During World War II, United States military restrictions prohibited American servicemen from keeping personal journals. Those who did, such as marine Eugene B. Sledge, author of With the Old Breed, and sailor James J. Fahey, who wrote Pacific War Diary, 1942–1945, hid their notes in Bibles or similar personal effects.

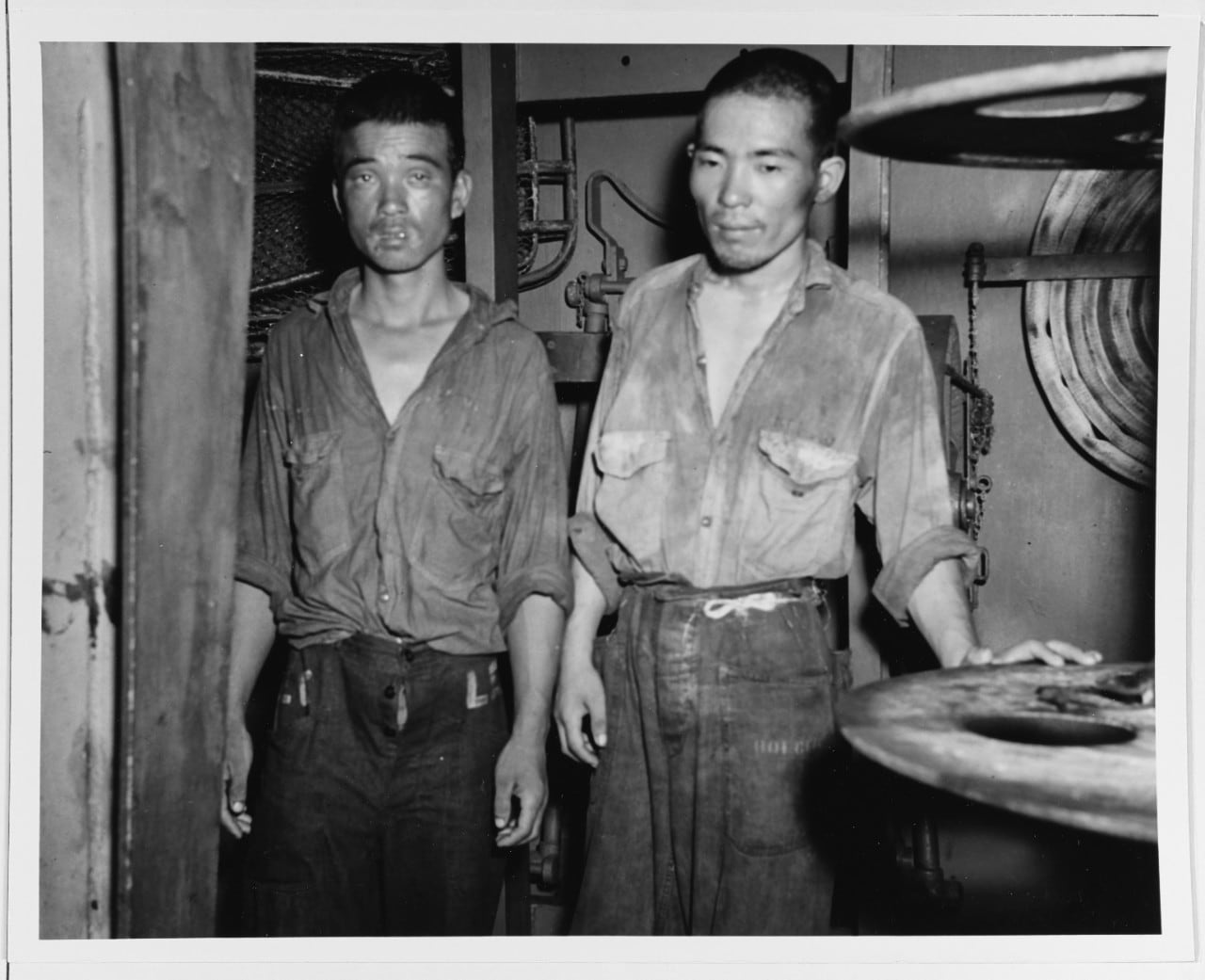

Japan’s military evidently had no such restriction, and Allied forces during their advance across the Pacific found many Japanese diaries, which often provided rich intelligence.

