It was August 1929, but the tiny Russian hamlet of Verkne Imbatskoye moved to the rhythms of another century.

A cluster of thatch-roofed log cabins, the town clung to the banks of the great Yenisei River in Siberia. Cocooned from the outside world by thousands of square miles of dense forest and marsh, Imbatskoye scratched a bare living from its surroundings. Horse-drawn carts rumbled along dirt paths, and smock-clad peasants greeted each other as they passed by. It was an ordinary day, timeless in its routine, but the 20th century was about to intrude in a big way.

An unfamiliar noise filled the air, a kind of rumbling moan that drowned out the normal barnyard chatter of domestic animals. Then, all at once, the villagers saw it — a great silver monster looming over the horizon, heading straight for the defenseless scattering of cabins.

The aerial beast was as big as a mountain, its shadow so huge the village could be eclipsed into a momentary “night.”

For all is mammoth bulk, the creature floated easily in the sky and seemed to be moving under its own power. Was this a sign of Armageddon? A judgment on Stalin and the godless Communists ruling in Moscow? Or heaven’s punishment on the villagers for their own sins?

Panic gripped Imbatskoye like the icy hand of doom. Peasants rushed into their houses and barred the doors; others, rooted in sheer terror, gazed transfixed in horrified awe. Even the animals were panic-stricken; a horse galloped wildly though the dirt streets, harnessed to a cart that smashed into two cabins and demolished them.

The great silver object was neither an extraterrestrial visitation nor a supernatural sign, but the Luftschiff (airship) Graf Zeppelin, a passenger dirigible on an around-the-world journey.

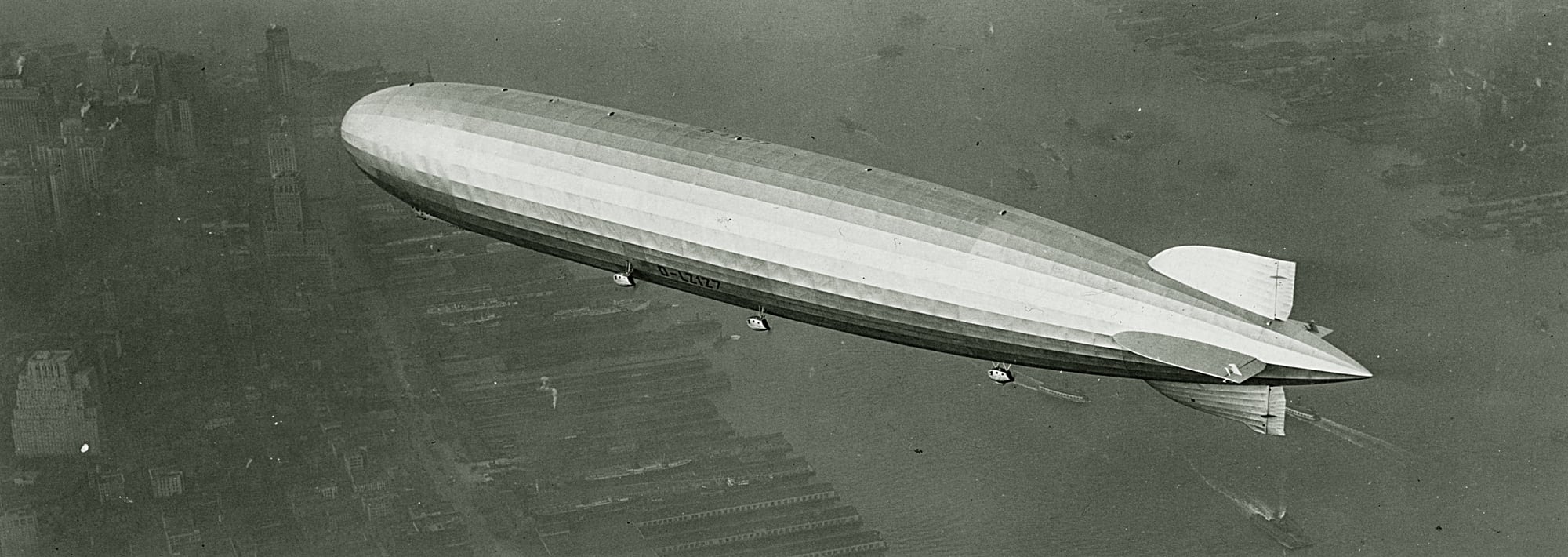

The 775-foot-long, cigar-shaped craft was looking for a landmark as a navigational “fix,” and tiny Imbatskoye provided that information.

Graf Zeppelin glided on eastward, leaving behind a hamlet that would never forget its rude visitation.

