The strike was in its third week.

Picketers had plans to bombard non-striking colleagues at the front gate right at quitting time, 5:30 p.m. on Friday, June 13, 1941. But before that confrontation could be joined, the boss led loyalists off the company grounds to a nearby high school, where he held an impromptu meeting.

By the time 400 picketers, waving placards and signs, realized what was up and raced to the school, most of the scabs had left. Except for a handful of allies, only the boss himself remained, sitting in his car and tipping his hat at the strikers in the style of President Roosevelt.

Out of the crowd rushed the tall, steely-eyed strike leader.

Art Babbitt shouted at his boss and former pal, “Walt Disney, you ought to be ashamed of yourself!”

Disney scrambled from the vehicle, fists clenched, calling Babbitt a dirty sonofabitch. The crowd came between them, half booing, half cheering.

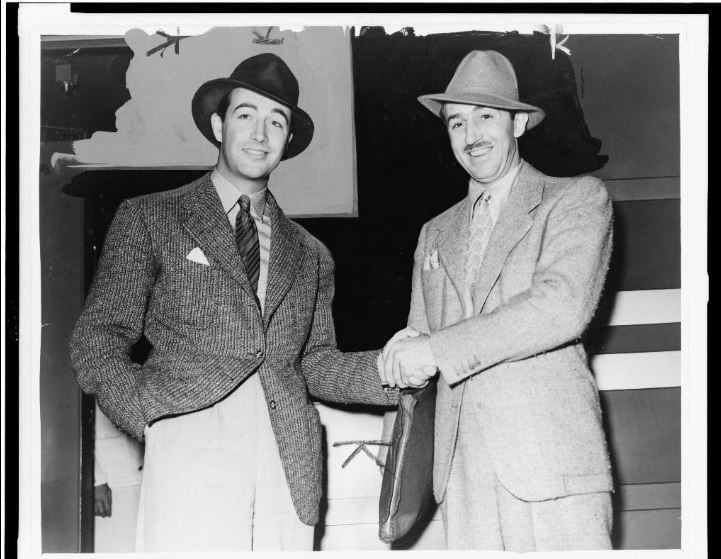

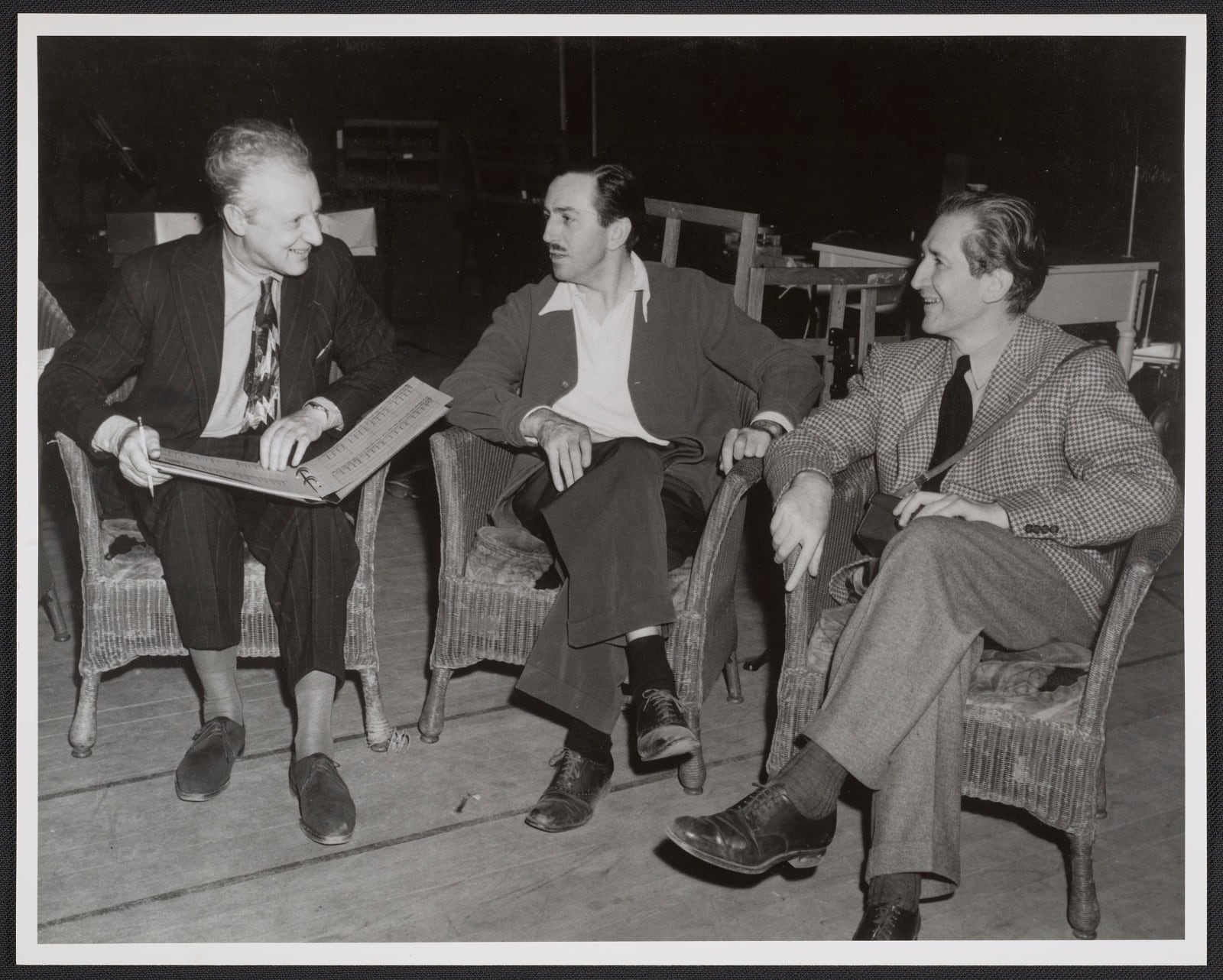

Before the 1941 strike at the Walt Disney Studios, Art Babbitt considered Walt Disney his friend. The men owed much to one other. Babbitt was unquestionably one of Disney’s star artists during the Golden Age of animation.

And Walt Disney once entrusted Art Babbitt with the brand and the characters he guarded so dearly. Babbitt developed Goofy’s movements and personality. He contributed Oscar-winning animation to The Three Little Pigs and The Country Cousin.

Walt had assigned the animator feature characters like the Queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Geppetto in Pinocchio.

Disney and Babbitt shared an ambition to elevate animation to fine art, and to that end Art helped Walt establish an in-house art school. Babbitt could claim to have been among the reasons Disney animation advanced exponentially between 1932 and 1941, Babbitt’s professional heyday.