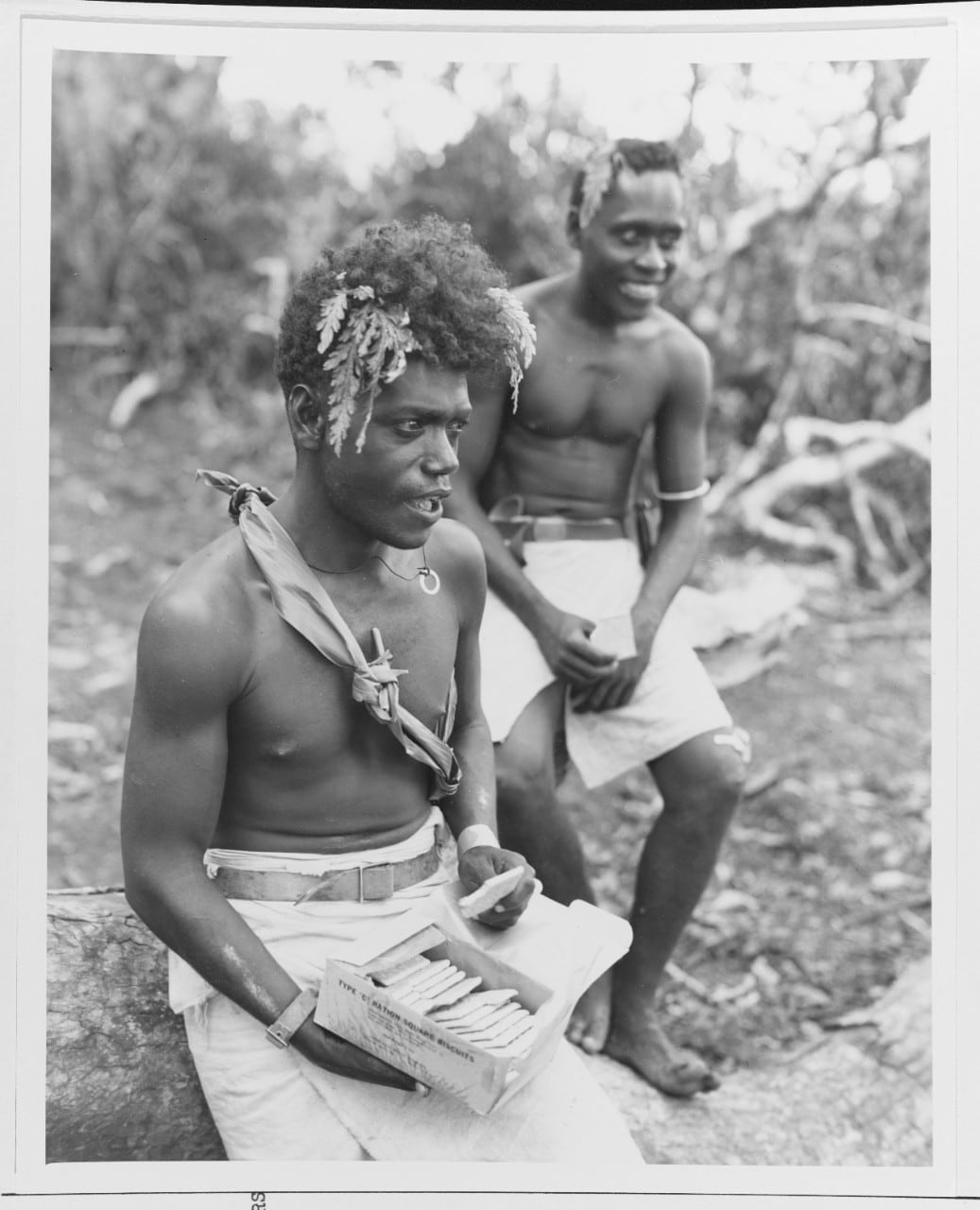

What follows are excerpts from the diary of Probational Officer Toshihiro Oura, who was posted near the Munda Point airfield on the southwest tip of New Georgia. His journal was translated in 1943 by Dye Ogata and Frank Sanwo, nisei interpreters with the intelligence section of the U.S. Army’s 37th Infantry Division.

