During the winter and spring of 1863, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had tried every trick in the book to get his army across the Mississippi River to attack the Confederate fortress of Vicksburg. All had failed, and his soldiers languished in the fever-ridden swamps on the “wrong” side of the river.

He had recently sent a 10,000-man infantry division in 25 steam transport ships guarded by several powerful ironclads on a circuitous 400-mile route through the back bayous, rivers and swamps, hoping to catch the Rebels off-guard above the city. This was known as the “Yazoo Pass Expedition.”

It had been driven back, however, though Grant did not know it yet.

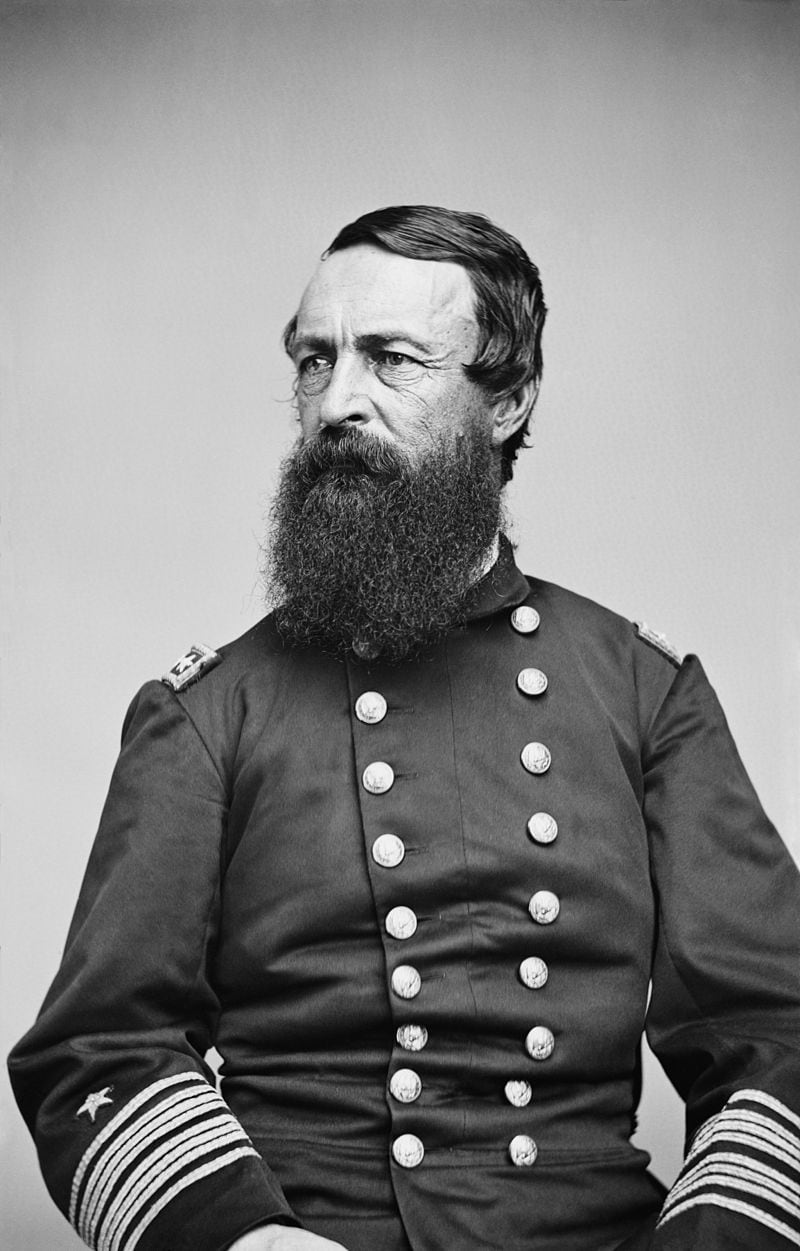

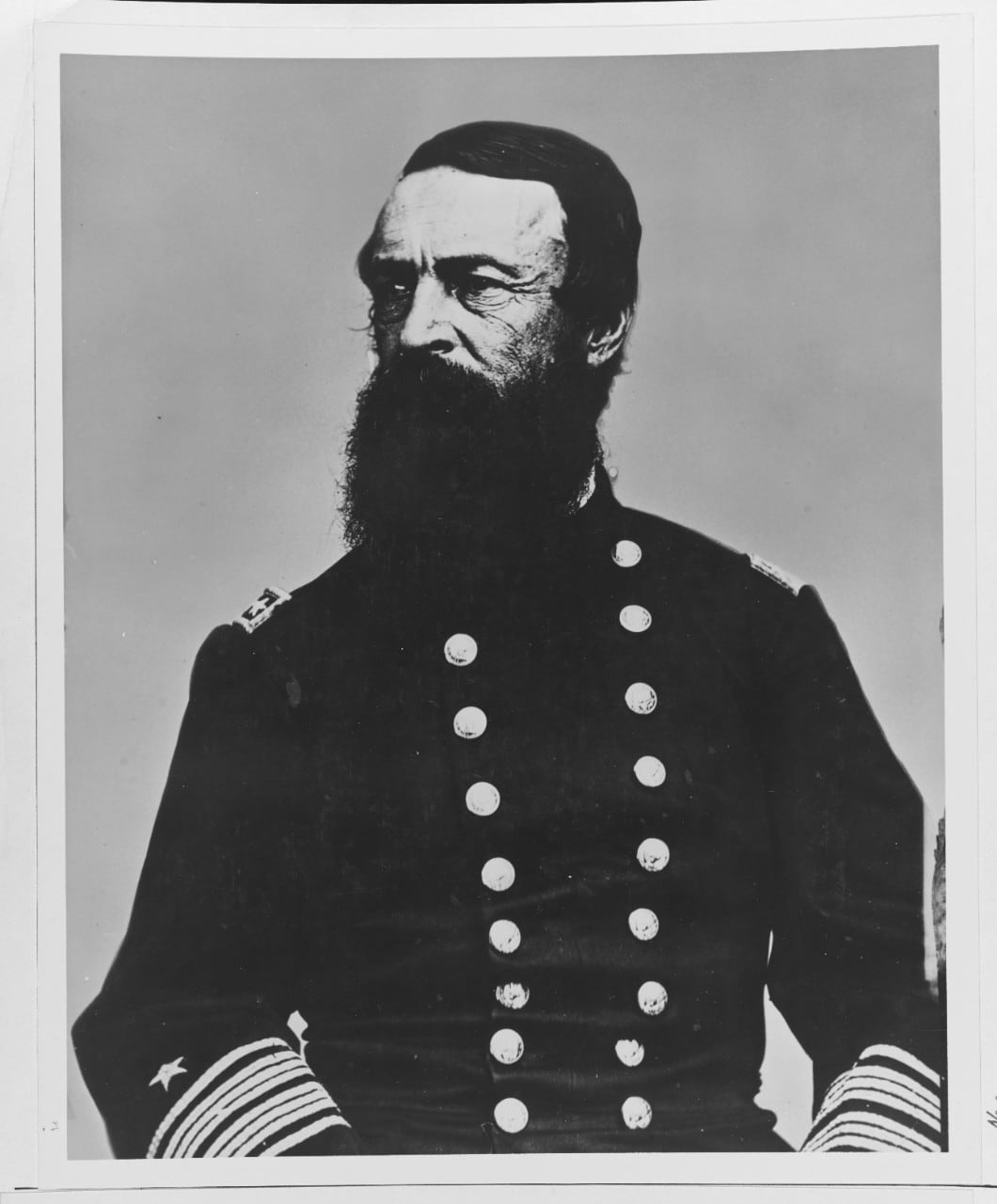

But Acting Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter, the U.S. Navy commander on the scene, came up with yet another scheme to surprise the Rebels in their own backyard.

In order to get the Yazoo Pass Expedition out of the Mississippi and into its backwaters route, it had been necessary to blow up a levee some 200 miles north of Vicksburg and this, in turn, had flooded the entire countryside for hundreds of square miles.

Porter smelled an opportunity.

It was now the middle of March, and Grant, as yet uncertain about the fate of the thousands of men he had sent down the Yazoo Pass, found himself “much exercised for [their] safety.”

Being a man of action, Grant decided to see for himself if there was another way to prevail, for Rear Adm. Porter had come up with his own bizarre proposal for attacking Vicksburg from the rear.

It involved yet another amphibious expedition that would take advantage of the now flooded bayous and rivers that the rear admiral asserted would not only get the troops above the Confederate batteries at Haines’ Bluff, but get them past the Rebel guns of Fort Pemberton as well.

The scheme was to steam into the Yazoo River to an obscure stream opposite Vicksburg called Steele’s Bayou, then follow it north, away from the city, through Cypress Lake, Black Bayou, Deer Creek to the Rolling Fork where, a hundred miles later, they would then turn southward again into the Sunflower River for another hundred miles back down to the Yazoo.

It was a tortuous loop of 200 miles, but it left Fort Pemberton about 30 miles to the east, before reentering the Yazoo 20 miles above the Confederate batteries at Snyder’s, Drury’s and Haines’ Bluffs.