But now these creative titans were at war, and the Disney Studios’ fate was at stake.

Strikes were nothing new. Capitalizing on half a century of labor activism and the desperate years of the Depression, enthusiasm for organizing had unionized the Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors assembly lines and a host of other industries — albeit not without resistance and even violence.

At first, unions enlisted assembly line workers and the manual trades, but now more and more creative types, like those in Hollywood, were standing together.

Across Hollywood, crafts had been unionizing through the 1930s. Actors, directors, writers, projectionists, electricians, musicians, background painters, secretaries, film processors—name any job in filmmaking, and it had a union, except for animators. And Disney Studios was the biggest employer of animators in Hollywood.

Walt Disney had grown up hearing all about labor and capital. His father, a socialist, often brought home brochure illustrations of the bloated capitalist and the woebegone worker for his artistic son to copy.

The elder Disney “thought everybody was as honest as he was; he got taken many times because of that,” Walt said in adulthood.

“I know the usual union methods. I’ve been brought up through my life with them. My dad was beat up by a bunch of union people one time.”

Walt, who as a volunteer drove an ambulance in France after the First World War’s armistice, had a strong streak of practicality and drive to succeed.

He was still a teenager in Missouri when he formed his first animation company, Laugh-O-Gram, which went bankrupt in 1923.