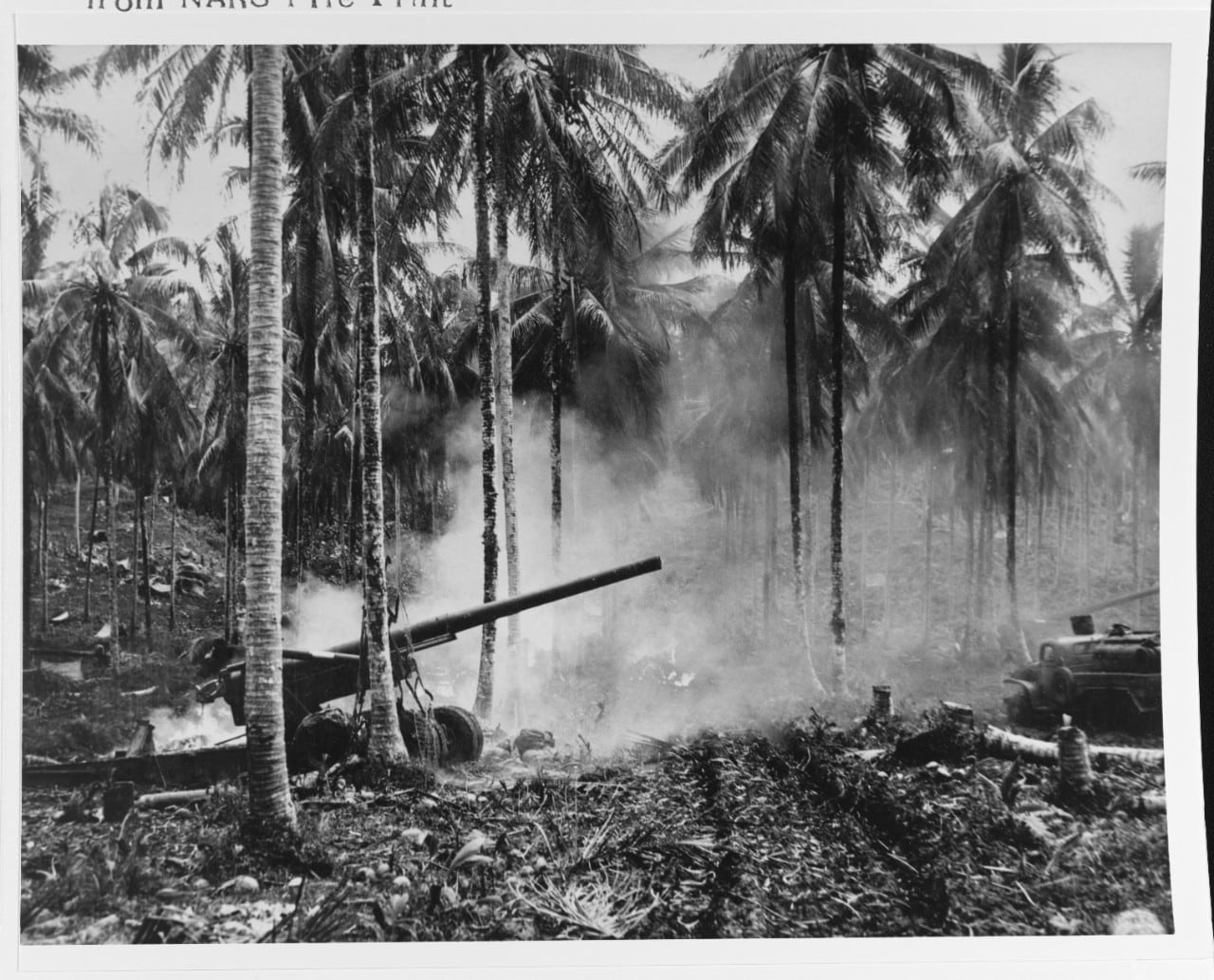

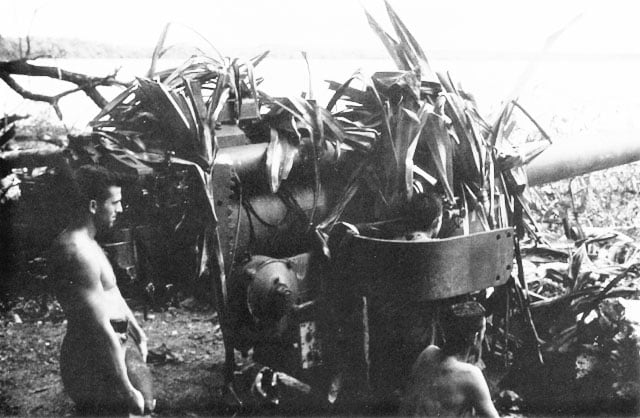

Oura was a platoon leader in the Imperial Japanese Army’s 15th Antiaircraft Field Defense Unit, which was commanded by Col. Shunichi Shiroto. It was equipped with 25mm and 40mm antiaircraft and antitank automatic cannons.

In June 1943, about five months after America’s final victory at Guadalcanal, U.S. forces continued their advance through the Solomon Islands by commencing operations against Japanese-held New Georgia.

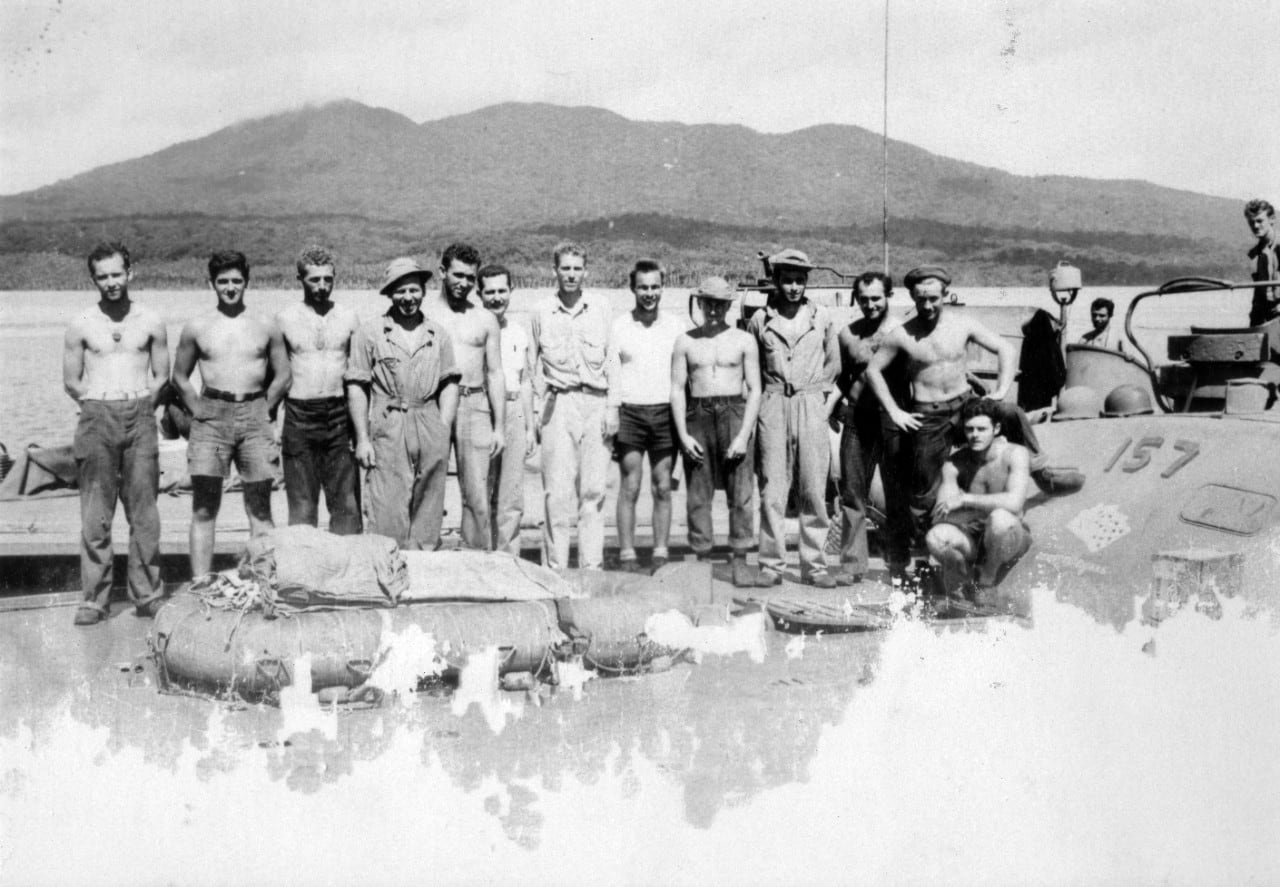

A major goal of the campaign was the capture of the airfield at Munda Point. On June 30, American troops landed on Rendova Island, about eight miles southeast of Munda.

Several days later, two regiments of the 43rd Infantry Division began landing at Zanana, on New Georgia, about eight miles east of Munda. (U.S. forces had already come ashore at the southeast tip of the island and would soon land on its northern shore.)

American commanders quickly deployed artillery on Rendova and the nearby channel islands with which to support their westward drive to capture Munda Point.

