its own flag: “God & Country, British Sailors Best Rights, Traitors Offend Both.” Essex manned the rigging and the American sailors gave out a hearty cheer, which the British ships returned. Despite the taunting, both sides respected the harbor’s neutrality and restrained themselves.

After several days in port, Hillyar sailed his ships clear of the harbor and established blockading positions. Porter was confident in the superior sailing ability of his frigate, especially with his seasoned crew, and was convinced he could sail clear of the blockade. Essex Junior, however, was inferior to Cherub and had little chance of escape. Porter remained in Valparaiso harbor in an attempt to provoke Hillyar into single-ship combat. Several times Essex got under way but never cleared the harbor. On March 9, a message from the “Crew of Essex” passed to the “Crew of Phoebe” challenging them to send Cherub away and fight ship to ship. Hillyar, unwilling to give away his firepower advantage, declined.

Porter made preparations to depart the harbor, fearing more British warships might arrive. On March 18, weather forced Porter’s decision as strong winds caused Essex to begin dragging anchor.

Porter cut the anchor cable and set sail. He hoped to use the strong winds to his advantage; but once under sail, Essex’s mast broke, sending sails and rigging crashing to the deck. Porter sailed back close to shore and anchored again. Although the Americans believed they were still under protection of the neutral harbor, when Hillyar saw them clear Valparaiso’s inner harbor, he considered them open for attack.

At first the British used their advantage in long guns and fired from a distance Essex could not reach. However, the cannon fire had little effect and Hillyar was forced to bring his ships closer.

Porter slipped his anchor again, and after an hour of occasional firing and maneuvering by the British, the two frigates began what Hillyar described as “a serious conflict.” For nearly an hour the two ships exchanged broadsides. The British were able to maneuver both Phoebe and Cherub onto the Americans’ stern and commenced a devastating raking fire the length of the deck.

Porter’s men struggled to re-position their cannon out of stern ports and commenced a return fire that caused the British to maneuver again.

Phoebe and Cherub moved to Essex’s starboard quarter, a vulnerable blind spot where neither the Americans’ heavy carronades nor the stern guns could fire.

Porter wrote that “the slaughter onboard [his] ship had now become horrible.” His men continued to fire the heavy carronades, but with little impact as the British moved away to engage with their long guns. As his ship filled with wounded and his men struggled to fight the fires aboard, Porter “gave the painful order to strike the colors.”

THE FRIGATE WAR

The War of 1812 ended in a draw, with very little accomplished by either combatant. Although the British had invaded and burned the American capitol, they had little to show for their achievement beyond symbolism. The United States Army failed repeatedly in Canada and had barely managed to maintain American borders in a war America had declared. The U.S. Navy had been the one bright spot in an otherwise uninspiring war for the Americans. America’s naval War of 1812 on the high seas was more successful as frigate captains dueled each other, but victories were won by both sides.

Notably, however, the officers and sailors of the U.S. Navy – led by a determined and intrepid band of frigate captains – demonstrated that the Royal Navy’s“invincibility” was a myth, and“the Frigate War” raised the standing of the still independent young nation.

RELATED

Cmdr. Benjamin “BJ” Armstrong is a career U.S. Navy helicopter pilot. His works include 21st Century Mahan: Sound Military Conclusions for a Modern Era. Armed with a doctorate from King’s College London, he’s also an assistant professor in war studies and naval history at the U.S. Naval Academy. This article originally appeared in the January 2013 edition of Armchair General, on Historynet.com, a sister outlet of Navy Times.

Editor’s note: this story has been updated to reflect the correct name of Capt. James Lawrence.