He and brother Roy next built Disney Brothers Studio. In 1927, Walt created the cartoon character Oswald the Rabbit for Universal Pictures and distributor Charles Mintz. By 1928, when Walt traveled to Mintz’s New York office to negotiate a payment increase from $2,250 per short, Mintz had hired away most of Walt’s employees and told Walt he would be getting $1,400 per animation and giving Mintz half the profits.

To escape the deal, Walt had to give up Oswald. He found himself with no contract, no character, and a bare-bones staff.

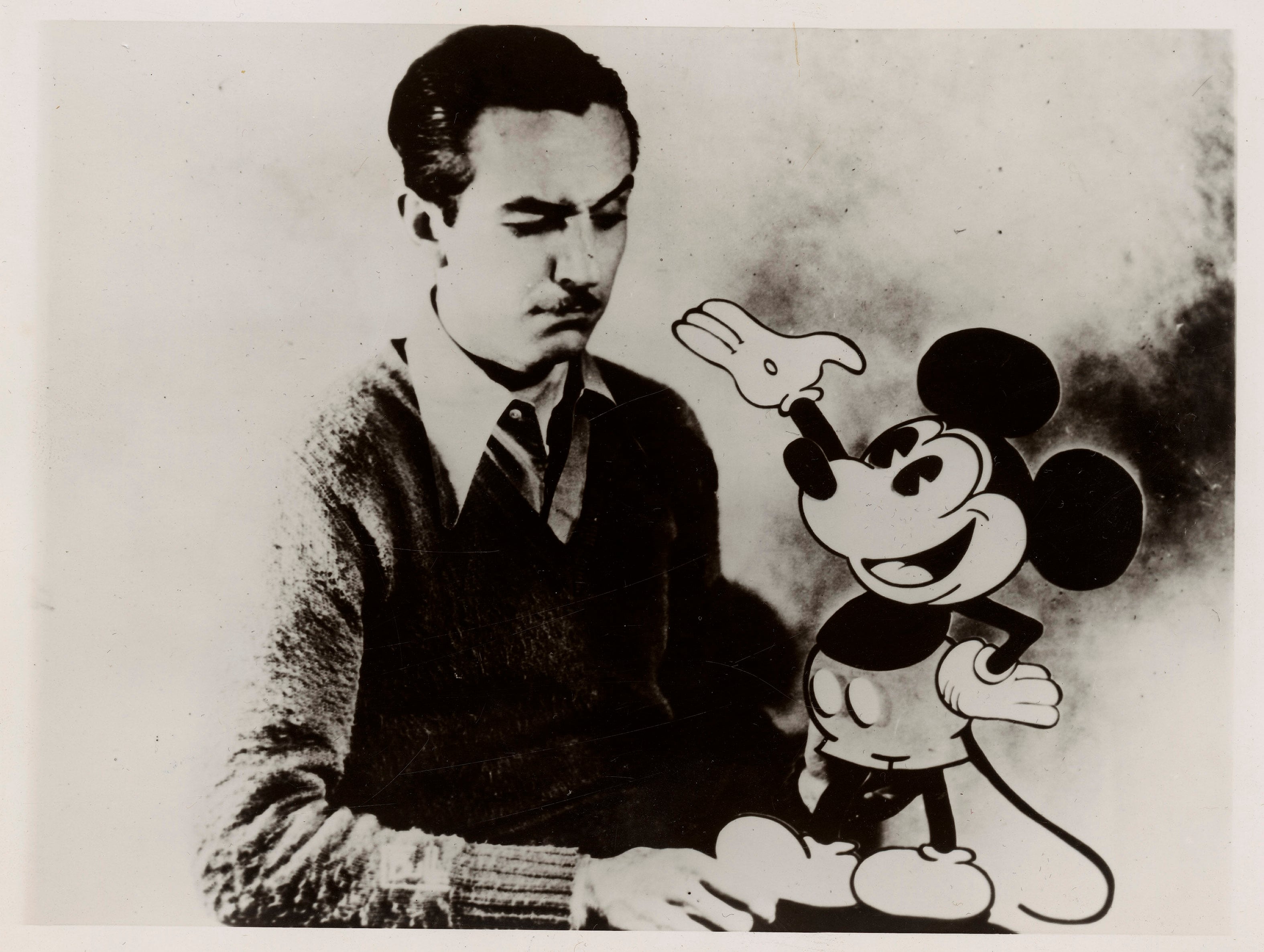

On the train back to Hollywood, Walt sketched the character that became the fabulously popular Mickey Mouse. Enriched by Mickey’s global stardom and remembering Oswald’s sad fate, Walt branded all his studio’s creations with the Disney moniker. Walt was the studio, and the studio was Walt.