June 29: I wonder if they will come today. Last night it drizzled and there was a breeze, making me feel rather uncomfortable. When I awoke at 4 this morning, rain clouds filled the sky but there was still a breeze. The swell of the sea was higher than usual. However, the clouds seem to be breaking.

I have become used to combat, and I have no fear. In yesterday’s raid our air force suffered no losses, while nine enemy planes were confirmed as having been shot down and three others doubtful. Battle gains are positively in favor of our victory, and our belief in our invincibility is at last high.

Some doughnuts were brought to the officers’ room from the Field Defense HQ, which were made by the Nanto Detachment. They were awfully small ones, but I think each one of us had 20 or so. Whether they were actually tasty or not didn’t make much difference because of our craving for sweets.

Each one was a treasure in itself. While eating the doughnuts, I lay down in the sand, and I pulled out the handbook my father had bought for me and which was now all in pieces from a bomb fragment. As I looked at the map of my homeland, which was dear to me, I thought I would like to go to a hot spring with my parents when I get home.

I thought of going there, and here. This map of the homeland, when back home, would be of no use other than for traveling. Right now, it has spiritual meaning rather than a material value: a meaning that is 10 times its value by making me happy and by consoling me.

June 30: At last, the final decisive battle has come.

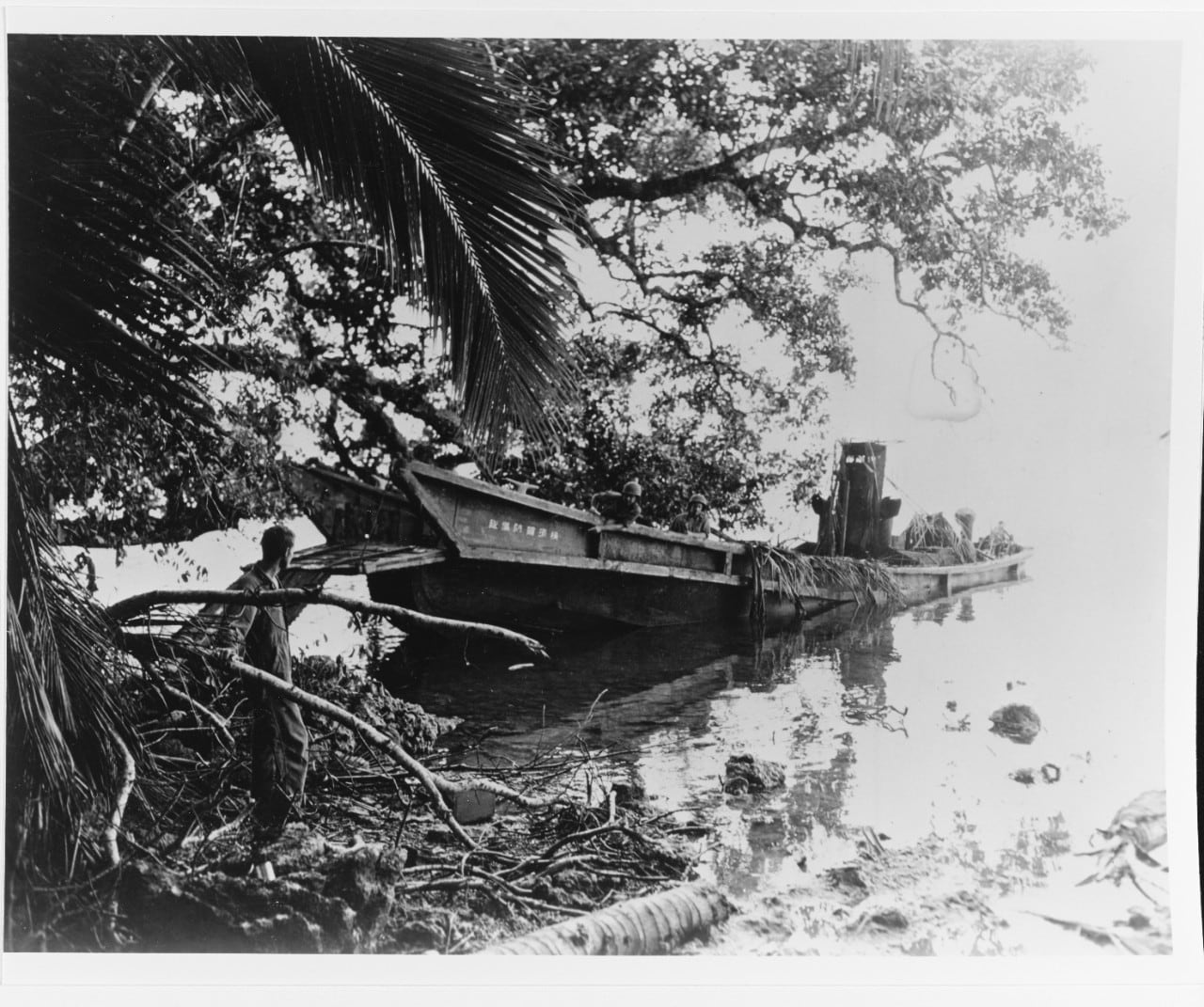

I will relate briefly the progress since last night. Last night, at 7:10 Kolombangara received naval gunfire. At 8, a blue signal flare from Rendova went up. I saw four enemy warships. At 4:10 this morning rain clouds hovered over us. At Rendova four cruisers, two destroyers, two transports, and countless boats appeared.

The enemy fired lightly and the shore batteries replied fiercely. Our guns and air power seemed weak. The enemy used countless numbers of boats and landed on Rendova.

At 8 a.m. our planes finally came. At 8:30 the warships withdrew. About 20 planes kept watch from the sky at all times. There were no friendly planes above. Early in the morning we fired 30 rounds at enemy ships at a distance of 8,500 meters. At daylight there was naval gunfire and a daylight enemy landing.

At 2 p.m., some planes came from the west (Rabaul), I believe, because about 30 medium attack planes are sure a sight.

We are moved to tears and waved our hands, saying, “We’re counting on you; we’re counting on you.”