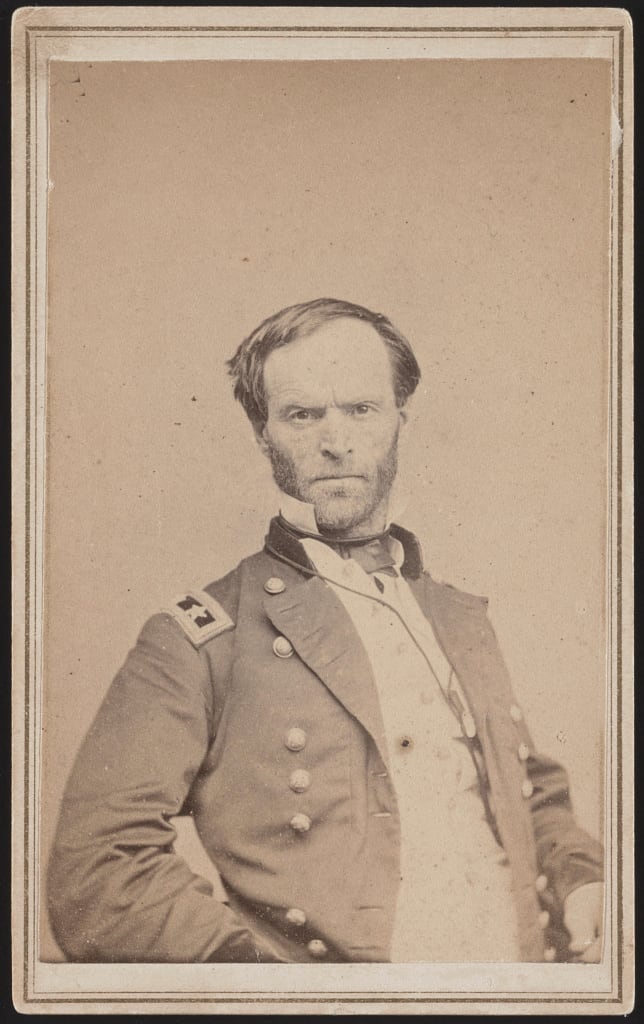

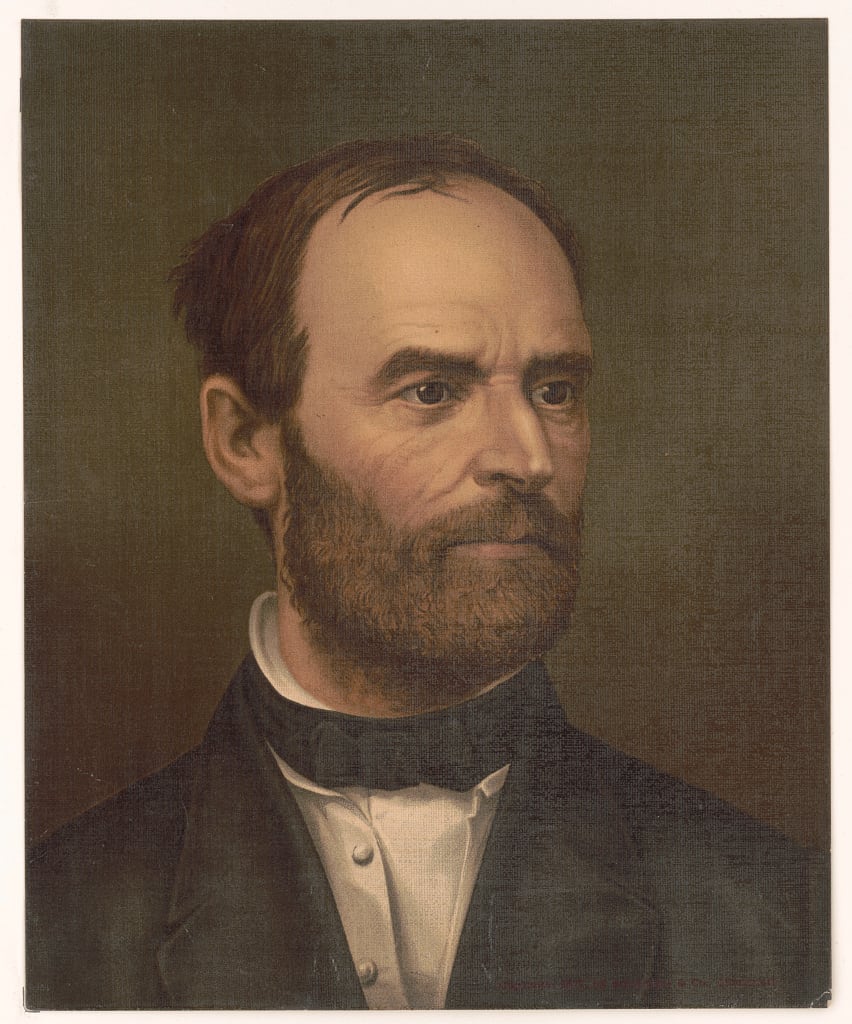

As luck would have it, Major Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman himself got tapped for the duty, along with one of his divisions, and on March 16 he embarked 7,000 infantrymen on transports that were to follow close behind the van, which consisted of five ironclads, four mortar boats and four tugboats, commanded by Porter himself.