Mickey Mouse was as huge a star as Clark Gable, but Clark Gable did not need a team of dozens in order to come alive. At Disney Studios, directors met with story men and storyboard artists to outline each cartoon short — and later, each full-length animated feature.

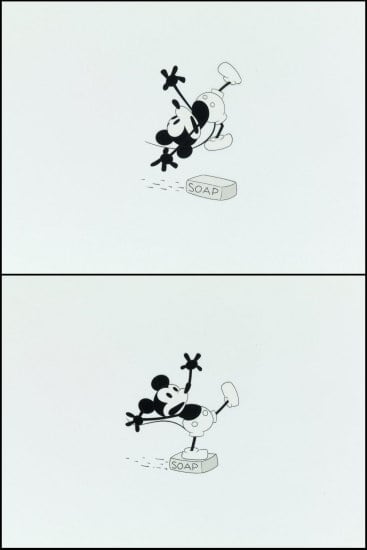

Like actors making performance choices, supervising animators planned each character’s actions. These artists’ drawings went to assistants who filled in the frames between main poses with additional drawings. Assistant animators handed their work to in-betweeners who completed necessary drawings.

Once an animation passed a camera test for exposure and smoothness of movement, a stack of pencil drawings went to inkers. The inkers traced the drawings onto sheets of transparent celluloid, giving the “cels” to painters for color.

Finally, one frame at a time, the production camera department shot a negative at a rate of 12 to 24 drawings per second. Each animation artist had a hand in bringing a cartoon star to the screen, and none belonged to a union.

The first try at organizing the artists at Disney arose because of racketeer Willie Bioff.

Bioff, a member of mobster Al Capone’s gang, was also the West Coast head of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, in 1937 Hollywood’s biggest, most corrupt union.

According to Variety, the show business trade magazine, it was “an open secret” that IATSE regularly made a practice of signing up entire departments at a studio, then threatening a strike there unless the studio’s management greased Bioff’s palm.

Art Babbitt, filled with creative ambition, had nothing against empowering the workingman. Born in 1907, Arthur Babitsky grew up in Sioux City, Iowa, a son of poor Russian immigrants. To help support his family, he went to New York at 16, struggling as a commercial artist until 1929, when he landed an animation job at TerryToons Studio, later famous for Mighty Mouse.

Babbitt animated for three years at TerryToons before applying to Disney — the only studio he saw as sharing his vision for animation’s future. A master at self-promotion, Babbitt hand-painted a letter on a sheet of paper 18 feet x 20 feet that he sent special delivery to Walt’s secretary.

The gimmick earned him an interview with Disney, who hired Babbitt in July 1932 at $40 a week.

By 1936, Babbitt was making $200 a week as one of Disney’s top artists, and was in the thick of the action. That year the studio was making Snow White, a project so daunting that Walt and Roy went on a hiring spree, muscling up the animation staff from 80-odd to around 1,200.

In late 1937, with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs about to premiere, Babbitt read in Time magazine about Bioff’s corrupt influence on the motion picture industry. He wondered how long Disney could fend off IATSE and the mob.

Babbitt conferred with Roy Disney, who sent him to Disney’s chief legal counsel, Gunther Lessing. Babbitt and Lessing outlined a “social organization,” the Federation of Screen Cartoonists, that Lessing said would serve their purposes. While Babbitt was arranging meetings and starting to draft a charter, Lessing encouraged him to enroll as many Disney employees as possible in the Federation.