A report soon came in that [enemy] transports and warships had been sunk. At 2:30 a large formation of 70 planes raided our positions with immense bombs, but no direct hits were scored.

July 1: We received heavy shelling from naval vessels. There was a new attack on Rendova by enemy forces. The report of destroyers shelling Rendova was received, and conjectures of all sorts were exchanged.

Only a few enemy night fighters appeared, and they only circled the coast from time to time. Rain clouds fell about us and at times when we were doing shelter work, we couldn’t see. We transported ammunition, and when we completed the work, it was 2:30 a.m.

All through the night the enemy’s boats moved about. There were no landings, but at dawn (4 a.m.) there were already four enemy warships in nearby waters. At 4:40 enemy fighter planes appeared. After that 20 to 30 enemy fighter planes constantly flew overhead. About every hour the type of planes changed.

At 9:30 a friendly carrier-based fighter [a Mitsubishi A6M-series “Zero”] appeared. Two destroyers were bombed, and one destroyer gave forth bellows of smoke just in front of our positions. At times, the proportion was four Curtisses [P-40s] to one Zero.

Gun reports could be heard from all directions, and there was a roar of friendly light bombers. I filled my stomach with hardtack, and at 7 a.m. we finally finished our fatigue work.

July 2: Because of rain, I got into an air raid shelter and took a nap, getting soaking wet.

At 10 a.m. there’s supposed to be a raid on enemy positions by our fighter planes and heavy bombers. Up until now there has not been any telephone liaison because an order came from the Field Defense HQ for the 2nd Platoon to evacuate after the 1st Platoon had completed preparations for firing.

At 8 a.m. we received naval gunfire from one enemy cruiser. I was scared to death. I stooped over to take a smoke when the shells came. I suppose there will be another naval shelling tonight. If there were only some of our air forces there, the warships would soon be put out of action. When 10 rolled around, friendly planes did not appear as expected.

A report has been received that the enemy was affecting simultaneous landings at Lae, New Guinea, and Arundel. The telegraph was interfered with, and we could not reach the Eighth Area Army [the Japanese army command responsible for the Solomons, headquartered on Rabaul].

We heard that the Eighth Area Army has reinforced nearby units to full strength and has already turned the offensive. Don’t the super-dreadnoughts, Yamato and Musashi, ever move?

Heavy naval shelling continues. At 1:20 p.m. I heard what I thought was the shelling of several ships: It turned out to be friendly bombers. The roar was terrific. To those without binoculars, these were identified as Boeing [B-17s]. I wonder how they felt about these supposed 30 “Boeings” with fighter planes until they were informed they were friendly. What they thought to be an enemy formation were new-model heavy [Mitsubishi G4M2 “Betty”] bombers.

July 3: What kind of operation could our troops be planning? Everything is as the enemy wishes it. Today, again no friendly planes appeared. Not even a boat came. Since the enemy landed, four days have passed, and it must be about time they have completed their positions and general preparations.

If we are going to fight, now is the time — come and get us. I pray that our movements begin an hour sooner or even a day sooner. If it were now, we could beat them. However, we are outnumbered 10 to 1, and our materiel and provisions are limited.

If [we] would only sacrifice a little and pound them on Rendova with the air force and naval shelling, it would be all right. But the way things are going right now, we’re just waiting to be struck by the enemy.

July 4: At 6 last evening, we received a report that the enemy is on the nearest island about 1,000 meters south of our positions, so we fired with 25mm naval guns with instantaneous fuses.

The guns were located 300 meters north of our positions. The shells passed over [our] positions. We cautioned everyone because they were instantaneous fuses.

The enemy did not return the fire.

Last night it rained heavily. Covering my head and crouching, I slept in the corner of the shelter. It was a big storm, and there was terrific thunder from the direction of Rendova, but it was better than being shelled. Everyone got soaking wet, but nobody said a word.

Sleeping on the ground at night and cooling the stomach caused everyone to get diarrhea. We sized up the healthy men, but there were some — like Cpl. Nishimura— who had developed a fever of 42 degrees Celsius [107.6 degrees Farenheit].

Last night, we got wet, too, and I believe it is because of this that our bodies are filthy and our buttocks seem like they were affected by poison oak. It affects our arms and legs.

Noon: The sergeant and I ate in the shelter and we were talking of the landing of 3,000 infantrymen tomorrow night when the descent of a shell interrupted us.

Suddenly a bomber formation appeared from the south. I thought we were going to get it again, but they turned out to be friendly.

After a short time I heard explosions from the direction of Rendova. Out of our 16 medium attack planes, six were shot down by Curtiss planes. [All 16 Japanese bombers attacking Rendova on July 4, 1943, were destroyed, 12 by U.S. Marine antiaircraft fire.]

July 5: Last night’s report was that an enemy force had landed at North Munda, just east of Aidawa [the Japanese name for the Barike River, nearly four miles east of Munda Field].

Kolombangara was shelled by naval fire. Last night, because of poor visibility, both sides ceased firing. They don’t fire howitzers after dark because the flame gives away their position.

July 6: There is a little mountain artillery fire from our side. We could hear the sound of the enemy’s boats, but aside from that, everything was normal.

The report this morning is that a battalion of mountain artillery and two battalions of infantry have landed for guard duty.

At 5 a.m. there was the sound of bombs bursting around North Munda. This more than likely is the landing of friendly troops and of our transports being attacked.

Because of the rain, day after day, and the lack of time for things to dry out, the moldy, sharp odor is terrific. Everything is soaking wet.

Private Ota is an orderly because Iwasato is sick. He used to live with his mother, who is his only living relative. He had supported her by working at a factory. Because he was called up, his 64-year-old mother had to go to work. If they only knew back there that he had come to the front, possibly some help would come from the factory, but he never knew where he would land, and he finally came here.

When they talk of conditions back home, they say he turns to tears. I feel sorry for him.