They had no sooner shoved off than things began to go awry.

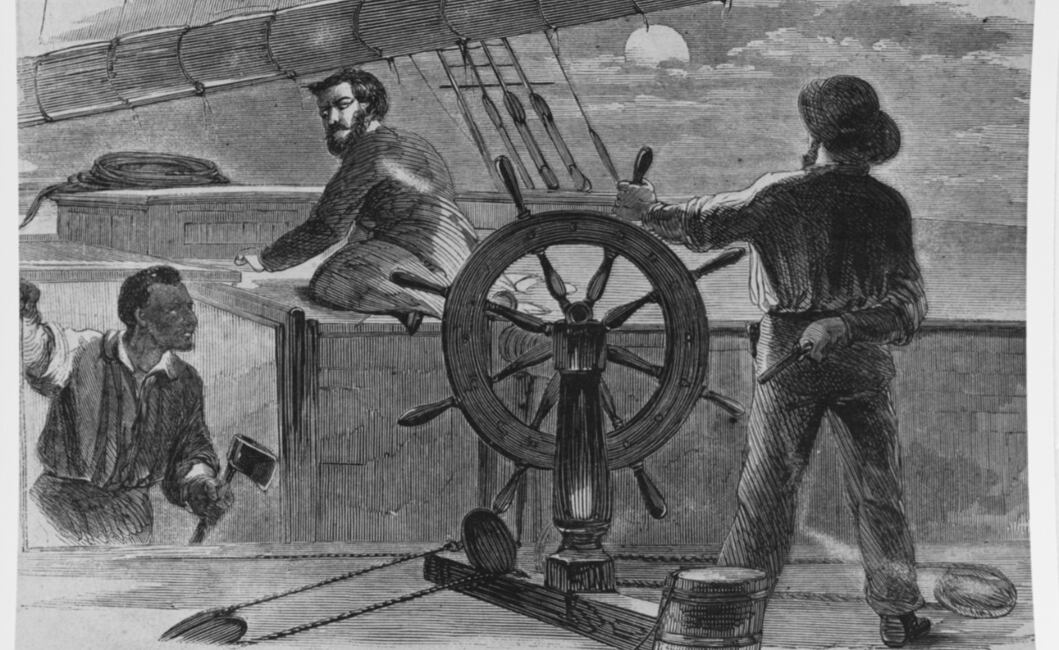

Surely it was one of the strangest wartime expeditions in naval history. Because of the levee break, the water was so high that in many places the big ironclads sometimes found themselves steaming above drowned roads and houses and even entire forests, with only the very tops of their trees showing.

Keeping in the channel became a major project. The ironclads drew 7 feet of water, whereas in normal times, according to Porter, these streams “did not contain enough water to float a canoe.” But the flood had put 15 feet under them, provided they did not sail off into an underwater hill or vale.

Almost immediately, another problem presented itself, similar to the one encountered by the Yazoo Pass Expedition — only worse.

The twisting narrowness of the streams and the rise in water level often put the boats right in the path of overhanging trees and limbs that, when struck, carried away almost everything on deck, especially on the river steamers with their tall smokestacks, elevated pilothouses and ponderous loading tackle.

Not only that, but the trees and branches were inhabited by all species of swamp creatures that had sought refuge from the flood. Whenever a boat crashed or bumped into one of these natural obstacles, its decks were immediately inundated with a perfect shower of live zoological specimens: ’coons, possums, snakes of all descriptions and temperaments, rats, mice, cockroaches, lizards, squirrels, wildcats, and a host of insects so varied and plentiful that their identification could only be guessed at.

Sailors manned brooms to sweep these startled visitors overboard, but some refused to go, which made life aboard ship more interesting.

After a few days, Sherman’s flotilla began to look like a moving shipwreck; most smokestacks had been torn off the transport boats, or bent beyond use. Wheelhouses, booms, ships’ boats, masts, sometimes entire superstructures had been demolished, and whenever the steamers hit a dead or damaged limb, it would come crashing straight to the deck, smashing skylights and framework, adding to the chaos.

As with the Yazoo Pass Expedition, smoke from burning cotton billowed from whatever high ground there was, and often obscured navigation. Porter was appalled by the “wicked[ness]” of such wanton destruction, and shouted to a grizzled old overseer, “Why did those fools set fire to that cotton?”