Babbitt did not realize that the Federation was a “house union,” company-led and company-controlled. Babbitt just wanted to keep out Bioff. Lessing wanted to insulate Disney from all independent union activity.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered to ecstatic reviews, boffo box office returns, industry honors, and warm words from Disney.

“Dear Art,” Walt wrote, “since the critics have voted Snow White best picture of 1938, I thought you might like to stow away the attached copy of Film Daily with all the other memoirs you may be receiving for your grandchildren.”

Another of Babbitt’s keepsakes was a photo of the Snow White animation team.

Pending National Labor Relations Board certification, the Federation had to sit on its hands, frustrating Babbitt until July 22, 1939, when the NLRB declared the Federation the sole union for Disney employees.

Babbitt and the rest of the Federation’s negotiating committee scheduled a meeting with Roy Disney in October, hoping to negotiate a contract. Another goal was a small raise for inkers and painters, who at $18 and $16 a week were the lowest-paid in the industry.

Roy listened but shook his head, saying he “had no use for unions.”

With no contract, the Federation was powerless. The negotiating committee voted to let the hollow union die.

Deploying profits from Snow White and a loan from Bank of America, Walt spared no expense constructing a campus-style studio in Burbank, over the hills from Hollywood.

Intended to streamline the animation process, the new production house was rife with status symbols. Top artists enjoyed wall-to-wall carpeting; lesser animators got bare linoleum. Only those paid $100 a week or more could join the in-house exercise facility, “The Penthouse Club.”

Babbitt would not use the gym. Walt asked why.

“As soon as you make it open to everybody,” said Babbitt, “I’d be delighted to join.”

Animators elsewhere were forming or joining real unions. The Screen Cartoon — later “Cartoonists” — Guild was organizing animation artists around Hollywood.

By December 1940, the Guild had a contract with MGM, maker of the hit “Tom & Jerry” cartoons. MGM artists, especially the inkers, painters, in-betweeners, and assistants who occupied the lowest rungs of the production process, received raises. One by one, the Guild was signing up workers at all the animation studios, circling the biggest fish — Disney.

On Dec. 11, 1940, Walt and Lessing summoned Babbitt and the other four men who had been the moribund Federation’s original negotiating committee. Walt showed the artists a letter from the Guild claiming that the union represented a majority of Disney artists, and demanding that Walt sign a contract. He called on the five to reanimate the Federation, subvert the Guild, and “stop this thing.”

“You know how I am, boys,” Babbitt quoted Walt as saying. “If someone tells me to do something, I will do just the opposite, and if necessary I will close the studio.”

Babbitt saw the request to revive the Federation as hypocritical. If the point was to empower employees, why block a bona fide union? Lessing talked vaguely about a contract, but revealed nothing concrete. The Federation had been demanding a contract for a year and half without any result.

The negotiating committee members got together a week later to determine their next steps.

“I would have liked to have said to Walt, ‘Well, you’re the boss — whatever you say goes,’ and then I’d be a good boy,” Babbitt said at the Federation meeting. “But still at the same time, I feel I owe an obligation to all the people that have been foolish enough to follow me into this thing, and I can’t feel that it’s right.”

During that meeting, Babbitt expressed empathy for the man who had made him a prince of Hollywood animation.

“As swell as Walt has been in the past, he’s never taken the trouble to see the other side,” Babbitt told his colleagues. “He’s firmly convinced that all unions are stevedores and gangsters. It has never occurred to him that he might find a decent person to deal with. If Walt had taken the trouble to find out what we were doing and why we were doing it, the contract would have been signed long ago.”

Babbitt quit the Federation and began attending Guild meetings. By March, he was chairing the Disney unit of the Screen Cartoonists’ Guild, Local 852.

This infuriated Walt and Lessing. Lessing reactivated the Federation with replacement committee members and renewed force.

Disney had come off Snow White’s success to produce Pinocchio and Fantasia, both released in 1940. Each lost about $1 million because in September 1939, Europe went to war, slamming shut the international market.