July 7: The shelling stopped last night. There were no enemy planes either. I came out, and for the first time in some time, I felt like a human being. After it got dark, the quarter moon was to my west at the height of 20 degrees. First it dropped and then it appeared overhead.

If this moon gets round, I bet that the battle will also get more violent.

Yesterday, we were supposed to shell the enemy positions, but it was called off. If we were to do this kind of thing at night, one can never tell what sort of a shelling we would receive because they can see everything from the hills of Rendova.

I prayed that the shells wouldn’t fit well, but they did. I’m almost positive now that they’ll come to order us to fire.

We certainly must not have control of the skies. Our forces must still be mustering warships and transports. They must be using our air force for that purpose.

This morning’s shelling commenced at 8. I went about unconcerned, lying down when some shells burst 30 to 40 meters away from me, which caused me to jump out of my breeches. I don’t exactly appreciate this shelling.

Sgt. Maj. Ishirane, who had gone to Shortland [Island], returned last night. He brought some stationery and some cigarettes. Second Platoon Lt. Obazaki, who was supposed to take up duties here, also arrived.

According to what they say, there is an order that two more probational officers are to be assigned to the 21st Company, but they are being trained at Rabaul at the present.

During the afternoon, a transport laden with AA guns entered Rendova. During the evening, our seaplanes bombed the enemy [naval] base at Rendova.

I could see the firing of the enemy AA guns and their searchlights well. From that action, I judge that there must be six or eight guns.

Three thousand men [Japanese reinforcements] have already landed on Kolombangara. Only 800 men landed at Munda last night because of the shortage of boats. The enemy also landed at two different points, and right now, our forces are attacking the enemy.

July 8: Last evening, I received my first and possibly last mail from home.

It appeared that they haven’t received my letters yet and are somewhat doubtful as to whether I’m still alive or not. They learned that I was on New Georgia. They will really worry if the news of the enemy landing on New Georgia is announced in the newspapers.

Father repeated in his letter that I must fight to the last as an honorable warrior. I will fight to the last, always for the emperor. I will show them that we will fight to the last.

March 6 (letter from father): “There is nothing quite so doubtful as to whether life or death be with one, yet we write at random like searching and traversing a battlefield.”

March 31: “Pray for cherished glory.”

My aged father wrote on April 12: “Even though your soul should remain in the South Sea Islands, follow the will of Heaven.”

Hardly any correspondence of the entire company was more than my own.

The men came up and said, “Sir, it really turned out to be a great mistake to send the sergeant major to Shortland, since it turned out to be all for your good.”

Everyone laughed. It’s all because of my father’s thoughtfulness.

July 9: The artillery barrage started at 2 a.m.

There were great numbers of tracer shells, which made it like day. However, the tracer shells went overhead and did not hit within the positions.

At 5, the firing ceased.

During this shelling, 2nd Lt. Imura (a graduate of Naseda University), who was attached to the searchlight battalion, and one other soldier were killed by a direct hit.

Many officers of my immediate acquaintance were dying right alongside.

When the shelling ceased, three Zero planes came over to reconnoiter and then returned. At 7:30 a.m., about 50 Grummans [TBFs] came over.

Since our positions could be clearly seen from Rendova, we could not fire. I was really fed up when the order came from the Field Defense HQ to fire.

Our CO began to feel sympathy toward the men. He couldn’t figure out any way to fire that wasn’t to our disadvantage.

After he laughingly said, “I would like to die now after seeing the action of our troops," he continued by saying that he would leave all the decisions up to the platoon leaders. He showed a sense of sympathy and never came out with an order to fire.

If our operations would only start, I would fire again and again, even though our positions would be exposed and we in turn would be fired upon. As it is now, we are being fired upon, and we have not returned fire.

Enemy planes are constantly overhead, so I can’t even take a step outside of our shelters. If we were to fire now, they would concentrate their fire on us, and our emplacements would be leveled.

And then all of us would be annihilated together.

We shall fight. Right now, living is more important. In the last stages of this battle, if we can stop the tanks from coming in from the south, then we can die laughing.

July 10: My, the shelling is fierce, but aside from a little scare, the results have been nil. But still, if [a shell] were to hit our shelter, we’re goners.

All of the personnel, wearing steel helmets within the shelters, waited quietly for action. The heat in the shelter was like that of a cellar, and the unpleasant odor drifted about.

It is suicidal to go to the latrine. I put on my helmet, and after I had made complete preparations, I took off for the bomb crater, which was in front of me. While I was defecating, six or seven shells fell, so I took off and came back.

At 3:30 p.m., the shelling ceased. The artillery’s accuracy has become a real thing. We never can tell when we are to die.

Oh, God! I would like to die after seeing the action of our invincible imperial forces. After looking at a dud, I can see that the enemy’s artillery is 150mm [155mm, actually].

July 11: The 13th Infantry Regiment, which was scheduled to land last night, did so at Bairoko Harbor. We are about to take the initiative.

At 7:40 a.m. 45 carrier-based Grummans appeared. Aside from a close hit, all of the rest of the bombs were dropped elsewhere.

During the afternoon for about 2 1⁄2 hours, concentrated fire rained on us. The enemy has fired at least 2,000 rounds today. Some hit within five meters of my shelter.

At this rate, day after tomorrow, I’ll be a goner. The enemy is firing about 20 rounds at a time. Regardless of what shelter I may be in, at the present rate, it will be of no avail.

One of our precious guns was lost in today’s bombing.

July 12: Last evening, I was watching the shelling and some fell within three meters of the positions. It is really a mystery why there have not been any personnel losses up until now.

Right now, I am lying on my side, facing Rendova, with the acting operator, 1st Class Pvt. Tomioka, but today or sometime tomorrow I guess we’ll be hit.

If our last gun were to be destroyed, then our company would become a labor outfit.

Since our mission is that of a tank destroyer unit, we couldn’t very well stay hidden.

We went out to take a peep to the south several times. Fortunately, there were no tanks. When the shelling ceased, we were on the verge of collapse from fatigue and lack of sleep.