“Because they didn’t want you fools to have it,” was the equally discourteous reply.

At one point, pyres that blazed along Cypress Bayou actually threatened to roast Porter’s gunboat crews alive.

As he described it, the bayou “was exactly 46 feet wide. My vessel was 42 feet wide.” On both sides of the stream some 6,000 bales of Confederate cotton were aflame. After learning from a slave that the cotton would burn for two or three more days, Porter was determined to push through.

“All the ports were shut in and the crews called to fire quarters, standing ready with fire-buckets,” he said.

A tugboat that was in the lead disappeared into the inferno after soaking everything down and when it emerged on the other side, all the paint was blistered and many of the crew singed.

On the deck of Cincinnati, Porter was forced to jump into a small iron-plated closet, followed by the captain, to keep from getting scorched, while the helmsman “covered himself with an old [wet] flag that lay in the wheelhouse.”

“Just after we passed through the fire,” Porter reported, “there was a terrible crash, which some thought was an earthquake. We had run into and quite through a span of bridge about fifty feet long, and demolished the whole fabric, having failed to see it in the smoke.”

And that was just the beginning.

Cypress Bayou was so crooked, Porter said, “At one time the vessels would all be steaming on different courses. One would be standing north, another south, another east, and another west through the woods. The tugs and mortar-boats seemed to be mixed up in the most marvelous manner.”

It was also filled with huge soggy logs with their ends pointing upward, “presenting the appearance of chevaux-de-frise, over which we could no more pass than we could fly.”

All this had to be cleared by hand, and no sooner had it been done than they heard the sinister racket of chopping from the dismal swamps ahead.

The ironclads, which had no tall masts or booms, managed to weather the damage better than the transports, and as a result Sherman and his infantry fell farther and farther behind the armored van.

By March 20, Porter’s naval force had reached the head of the Rolling Fork, the pass that would take them into the wide and deep Sunflower River. From there, the sailing promised to be fast and smooth all the way back down to the Yazoo River and victory.

But just then a combination of bad luck, misapprehension and Rebel ingenuity brought the operation up short.

Right at the entrance to the Rolling Fork was a small collection of houses, and along the banks a number of slaves stood watching the gunboats as they gathered to enter the pass.

Suddenly Porter looked out over his bridge and saw “a large green patch extending all the way across. It looked like the green scum on ponds,” he wrote in his memoir.

When he asked the slaves what it was, one of them replied that it was willows, which they weaved into baskets. The slave thought he might be able to navigate through it like an eel.