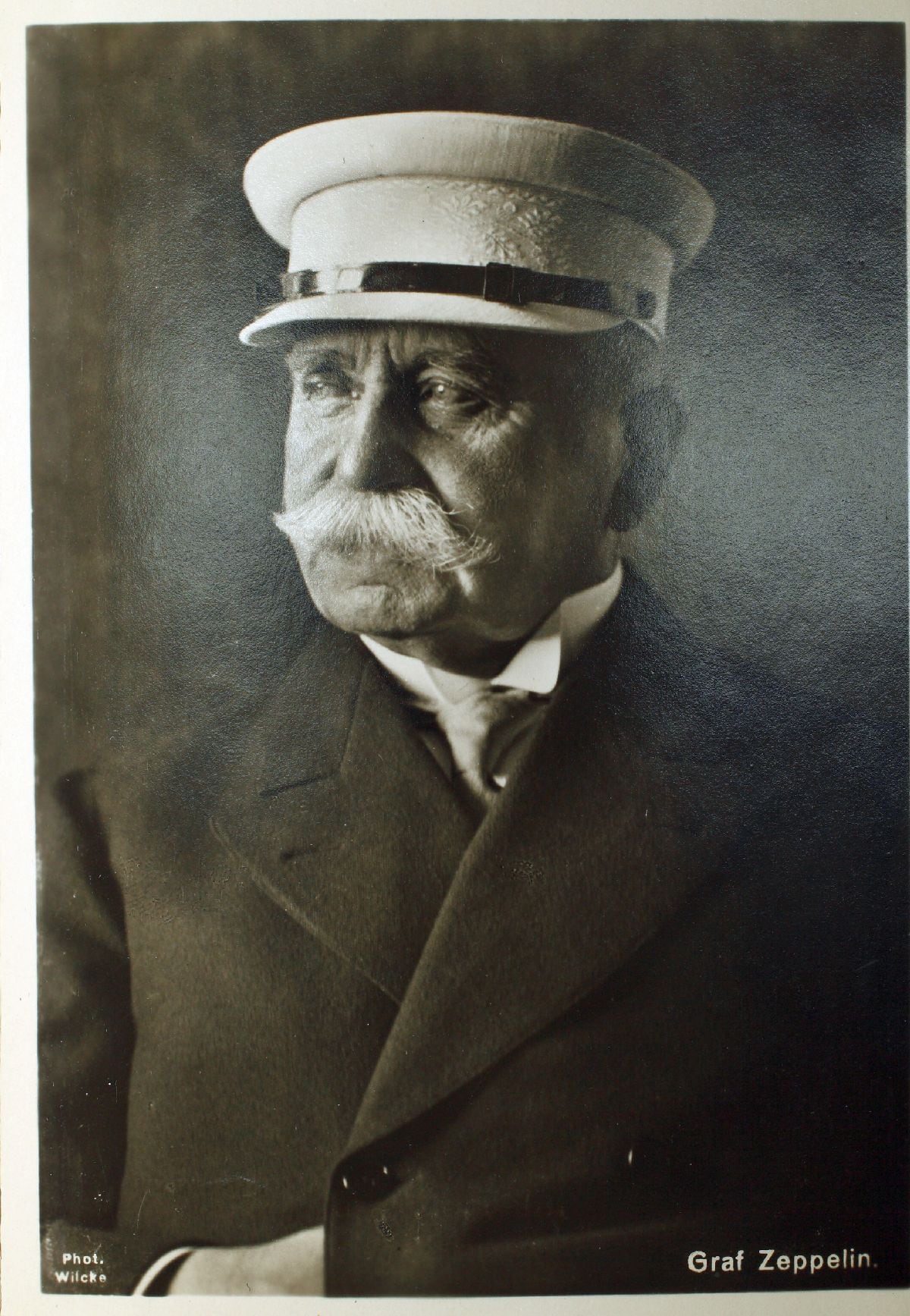

The airship Graf Zeppelin was named in honor of Graf (Count) Ferdinand von Zeppelin, father of commercial dirigible aviation.

In a sense, Graf Zeppelin‘s world-circling tour began in 1900, when the count first experimented with airships. Zeppelin’s great idea was to produce rigid airships, not merely gas-filled balloons.