At 7 a.m. about 40 Douglas [SBD] bombers effected a general bombing. After about 8:50, we had a concentration of fire on our positions. The 4th Squad’s gun was knocked out. One [shell] burst south and to one side of our shelter, and this made several marks on the aiming apparatus and the barrel.

The ammunition was set afire. Demolition shells must be good only for things above ground level because, queer as it may seem, the personnel are still intact.

This winds up things for this 3rd Platoon leader with the loss of three guns. Losing the guns puts a sense of guilt on me, yet the personnel are intact. There is nothing for us to do but to feel fortunate in the midst of all the bad luck.

From now on, we are a labor company.

July 13: All the personnel assembled where the Field Defense HQ was located, in the midst of shelling, after having come through the dark jungle and over muddy paths.

We dug dugouts in the empty area. After getting wet from the evening dew, we lay down. The distance we traveled really was hard going, so much that it hardly can be expressed.

Sgt. Takagi died last night in the naval shelling. The dead already amounted to 6 to 7 men. Lance Cpl. Ito and four men, who were handling rations, are missing.I must say that there is close cooperation between [the enemy’s] air, land, and naval forces.

Our forces have not carried out a large-scale bombing; they haven’t shelled Rendova with a single battleship, nor have they given the army any heavy artillery pieces.

What do you call this? How could such action be called modern war?

I keenly feel the poor liaison of the Japanese forces and the weakness of our military strength. My! This is really disheartening. We haven’t been fighting, merely dying in the midst of bombs and shelling.

However, the Japanese forces couldn’t let the enemy have his own way; we must look forward with expectations that something will be done.

Probational Officer Oura [the author] has been ordered to be the rifle platoon leader. Probational Officer Takagi has been ordered to be the CO of the 41st Battalion. We are to provide defense and security against the enemy, who is penetrating into the area of North Munda.

The organization is now 27 men and a company of three squads. We are to make it impossible for an advance and attack to be made from any direction.

July 14: Several enemy planes came over early this morning and circled at a low altitude to our rear.

After every reconnoitering, shelling would follow. We are doing our best camouflaging right now. Evidently we haven’t been exposed, because shells are landing 300 meters to our left and right.

The sick, with 2nd Lt. Hattori, are to return from the 41st Battalion sometime today. I am supposed to be in charge of them, and they are to be the 2nd Platoon. I am also to be in command of the rifle platoon.

We rested at battalion headquarters for a little while when the order came for us to wait at the former positions, so we returned. Shells were falling, and there were patients being carried in on stretchers while fighters hovered over us in plain daylight.

It was so bad, I can’t go on talking about it.

At 11 a.m., the order came for Probational Officer Oura and six men to go to the east lookout post, another new position for the Field Defense HQ; 2nd Lt. Imura was killed and a total of four wounded today.

I immediately departed in the rain, and I stumbled time and time again while going through the jungle. On my way, I stopped at Field Defense HQ and received orders. I took command of 12 men, including the medical unit.

As usual, shelling was concentrated on the pom-pom gun positions. The sounds of the explosions and the concussions were terrific.

I lay down in the canvas shelter unconcerned.

July 15: I picked Lance Cpl. Sugiyama, Wakita, Shimura, Muramatsu, and Ota, the six best men. Tomorrow, Cpl. Takahashi and his five men will come and then we will have a strength of 12 men. We are going to start installing a 10cm gun. This east lookout post is the eye of all the forces in Munda.

I set up binoculars and observed the enemy positions.

The U.S. flag could be seen fluttering on PT-boats. A destroyer, which had been camouflaged, was at anchor. You could call [the scene] a war movie or perhaps a “Newsweek” movie [a Japanese equivalent of Movietone or Paramount newsreels].

At any rate, it is interesting to an outsider. The moving boats and bursting shells looked as if you could almost grab them.

This morning’s shelling was a shelling of all shellings. By 7 they had already fired 1,000 rounds into the vicinity of the Kawai Detachment’s positions.

Lance Cpl. Sugiyama was struck. I believe it will take him about a month and a half to recover.

Shells are hitting close by right now, so we can’t go outside.

The offending odor of perspiration in the dugout is unbearable. The place where we stand guard has already become the death ground of two men. No one back home would ever think that we are living in a crater. I am taking the place of 2nd Lt. Imura. It is really smelly.

They said that they hadn’t found the two legs of the men yet.

Four-engine Consolidated bombers [B-24s] fly around at low altitude. I can see plainly through my binoculars two men looking this way from the window to the rear of the insignia.

July 17: I had to lie down inside the narrow dugout because close hits were bursting in great numbers.

Present strength is the CO and 13 men.From 3 p.m., the 41st Battalion fired their AA guns against artillery positions at Roviana for about one hour.

One shell made a direct hit but only after many unsuccessful efforts.

July 18: It rained heavily last night.

The sound of explosions is terrific. Anticipating a landing by the enemy between tonight and dawn, we guarded more closely.

I held the binoculars from 3 to 6:30 a.m., when it was pretty certain that it was safe. I could not sleep on account of the rain and telephone calls that came from Field Defense HQ and the 41st Battalion, and my fatigue mounted.

I inquired about a shell that burst nearby this morning.

I hear the enemy is increasingly concentrating his troops on Guadalcanal for a new offensive. However, we must not complain because our navy and our air force might be striking at Guadalcanal.

If we can only crush Guadalcanal, the enemy at Rendova will be automatically annihilated.

July 19: Last night’s shelling was terrific.

This concentration of fire is just over our dugout. Since it has only one entrance, the air is stuffy, and the sounds of the explosions cause ringing in our ears. It is really more than I can bear. The men were scared, and they all ran into my dugout.

I had to take them out mercilessly and assign them to other dugouts. There were nine men in the dugout, and if it were to receive a direct hit, the entire personnel would be buried alive.

July 20: According to a report, our infantry has completely encircled the enemy at Aidawa and has cut off his ammo supplies. A general offensive is to start within a few days.