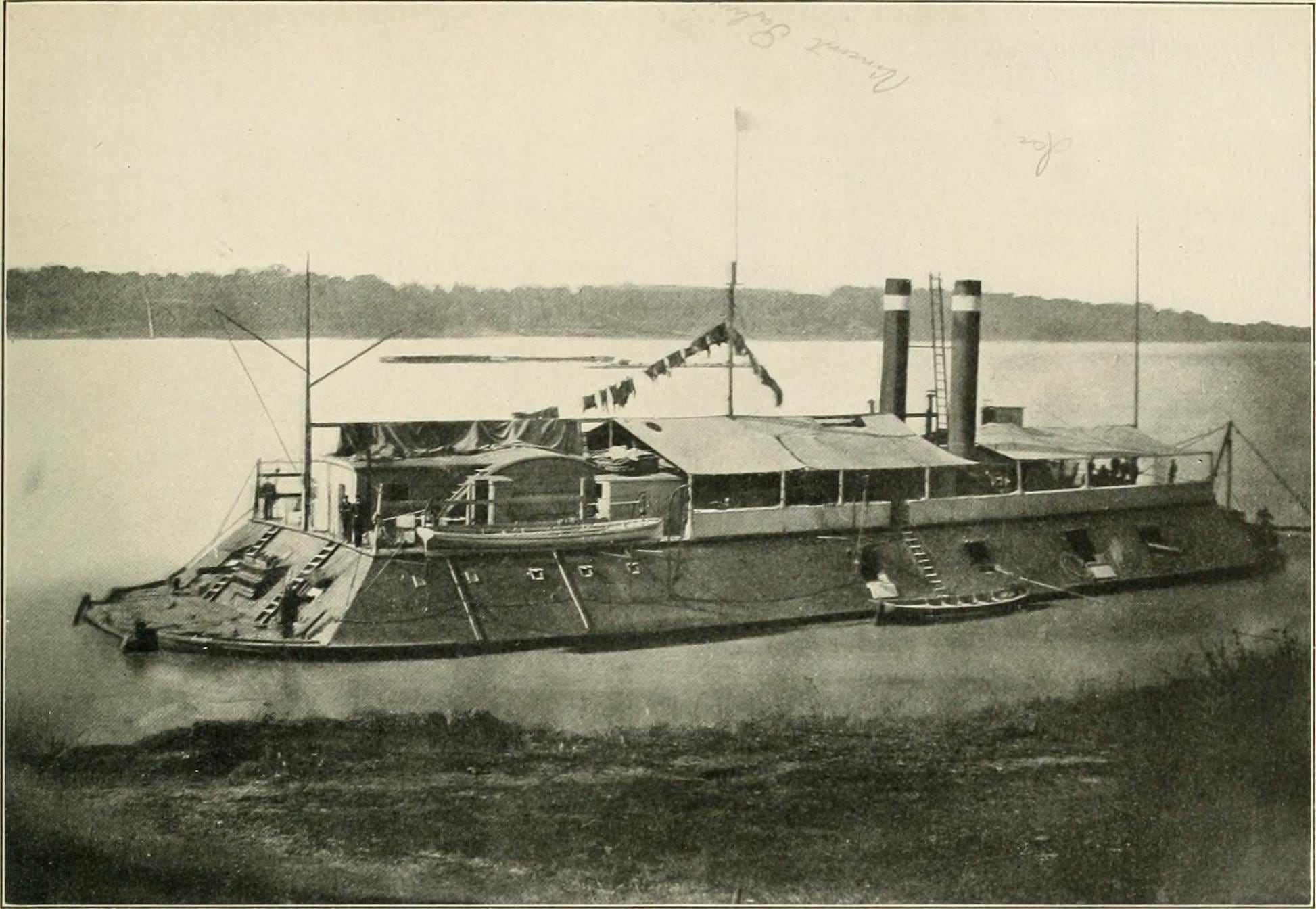

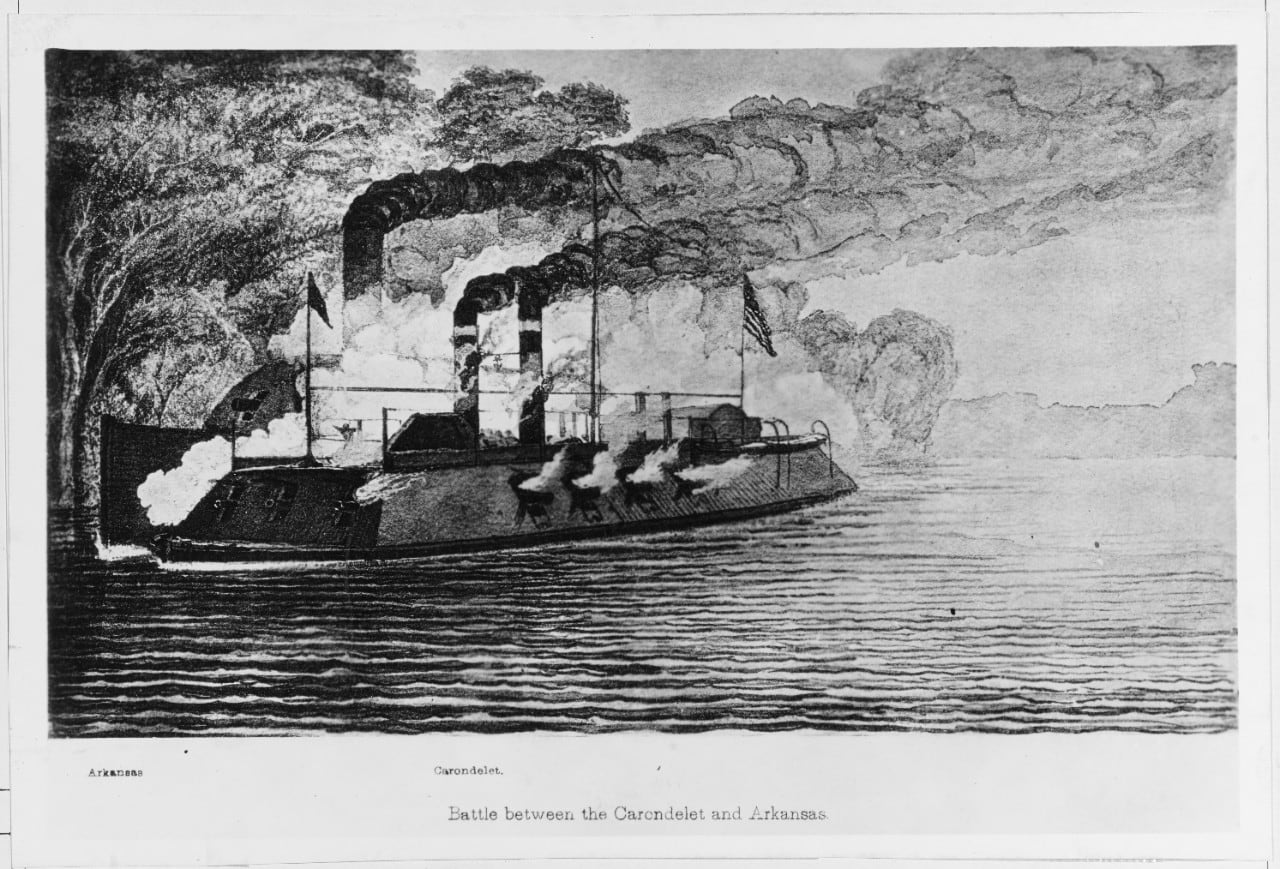

It was not so. As Porter’s new flagship Carondelet entered the strange patch of vegetation “full-steam-ahead,” it first slowed abruptly, and then came to a complete halt.

“The little withes caught in the rough iron ends of the overhangs and held us as if in a vice,” Porter reported. “I tried to back out, but t’was no use. We could not move an inch, no matter how much steam we put on.”

The men brought out large hooks and tried to snag off the willow branches to no avail. Porter looked to the banks for the man who had originally advised him about the willows and received a sobering reassessment — the willows were tougher than ropes.

Presently the crew produced “saws, knives, cutlasses and chisels” and went over the side, but soon as the little willow switches were cut away, “others sprang up from under the water and took a fresher grip on us, so we were worse off than ever.”

And even that was wishful thinking.

Suddenly from ahead came a boom of artillery fire, along with the chilling “crack” of a Whitworth rifled gun (possibly the same one that had helped thwart the Federal armada at Fort Pemberton during the Yazoo Pass Expedition) which had a dead-on accurate range of more than a mile.

Earlier, as the flotilla was waiting for the other ironclads to catch up, a Lt. Murphy, who commanded one of Porter’s boats, pointed out that there was an old Indian mound ahead, and that it might be a good idea to fortify it with several artillery pieces — just in case — while they were waiting.

Porter agreed, wondering why, if it was such a desirable strong point, the Confederates had not occupied it themselves.

It must have been because they thought it worthless,” he recalled thinking. “They showed themselves to be poor judges in such matters.”

As Rebel shells began bursting all about them, Porter quickly came to appreciate why the enemy hadn’t occupied the Indian mound — it was indefensible.

“Suddenly I saw the sides of the mound crowded with officers and men. They were tumbling down as best they could; the guns were tumbled ahead of them. There was a regular stampede,” he said.

