NEW BEDFORD, Mass. — Cobblestone streets lead to the New Bedford Whaling Museum where Abigail Field is seated in the library, isolated from the heat and humidity, the blazing sun reduced to a creamy vanilla by the drawn blinds.

At 21, Field, a history major at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, is firmly in the here and now.

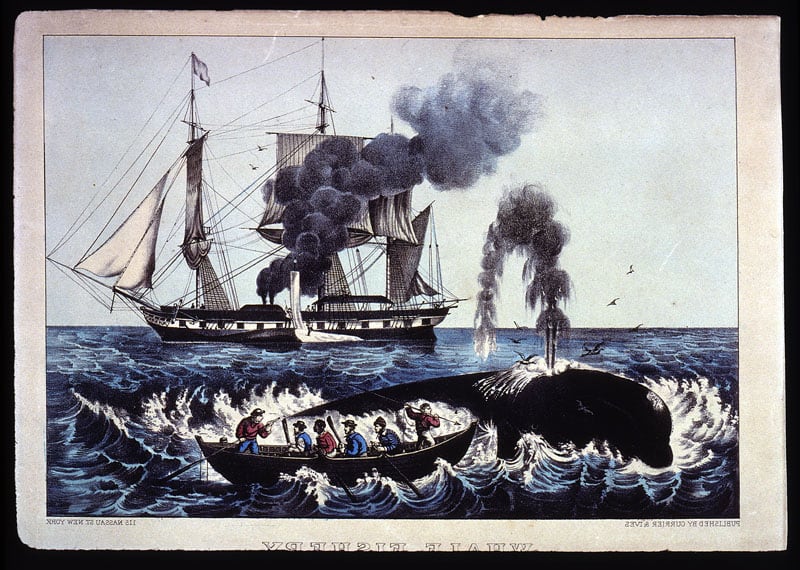

But, for four days a week, she travels with the 18th- and 19th-century whaling vessels that made the ports of New Bedford and Nantucket among the richest in the world. The harbors were filled with vessels headed to exotic locations and the streets lined with the large homes of the dot-com millionaires of their day, whaling captains and ship owners.

As she navigates the ship's log, a forefinger hovering over a particularly intractable scrawl or inscrutable nautical term, Field is in pursuit of certain details like ship location, cloud cover, wind speed and direction, wrung from the ancient mariners' handwriting.

She will add to the database that researchers like UMass Dartmouth history professor Timothy Walker and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Physical Oceanographer Caroline Ummenhofer hope will give context to climate models for some of the most data-poor regions of the world.

"We pitched to (Ummenhofer) that there were large caches of climate knowledge (in the journals)," Walker said.

Log books were a required record of the voyage, turned over to the ship’s owners at trip’s end. The log keeper was required to make a daily entry at noon, but sometimes two to three times a day, that included weather observations and the ship’s position.

Log books were used to determine pay, keep a check on the behavior of officers and crew, and were sometimes submitted as evidence in a trial. The logbook was one of the vital items mariners made sure to take when abandoning a sinking ship.

Walker and Ummenhofer hope to eventually extract data from over 5,500 whaling logbooks and journals, including almost 2,400 in the New Bedford museum.

"We are building up a mosaic of data points," Walker said. "With that we can do fairly sophisticated climate modeling."

It’s not the first time that mundane record keeping has been mined for science.

Ship passenger lists are routinely used in genealogical work, and the “Old Weather” online project employs citizen-scientists in reading digitized reproductions of whaling logs and Navy and Coast Guard ship logs to produce a database of Arctic weather in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Unlike merchant ships and naval vessels, which generally traveled known trade routes, the old whaling vessels went wherever whales could be found, including some of the remotest and least visited parts of the planet, even today.

Ummenhofer is particularly interested in the southern Indian Ocean and its connection to the monsoon season.