To make his loan payments, Disney, now more than $3 million in debt, had to go public. When Walt and Roy asked Bank of America for more credit, the bank and Disney stockholders urgently suggested the company lay off personnel. Walt instead bore down on producing shorts, accelerating production and monitoring employee efficiency, which added to worker stress.

“In desperation I tried to keep these people employed by increasing their output,” Walt, on the verge of tears, recounted the following year. “I felt a responsibility to all these people. It was my mistake. I didn’t know it.” Some Disney employees empathized with the studio, others saw management as incompetent and top-heavy.

Walt doubted the company could survive the higher salaries that unionization would impose on Disney. On Feb.10 and 11, 1941, he addressed his entire staff in the studio theater.

“There are certain individuals who would like to blame the executives of this company for not foreseeing this calamity that was caused by the war in Europe,” Walt said, referring obliquely to Babbitt. “I think that is unfair…how the hell can anyone hold us responsible?”

Walt closed by declaring that the studio wouldn’t have to resort to drastic measures “if every one of you would dig in and do his individual and collective damnedest to roll out production of the highest quality with the most economy.”

The speech left the staff more polarized and drove many abstainers to sign with either the Guild or the Federation. Whichever collected a majority of Disney artists’ signatures would be the union at Disney, and the rival sides inundated the campus with fliers and petitions. In the halls, people were buttonholing one another to sign up.

More than once, management demanded Babbitt shut down Guild recruitment at the studio.

“People on both sides are guilty,” Babbitt responded. “Everyone who is not on my side is bound to criticize me!”

Walt cornered Babbitt in a hallway.

“You don’t know what is going on in the rest of the studio,” Walt said, according to Babbitt in 1942 testimony. “If you don’t stop organizing my employees, I’m going to throw you right the hell out of the front gate!”

The simmer came to a boil May 16, when Disney laid off 24 Guild members, several of them committee chairmen.

The Guild demanded Walt sit down with the union or face a strike. Walt refused. On Tuesday, May 27, 1941, the company abruptly fired Babbitt. Armed guards escorted him off the lot.

That night the Guild unit voted to strike, and in the morning, more than 300 Disney artists were marching at the gates demanding that Disney recognize the Guild.

The strikers picketed 24 hours a day, carrying signs illustrated with Disney characters. Across from the studio, an outdoor cafeteria sponsored by sympathizers served three meals daily. Striking artists drew sketches distributed to the press. Teams of pickets rushed any theater screening a Disney picture.

Other unions, including the Screen Actors Guild, lent support.

Developers at Technicolor refused to process Disney film.

Newspapers withheld Disney comic strips. RKO, which distributed Disney films, announced it would stall all Disney releases until the strike was settled.

Union animators at Warner Bros., after ending shifts animating Bugs Bunny and other Looney Tunes characters, built parade floats and effigies they displayed in step with the Disney strikers. Dances, magic shows, fairs, and other benefits filled Buena Vista Street at night. Trade papers like Variety and the Hollywood Reporter, as well as publications across the spectrum, covered the strike in detail.

“We represent a majority of the cartoonists in the studio,” Babbitt told the Daily Worker. “We demand recognition of our field and a closed-shop contract. We demand wage adjustments and the betterment of working conditions. We want all bonuses previously promised but not paid; we want to get the company men off our necks every time we turn around.”

Walt Disney doubted the Guild actually had the enrollment that the union claimed. He met regularly with Guild members, trying to determine the true numbers. The Guild wanted to crosscheck union enrollment against Disney’s payroll.

Walt refused, saying he would accept only the results of a secret-ballot vote deciding which union would represent his people. Both sides accused the other of coercion.

The Guild had enough support among unions to make a credible threat to place Disney and all its productions on a “do not patronize” list unless Walt agreed to a crosscheck.

“I have never been a coward,” Walt replied. “When it comes to a compromise of this sort, to me it isn’t a compromise. It’s just laying down. To me it’s one of the most un-American things that can be done.”

As the stalemate ground into a ninth week, strikers were edging closer to poverty. Nonetheless, violence never intruded.