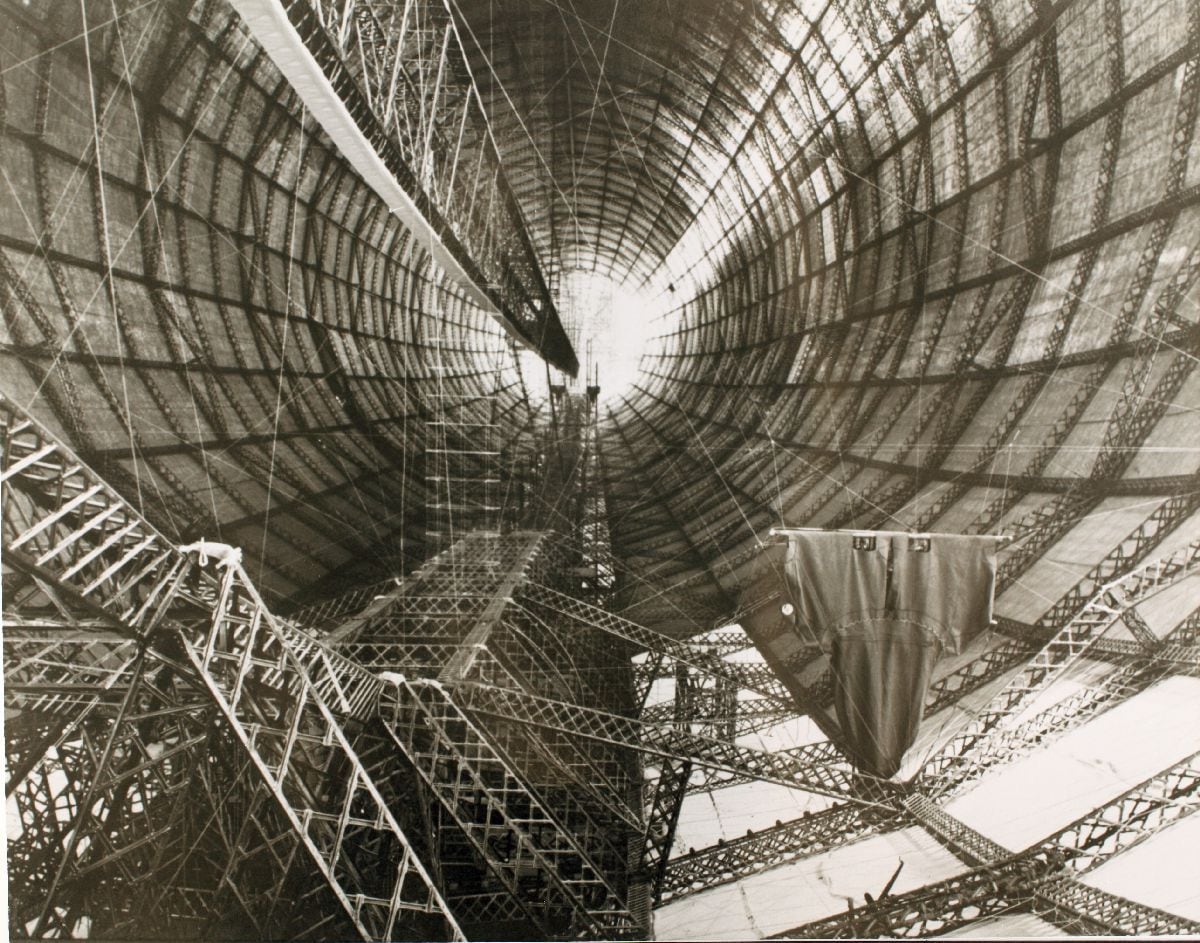

According to this plan, the airship envelope was held firmly in shape not by internal gas pressure, but by a rigid metal skeleton. The lifting gas — hydrogen, in this case — would be housed in a series of self-contained cells within the metal skeleton’s “ribcage.”

By 1914, the count’s airships — nicknamed Zeppelins after the grand old man himself — were a moderate success, carrying fare-paying passengers throughout Germany. When World War I broke out, the Zeppelins were converted to military use, chiefly bombing England.

The Zeppelin raids did some damage, but their main effect was psychological. After the first shocks, the British learned that these sausage-shaped monsters were slow and vulnerable. Incendiary bullets were developed that turned the hydrogen-filled German raiders into flaming coffins.

When Germany surrendered in 1918, its airship industry was in ruins.

Count Zeppelin had died in 1917 at the age of 79, but he had a worthy successor in Dr. Hugo Eckener.

Eckener had been with the Zeppelin company for years, working his way up from publicist and aide to operational chief in 1922. The torch had been passed to able hands, but Eckener had to keep the light alive in the dampening rain of Allied restrictions, lack of funds and public indifference.

The allies had imposed harsh terms on a vanquished Germany, and the airship industry suffered with the rest of the country. All remaining Zeppelins were confiscated by the Allies, and severe restrictions were imposed on building others. Military Zeppelins were completely forbidden, and commercial ones were to have a maximum gas capacity of 1 million cubic feet — far too small for the long-distance dirigibles Eckener had in mind.

To help the Zeppelin company survive the lean times, Eckener converted its metal-making facilities to produce household kitchen utensils. Gradually, the political climate changed for the better, and the harsh restrictions were lifted in 1926. Eckener gratefully switched from making pots and pans to building airships.

