With a lethal Hurricane Dorian trundling toward the eastern seaboard last week, the Navy sortied its warships and aircraft, ordered mandatory evacuations for personnel in coastal areas and also sent to safety its sea mammal sentries.

Officials told Navy Times on Tuesday that they brought their specially trained bottlenose dolphins and sea lions from Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic in Kings Bay, Georgia, to shelter in the Florida panhandle’s Naval Surface Warfare Center Panama City Division.

It marked the third sea mammal evacuation to Panama City since 2016, when Hurricane Matthew menaced the East Coast. The Navy moved the creatures for Hurricane Irma in 2017, too.

“At NSWC PCD, we personally understand the trials and tribulations that come with the devastation of a hurricane, especially after Hurricane Michael severely impacted our area in 2018,” said Nicole Waters, the Florida base’s fabrication and prototype shops project manager, in a prepared statement emailed to Navy Times.

“We strongly support the ‘One Team, One Fight’ initiative and will always be willing to help protect any Navy personnel and assets.”

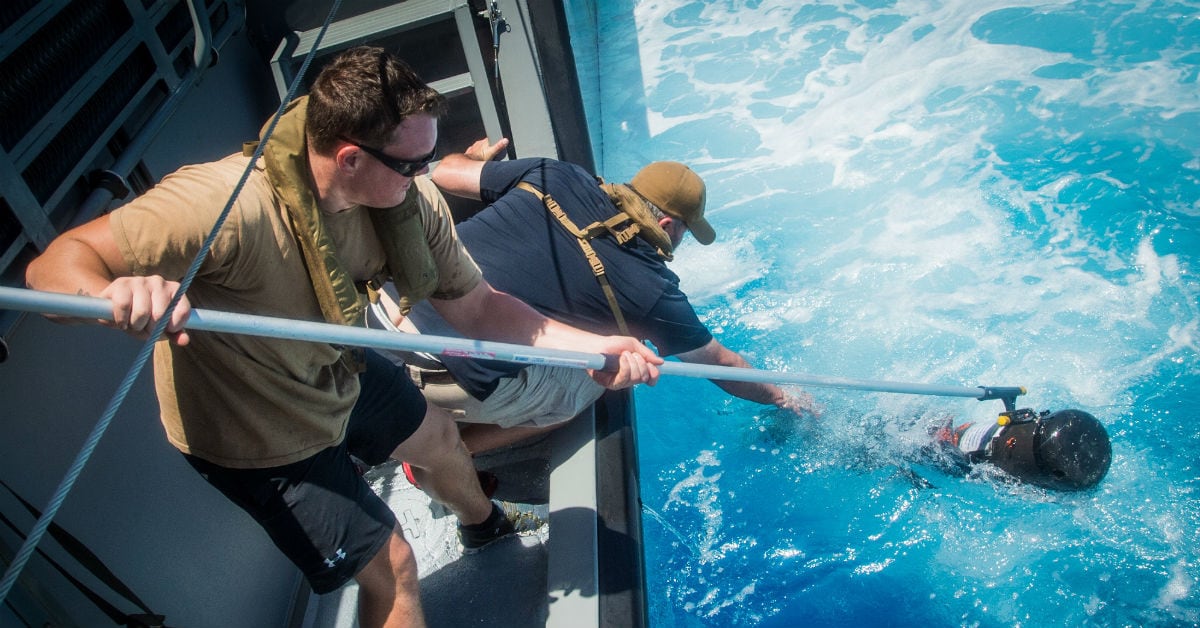

In Kings Bay, the sea lions and dolphins patrol for enemy frogmen, underwater robots or other suspicious activity in the waters near the strategic ballistic missile submarines.

In the past, they’ve also been used to hunt mines and other potential hazards to warships.

On the West Coast, a similar stable of Navy creatures conscripted for the Swimmer Interdiction Security System guards Puget Sound’s nuclear boats.

“The dolphins’ own biological sonar can detect any type of underwater intruder in murky water. The sea lions are able to efficiently interdict an underwater intruder," added Mark Patefield, a biological technician from San Diego’s Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific, in the statement.

While in Florida, however, the roughly two dozen mammals didn’t run operations or conduct training.

Naval Surface Warfare Center Panama City Division spokeswoman Ashley Conner told Navy Times that the sea lions were kept in pens on the pier and workers made open water pens on a dock slip for the dolphins.

“From an NSWC PCD perspective no training was impacted,” she added.

RELATED

The last of the sea mammals left Panama City on Sunday. But citing potential operations security concerns, Conner said she couldn’t disclose when they arrived in Florida.

Navy Times tried to get information about how many animals arrived at her base, how they were transported there, where they are now and what seemed like other routine questions, but officials declined to answer them.

Mark J. Xitco Jr. — the director of the Navy Marine Mammal Program in San Diego — said by email that “most of the questions you posed are not answerable due to OPSEC.”

That didn’t surprise Michele Bolo, a California-based animal activist who filmed XItco’s Point Loma operations from the Harbor Drive Pedestrian Bridge in 2016 and 2017, surveillance that helped spark a CBS News 8 exposé into allegations of sea mammal mistreatment there.

She told Navy Times that researchers trying to probe the military’s program routinely are denied documents by officials who claim they’re classified records.

She pointed to “hundreds of suspicious death" of the animals over the past three decades, including drownings, that the public can’t scrutinize.

“They’re still secretive about everything,” Bolo said. “If you want even basic information, you’re going to have to go down a long road to get it.”

And along the way, she said, the public is going to discover that the Navy thinks of their “dolphins and sea lions as their back up plan” in case a new generation of underwater robots fails to work.

RELATED

Critics have long decried the Navy’s sea mammal program as an expensive Cold War throwback with aging animals and mounting costs tied to their transportation and veterinary care.

For the past five years, however, contractors have focused on delivering new high tech tools to the Navy that can replace some of the chores currently performed by animals, including Unmanned Underwater Vehicles such as the Bluefin-21 deep sea submersible and bomb-zapping Knifefish drones.

The Center for the Study of the Drone at New York’s Bard College estimates that last fiscal year’s budget earmarked $47.5 million for three Navy Knifefish UUVs, plus $16.7 million on research and development costs for the system and $12.1 million for an Unmanned Influence Sweep System for surface mine searching.

The sea service also allocated $88 million for 19 MK-18 MOD-1 Swordfish UUVs, nine MK-18 MOD 2 Kingfish UUVs, nine remote-operated vehicles, plus other gadgets designed to defeat mines or track suspicious activity in the water, like Autonomous Underwater Vehicles.

But Bolo said technological glitches and program delays have dogged the new systems, forcing the Navy to continue to rely on sea mammals for some duties.

As for the evacuation before Dorian arrived, she said federal law mandates that the Navy have a plan for moving the animals.

In his prepared statement, Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific’s Patefield had a different take.

“We have a very high success rate with these animals. Our goal and purpose is that these animals get the best care possible,” he said.

“This is a perfect example of that — including the personnel and teammates that come together like a family. We have a lot of good people who are supporting these animals in the best way possible.”