Between Aug. 7, 1942, and Feb. 9, 1943, U.S. forces sought to capture – and then defend – the Pacific island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese military.

What started as an amphibious landing quickly turned into a series of massive air and naval battles.

The campaign marked a major turning point in the Pacific theater of World War II. It also revealed important lessons about the nature of warfare itself – ones that are particularly relevant when planning for conflict in the 21st century.

Specifically, the Guadalcanal campaign shows how the old saying “the best defense is a good offense” can be turned upside-down – with a strong defense becoming an effective offensive weapon. The Japanese sought to find weaknesses, but kept running up against American power on land, on the sea and in the air.

As scholars and military professionals, we see Guadalcanal as teaching enduring lessons about the importance of integrating planning, training and technology to generate options that confound an adversary.

We are not alone. The Chinese Navy’s official magazine recently published an article analyzing the Guadalcanal campaign for lessons useful in future wars.

Defense as offensive strategy

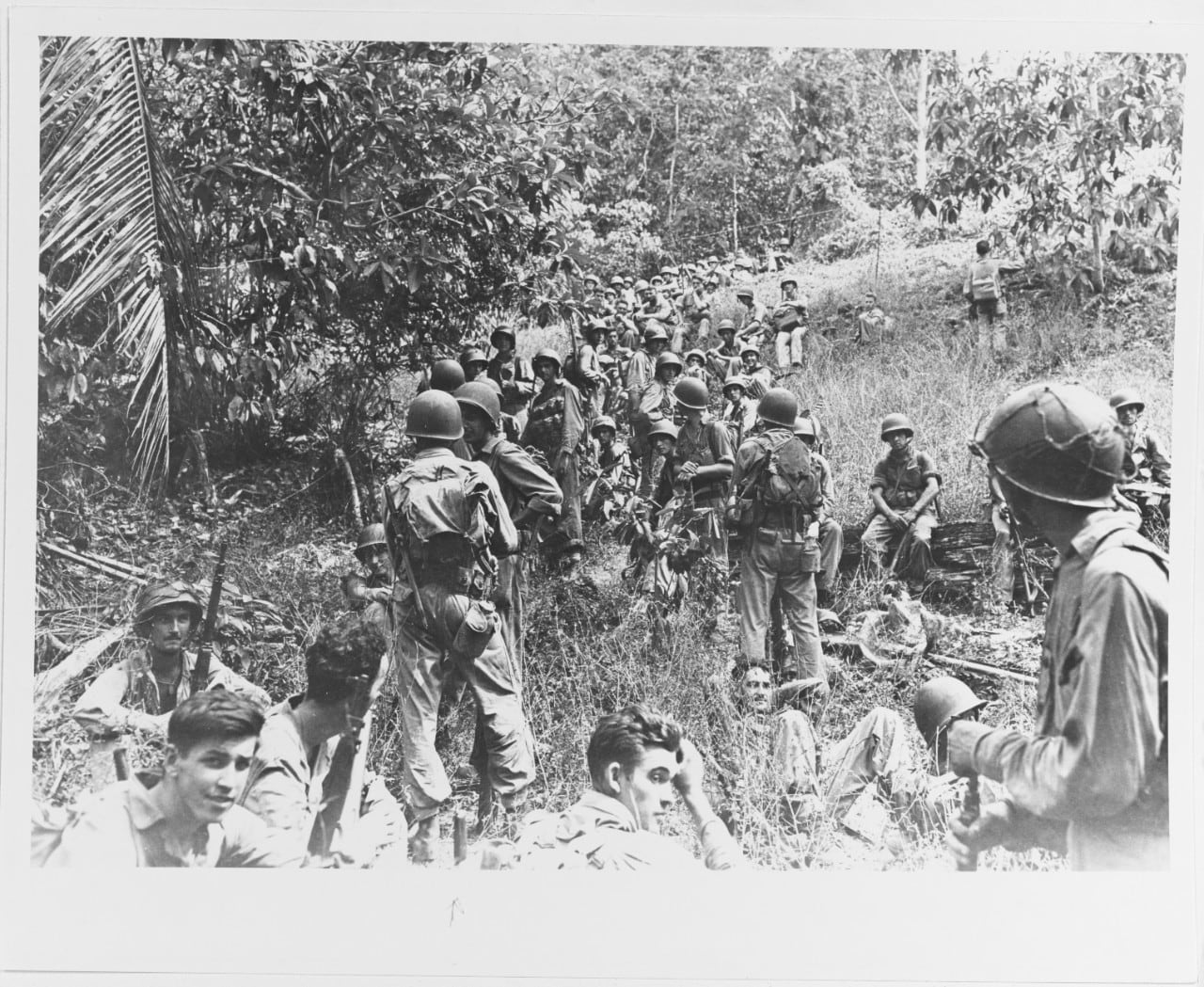

In early August 1942, the United States landed Marines and other troops on Guadalcanal, taking much of the island and capturing its airfields. Initially, it was an offense-as-defense strategy, part of a larger effort to capture the Solomon Islands, so Japan couldn’t use them as a base for attacking Allied naval forces in the Pacific.