But financial troubles still loomed. The German economy was still recuperating from the terrible inflation of 1923, when it took more than 4 trillion marks to equal one U.S. dollar. Times were better, but in 1926 neither the German Weimar Republic nor the Zeppelin company had the funds for a major airship project.

Ever resourceful, Eckener turned to the German public and launched a direct subscription appeal. After touring throughout the fatherland, the Zeppelin chief raised 2.5 million marks — far short of the goal, but enough to start. Eventually the German government pitched in and made up the balance.

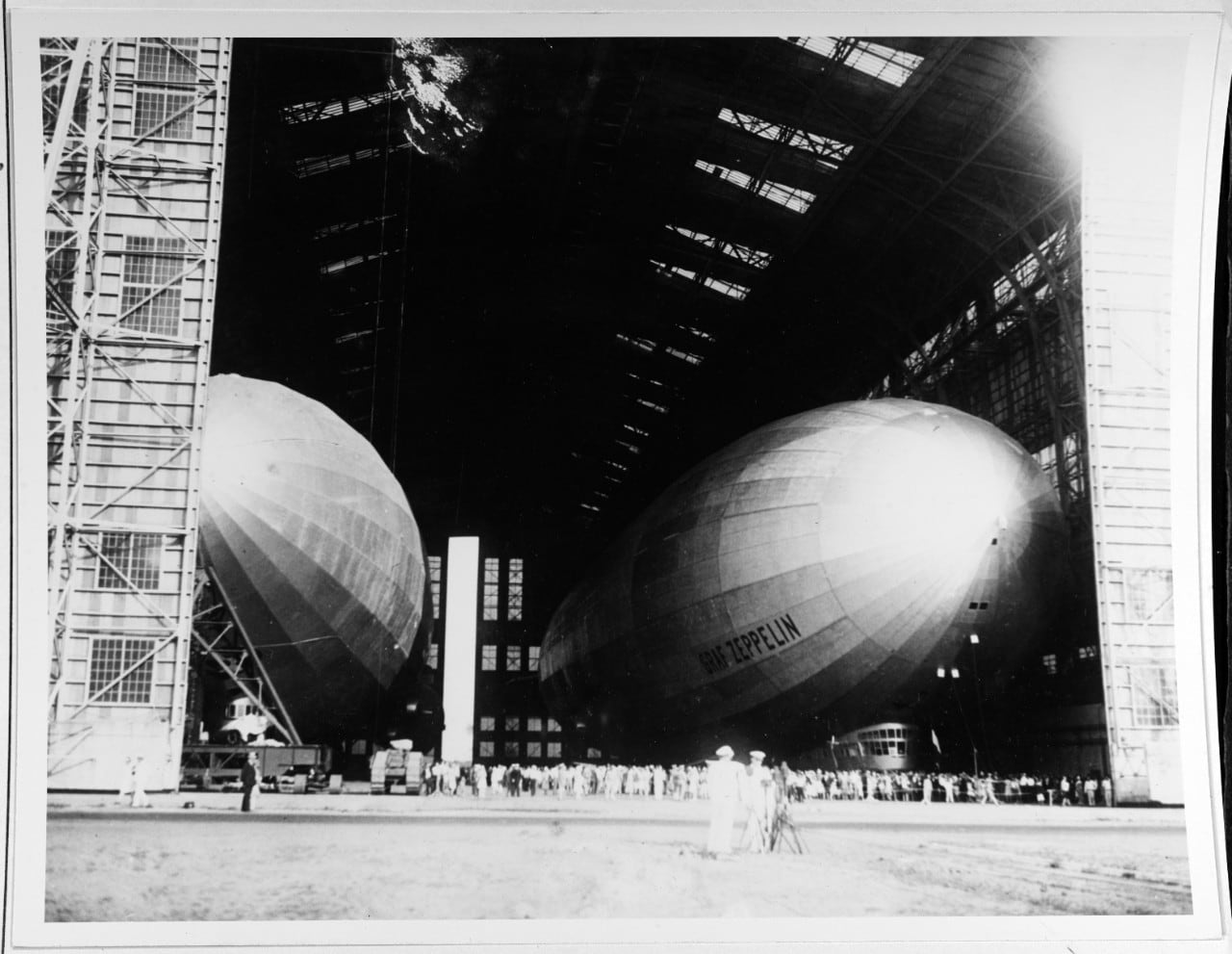

With the necessary funds in hand, work began immediately on the new airship. Months later, on July 8, 1928, Countess Helga von Brandenstein-Zeppelin smashed a bottle of champagne across the bow of the newly completed dirigible and christened it Graf Zeppelin in honor of her late father. Graf Zeppelin‘s official designation was LZ.127, but soon everyone affectionately called it simply Graf.

Everything about Graf was monumental; in fact, it was the largest dirigible yet seen. Designed by longtime Zeppelin architect Ludwig Durr, its gigantic bulk measured 775 feet from nose to tail, with a girth of 3.7 million cubic feet. That translated into an airship that was 10 stories high and more than two city blocks long.