On July 28, two NLRB mediators finally arrived from Washington, DC. The mediators’ Aug. 2 ruling found in favor of the strikers. The studio would sign a closed-shop union contract with the Guild; wages would rise 25 percent to the industry’s peak; should the company propose layoffs, an independent joint committee would review them; each striker would get 100 hours in back pay.

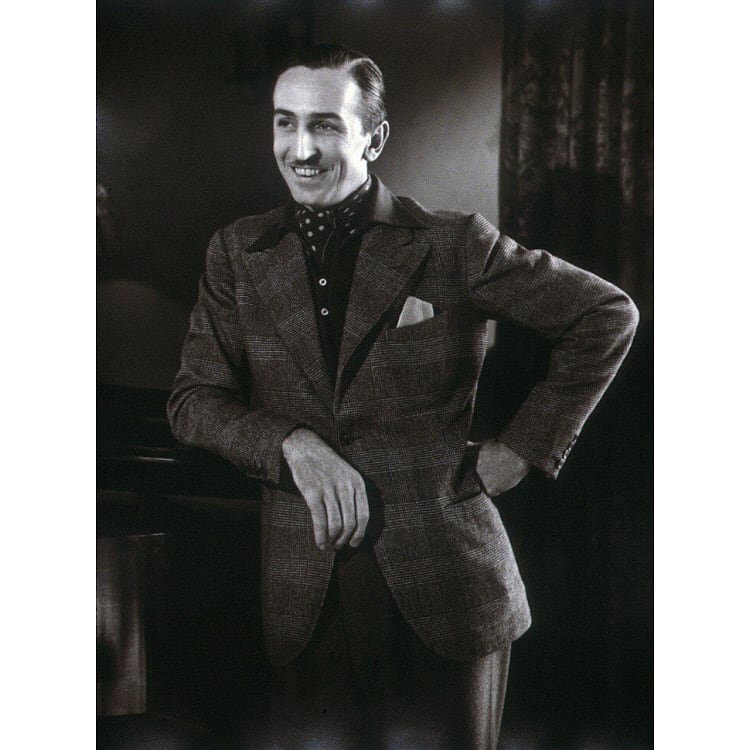

The artists returned to work, but the studio was never the same. Walt, who valued loyalty above all, withdrew from the family unit he had created. Disney’s own involvement with his studio would be increasingly managerial, and never again would he experiment with animation the way he once had.

The Golden Age of Disney animation had ended.

Back at the studio, Babbitt found himself short of assignments. On Nov. 24, the company laid off its former star animator, ostensibly for lack of work.

He and the union sued Walt Disney, and in October 1942, Babbitt appeared in court, offering testimony that clashed with representations by Walt, Gunther Lessing, and every director the animator ever worked with at Walt Disney Studios.

The proceedings lasted seven days; Babbitt and the Guild won.

Though he was reinstated in his job, Babbitt immediately enlisted in the Marines. He served three years in intelligence in the Pacific, mustering out in October 1945 as a master technical sergeant.

At Disney, which had grudgingly held his position for him, Babbitt was persona non grata. No non-striker, other than directors, dared to talk with him or even look his way.

On Jan. 16, 1947, Babbitt quit.

He went on to success at United Productions of America with Mr. Magoo and other UPA cartoons, and won dozens of awards for commercials.

Still, nothing in post-strike, post-war life matched what Art Babbitt had achieved in his heyday at Disney. He was directing ads for Hanna Barbera in 1973 when Canadian animator Richard Williams rediscovered him. Williams, a connoisseur of classic animation, hired Babbitt to teach at his production house in London.

Babbitt’s years of direct influence inspired Williams’s hand in Robert Zemeckis’s 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit, a masterful blend of live action and animation that helped propel the big-screen renaissance in animation that continues today.

In 2007, 15 years after Babbitt died, Walt’s nephew, Roy E. Disney, inducted Babbitt into the company’s creative pantheon by honoring him as a Disney Legend. Roy noted that right up until his death, Babbitt kept the photo of the Snow White animation team, carefully labeling each person.

By his own face, Babbitt had written “the Troublemaker.”

This story first appeared on HistoryNet.com, a sister publication of Navy Times.