Just as he was taking that in, scores of Rebel sharpshooters abruptly opened up on them from the swamps, behind trees, stumps and hummocks and worse — if such a thing was possible — “We could not use our large guns; they were way below the banks, and lying so close to it that we could not get elevation enough to fire over.”

Porter was in a fix for sure. His boats were stuck fast in the willows and surrounded by enemy sharpshooters, who made any attempt to free them up suicidal; he was powerless to return fire, and Sherman’s infantry, his only salvation at this point, was somewhere back down Deer Creek, oblivious to his predicament.

For all Porter knew, there may have been Confederates behind him as well as ahead and on both sides, and if they could obstruct the creek, and keep his crews pinned down inside the boats, then a boarding attack was probably imminent. A shiver of fear must have run over him when he realized what would happen if the Rebels actually seized his ironclads — in a nutshell, the whole face of the war on the Mississippi would instantly be changed.

But Porter was determined that would not happen on his watch and took measures to prevent it.

First, even if he could not elevate his own guns, the four mortar boats he’d brought along had no such problem, and he immediately set them into action lobbing their big 13-inch shells. It took a while to get the range, but finally the mortars managed to silence the Rebel batteries — at least temporarily.

Next Porter sent out riflemen of his own to try to deal with the sharpshooters, and when their fire had slackened — also temporarily — he “set to work again to overcome the willows.”

As the gunfire stopped, the slaves again began to gather on the bank and one of them overheard Porter grumble to himself, “Why don’t Sherman come on? I’d give ten dollars to get a telegram to him.”

One of the slaves, “Tub,” replied that he’d take the message to the general for a half-dollar.

With nothing much to lose at that point, Porter handed him the half dollar and scribbled out a message: “Dear Sherman: Hurry up for heaven’s sake…,” which Tub tucked into his hair, and then vanished into the swamps.

No sooner had this hopeful measure been set into motion than word reached Porter that Rebel steamers were in the process of debarking some 2,000 troops at a landing up ahead.

As if to emphasize how unpromising the situation had become, the Confederate artillery opened up on them again from a different location.