Critics maintained that Graf was too slender, too “skinny” for peak aero-dynamic efficiency, saying a stouter shape would have permitted a smoother air flow.

No matter; a worshipping public loved the ship as it was. Looking something like a giant silver torpedo, Graf‘s outer skin was made of heavy-duty cotton, stretched so taut that the revealed outlines of its metal skeleton produced a fluted design effect on its body.

The airship’s skeleton was composed of a series of main and secondary rings, braced to the ship’s keel and linked together by longitudinal girders. The main rings were made up of diamond-shaped trusses. The rings and girders were made of a light aluminum and copper alloy called duralumin.

Duralumin was as strong as steel yet only one-third as heavy; even so, Graf contained 33 tons of this metal.

There were 17 gas cells within the mighty airship, held rigidly in place by a spider’s web tracery of rings, girders and bracing. The gas cells were made of cotton fabric, each with an airtight lining of membranes from the intestines of oxen. It took some 50,000 membranes to line just one gas cell, and the cost was enormous.

The upper cells held hydrogen for lift, the lower cells a gaseous fuel similar to propane, called blau gas.

The lighter-than-air hydrogen provided buoyancy, and forward propulsion was supplied by five Maybach VL-II engines, each mounted externally in its own gondola. Their twin-bladed — later four-bladed — propellers were mounted pusher-style, and the engine nacelles were big enough for a man to crawl inside and perform in-flight maintenance.

A tear-shaped gondola was mounted forward, a small “mole” on the ship’s nose that did little to break its smooth, clean lines. Measuring 98 l/2 feet long by 20 feet wide, this passenger gondola housed the control car, galley, chart room, radio room, dining room and a double row of 10 sleeping cabins. Washrooms and toilets were behind the sleeping cabins.

Unseen by passengers, Graf‘s keel inside the envelope was honeycombed with other rooms: crew “bunkhouse,” generator room, cargo rooms and others.

Graf Zeppelin was not only an airship but also a work of art. Aesthetics and aerodynamics seemed to meet in its graceful form.

Its cotton skin was protected by no fewer than six layers of paint and dope. The paint was silver, the better to reflect the sun’s rays and thus reduce the heat inflation of the hydrogen. As an added touch, the painted surface was sandpapered smooth, leaving a “sculptured” sheen that offered little wind resistance.

After a few shakedown flights, Graf departed on its maiden voyage to America in October 1928.

Ironically, the giant airship’s first major flight was almost her last. At first all was quite routine, except that certain items like bottled water were running out. Just south of the Azores, in mid-Atlantic, the passengers were just sitting down to a sumptuous breakfast when an ominous wall of clouds appeared on the horizon.

These swirling, blue-black masses slammed into Graf Zeppelin, causing its nose to dip sharply down before rising upward at a 15-degree angle.

Nature had literally turned the tables on the passengers, as furniture was upset and people slid to the floor. Terrified passengers fell on each other in an avalanche of crashing plates, saucers and food. The battered voyagers were festooned with sausages and splattered with gobs of butter and marmalade, but it was Eckener who had egg on his face — he had to right the ship at once.

When Graf was literally on an even keel again and the immediate crisis had passed, the passengers could congratulate themselves on their survival. But such backslapping was premature — Graf had sustained serious structural damage.

The violent turbulence had shredded the port stabilizing fin; worse, ripped pieces of fabric floated outward like streamers, threatening to jam the rudders and elevators.

After ordering the ship to slow to half-speed, Eckener called for volunteers to repair the damage. It was a dangerous assignment; the volunteers would have to crawl out onto the damaged stabilizer, clinging to its exposed girders while being buffeted by howling winds.

Nevertheless, four crew members — including Eckener’s own son Knut — went out and repaired the damage. The fabric “streamers” were cut away and the frayed edges of the break lashed down.

Graf Zeppelin completed its inaugural journey to America and conducted a triumphal tour of Washington, Baltimore and New York City.

Its fame grew until the silver colossus became a legend in its own time and half the world seemed gripped by “Zeppelin fever.”

To keep the publicity mills turning, Eckener undertook a series of demonstration flights around Europe and the Mediterranean. Word spread that a voyage on Graf was a marvelous experience, with breathtaking scenery and first-class service.

But to Eckener, Graf Zeppelin was literally a trial balloon.

Although he was not in favor of building more giant airships until public response showed there was a need for them, the good doctor was wise enough — and showman enough — to create that demand by keeping his airship in the public eye via spectacular stunts.

The public’s growing affection for Graf was a positive sign but the jury was still out on the future of airship travel.

Eckener decided to pull out all the stops; he would take Graf Zeppelin on an around-the-world cruise, something no commercial aircraft had ever attempted.