Japanese resistance took a heavy toll, especially on the U.S. Navy, which lost 29 ships and thousands of sailors. But the Japanese efforts did more lasting damage to its own military, expending pilots, aircraft and ships Japan simply could not replace fast enough to sustain the war. The U.S., by contrast, had a vast population and enormous industrial potential, and was able to replace its losses and even reinforce its positions.

Realizing the Japanese had committed to retaking Guadalcanal no matter the cost, the U.S. strategy shifted to defense-as-offense, or what is called a “cost imposition” campaign. It’s most often seen as a business strategy, but can be applied to military efforts too.

In general, cost imposition involves making it very expensive – in personnel, equipment and time – for an adversary to achieve a particular goal. This presents the enemy with a serious dilemma: Giving up means certain defeat, of course, but continuing to compete decreases the likelihood of winning.

At Guadalcanal, the Japanese fell prey to the “sunk costs fallacy,” deciding that because they had spent so much already, they should just keep going. They found their battleships matched not only against the U.S. warships and planes, but also bulldozers, as U.S. Marines repaired key airfields in between barrages of shelling from Japanese ships offshore.

While the Japanese Navy expended round after round of ammunition, American planes were still able to take off and land, conducting repeated raids that sank or damaged the Japanese warships.

RELATED

Drone swarms, advance bases and cyber defense

Today, the United States faces a complex mix of threats. Global powers like Russia and China use politics and economics as well as military strength to achieve their goals. Terrorists and hackers spread fear, uncertainty and social discord within the U.S. All of that puts the U.S. at risk of ending up on the wrong side of cost-imposition efforts from adversaries big and small.

Expensive aircraft carriers and advanced aircraft can be threatened by much cheaper missiles wielded by extremists. Hackers can threaten military bases and weapons – as well as civilian infrastructure like power plants.

In our view, the U.S. military therefore needs a new approach to defense strategy.

First, the country needs entirely new classes of cheap, disposable drones that engage targets on land, at sea and in the air. For example, low-cost drone swarms could help U.S. Marine forces threaten enemy naval and ground assets, while counter-drone systems protect U.S. forces. Like Guadalcanal’s bulldozers, they would offer a cheap way to keep the enemy under threat.

Second, Guadalcanal also highlights the importance of being able to rapidly build and defend advance bases. Into the future, the U.S. Marine Corps will need to be able to construct and repair airfields. They’ll also need to be able to use those locations as airplane, drone and missile bases to attack enemy forces.

In addition, those bases can block the enemy from using key terrain, and give the U.S. multiple options if a strike is needed. Those factors again raise the cost of conflict and competition for a potential adversary.

Education matters, too

A further lesson from the Guadalcanal campaign is that it’s vital to integrate new technology into training, so Marines and sailors know how to use new capabilities. In early August 1942, the U.S. Navy suffered one of its worst-ever defeats in the Battle of Savo Island. American and allied forces lost four cruisers, while the Japanese Navy suffered little damage.

The U.S. had a significant technological advantage, but didn’t use it: radar. Few ship captains and crews understood how radar worked, much less how to use it in battle. One captain, Howard Bode of the Northampton-class cruiser Chicago, ordered his ship’s radar turned off, for fear it would reveal his position.

Later on, in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands in October 1942, the U.S. ships again did not use their radars. The Japanese used their searchlights to spot American aircraft at night, controlling the battle in the darkness and sinking one U.S. aircraft carrier and severely damaging another.

The lesson remains important in the 21st century: Failing to experiment with new capabilities, whether radar in the 1940s or cyber operations and drone swarms today, diminishes battle readiness. That’s why the Marine Corps University created war-gaming fight clubs and training programs that let students imagine future conflicts and experiment with how to respond.

Battles can be won before the first shot is fired, if future leaders prepare in classrooms and training for what they might face and how they might find advantages when conflict comes – whether online, in space or elsewhere.

Dr. Benjamin M. Jensen’s teaching and research explore the changing character of political violence and strategy. He holds a dual appointment as an Associate Professor at the Marine Corps University, Command and Staff College and as a Scholar-in-Residence at American University, School of International Service. At Marine Corps University, he runs the Advanced Studies Program. The program integrates student research with long-range studies on future warfighting concepts and competitive strategies in the U.S. defense and intelligence communities.

Brig. Gen. William J. Bowers is past president of Marine Corps University. His decorations include the Legion of Merit (with gold star), the Bronze Star, the Defense Meritorious Service Medal (with oak leaf cluster), the Meritorious Service Medal, the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal (with two gold stars), the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal, and the Humanitarian Service Medal. He was named “Combat Engineer Officer of the Year” in 1998 and has received several writing awards.