At 2 p.m., some 20 bombers came over and dropped a string of huge bombs. Compared to artillery shelling, it is much louder. The concussion is terrific.

The navy gun below the east lookout post has already been fired upon with about 1,000 shells, but it is still firing. It’s a wonder they are still living. It is so hard to believe that they can endure so long. They are showing us vividly the spirit of the Imperial navy.

July 21: All night long, there were reports of small arms and artillery firing.

I heard two wild dogs barking in the distance; I wonder what they could be eating.

Huge shells burst at the base of the east lookout post with great violence. Isn’t there any other place for them to fire at?

In the midst of all the noise, I still slept well. I have come to a point where I have developed a belief that I will not be struck by a shell. The first thing I’m grateful for is my well-being and three meals a day, each consisting of a bowl and a half of rice. All three meals are very appetizing.

My health seems to give me a continuous source of vigor. To be able to eat a heavy meal during the rain of continuous shells is one thing I have looked forward to.

At 8 a.m. we received concentrated shellings of several hundred rounds.

The second tent was thrown helter-skelter, and the first tent received a large hole. The siren shed and the tent where the CO had been staying were destroyed. The lower dugout received a direct hit, but there were no casualties. Huge trees, which had stood for so many years, and others, were knocked down. Consequently, there was hardly any vegetation to be seen in the direction of the east lookout post.

I lay flat along the edge of the dugout for 20 minutes, thinking this was our end, but there were no casualties.

July 22: Last evening, what appeared to be a friendly medium attack plane bombed Aidawa and Rendova twice.

The constant increase of AA guns over Rendova has made it difficult for our planes. The number of shells their AA guns and ours shoot is quite different. It really is a barrage, and they make it so you can’t get in.

The difference between the enemy’s firing and ours is that their searchlight units and guns work separately. Even if our planes do not get in the rays of the searchlights, several thousand shells set up a barrage around the area.

At 8 a.m., carrier-based bombers bombed several places. Most of the bombing was on the troops in the rear, and they strafed them heavily.

To the south of the east lookout post, our navy pom-poms are firing away. If I am to die, there is nothing I can do about it, so I just lay in my dugout, smoking a cigarette and listening to the wild American-made music of “rat-tat-tat” and “boom-boom-boom.”

Just think: I haven’t washed my body or my face nor have I brushed my teeth for a month already. One of my upper front teeth has been broken off.

My body smells like that of a wild dog.

At 2 p.m., I received such fierce shelling that I finally had to dispatch Cpl. Takahashi to ask Capt. Kobayashi as to our future dispositions.

They must have gone crazy in the Aidawa area because they are shelling there for all they are worth. From the way it sounds, it seems like a wild man beating a drum.

Since last night, Superior Pvt. Makita has been with me in my dugout. They fired several hundred rounds while we both lay flat on the edge of the dugout. I used a life preserver for a pillow and a blanket to cover myself. My ears rang as a shell burst one meter to the left and in front of the guard post, and I was covered with coral.

I thought that I was really a goner this time, but I was saved.

Only by staying in the dugout can I say that I’m still alive. The drum in front of the dugout is full of holes. A piece of shrapnel hit my back, and I thought I was finished.

Mysteriously, there were no deaths. We had to do away with a standing guard. We’re just leaving everything open to the enemy.

Oh, friendly forces! Please come to our aid! Show them the might of the Japanese army.

July 23: Battle Situation: Nothing aside from annihilation. No cooperation from the navy.

If I were to compare the complete cooperation of the enemy, it would be like the war of a child with an adult. Our mountain artillery positions were knocked to pieces by enemy tanks. We are encircled, so they say, and about to be overrun. Consequently, all we can do is to guard our present positions.

As things are now, even if our air and naval forces [give] battle, we could not regain the lost ground.

Great numbers of enemy planes are constantly up in the sky. In front of the island, camouflaged destroyers and PT-boats swarm in and out.

What in the world could our forces at Rabaul or the staff of Imperial headquarters be doing? Where have our air forces and battleships gone? Are we to lose? Why don’t they start operations?

We are positively fighting to win, but we have no weapons. We stand with rifles and bayonets to meet the enemy’s aircraft, battleships, and medium artillery. To be told we must win is absolutely beyond reason.

The Japanese army is still depending on the hand-to-hand fighting of the Meiji era, while the enemy is using highly developed scientific weapons.

Thinking it over, however, this poorly armed force of ours has not been overcome, and we are still guarding this island. But this is no time for praise. If [our] forces don’t move, this island will soon be taken.

If we, as well as the enemy, were to fight to the end with all available weapons, then I would be willing to give up, whether we win, lose, be injured or be killed. But in a war like this, where we are like a baby’s neck in the hands of an adult, even if I die, it will be a hateful death.

How regretful! My most regretful thought is my grudge toward the forces in the rear and my increasing hatred toward the Operational Staff.

In the rear, they think that it is all for the benefit of our country. In short, as present conditions are, it is a defeat. However, a Japanese officer will always believe, until the very last, that there will be movements of our air and naval forces.

There are signs that I am contracting malaria again.

Epilogue: This was Oura’s last entry. His fate is unknown, but given the few prisoners taken and the relative handful of Japanese who escaped from New Georgia, it is unlikely that he survived.

Six days after Oura’s final entry, the battered and depleted Japanese forces began withdrawing to Kolombangara and adjacent islands, and Munda airfield fell on Aug. 5, 1943.

For the victorious Americans, some two weeks of mopping-up operations remained before New Georgia was deemed secure.

RELATED

Jack H. McCall Jr. writes from Marietta, Georgia. He thanks Joseph Pratl and the late Frank Bellis for providing the copy of the 37th Division’s translation of Toshihiro Oura’s diary from which this version was made, and Dye Ogata for his verification of its authenticity. This piece originally appeared in the Spring 2005 edition of Military History Quarterly, a sister publication of Navy Times.