Although he was rich in dreams, Eckener was poor in cash and needed financial backing for his proposed globe-girdling jaunt.

American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst stepped forward and offered to bankroll the project to the tune of $100,000.

No serious strings were attached, but Hearst did insist on exclusive story rights, and that the journey begin and end on U.S. soil.

Eckener accepted, so the start and finish point of the tour would be the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey.

It was then a matter of selecting the route. To begin with, Graf Zeppelin was going to circle the earth from west to east, with the first leg from the United States back to the Zeppelin base at Friedrichshafen.

Where next? The only suitable dirigible hangar in the entire Far East was located at the Japanese naval base at Kasumiga-ura, so Japan was an obvious port of call. Some consideration was given to flying east via the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and the China Sea, but that route was rejected because it was too long.

Poring over maps and charts, Eckener decided on a far northerly course, one that would take Graf over Russian Siberia to Yakutsk, thence to the Sea of Okhotsk and Japan.

After Japan, the airship would strike east across the Pacific to California, then on to its starting point at Lakehurst.

When preparations were complete, Graf Zeppelin departed Friedrichshafen on Aug. 1, 1929, bound for its official, Lakehurst world cruise starting point.

Additional revenue was provided by the sale of thousands of commemorative postage stamps.

Indeed, Graf carried mail on this Atlantic run, and collectors were later thrilled to receive letters with its distinctive cancellation mark, a blue ink stamp with a logo showing the Zeppelin floating over the New York skyline, and bearing the legend “Luftschiff Graf Zeppelin — Amerikafahrt 1929.”

Graf Zeppelin departed from Lakehurst on its epoch-making global journey on Aug. 7, 1929, while a brass band serenaded the airship with the all-too-appropriate tune “There’s a Long, Long Trail.”

The Lakehurst-Friedrichshafen hop was uneventful and took some five hours. Once back in Germany, there was a five-day layover while the ship’s engines were thoroughly checked. They had to be; the most perilous leg of the journey lay just ahead, a 6,800-mile nonstop flight to Tokyo.

There were 20 passengers aboard, an international mix that included Japanese, Americans, British, a Spaniard and, of course, Germans.

One of the Americans was Lt. Cmdr. Charles Emery Rosendahl, the U.S. Navy’s top airship man. Britain and its Commonwealth were represented by arctic explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins and Lady Drummond Hay. Besides being a Hearst journalist, Lady Hay was the only woman aboard.

There were also representatives from destination countries, including a Comrade Karklin of the Soviet Union. Karklin was on board as the official representative of the Soviet government, there to watchdog the operation when Graf flew over Russian territory.

The rest of the passenger roster was made up of reporters and well-heeled private passengers, some of whom paid as much as $9,000 for a ticket on this historic flight. Competition was fierce, and apparently Graf was slightly overbooked. Some paying passengers were left behind because of weight considerations.

When Graf left Friedrichshafen in the early hours of Aug. 15, the passengers knew that the next time they set foot on solid ground it would be Japanese soil. The silvery colossus nosed northeastward, past Ulm, Nuremberg and Leipzig while reporters filed stories and passengers amused themselves.

An American put on a phonograph record in the dining room, causing an otherwise staid Japanese reporter to dance a wild Charleston.

A few hours later, at about 10:30 a.m., Graf reached Berlin. The German capital was magnificent from an altitude of 750 feet, with the Spree River winding ribbon-like through the city of stately buildings and broad avenues. The streets were already thick with people, all gazing heavenward, and more poured out of the buildings as Graf floated past.

As the mighty airship soared over the Brandenburg Gate and swept up the Unter den Linden past the Alexanderplatz, the drone of its engines could not muffle the cheers of the assembled thousands below.

Leaving Berlin in its wake, Graf Zeppelin continued eastward, first to Danzig (now Gdansk), and on to Lithuania.

As soon as the Russian border was crossed, Comrade Karklin appeared in the control car to “advise” Eckener on where the airship could and could not go. As it was, Eckener had gone through protracted negotiations to obtain Russian permission for this flight; now he had to put up with Karklin’s carping.

Hoping to score a propaganda coup, Karklin insisted that Graf Zeppelin visit Moscow, where he claimed “thousands” were awaiting the arrival of the mammoth airship. (Western reporters in Moscow reported no unusual activity; no crowds, no Zeppelin fever of any kind.)

Eckener considered Karklin’s “request” but rejected it on meteorological grounds. A low-pressure area over the Caspian Sea was creating contrary east winds over the Russian capital, and Eckener wanted to take advantage of a west wind farther to the north.

Karklin was not pleased by the doctor’s decision, but there was little the Bolshevik could do except jump ship — and it was a long way down. Lacking a parachute, he stayed aboard, a sour Communist presence amid capitalist luxury.