RELATED

As night came on, Porter was constrained to issue a general order steeped in gloom: “Every man and officer must be kept below, ports kept down, and guns loaded with grape and canister and only fired when an attempt is made to board us or rush upon us. Put all hands on half rations. No lights at night. Men to sleep at the guns….Every precaution must be taken to defend the vessels to the last, and when we can do no better we will blow them up…”

But then, right at sundown, Providence smiled on Rear Adm. Porter and his beleaguered flotilla. The crews suddenly began to notice that the water in Rolling Fork “had begun to run rapidly, and large logs began to come in, and pile up on the outside of the willows.”

The water continued to rush in almost like a rising tide — although they were hundreds of miles from the ocean — and soon began to lift the boats free of the accursed willows. It was, Porter realized afterward, the torrent from the second levee that Brig. Gen. Isaac Quinby of the Yazoo Pass Expedition had blown up a day or so earlier in hopes of flooding out Fort Pemberton.

Somehow the wall of water did not reach that place, but it did pile up enough under the Yankee boats in Rolling Fork and Deer Creek for Porter to give the order to ship all rudders, and try to back out down into the fraternal embrace of Sherman’s 7,000 infantrymen. As an added bonus, the new flood lifted the ironclads high enough to employ their big guns against their Rebel tormentors in the swamps.

Sherman, however, knew nothing of this when the telegrapher, Tub, found him late that night and handed him Porter’s note, which he had thoughtfully concealed in a cigar wrapper.

“The admiral stated,” Sherman recalled, “that he had met a force of infantry and artillery which gave him great trouble by killing the men who had to expose themselves outside the armor to shove off the bows of the boats, which had so little headway that they would not steer. He begged me to come to his rescue as quickly as possible.”

Immediately Sherman dragooned a regiment of Missouri infantrymen and sent them forward down a swampy river road, then set off himself in a canoe after more reinforcements, which were farther back down the river.

Presently he located a brigade on a steamer and off they went to Porter’s rescue, “crashing through trees, carrying away the pilot-house, smoke-stacks, every thing above deck, but the captain was a brave fellow, and realized the necessity,” Sherman wrote.

“The night was absolutely black, and we could only make about two and a half of the four miles. We then disembarked, and marched through the canebrake, carrying lighted candles in our hands.”

After this Druid-like procession had slogged until nearly dawn, Sherman rested the men in a plantation field, and at daylight began marching again toward the sound of Porter’s guns, which they could now hear distinctly in the distance and which, Sherman remembered, told him that “time was precious.”

Still they waded through miserable mires where “the smaller drummer boys had to carry their drums on their heads,” and by noon had actually come 21 miles, when they met up with a detachment of the Missouri troops Sherman had sent earlier.

Porter had ordered these men back downriver to prevent the Confederates from blocking his gunboats in from behind, and not a moment too soon, for the Rebels were already at work with their axes, chopping down trees on the banks to obstruct his escape. Finally Sherman and his soldiers came in sight of the big ironclads, which the rising tide had lifted enough to “occasionally [fire] a heavy eight-inch gun across the cotton fields into the swamp behind.”

Somewhere along the way, Sherman had acquired an old horse that he rode bareback with a rope bridle, and when he approached the stricken gunboats the sailors came out and cheered him “most vociferously,” as his bluecoats “swept forward across the cotton-field in full view.”

When Sherman found Porter, “He was on one of his ironclads, with a shield made from a section of a smokestack, and I doubt if he was ever more glad to meet a friend than he was to see me. I inquired of Adm. Porter what he proposed to do, and he said he wanted to get out of that scrape as quickly as possible.”

It was now March 21, five days after the invasion force had entered Steele’s Bayou; now the boats and men were backing out single file, thwarted, rudderless, dejected, caroming off the banks in place of steerage, and with Vicksburg no closer to capture than it was when they first arrived there in December.

Grant eventually did cross the river and take Vicksburg, in a series of deadly battles that ended in a terrible siege. With it, he took control of the river and the entire Mississippi River Valley as well, severing the Confederacy in two; all on the same day — ironically, the Fourth of July, 1863 — that Rebel Gen. Robert E. Lee began his long retreat from Gettysburg.

These two events, a thousand miles apart, were the death knell for the Southern Confederacy, but her politicians refused to concede and fought on for nearly two more bloody years.

“Vicksburg should have ended the war,” Sherman later observed, “but the Rebel leaders were mad.”

Best-selling author Winston Groom has written 15 books and was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 as coauthor of Conversations With the Enemy. This article was excerpted from his new book, Vicksburg 1863 (Alfred A. Knopf, April 2009). Originally published in the July 2009 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.