"It's an area surrounded by countries without much resources to put into ocean meteorological information. Our good data only goes back to the 1970s, if that long," said Ummenhofer.

“There is a dearth of observation for the ocean interior but big changes are happening there.”

An example is the westerly wind belt that runs between 40 and 50 degrees latitude, known as the Roaring Forties, including the southern Indian Ocean.

Air heated at the equator rises and is deflected south by the earth’s rotation. As it cools, the air drops back to earth along a band that circles the globe between the latitudes of 40 and 50 degrees, producing winds that run unchecked by any large land masses across vast stretches of ocean.

Ummenhofer said that recent research indicates the Roaring Forties is strengthening in the summer and shifting south into the region known as the Furious Fifties.

"It's one very strong (climate change) signal, but hard to put into context because there's very little (long term) observations," said Ummenhofer.

She is also looking for longer term data on the monsoon season when a change in the prevailing wind over the Indian Ocean in summer brings the heavy rainfall the agricultural and hydroelectric power industries are dependent upon. A weak monsoon season can mean food shortages and expensive power.

Winter monsoon winds originate over China and Mongolia and bring dry conditions, sometimes drought.

On Saturday of March 23, 1867, a year into a nearly five-year whaling voyage, an unnamed log keeper on the Adeline Gibbs, a New Bedford bark that was hunting whales in the southern Indian Ocean, midway between Madagascar and Antarctica, noted that a persistent gale had finally abated.

"It's been raining for the past month for him, so I guess he had a good morning," Field said, her finger lighting on the log keeper's neat 152-year-old cursive, likely copied into the book when the vessel was in port from the less-legible notes taken while the ship heaved on storm-tossed seas.

"Usually the log keepers give the lat/long (ships position by latitude and longitude), but he kind of stops giving the lat/long at a certain point and just says they are around the Crozet Islands," Field said.

The Crozets are hardly a tropical paradise and the view from the deck was not that of a welcoming refuge from the sea.

Enormous cliffs — the islands are the peaks of a sunken volcanic mountain chain — rise vertically from the ocean, with only moss and lichens for vegetation.

The islands are home to hundreds of thousands of penguins, seabirds and seals, and the local killer whales that have learned the unique trick of beaching, then un-beaching themselves while chasing their prey onto the rocky shoreline.

"This guy isn't very talkative," Field observed.

But the handwriting and diction are easily read and understood. Not so with other logs and journals, especially those on earlier 18th century voyages, which are plagued by “horrible spellings, no syntax and punctuation,” Walker said.

RELATED

For accuracy, the conditions noted in one ship’s log are cross-referenced with journals and/or logs of other vessels operating nearby.

The team from UMass and WHOI are presently focused on the Indian Ocean, working their way through 650 logbooks and journals looking to gather eight or nine data points: wind direction and speed, vessel direction, lat/long, sea state, landmarks, relative air temperature through observation (if the deck tar is melting, for instance, it's really hot), precipitation and currents, said Walker.

It’s labor-intensive work, sometimes with a magnifying glass, that involves skilled interpretation of archaic handwriting, old nautical terms, and decayed logbooks battered by the sea and the intervening centuries.

Although as an historian Walker can appreciate chattiness, with hundreds of log books to get through, he prefers the laconic scribes who stuck to the facts making 30 entries on a single page.

Field enjoys the occasional distraction like the log keeper who made notes in the margins about the prostitutes the ship’s crew encountered, or the colorful watercolors that adorn the pages of some log books.

Many of the crew on whalers and other 18th- and 19th-century sailing vessels hailed from the region's interior, like the inland farms of New England, and Field was particularly taken by a scribe who announced the birth of piglets in his log entry one day with an accompanying drawing.

“Here’s a guy who had sailed all over the world and seen some of the most beautiful places on the planet and he hadn’t said ‘Oh, this place was beautiful and that place is beautiful,’” Field said. “He never uses the word except on the piglets and ‘Oh, they were beautiful.’”