Graf journeyed on, spinning propellers boring into the air, until Vologda came into view. As the dirigible grew nearer, this ancient Muscovite town seemed like an Arabian Nights dream, its golden, onion-shaped church domes sparkling like a chest of jewels.

The airship crossed the Ural Mountains just north of Perm and entered Asia. For the next few days, Graf would travel through Siberia, fabled land of exiles, a region so vast that parts of it were still uncharted. As human habitation grew scarce, navigation would be by dead reckoning, just as in an ocean voyage.

The land below was the Siberian taiga, a vast forested wilderness larger than the continental United States. There was an eternity of trees, a green mantle that stretched hundreds of miles, its immensity broken only by marshes and a few meandering rivers. Vast stands of fir and spruce poked up, giving the emerald carpet a spikey texture, and below their sheltering limbs lurked bear and elk and other wild creatures.

The contrast could not have been more striking: Passengers would gather at the lounge/dining room to feast on fine food and choice wines in an atmosphere of refined elegance. The menu featured such things as pate de foie gras, lamb chops and caviar, all served on fine Bavarian china bearing the Zeppelin logo. In these regions, the passenger gondola was literally an island in the sky, a tiny bit of civilization hung suspended between heaven and earth.

If Graf suffered an accident and went down here, impaled on the fir trees’ spikes, the voyagers had little hope of rescue. Their lives literally depended on Eckener and his airship.

Eventually the Siberian terrain grew monotonous, although there was a momentary spectacle when a huge forest fire was spotted. Black coils of smoke marked the fire’s progress, and many acres were consumed, but in truth such conflagrations were fairly commonplace in Siberia.

This far north, the sun barely disappeared at night, but left a telltale pink smear on the horizon that seemed to anticipate dawn. It was cold, too, and passenger cabins were unheated. When the voyagers assembled for breakfast some mornings, they looked more like skiers than airship travelers, bundled up in camel-hair coats, sweaters and other wintery garments.

After reaching the Yenisei River basin and making that navigational fix on the startled village of Imbatskoye, Graf roared onward toward the Tunguska region. Eckener was hoping to find a crater left by the celebrated Tunguska Event 21 years before.

On June 20, 1908, an enormous explosion had rocked this part of Siberia, so powerful that every tree within 20 miles was knocked flat. Shock waves from the blast knocked horses off their feet 100 miles away, and some house roofs were destroyed. It was similar to a high-altitude hydrogen bomb detonation, and has long been a mystery. In the 1920s, most scientists felt it had been a meteor, and so should have left a telltale crater.

Graf Zeppelin searched in vain for the crater and eventually had to move on. Today scientists speculate that the cause was a piece of comet, a “dirty snowball” of water and gases that exploded and vaporized on entering the earth’s atmosphere, and so left no crater. In any case, Graf finally reached Yakutsk, a fur-trading town on the banks of the five-mile-wide Lena River. The next hurdle lay just ahead, the Stanovoy mountain range.

The Stanovoy mountain range was not well known; even its height was a matter of conjecture. The snow-mantled crags were said to be 6,500 feet high, but there was also a 5,000-foot pass that led through the mountains. Eckener poked Graf‘s snout toward the precipitous granite wall, probing for an opening, and finally found what he though was the mountain pass.

The pass began as a high mountain valley, but it soon turned into a steep-sided canyon. At 5,000 feet, the valley-canyon kept rising, forcing Graf to do the same. The airship climbed higher and higher, its vulnerable fabric belly only a few hundred feet from the sharp crags. Sheer canyon wall encroached as well, rising funnel-like to within 250 feet of the struggling dirigible.

At 6,000 feet, with Graf Zeppelin a bare 150 feet above the ground, the mountain chain abruptly fell away. They were through the barrier, and the azure Sea of Okhotsk beckoned beyond. Though he was never one for displays of emotion, Eckener threw out his arms and exulted, “Now that’s airship flying!”

After that harrowing experience, smokers among the passengers must have had an urge to light up — except all smoking was verboten as a fire risk aboard ship.

The lighter-than-air leviathan arrived in Tokyo, Japan, on Aug. 19, 1929. The voyagers were warmly received by the Japanese, although there was nearly a diplomatic incident when Graf sailed over the Imperial Palace, an action that was strictly taboo. The slight was forgiven, so Graf Zeppelin duly landed at Kasumiga-ura Naval Base with the aid of a 500-man Japanese ground crew.

The next few days were a whirl of teas, parades and celebrations as the Japanese vied with each other to do honor to the airship argonauts. Although outwardly gracious, Eckener was out of sorts; Japanese food did not agree with him, he had a boil and he was nearly suffocating in the August heat.

And when it was finally time to leave, the Japanese ground crew damaged one of the gondolas.

Repairs were effected at once, and Graf was soon on its way. However, 18 members of the Japanese ground crew were so ashamed that they pledged to commit suicide if the airship did not successfully complete its journey.

The Pacific crossing was largely uneventful.

Gossamer cloud wisps floated past Graf as it raced along at around 70 mph, their cottony fingers caressing her sleek sides. At one point, the Zeppelin took advantage of the south-side fringe of a typhoon, which boosted its speed to a temporary 98 mph.

But most of the time clouds obscured the view, and the trip was so smooth the passengers almost lapsed into boredom-induced comas.

On Aug. 25, Graf Zeppelin neared the California coast. The great airship’s visit to San Francisco could not have been more dramatic. Emerging from a cloud bank, late afternoon sunlight glinting off her silvery flanks, the airship made quite an impression.

No one could fail to recognize the huge dirigible, because the great red letters “Graf Zeppelin” were in clear view on the nose. Graf did not need to worry about colliding with the Golden Gate Bridge, because it was as yet unbuilt, but contrary winds forced the airship to enter San Francisco Bay at a crablike sideways angle.

After a few parade passes over San Francisco, much to the delight of Bay Area crowds, Graf headed south to Los Angeles.

When the dirigible moored at Mines Field, it had logged an official trans-Pacific flight time of 79 hours and 3 minutes.

But when the Zeppelin tried to take off in the early morning hours of Aug. 26, a temperature inversion layer held the airship down.

Years later such inversion layers would trap pollution and create smog, but now the Zeppelin was held fast by an invisible roof of warmer and less dense air, hovering just over a ground-hugging cold layer.

Crew members had to lighten ship, so surplus food, furniture and water ballast were unceremoniously dumped.

When takeoff was attempted, Graf rose, but unevenly, causing her tail and stabilizers to furrow the ground. The passenger gondola cleared some nearby power cables, but the dragging tail was on a collision course with them.

“Down elevator!” Eckener cried, and this maneuver lifted the tail enough to clear the cables.

The rest of the journey was more triumphal procession than routine trip. The route took Graf across Arizona and New Mexico, then northeast to Chicago before heading toward the Atlantic seaboard.

When Graf reached New York, it floated over the concrete canyons of Manhattan to the applause and delight of millions.

The American version of the world flight ended when Graf Zeppelin moored at Lakehurst on Aug. 29, 1929, establishing a speed record of 21 days, 7 hours and 34 minutes.

And if various layovers en route are subtracted and only flying time is counted, then the tally stood at 12 days and 11 minutes for circling the globe.

A gratified Eckener was given a ticker-tape parade in New York that rivaled Lindbergh’s two years earlier, and President Herbert Hoover lavishly praised the globe-trotting argonaut, comparing him to Columbus.

Eckener stayed in New York on business, so Graf Zeppelin completed the German version of the world circumnavigation under the command of Captain Ernst Lehmann. When Graf reached home base at Friedrichshafen on Sept. 4, the airship had officially logged 21,200 miles for the whole flight.

There was a comic footnote to the world cruise.

When Graf landed at Lakehurst on Aug. 29, Otto Hillig came forward with a writ of attachment.

Hillig was one of those passenger hopefuls who had been bumped before the flight began, even though he had paid his $9,000 up front. Furious at being left behind, Hillig was determined that the Zeppelin company was going to have to shell out.

A deputy arrived at Lakehurst to serve the writ, but Navy officials explained that to fulfill the letter of the law, the sheriff would have to remove Graf Zeppelin from its hangar. Undaunted, the lawman replied he was determined to seize the airship, even if it meant he would have to “tie it to a tree.”

Eventually, the Zeppelin company posted a $25,000 bond, and Graf was allowed to fly home to Germany. Hillig sued the Zeppelin company for $109,000 for his alleged “chagrin” at being left behind.

The matter was eventually settled out of court.

The epic around-the-world journey was only one facet of Graf Zeppelin‘s sparkling career.

The most successful commercial airship ever built, it was the first aircraft to fly more than 1 million miles; the official total was 1,060,000. A frequent visitor to North and South America, Graf crossed the Atlantic 144 times and carried some 13,000 passengers in a nine-year career.

Graf Zeppelin was honorably retired in 1937, the same year its sister ship, Hindenburg, caught fire while landing at Lakehurst, with a loss of 36 lives.

By then the Nazis were in power with a Luftwaffe chief, Herman Goring, who had hated airships even before the Hindenburg disaster. In 1940, on Goring’s express orders, Graf Zeppelin was dismantled and its metal used to build a radar tower in the Netherlands.

Graf Zeppelin is no more, but its memory still stands as a symbol of the all-too-brief airship era.

RELATED

This article was written by Eric Niderost and originally published in the July 1993 issue of Aviation History magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times. For more great articles, subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!